GYM TEACHERS ON GUARD Schools move to drop dodge ball by Susan Houseworth Herrel In the small Illinois town of Antioch, nestled in the rolling hills near the Wisconsin border, school officials have decided to allow students to substitute one semester of music or foreign language for physical education. Debbie Kerr, principal of Antioch Upper Grade School, says she recommended this option to the school board in 1995. "To a lot of our parents, band and choir are just as important as English and math," she says. She emphasizes that the sixth-, seventh- and eighth-graders at her school still have a chance to be active. "They are allowed to go outside after lunch for a 20-minute recess every day," she says. Antioch is one of 88 school districts — from Anna in far southern Illinois to Zion in the state's northernmost reaches — that have taken advantage of a year-old state law allowing them to change their P.E. requirements. School officials are happy about the flexibility it gives them in designing their class requirements, but the move has turned into a wake-up call for gym teachers: They'll have to improve their classes if they want to keep students interested and keep P.E. as part of a district's curriculum. The new law stipulates that a school district can petition the Illinois State Board of Education to waive a state mandate, including P.E., if it can show that a change will address the subject at hand in "a more effective, efficient or economical manner or when necessary to stimulate innovation or improve student performance." If a waiver is approved for one district, any other school may follow suit and apply that waiver to their students' schedules.

Only 19 percent

of all high school

students are

physically active

for 20 minutes or

more in classes

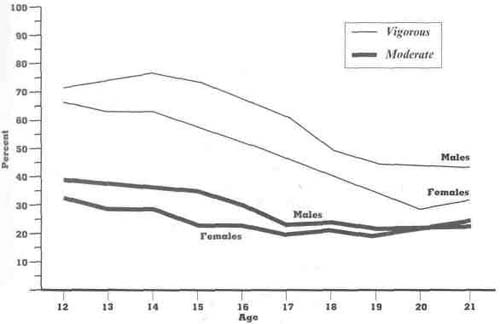

every day during

the school year. So far, schools are taking lawmakers up on the offer with a vengeance. Yet, the move away from P.E. in Illinois comes as the U.S. surgeon general is telling Americans that inactivity is "hazardous to your health." The report recommends schools provide "quality, preferably daily, physical education classes." Lamenting the report's findings — including that just 20 percent of Americans meet guidelines for moderate activity of 30 minutes most days — Vice President Al Gore said the nation is adopting a "couch-potato culture." The report ranked states by level of physical activity per capita; Illinois was among the more sedentary at 34th. Even so, the state is following a national trend away from P.E. classes. Across the country, daily enrollment in P.E. among high school students dropped from 42 percent to 25 percent between 1991 and 1995. Although Illinois now is the only state that still requires students to take one hour of P.E. every day throughout their public school career, the mandate is being eroded by tight budgets and an increased focus on academics, says Mary Kennedy, president of the Illinois Association for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance. 22 ¦ September 1996 Illinois Issues Physical activity levels of adolescents and young adults, by age and sex

Source: CDC 1992 National Health Interview Survey, Youth Risk Behavior Survey

In the past, there have been ways for individual students to get around the requirement, certainly. Many Illinois high school students, especially varsity athletes, can opt out of P.E. because educators believe they get adequate physical activity through their sport. But Illinois' new law has opened the door for schools to minimize P.E. requirements further. Applications for P.E. waivers offer a variety of reasons for opting out. Some school districts, like those in the burgeoning suburbs, say they don't have enough room to offer gym classes. Some want to give students more time to participate in extracurricular activities. Others are motivated by academics. They want to allow students more time to take such electives as foreign languages or computers. They want to schedule college-bound students into advanced courses. Or they want to allow students who have failed courses to make up their credits. Illinois Issues September 1996 ¦ 23 In fact, some educators say they're afraid P.E. will be eliminated entirely from students' schedules in an attempt to enhance their academic education. Such a move would produce a student with an impressive school transcript but a major weakness, says Beth Mahar, a P.E. teacher in the Homewood/Flossmoor district. What we'll have is a highly qualified high school graduate who won't be physically fit or healthy enough to walk around the college campus of his or her choice, she says. Dick Lockhart, a lobbyist for the P.E. teachers' organization for 20 years, was not surprised at how quickly the new law affected P.E. programs: "There is so much frustration with education by political people." Mahar agrees: "They want to do anything that they think will improve education in general. In essence, the state said, 'We won't give you any more money, but now we'll give you a tool to allow you to cut your own budgets.'" In the early '60s, the surgeon general's report on tobacco brought about an all-encompassing war on smoking that has snowballed into the well-known warning: "The surgeon general has determined that smoking is hazardous to your health." Jeff Sunderlin says he thinks the report on physical activity will be just as significant — a wake-up call that gym teachers can't ignore. "The heat is on to become very good at P.E," he says. As program administrator of the Governor's Council on Physical Fitness and Sport in Springfield, Sunderlin says one of his responsibilities is to help physical education teachers realize the importance of community support. "P.E. is not one of the three R's," he says. "It will take a great deal of energy for teachers to get their message across." He agrees with the surgeon general's report, which recommends that schools be encouraged to keep daily P.E. classes. But the status quo isn't good enough. For several decades the trend for P.E. classes was toward a sport-specific education; Sunderlin believes a more holistic approach incorporating lifelong health activities and benefits will be more effective. Now he is part of a team sponsored by the Illinois State Board of Education that has been working on new content standards for P.E. classes. He hopes these standards and guidelines will help teachers adjust curriculums toward more flexible state goals. This pressure already is being felt at the college level, where P.E. teachers are trained. Kim Graber, professor of kinesiology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, says the profession has to take some responsibility for what has happened to the program overall and how generations of P.E. students have been affected.

A 1993 survey

found 43 percent

of Americans

age 6 and over

exercise no more

than one day a

week. Thirty-one

percent said they

exercise two to

three times, and

26 percent

exercise four or

more times. "People realize that P.E. has been an inadequate motivator," she says. "Kids generally become more sedentary as they get older, but their negative experiences in P.E. classes also make them want to be inactive." There are teachers out there, Graber says, who have used inappropriate or ineffective teaching methods that have caused pervasive negative feelings about P.E. Using exercise as punishment ("Take a lap!" or "That'll be five push-ups!") or taking a drill sergeant approach perpetuates negative feelings about exercise. Indeed, P.E. doesn't get much respect. Students and other teachers sometimes consider P.E. classes less important than English or algebra, for example. What's more, says Graber, many schools have a no-grade system with P.E., in which students receive a pass/fail grade. This relieves pressure on students who do not perform game skills well, but also gives them the impression that performance, attendance and learning in P.E. are not as important as in other classes. Some argue that P.E. has become an expendable subject because it has been ineffective at maintaining and improving children's fitness levels. But Sunderlin finds fault with this logic. "Why preserve and maintain P.E. when it hasn't been working? Reading levels have dipped, and they didn't drop reading from the schools — they enhanced and bettered the curriculum," he says. Robert Nielsen, assistant superintendent of Urbana's District 116, says there's a better chance of improving quality when educators have more control over their curriculum. "Part of the problem with education is that we're so locked into mandates," he says. "Right now there is no incentive to improve the P.E. program that they offer because kids are mandated to take it. If you want to see significant improvement in P.E., make it an elective." This would force P.E. teachers to offer an attractive program that children will be tempted to take, rather than a required class that is marginally effective, he says. If P.E. teachers step up to this challenge, children could be trained to see exercise as a good thing. If not, Illinois could slip further into the "couch-potato culture" And gym classes could end up going the way of one-room school-houses and Latin lessons. Susan Houseworth Herrel, a free-lance writer, lives in Savoy. 24 ¦ September 1996 Illinois Issues |

||||||||||||||||||