FADE TO BLACK

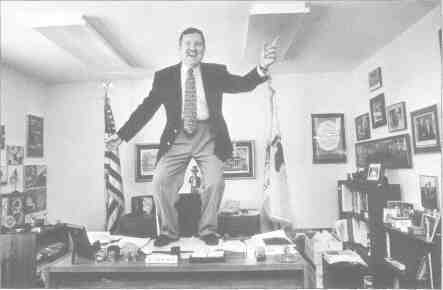

Story by Michael Hawthorne The shift in the state's population is reflected in the legislature, where Republican suburbanites have emerged as the dominant force. As downstate disappears from the political map, Danville Republican Bill Black remains one of the most passionate defenders of his region. He relies on the same mix of determination, humor and unconventional behavior that has earned him a reputation as one of the most entertaining, if not eloquent, speakers in the General Assembly. 12 ¦ July 1996 Illinois Issues Bill Black contradicts what most political consultants want in a spokesman for the GOP revolution. A short, barrel-chested man with a mustache more reminiscent of a German hofbrau owner than GOP poster boy Tom Selleck, the Danville Republican is the first to say he isn't telegenic. What's more, while Republicans were swept into power by a surge of GOP voters in the burgeoning Chicago suburbs, Black is a downstater with a dwindling constituency rooted more in farming and a decaying industrial base than the new technology-dependent economy exemplified by suburban companies like Motorola. A casual observer might wonder why House Speaker Lee Daniels, an Elmhurst Republican, tapped Black to be his floor leader. Black mouths off against property tax caps, a top Republican priority. He challenges big business — the financial backbone of Republican campaigns — by going public with his doubts about reforming workers compensation laws. During one of his signature tirades on the House floor, he told the GOP-controlled Senate to "go to hell" for refusing to negotiate on a pet bill. Some Republican ideologues privately suggest Black is a heretic for maintaining friendly ties with minority Democrats. Imagine a Republican storming out of the House chamber and preparing to drive home because an aide (Daniels' former Chief of Staff Mike Tristano) ordered GOP legislators to change their votes and oppose a Democrat-sponsored bill. Black did just that two years ago after promising to deliver enough Republican votes to pass the bill in return for Democratic votes on another measure. Although the Democrat (former Rep. Gerald Hawkins of DuQuoin) was a top GOP target for defeat, partisan politics wasn't going to stop Black from following through on his promise. "There are people who don't know what I am, which hasn't always endeared me to some Republicans," Black says. "There's no doubt I'm different from my suburban colleagues, but that's due in part to the vastly different areas we represent." William B. Black, 54, has lived nearly all of his life in Danville, a city nestled along the Illinois-Indiana border 35 miles east of Champaign-Urbana. In an age when it's common for people to pick up and establish roots in other cities, he can drive along his childhood newspaper route and rattle off the names of his former customers. His district office is five blocks from where he grew up and down the street from Danville High School, where he was a guidance counselor for several years. His first girlfriend lived in the house next door to the office parking lot. "Many of my high school friends are solid union members, and I talk with more of these people on any given day than my suburban colleagues," Black says, explaining his willingness to question the GOP's pro-business agenda. "It doesn't matter where I go in town, be it a coffee shop or a hockey game, somebody recognizes me and wants to talk." His constituents have a lot to talk about and much of it isn't good. Danville and Vermilion County have yet to recover from economic recessions and the corporate merger mania that decimated the area's industries in the 1980s. Other Rust Belt cities like Peoria are bouncing back, but vacant limestone buildings lining Danville's downtown only hint of their past grandeur. One of the most heralded — and controversial — new businesses in town is the Wal-Mart on the city's north side. By contrast, most of the Republicans who now control the Illinois General Assembly hail from the six counties surrounding Chicago, which are swelling with new businesses, corporate headquarters and residential development. The shift in population away from Chicago and downstate is reflected in the General Assembly, where suburbanites have emerged as the dominant political force. As an assistant majority leader, Black remains one of the most passionate and vocal defenders of downstate issues. He relies on the same mix of determination, humor, sarcasm and unconventional behavior that has earned him a reputation as one of the most entertaining, if not eloquent, speakers in the General Assembly. Some of his suburban colleagues have made careers out of bashing O'Hare International Airport for the incessant noise and the stranglehold Chicago Democrats have on lucrative airport contracts. Black half-jokingly tells them to move the airport to Vermilion County if they're so upset. "We'll take the problems," he says. "We would love the jobs and the incredible economic engine that airport has been for the suburbs." Black also is quick to anger and is more than willing to direct his fury at Democrats or fellow Republicans. Some of his exchanges with other legislators are the stuff of legend. In a confrontation that highlights the differences between downstaters and suburbanites, Black and Rep. Terry Parke, a Hoffman Estates Republican, began shoving each other during a 1992 debate over a proposed constitutional amendment to boost education funding. Downstaters from both parties generally favored the amendment because their schools would get more state money under a complex formula that favors property-poor districts. Suburbanites believed their more affluent constituents would end up paying for the plan through higher income taxes but wouldn't see any of the benefits. As the debate raged on, Black and Parke wrestled each other into a chair before other legislators pried them apart. "We've had our differences over the years, but I respect Bill for standing up for what he believes in," says Parke. Parke and other Republicans also remember Black as the "designated screamer" who stood up for them when Democrats controlled the House. Black's emotional defense of Republican interests during those often bleak years in the minority landed him in the hospital on several occasions. He would fiercely complain when Democrats refused to call GOP bills in favor of similar legislation with Democratic sponsors. During one memorable exchange, he threw a rule book at the speaker's rostrum while ranting about Illinois Issues July 1996 ¦ 13

the Democrats' refusal to consider a Republican-sponsored amendment. After an exhausted Black was rushed to Memorial Medical Center in Springfield in May 1994, the doctor asked if he was under any stress at work. Black laughed. The doctor told him to stay in his office and rest, but less than 15 minutes after returning to the Capitol, Black was back on the House floor denouncing an amendment rammed through by the Democrats. He screamed as loudly as he had earlier in the day. "He certainly isn't shy," quips Daniels, who rewarded Black for his hard work and loyalty by keeping him on the GOP leadership team when Republicans won control of the House in November 1994. Although he is willing to challenge his friends and flout the party line, Black can be intensely partisan, even if he's merely feigning anger to get results. When Democrats complained this spring about a package of ethics and campaign finance reforms that was stripped down to a single provision — requiring legislators to name the winners of General Assembly scholarships — all eyes were on Black as he slowly stood to respond. "Welcome to the greatest show on earth, the Ringling Brothers and Barnum, Bailey and Cook County Circus," Black said. "Yes siree. The party that doesn't know how to spell ethics. The party that brought us the meaning of the word corruption in the city of Chicago: Greylord, Bluelord, Nudelord, you want me to go on? I don't know how some of you people can shave in the morning, because it's hard to do when you are looking away from the mirror. "Here we are ranting and raving about something that almost every one of you are going to vote for," he said, gesturing wildly like a tent-revival preacher. "I'll make you a deal: I'm not sending out a press release on anything that goes on today. You do the same. Better yet, amend this thing on its face and abolish the press staff of both parties." Minutes later, he walked over to a group of Democrats and they all laughed. Good show, the Democrats said. "He certainly is a Republican and is much more conservative than I am, but I consider him a good friend," says Rep. Louis Lang, a Skokie Democrat who inherited Black's job as spokesman for the minority. "When we were really going at each other last year, many of the freshmen at first thought we were arch enemies and had a vendetta against each other. Nothing could be further from the truth." Echoing the comments of other legislators, Lang says Black works best when he turns his intensity on legislators and bureaucrats on behalf of his constituents. For instance, weary of the reams of bogus Chicago parking tickets forwarded to him by folks back home, Black orchestrated a media-savvy campaign this spring that forced the city to clean up its act. First he captured the attention of Chicago officials by introducing legislation banning the city from enforcing tickets issued to people who live outside the city. Then he dragged city officials to Springfield for several hearings where he and other legislators could exhaust their litany of complaints. Chicago officials responded by crafting new policies intended to resolve disputes quickly. They also promised to slash the number of bogus tickets. "I didn't believe some of these people at first because what they were saying seemed so ludicrous, but as we looked into it we realized they were right," Black says. "I would get stonewalled trying to explain to some bureaucrat that the person they issued a ticket to is 80 years old and her car hasn't been out of the garage for years. It made me so mad, and I tend to internalize things like that." Another one of Black's crusades this year involved a depleted fund for widows and orphans of workers killed on the job. Most suburban Republicans are considered enemies of organized labor, but Black fought for two years to bail out the fund. It was the right thing to do, he says, because five people waiting for their benefits live in his district. It appeared the measure would flounder again this year as legislators prepared to adjourn for the summer, but then Black cut a deal with business groups and combined it with an unrelated bill allowing employers to give job references without fearing lawsuits. 14 ¦ July 1996 Illinois Issues The raucous House chamber fell silent when Black rose to counter Democratic complaints that the GOP was "using widows and orphans to pass a business break." "I'll walk through this chamber in my bare feet on crushed glass if you want," Black bellowed. "I'll sit down in the front and I'll beg and I'll cry, if that's what you want. If it makes you feel any better, send out a brochure to everyone in my district and say what a no-good, evil, double-dealing downstater I am. "But the bottom line is this: I'd like to go home tomorrow and see Shirley Golden, a widow, and say I did everything I could do to see that she gets paid what is due her because her husband died while fighting a fire in Vermilion County in 1983. Is this bill perfect? No! Did I have to swallow hard for another part of the bill? Maybe I did. But you come with me and you look Shirley Golden in the eye and say you couldn't vote for this because there was a part of this bill that you didn't like." The bill passed, albeit with 43 Democrats voting present. "I always tell groups I'm speaking to there are two things you don't want to see made: sausages and laws," Black said later. "But the process is so much better than anything anybody else has come up with." Reflecting the divergent views of businesses and workers from his district on workers compensation laws, Black followed a more moderate path than his suburban colleagues when the issue was included in a GOP package of pro-business legislation last year. The son of a heating and air conditioning contractor, Black grew up in a culture where government regulation often meant endless paperwork and seemingly contradictory regulations for small businesses. Yet beginning at age 15 he worked alongside laborers unconcerned about venting their frustrations with the workers compensation system on the boss' son. "My brother still runs the family business, and he isn't shy about telling me that workers comp costs are killing him," says Black. "But you get a different feel for how hard this work is when you're lying on your back trying to hold up a 6-inch cast iron pipe for an industrial boiler. You realize how easy it can be to get hurt on the job." The reforms proposed by business groups last year concentrated too much on cutting costs and not enough on making it easier for legitimate claims to be processed quickly, Black says. The bill was killed following a dispute between business groups and physicians over a requirement that recipients enter managed health care plans, but Black was one of the few Republicans who publicly questioned the proposal. If that didn't cause enough headaches for Daniels, Black threatened to resign his leadership position last year during a dispute about downstate property tax caps, another item on the speaker's agenda. After Daniels held the bill so downstaters could hold hearings back home. Black voted this spring for another measure allowing downstate county boards to hold tax cap referendums. Nevertheless, he fears the limits could hurt downstate school districts and local governments still recovering from a decade of declining property values.

"Other than a few isolated pockets, we just haven't seen the skyrocketing growth the suburbs have experienced during the past 20 years," says Danville School Superintendent David Fields, a friend of Black's since they started together as teachers in the early 1960s. "Bill has done an admirable job representing the interests of schools in his district and all of downstate." Says Black: "On tax caps, it came down to a compromise that allows people at the local level to decide. I can count, and I realized that one of these days these suburbanites might wake up and realize they could impose tax caps on us no matter what we say." He credits Daniels for his willingness to listen to disparate views within the Republican caucus. Black also differs from many of his Republican colleagues who push the "welfare queen" stereotype. It's not uncommon to find men and women who spent decades working at the now-shuttered General Motors foundry and other Danville-area plants now collecting welfare benefits or struggling to learn new skills at the local community college. While Black voted to abolish the state's existing Illinois Issues July 1996 ¦ 15 welfare programs, he wants to retain a social safety net and concentrate more on state programs that help people find meaningful work. "The mental picture we have of welfare is not really what it is today, especially in my district," he says. "There are people on public aid who in their wildest imagination never believed they would be there. But when you have a number of factories move out and many of these people laid off are older without the necessary skills, it creates real hardship." Hailing from a county where many local officials are Democrats, Black's pragmatism has served him well back home. Since winning his seat by just 1,500 votes in 1986, he has faced token opposition in two of the following four elections. He dispatched his 1994 challenger with 78 percent of the vote. As an administrator at Danville Area Community College in the late 1970s, Black followed his father into politics. Black served on the Vermilion County Board with his father, Willard "Blackie" Black. Bill Black later served as county board chairman for two years before moving to the General Assembly. "Bill is a very likable fellow who seems to know everybody and attends virtually every community event," says Roger Boen, chairman of the Vermilion County Democratic Party and Black's 1992 opponent. "I don't think anybody will ever be able to beat him." Democrats couldn't find anyone willing to challenge Black this year, but a severe illness almost cut short his career in 1990. He walked into a local hospital complaining of flu symptoms and ended up hospitalized for six weeks with viral pneumonia.

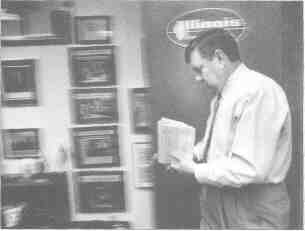

"The doctors said I almost died," Black says as he leans back in his chair at his district office. Surrounded by plaques, a portrait of Abraham Lincoln, a statue of Uncle Sam and a picture collection of past and present players for his beloved Chicago Cubs, he says his eating habits and his tendency to flare up over the smallest issue are drawbacks. His wife, Sharon, often calls him in Springfield to urge restraint. But he didn't come to Springfield to be a backbencher. On top of a stack of papers waiting to be filed is a newspaper picture of a red-faced Black telling counterparts in the Senate to "go to hell" if they refused to negotiate on a bill allowing county jails to lock up young criminals instead of transporting them to a handful of juvenile detention centers. Black worked on the legislation for four years with his late friend Jerry Chrisman, the Vermilion County probation officer. Sending youths to the centers is expensive. If facilities are full, authorities often release the kids pending a court hearing. County officials say they have room to house young criminals away from adults, but state law prohibits it. After Chrisman committed suicide last April, Black redoubled his efforts. He broke down several times as he told colleagues about his friend. He begged them to pass the measure, only to see it stall in the Senate. "This has become a very personal issue with me. I make no apologies about that," Black said this past May when the issue was before the House again. That time both chambers approved the measure. Chatting with a visitor in his district office, Black points wistfully to a plaque near the door that features a picture of Chrisman. As young Republicans in the 1960s, they spoke idealistically about changing the world, he says. But democracy is an incremental process where ideas rarely are approved as they are proposed. Politicians often are forced to recite the mantra of Cubs fans like Black: Wait until next year. Black is uncertain about his political future. He once aspired to succeed Sen. Harry "Babe" Woodyard of Chrisman, but Senate President James "Pate" Philip has made it clear Black's bombastic style wouldn't be welcome in the upper chamber. Friends and family caution Black that he takes his job too seriously, but he genuinely enjoys it. A bumper sticker on his office door reads, "Humor: Don't leave home without it." "If this was a perfect world, I would be 6-feet-6, a heck of a lot better looking and weigh 50 pounds less," he says. "I don't think I'm going to live to be an 80-year-old elder statesman, but at least I can say I tried to make a difference. And I had fun while it lasted." Michael Hawthorne is the Statehouse bureau chief for The News-Gazette of Champaign. 16 ¦ July 1996 Illinois Issues

Black 's legislative district has been hit hard by economic shifts. He says as a kid he could always get a glass of cold water at this long-abandoned fire station. Built in 1898, the station housed an African-American firefighting unit. Illinois Issues July 1996 ¦ 17 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Sam S. Manivong, Illinois Periodicals Online Coordinator |

![As a kid [Black] could always get a glass of cold water at this long-abandoned fire station](ii9607125.jpg)