|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Shirley J. Portwood, When William T. Scott, a free African-American from Newark, Ohio, moved to Cairo in 1863, it was a small river city. Cairo was located at the southern tip of the free state of Illinois and bordered two slave states—Missouri across the Mississippi River to the west and Kentucky across the Ohio River to the south. By 1865 the city had grown substantially due to a large Civil War-era migration. Cairo had a total population of 8,569, of which 2,083 were blacks. The newly constructed Illinois Central Railroad ran through the city carrying passengers and freight north to Chicago, Rockford, Galena, and many stations along the way. Many northern cities and some rural areas along this and other railroad lines saw their black populations grow due to the transportation, jobs, and land offered by the railroads. There were numerous restaurants, saloons, and other small businesses in Cairo.

African-Americans may also have been attracted to Cairo by the numerous small industries such as stave and barrel manufacturers and sawmills located in the city. A man could make $1.00 to $1.20 for a ten- to twelve-hour day, a reasonably good wage for the time. Blacks did not know, however, that racism would hamper their opportunities for employment at these businesses. Women rarely worked outside their own households, but those who did earned $2.00 to $3.00 a week as domestic servants or washerwomen. Skilled laborers, almost all white men, earned $1.50 to $2.00 daily. Black skilled workers often abandoned their trades because whites refused to hire them and because increasing industrialization reduced the need for skilled laborers. William T. Scott, a barber who joined the United States Navy about 1860, moved to Cairo in order to serve aboard the Victoria. Scott remained in the city for nearly forty years, until about 1900. He and his wife Nellie had a son, William E. The senior Scott was a very active member of the community, participating in numerous social and political activities. Scott was also an entrepreneur who ran assorted businesses, including a saloon, restaurant, and billiard hall, and later a real estate office and detective agency. He reported in the 1870 census that he owned $1,300 in real estate and $2,000 in personal property—a substantial sum. About 1881 Scott became the editor and publisher of the Cairo Gazette, one of the first African-American newspapers in the state of Illinois. The Gazette may have been the first African-American daily newspaper in the United States. Scott witnessed many changes in Cairo during his nearly four decades there. When he first arrived, blacks had few rights in the state of Illinois as the state's Black Codes placed restrictions upon African-Americans, both slave and free. Black Codes had originated in the South, the homeland of most Cairo whites, and had been brought North by

13

southern migrants. The Illinois Black Codes required African-Americans to deposit a $1,000 bond with the county clerk as a condition of entering the state. This was an extremely large sum, much more than most people—black or white—could have afforded at that time. In fact, the bond was a way to discourage African-Americans from entering the state. Illinois blacks could not vote, serve in the state militia, or gather in large numbers. Blacks could be whipped for offenses for which whites would merely be fined. Although African-American property owners paid taxes on their real estate, and these taxes helped to finance the public schools, blacks could not attend them. African-Americans who received formal education went to private schools, usually run by black organizations such as churches or benevolent and fraternal societies. William Scott and other African-Americans in Illinois gained some rights in 1865 when the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution freed the slaves. That same year the Illinois General Assembly rescinded the Black Codes. Legislation in 1870 and 1872 gave blacks the right to attend public schools and outlawed segregated education in state-supported schools. Despite those laws, African-Americans and white Americans attended separate schools in Cairo and in most schools south of Springfield. Public schools in Cairo and extreme southern Illinois remained segregated for nearly one hundred years more, until the 1960s. Other legislation gave blacks additional rights—for example, access to public transportation such as trains—but these laws were often unenforced, especially in southern Illinois. In Cairo and southern Illinois, the largely southern white populace, like their brethren who remained in the South, established segregated facilities. African-American men gained the right to vote in1870. African-American women were granted suffrage, along with white women, when the Nineteenth Amendment took effect in 1920. Although their position improved in the Reconstruction and post-Reconstruction era, African-Americans were not given all the rights and privileges of their white counterparts. African-Americans were often denied jobs except as low-paying, low-status day laborers, dock workers, and railroad hands for men, and as domestics and washerwomen for women. Though Cairo's numerous small industries required a fairly large work force, white owners and managers rarely hired blacks in the better paying positions. Even the ranks of common factory laborer contained a smaller proportion of blacks than whites. Many white-owned businesses refused to provide service to blacks. City officials barred blacks from access to the publicly funded Cairo Public Library. Sometimes whites verbally

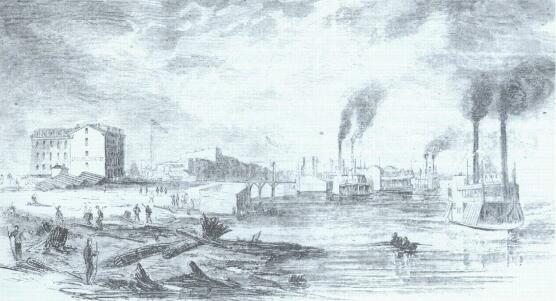

The Ohio River Levee at Cairo 14

Cairo, Illinois, and its vicinity, looking south from the St. Charles Hotel abused, harassed, or even physically assaulted blacks. William Scott, along with many African Americans in Cairo and throughout the nation, objected to the unfair way in which blacks were treated. Sometimes they met in private homes or businesses in order to discuss plans to gain equal rights. Scott hosted many political meetings within the black community. Walker Wilkerson, a wealthy Cairo black, periodically invited fellow African-Americans to meet at his hotel. Wilkerson also owned Wilkerson's Opera House and Wilkerson's Theater, as well as town lots and a farm. After obtaining the franchise, African-Americans began to run for public office. Their considerable voting strength and their strong community organization, as well as growing support from whites, enabled blacks to win a number of political offices in Cairo and Alexander County and other places in Illinois. Black entrepreneurs, whose own economic success was primarily dependent upon other black people, were leaders in the African-American community of Cairo. Their economic autonomy from whites made it possible for them to pursue their own political goals and to engage in political advocacy for blacks with little fear of the economic retaliation that sometimes restrained those who worked for whites. Many who had moved to Cairo during the Civil War left it, and the city experienced a decline in its popluation. The 1870 United States census recorded a decline in population from 8,569 (of which 2,083 were black) in 1865 to 6,267 (of which 1,849 were black). Yet Cairo experienced a large migration once again in the last three decades of the nineteenth century. By 1880 there were 9,011 residents in the city, of which 3,349 were African-Americans; in 1890 there were 10,324 residents, with 3,689 blacks. In 1900 African-Americans numbered 5,000 of 12,566. John J. Bird from Ohio was one of the first blacks to be elected to public office in Cairo. Bird and his wife Annie had lived in Canada for several years where their two sons, John William and Egbert, were born. In 1873 Bird was elected to a four-year term as police magistrate, a municipal judgeship. He was reelected in 1877 but resigned in 1879 before his second term was completed. Meanwhile, in 1873 Governor John L. Beveridge had appointed Bird to the board of trustees of the newly established Illinois Industrial Institute at Champaign, later renamed the University of Illinois. Bird was appointed to a second board term, but he resigned in 1882 before it ended. Perhaps the expense and inconvenience of traveling to Champaign for board meetings contributed to his decision. Bird served as co-editor of the Cairo Gazette with William Scott during the 1880s. Other African-Americans held elected and appointed offices in Cairo. Several served as assemblyman on the fourteen-member Cairo city council. From 1895 to 1897 Richard Taylor, Jacob Amos, and George Meridian simultaneously held assemblyman posts. Taylor, who ran various small businesses in Cairo, was an outspoken man who sometimes criticized city government. For example, during an 1897 meeting, he pointed out that African-

15

Americans were not permitted to use the city library, even though it was supported by public funds totaling $1,000 to $2,000 annually. Taylor voted against the library appropriations for that year in protest. Jacob Amos, an engineer at the city power plant, was more restrained in city council meetings than Taylor, but he expressed his disagreement with politicians in the black press. He wrote a series of letters to the Springfield Illinois Record during 1898. Amos charged that Republican leaders in southern Illinois were abandoning their party's more equalitarian ideals of an earlier era. These new policies had led to a decrease in the number of blacks in publicly funded jobs, a decline in African-Americans working on trains, and other decisions which had been detrimental to blacks, according to Amos. John W. Stepp was elected to a four-year term as Alexander County coroner in 1896. He was the first African-American to hold a county-wide position. Four years later, when he sought reelection, he was defeated by a very narrow margin. Blacks were elected to other offices, including constable and justice of the peace. Blacks also were appointed to the Cairo municipal police force, while still others held public jobs, as for example John Gladney, who did hauling for the city in the 1870s. Some African-Americans, including William Scott, ran unsuccessfully for public offices. Scott stood for Cairo city marshall in 1871 and for alderman in 1896. John Gladney in 1888 and Alexander A. Martin in 1892 were defeated for county coroner. Despite these and other losses, African-Americans continued to pursue public office. Scott witnessed other important changes in Cairo in the years 1863 to 1900. Cairo, like other cities throughout the state and the nation, became more modernized. The city provied new services, such as water and electricity, although the latter was largely confined to buildings and businesses; few homeowners could afford this luxury. The electric streetcar also came to town. Although many people welcomed this new transportation, it created problems too. Unaccustomed to watching for fast-moving, motorized vehicles, pedestrians were sometimes startled—and a few people even hit—by streetcars. Scott also saw the African-American community grow larger. By 1900 Cairo had 13,084 white and 6,300 black citizens.

16 Most blacks who moved to Cairo were unskilled laborers, but some were skilled artisans, professionals, and businessmen. The all-black schools generally were taught by African-American schoolteachers by the 1880s. Thus, teachers became the most numerous professionals. Highly respected, the teachers were also very active in the African-American community and sometimes within the larger society. Several black doctors lived in Cairo, including Dr. Holly, who was sometimes employed by the city. African-American ministers served the many black churches. The African Methodist Episcopal and the Baptists were the two denominations with the largest memberships. Blacks from neighboring Pulaski and Massac counties, as well as elsewhere, sometimes came to Cairo to attend social activities such as dances and picnics. Many events were sponsored by the Masons and Eastern Stars, the Knights of Labor, and other fraternal societies and sororities. William Scott, who was an officer in the Knights of Labor, was often present. Many new businesses, some owned by African-Americans, sprang up in the growing city of Cairo. Ice cream parlors, bakeries, shoe repair shops, restaurants, and saloons stood along its busy streets. Several African-American newspapers, including Scott's Gazette, the Sentinel, and the Hornet, were published there. New churches, additional private and public schools, assorted benevolent and fraternal societies, and the new public library were all established during the time that William Scott lived in the city. African-Americans in Cairo established a strong black community that included institutions such as schools, churches, and benevolent and fraternal societies. This community helped them to combat racism and to challenge restrictions that they commonly faced in nineteenth-century America. Thus, in the Reconstruction and post-Reconstruction eras African-Americans in Illinois gained rights previously denied them, including the right to vote and to hold public office, as well as the right to free, public education. Despite important gains in these areas, racial inequality remained a feature of their lives. Discrimination in jobs and segregated schools, restaurants, and other public accommodations was still commonplace in Cairo at the end of the nineteenth century. Click Here for Curriculum Materials 17 |

|

|