Road

to riches?

Interstates mean profits for some towns, poverty for others.

by Pat Harrison

|

No one considers it newsworthy

when Chris Langston and his fellow

horologists eat or stay overnight in El

Paso. But the money these clock collectors spend in the town five times each

year reflects the way interstate highways affect the communities they pass

through — as well as those they bypass.

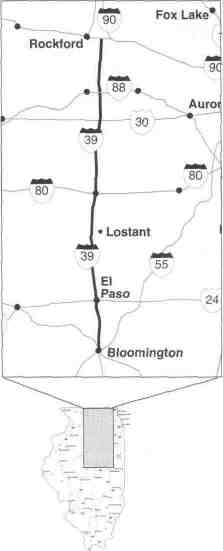

When Interstate 39, which intersects

El Paso, was completed in 1992, it was

hailed as part of a major transportation

artery that stretched from Canada to

the Gulf of Mexico. Since then, it has

become an economic boon for several

small Illinois communities between

LaSalle and Bloomington.

Highway exits have attracted new

businesses to the off-ramp towns. New

businesses have meant more jobs and

more sales and property tax revenues.

And more revenues in city coffers have

paid for improved roads and increased

city services. "The interstate has

allowed the city to do a lot of infrastructure work," says El Paso resident

Frank Iskrzycki. "We've kept the smalltown effect on one side and have the

opportunity and advantages of having

all the business on the other."

In El Paso's case, the interstate has

meant a permanent home for Central

Illinois Chapter 66 of the National

Association of Watch and Clock Collectors. The group has been meeting in

El Paso for eight years, but about two

years ago considered moving because it

was outgrowing its meeting space in a

local restaurant.

The group conducted one meeting in

East Peoria. But members returned to

El Paso because 1-39 allows easy access

to a central location. "Most of our 125

members are from Wisconsin, Chicago,

Rockford and Moline and use 1-39

heavily," says Langston, a Peorian.

"One gentleman from Chicago said it's

only two hours from his front door."

Such access has spawned the building of motels, fast-food restaurants,

antique shops and homes in El Paso,

which has meant hundreds of thousands of dollars for the city. Sales tax

revenue jumped from $252,527 in fiscal

year 1991 to $567,235 in 1995.

The extra money is helping to pay

for infrastructure improvements — utilities, roads, water and sewer lines — that are being used to attract still more

business to the 1-39 interchange. The

city has been able to landscape a new

40-acre park with a swimming pool,

tennis courts, community center and

baseball diamonds. It has built a new

water plant and put up a new public

works building, which houses the local

police department.

The increase in sales tax revenue has

meant less reliance on taxpayers to run

this Woodford County community of

2,500, says city administrator Ted Gresham. He says the city's property tax

rate dropped from $1.33 per $100

assessed valuation in 1992 to $1.09

three years later.

Yet now El Paso must contend with

the growth that comes with being accessible. On the plus side, new homes and

businesses helped swell property tax

coffers. School Superintendent James

Miller says the extra property tax rev-

|

28 * February 1996 Illinois Issues

enue has allowed the district to spend

$100,000 to renovate a science classroom and buy computers for local

schools.

But these schools must now contend

with overcrowding. Real estate agent

Don Sutton says easy access to 1-39 and

Bloomington, where many residents

work, has lured many homebuyers. All

59 lots in one subdivision were sold in a

five-month period. Growth like this has

caused the school district's enrollment

to jump an average of 7.5 percent yearly since 1987, Miller says. Enrollment is

at capacity now, with 970 students in

kindergarten through 12th grade.

But a referendum for more classroom space seems a remote possibility.

"The community is going to have to see

a larger need than now," says Miller.

"As we experience growth, which we

anticipate, space is going to become a

major issue."

Such potential problems seem

worthwhile, though, to towns that otherwise might have died without 1-39.

Consider Oglesby, a town of 3,700 residents about 40 miles north of El Paso.

If not for the interstate, says former

Mayor Gerald Scott, Oglesby could

have disappeared from the map. "We

had no way to support our police

force," he says. "And it's an older town.

All the young kids were leaving the area

because there were no jobs."

Since the completion of 1-39, four

restaurants, two motels and two gasoline station-convenience stores have

been built in Oglesby. The population

has stabilized. Much of the sales tax

revenue, which increased from $89,475

in 1986 to $330,159 in 1994, has been

used for street repairs. And in October

came announcement of an 800,000-square-foot distribution facility that

will employ more than 500 people. A

key reason it is locating in Oglesby is its

proximity to convenient transportation.

"1-39 has opened up this area as an

interesting location for warehousing

and transportation-related firms," says

Barb Koch, executive director of the

Illinois Valley Area Chamber of Commerce. "1-39 allows the area to be centrally located to any market."

Just north of El Paso is Minonk,

which has started to see benefits from I-39 but has yet to realize the largesse it

has supplied Oglesby and El Paso. Yet

such a future appears imminent. The

Woodford County community of 2,000

has seen its sales tax revenues rise by

more than $20,000 since fiscal year

1989, though downtown Minonk is

more than a mile from the interstate,

according to city administrator David

Shirley. "There are a lot of out-of-state

cars coming in," he says. "Restaurants

are benefitting, and I've noticed some

outdoorsmen shopping at the grocery

store."

At the same time, the city's property

tax rate has been lowered by almost 50

cents, primarily due to new residents

building or buying. To capitalize on the

potential growth, the city invested $1.18

million to buy and provide infrastructure for 26 acres northeast of 1-39.

James Letsos of Pontiac plans a sit-down restaurant with a minimum seating capacity of 175 in Minonk, plus a

truck stop-convenience store. He

expects to provide 50 to 70 full- and part-time jobs when the development is

completed this year.

In mid-October, Wenona began capitalizing on 1-39 when a fast-food/service station opened at its exit. A restaurant and motel are expected to open in

February or March, says Mayor Bill

Simmons.

So while an interstate can keep

groups like the clock collectors coming

to town for the sake of convenience, its

overall impact on a community can

expand well beyond a few extra fast-food meals purchased and motel rooms

rented. *

Pat Harrison is the city editor of the

Daily Times in Ottawa.

|

As for those who are bypassed:

'You could shoot a gun without hitting anything.'

Just as an interstate can breathe economic life into a community it

passes through, it can suck business away from others.

"Towns which interstates bypass tend to lose 25 to 30 percent of

their businesses in the first year," says author Tom Teague, who has

researched the history and impact of U.S. highways for his book

Searching for 66.. "Some old-timers tell me that when interstates bypass

them, it is like turning off the tap."

That's been the case in Lostant, about 40 miles north of Bloomington. After Interstate 39 was built, bypassing the village, a gas station-convenience store there closed, leading to a severe decline in sales tax

revenue.

Without the revenue, says village trustee Randy Freeman, Lostant

has no money to repair sidewalks and streets. Nor is there money to

install a sewer system that village officials need to attract business.

"People have said they missed the turnoff," says Freeman, who circulated petitions asking the state to erect a sign at the interstate exit

nearest Lostant.

A few miles north, the opening of 1-39 almost meant a death knell

for the Village Inn restaurant and truck stop in Tonica. It took some

creativity — and a bit of private investment — to pick things up there.

"Business went down 80 percent for about nine months," says Lois

Dellinger, a bookkeeper at the restaurant. "You could shoot a gun

without hitting anything. Truckers don't pay any attention to the exit

numbers."

Business improved, though, once the restaurant's owners convinced

state officials to put up a sign alerting motorists that food, gas and

diesel fuel were available at the exit nearest to Tonica. The Village Inn

pays $1,200 a year for the sign.

Pat Harrison

|

Illinois Issues February 1996 * 29