|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By STEPHEN BEAVEN

Photographs by Judy Lutz Spencer

'It's in your blood'

Migrant labor is dirty-hands work. But year

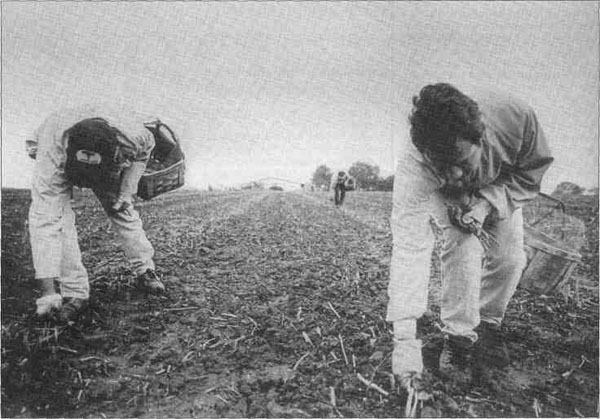

after year, generation after generation, they come back to pick our fruit and vegetables 10/August 1995/Illinois Issues The rain starts long before dawn, about the time the trains rumble across the tracks at the edge of Princeville's migrant camp. It continues, off and on, as workers begin to stir in the dark. Some have already left when Gerardo Garza drives out about 5 a.m. with his father Audaz in the passenger seat. Gerardo whips his sturdy red Aerostar van through tiny, sleeping towns northwest of Peoria at speeds that would turn a traffic cop's head. He's in a hurry. The first dull light of day is creeping up, and the Garzas have work to do. It's late May, cold and wet, not exactly a perfect day to pick asparagus. But the Garzas lead crews of migrant workers for the Princeville Canning Co., and there's little time to waste during picking season. So, despite the weather and the poor yield this year, about 90 Hispanic migrants will strap baskets to their waists and snap sodden asparagus stalks off at ground level for up to 17 cents a pound. This is migrant work, the sort of job nobody else seems to want. Candy asses don't do this kind of work. It doesn't fit neatly into a little 9-to-5 box, with a 401K, health insurance and overtime. But the Garzas and their crews are part of a working subculture in Illinois, one that's often tucked into small towns like Princeville or in isolated rural areas. Every year, about 66,000 migrant workers and their families stream into the state to pick fruit and vegetables, detassel corn and work in nurseries and canneries. Many of them drive more than 1,000 miles from Texas to work for most of the year and then return home. They endure long work days, often substandard housing and poverty-level pay. There are no company benefit packages. Though Capitol Hill budget-cutters have targeted federal programs migrants count on, Gerardo Garza figures his annual pilgrimage will continue. He first arrived in Princeville when he was 15 days old. Now he's 38, a third-generation migrant. In August, after Audaz retires, Gerardo will inherit his father's job as the camp supervisor, while continuing as a recruiter and crew leader. Though there will be no asparagus crop, he will return to Princeville next year with his wife, Maria Teresa, and their three children. They'll set up house and start working again. "You get used to it," he says one day in the kitchen of the tiny cabin he shares with his family. "It's in your blood. You keep coming back and coming back. We're like the geese. We follow the good weather." Since the Civil War era, one group of migrants after another has worked its way through Illinois. First came the freed slaves, who toiled in Alexander, Pulaski and other southern counties while on their way to the big cities, according to Nancy Tegtmeier, director of the Illinois Farm Worker Ministry for the Illinois Conference of Churches. Near the turn of the century, whites from Appalachia moved in. Then, about 50 years ago, when whites began taking better jobs in coal mining and other industries, Hispanic workers took the migrant jobs.

A lifestyle built around "Everything was new for me," Audaz says. He's sitting in his office, wearing a baseball cap that reads "Retirement: No clock. No phone. No money. No worries." His face is long and lined and he wears thick glasses. "It was a different country for me in a way because it was so far from Texas. I liked it. I was young." He's returned every year since. Like all migrants, his lifestyle is built around labor. He works for six or seven months in Illinois and takes the rest of the year off in Texas and collects unemployment. His fellow travelers do the same or work and take their pay in cash. Migrant living isn't easy, though. Sometimes the work is good and the housing is humane. Sometimes migrants are crammed into crumbling shacks and trailers and make the same as a high school kid delivering pizzas. Migrants on the West Coast are generally better off than their colleagues, says Susan Bauer, health resources coordinator for the Community Health Partnership, which serves migrants in Illinois. There's more stability on the West Coast because the work is year-round and there's a history of farm labor organization. Migrants have organized in California, Washington state, Ohio and parts of Florida. Migrant work on the East Coast is the worst, Bauer says, with more substandard housing and labor violations. Illinois, apparently, falls somewhere in the middle. Although there were efforts to organize in the late '80s, migrants don't work under contract in Illinois. "I don't think they're the best ones," Audaz says of the camps in Illinois, "but I don't think they're the worst, either. I call them fair." Migrant work is spread throughout the state, from Cobden to Kankakee and Havana to Hoopeston. There is a big migrant work force in the collar counties, especially in the booming nursery industry, Bauer says. Seasonal work schedules vary. The mushroom industry is year-round. The nurseries start in February or March and continue through Christmas tree season. Fruit and vegetable work starts in April and May and continues through November. Bauer and Vincent Beckman, director of the Illinois Migrant Legal Assistance Project, agree that living and working conditions have improved somewhat in the past decade or so. Bauer attributes the improvement to pressure on the Illinois Department of Public Health and to the department's response.

August 1995/Illinois Issues/11

Public Health licenses and inspects about 55 migrant labor camps each year, says Pat Metz of the department's office of health protection. Sometimes inspectors come back with horror stories. One case involved a house in Joliet in which 24 to 30 people were living with only one toilet, with sewage flowing from the first floor to the basement and accumulating, according to a report based on three inspections. There were also holes in the walls and 15 refrigerators in the kitchen, in a hallway and on a porch. The workers were employed by Neumann's Nursery, which was fined $800 in 1991. The last time the department inspected the site, in late 1993, the house had been demolished, its foundation covered with dirt. Though that's an extreme case, there are plenty of other instances of poor housing, say Bauer and Beckman. In recent years, there's been more unaccompanied men coming into Illinois, looking for work, according to Bauer. They are more likely to live in ramshackle housing and endure poor working conditions, she says. Beckman's office handles disputes about the terms of work and cases in which migrants haven't been paid. A 1991 study by the Illinois Migrant Council showed that migrants in Kankakee County made between $4 and $7 an hour. The average was $4.62. The minimum wage at the time was $4.25. Most of the workers surveyed said they did not receive overtime pay. At the Princeville Canning Co., there are 36 year-round employees and about 180 to 190 during the harvest and canning seasons, according to Dave Stoner, the plant manager. The pay ranges from about $4.80 an hour to $10 an hour, depending on the job. Many of the migrants work in the plant itself, especially after the picking season ends in mid-June. Rent is $4 a week, and the workers are paid a travel stipend of $50 each for the trip from Texas. About 80 percent of the migrants are U.S. citizens and the rest are legal aliens, Stoner estimates. The company started in 1925. It has employed migrant workers since 1948, Stoner says. He is quick to praise their work ethic and says he'd rather have migrants than locals any day. "We prefer to have migrant workers over local people simply because of the stability of it," he says. "They drive halfway across the country to work and, by golly, they work. The guy who lives down the street isn't as committed." Migrants could be affected by efforts to slash the federal budget. The U.S. House of Representatives has already passed welfare reforms that would bar some legal immigrants from receiving Supplemental Security Income, food stamps, Aid to Families with Dependent Children and non-emergency Medicaid when they're not working. A similar bill passed by the Senate finance committee would bar only Supplemental Security Income. But debate in the Senate has been fierce, and additional programs are targeted in other proposals, some of which would bar benefits even to newly minted U.S. citizens. In his kitchen, Gerardo Garza makes a point: He and his co-workers aren't suffering. Some have nice homes in Texas. Many have good transportation and work for only part of the year. But the work they do is hard and so is the travel, he says. "When it rains," he says of the potential cuts, "it's not the same to be inside looking out as it is being outside looking in."

A society within a society

The initial impression, of course, is a shallow one. The camp is more than a collection of white huts with flaking paint. It's a village unto itself, with a culture and language of its own, a society within a society. Most of the workers are longtime neighbors. Many return to Princeville every year for decades, one generation following another. The cabins face inward from the road. Some workers have added homey touches, like gardens, to personalize their cabins. Inside, there are stoves, refrigerators, microwave ovens, televisions. Parked in front of many of the cabins are the huge, muscular trucks and vans migrants depend on to get them from their winter homes to work each year. Playground equipment sits behind the first row of cabins, and someone has put up a volleyball net. There's also a pavilion. But it's not a nightly gathering spot. There's too much work to do. Most migrants in Princeville come from either Eagle Pass or Del Rio, Texas, two border towns in the southwest part of the state. They're recruited in late winter and head north for the 1,300-mile drive in April. And though Princeville (population 1,421) is a second home, migrant life revolves around the camp and the canning company, not the town. There are no traces of Hispanic culture in Princeville outside the camp, despite the fact that for more than half the year more than 10 percent of its population is composed of Hispanics from Texas. Most folks in the camp and in town agree that everyone gets along. But other than at the school, there's little social interaction between Princeville natives and the migrants. The workers lead a separate, but not necessarily equal, lifestyle. "Hanging out in town a lot?" Gerardo Garza asks rhetorically. "No. It's just shop and come back." Of course, it took awhile for the town to get used to the workers, and vice versa. Though there may be a comfortable familiarity now when migrants return to Illinois each spring, the cultures have clashed in the past. Elva DeLuna is a 30-year-old education coordinator at the Seven Oaks Child Development Center. She has been a migrant all her life and remembers slights at other camps when she was a child. In more than one town, she remembers the migrant kids being rounded up before school, taken to locker rooms, checked for lice and given showers. "I always grew up thinking, 'Do they think Hispanics have never heard of a shower before?'" Gerardo and Elva have endured doubts about their future as migrants. Gerardo quit for a few years, worked a regular job in Peoria and then returned more committed to migrant work than ever after he became disillusioned with a 9-to-5 lifestyle. 12/August 1995/Illinois Issues

Elva, whose father is also a crew leader, continues to struggle with the travel each year. "It's pretty stressful," she says one afternoon, sitting in her second-floor office at the day-care center. "It's getting to me, the constant moving. You're really not settled anywhere. I'm 30 years old. I was born in Texas. I've never spent a summer in Texas. I only know from other people what it's like. It's like you're not from anywhere, even if the paper says you were born in a particular place. Mine says I was born in Texas. But I don't feel like I was born there." Gerardo is a born-again Christian who wears White Sox caps and has a self-deprecating sense of humor. In his kitchen, where water boils on the stove for dishwashing, he brings out two pictures. One shows him in 1975, holding a beer and a cigarette, wearing sunglasses and with hair down to his shoulders. The other is a picture of him at his office in Cambria, Wis., where he's worked for about 10 years as a crew leader. In that picture, taken two years ago, he is clean-cut, sitting at his desk like an office manager. Between those times, he tried to make a life for himself outside the migrant camps. From 1978 to 1981, he worked at an assembly plant in Peoria and lived in a trailer park near Bradley University. He had good health benefits and the pay was fine, but he got laid off too much and he didn't like Peoria winters. So, he moved to Texas and got a regular job at a concrete plant. In 1984, Audaz offered him a job in Cambria. He worked there until last year. This is the first year in nearly 20 years he's stayed in Princeville after the asparagus harvest. But he's glad to be back. He's with his family, and he's at home. At night, when the work is finished and the light gets dusky, it's easy to see why some migrants return even after they've retired from the cannery. In many ways, it's like a vacation campground, albeit one in which the campers return each year for months instead of weeks. It is truly an extended family, a close community with brothers, sisters, mothers, fathers, cousins, aunts and uncles. Before bedtime, which is early, the kids run themselves ragged, burning off preadolescent energy until they're exhausted. Some of the adults crowd the bathroom facilities, carrying towels, shampoo and toothbrushes. The darker it gets, the more quiet the camp grows. Tomorrow is a work day. But not everyone is preparing for sleep. One young couple walks around for most of the evening, holding hands. Later, on a small porch, they kiss in the dim light.

Generation to generation

On this cold, wet day in May, Maria Teresa and Sandra, Gerardo's sister, ride along in the van. They will run the scales that weigh the asparagus. On the way to the fields, Gerardo and Audaz talk about the rain, wondering if bringing the workers

August 1995/Illinois Issues/13

Audaz and Gerardo stand together, not touching, in the middle of the field for a picture. Generation II and Generation III. They wear boots, caps and work clothes and don't appear at all comfortable with the attention. But here they are, 38 years after Audaz brought Gerardo to Princeville at barely two weeks old so Audaz could go to work. And soon Audaz will hand over his legacy to Gerardo, his only son, keeping it in the family. Some day, Gerardo may be joined by his own son, Isai, on a pre-dawn drive to work. Suddenly, it doesn't seem so strange to see Audaz and his boy standing side by side on this cold morning, while most of the state sleeps around them. * Stephen Beaven is a staff writer for the Indianapolis Business Journal. 14/August 1995/Illinois Issues |

|

|