BISON AND BOBCATS AND BEARS! OH, WHY?

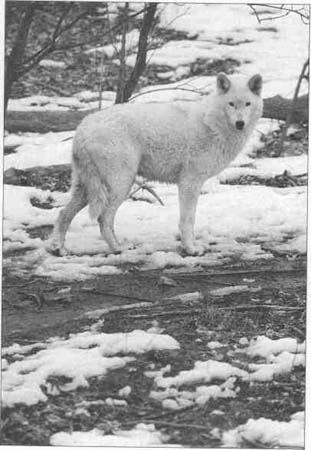

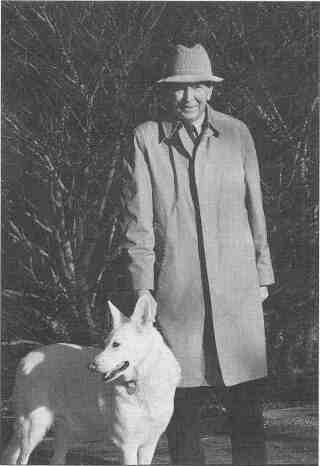

Story by Tara McClellan McAndrew Bill Rutherford's late-model station wagon charges down a winding gravel road and pulls into a construction site. Here at his Wildlife Prairie Park, the Peoria native says, grain bins will be reborn as hotel rooms. But for now, tools and debris are scattered everywhere. To anybody else, that would mean the project's completion is weeks away. Not to Rutherford. As he surveys the scene he announces it will be ready "tomorrow." Rutherford's vision might seem overly ambitious, yet he remains determined to beat the odds. In some ways he already has. Here's a man who has carved about 2,000 acres out of central Illinois for his own nature park. Before he envisioned it, and made it happen, no one had thought of letting bobcats, bears and bison run free as they once did on a stretch of prairie 10 miles west of his hometown. And, at 81, he still has the energy and the will to turn his dreams into bricks and mortar. But these days the former state conservation director is facing his toughest challenge: securing a future for his creation, which has been appraised at $19 million. The best way to do that, Rutherford believes, is to give the park to the public. Unlike his construction schedule, though, this plan is not under Rutherford's complete control. Indeed, he's been having trouble finding takers. Peoria park officials turned the gift down, saying they couldn't afford to maintain it. Efforts by Bob Michel, Peoria's former congressman, to convince national park officials to take over the project also came to nothing, though Michel did manage to get George Bush's secretary of the interior, Manuel Lujan Jr., to visit the park. In what would appear to be a last-ditch effort, Rutherford has now turned to Springfield. But state officials have been hesitant, too. After the Department of Natural Resources initially rejected the offer, Lt. Gov. Bob Kustra agreed to give it a second look. Kustra, who is sympathetic to Rutherford's efforts, helped establish a new license plate as a fund-raising tool for the park. Lawmakers approved the plate in the spring, and Gov. Jim Edgar signed the measure at the state fair last month. The plates, which will be available after the first of the year, will cost an additonal $40 for the original plate and an additional $27 for renewal. Of those fees, $25 will be set aside for park improvements and maintenance. The legislation also created a Sportsmen Series license plate that would provide additional funding to enable the natural resources department to acquire, develop and manage other wildlife habitat. "Preserving our natural resources is an obligation we owe to the generations that will follow us," Edgar said in a printed statement after signing the bill in Conservation World on the fairgrounds. Meanwhile, Kustra, along with his staff, is exploring a public/private partnership to run the park. But his aide, Jim Bray, says any arrangements for state ownership are only "in the discussion stages." It could be a tough sell for Rutherford because the private park runs about a quarter of a million dollars in the red every year. Still, he believes the state can afford it and should be happy to take it over. Yet it's not that simple, and it's not that easy. The park is more than a habitat. Like its owner, it's hard to classify. It's part nature preserve, part zoo, part theme park. And part personal monument. The park will always be a testament to Rutherford and his ideals, says Jim Fowler, America's well-known wildlife spokesman. Fowler, host of television's Mutual of Omaha's Wild Kingdom, helped design Wildlife Prairie Park almost 20 years ago and went to bat for it again during a recent tour with Kustra. That tour, and the resulting discussions with the state, make Rutherford hopeful he'll get his way. It must gall him, though, to turn to politicians and bureaucrats. He says he created the park in the first place because government wouldn't. And a plaque on one of his buildings reads, "Bureaucracy breeds hesitation and absurdity." 26 ¦ September 1996 Illinois Issues In fact, during his own short stint as head of the Illinois Department of Conservation (now part of the Department of Natural Resources), he managed to irk plenty of people. That was in 1969, "the longest year of my life," Rutherford says, remembering his tenure with Republican Gov. Richard Ogilvie's administration. Not everything Rutherford did while director was considered a faux pas, certainly. He managed to acquire more public land for Illinois in one year than the state had acquired during the previous three. But, according to news accounts at the time and to those who recall the controversies, Rutherford angered political leaders while delighting conservationists. He resisted the tradition of passing out prized deer hunting permits to state officials on a partisan basis and shut down the Wicker Club, their hunting lodge playground in southern Illinois. More critically, according to the same sources, he refused to put some of Ogilvie's mansion expenses in his agency's budget. And he shook up the department's traditional reliance on patronage. Rutherford resigned after taking heat from state lawmakers for eliminating jobs and perks. Although he no longer officially led the state's conservation efforts, Rutherford believes he continued to lead by example. His family's Forest Park Foundation helped Australia secure 620,000 acres and acquired 20,000 acres in central Illinois for public use and habitat preservation. Then, in 1978, after Brookfield Zoo in suburban Cook County abandoned plans to establish an endangered species habitat on some land near Peoria, Rutherford and officials in his foundation decided to build the park and do it their "own way." Now that park is a place where the buffalo really do roam over rolling vistas — along with deer and antelope. Approximately 200,000 visitors a year pay up to $4.50 each to watch them graze on recovered strip mine land and to walk trails for a closer look at birds of prey, waterfowl, wolves and cougars. They can attend educational programs and camps, eat at Rutherford's restaurant or stay in his lodging. The park excels at reaching average people who aren't nature enthusiasts, according to Michael Reuter, director of conservation programs for The Nature Conservancy of Illinois. It shows them "what this place was like prior to settlement." Political scientist David Kenney agrees that Rutherford's mission is admirable, albeit difficult. "He wanted to build a theme park there. And he wanted to have interesting and dramatic and entertaining exhibits. And that can get pretty hard to do," says Kenney, an active conservationist who also once headed the state's conservation agency. Rutherford's primary vision is to provide a place where families can enjoy themselves and learn about wildlife and conservation. But that vision is expensive. It requires annual subsidies from his family's foundation, along with contributions, and profits from corporate and wedding rentals, as well as entry fees. But now he says he wants to step back from some of the operating details, and he believes he's close to achieving that with the state. "[The park] is a unique resource," says Kustra. "There isn't another piece of property privately owned, yet available to the public for people to reach back into the past and get a feel for who they are and where they've come from."

Should the public take

responsibility for one man's dream?

Illinois Issues September 1996 ¦ 27 But the state isn't willing to subsidize the park as Rutherford's foundation has. So Kustra has been considering an alternative. With Rutherford, Fowler and officials from the Brookfield Zoo (Wildlife Prairie Park's "sister park"), he's discussing a plan to create a nonprofit foundation. That foundation would be responsible for the park's day-to-day operations and fiscal health. Kustra says the state wants to ensure that it will be profitable, and he has asked Fowler to develop ideas for increasing attendance. Meanwhile, park supporters are organizing a capital campaign. They also hope the new license plate will pull in additional dollars. According to initial discussions, foundation members would represent the public and private sectors. Kustra and Rutherford often compare the arrangement to the zoo in Brookfield. That zoo is owned by Cook County but run by the Chicago Zoological Society, a nonprofit organization for which Rutherford was a trustee. Rutherford thinks a joint partnership would be ideal because taxpayers would hold the state accountable for managing the park well. "If [the park] is in government ownership and the public is dissatisfied with the stewardship, they can assert their interest politically." But Brent Manning, current director of the natural resources department, disagrees. "Take national parks as examples, or even some parks within the state of Illinois. There is deterioration, yet we still hear people say, 'no more taxes.'" The Nature Conservancy's Michael Reuter believes it would be better for the private sector to step into the breach. "Ultimately, we can't expect government to shoulder the load of all these kinds of things. I'd like to see a local partnership developed, but if the state has to step in and make that happen, it's worth it." State ownership with private stewardship does work at some parks, according to Fowler, who says red tape has thwarted progress at several municipally owned parks.

28 ¦ September 1996 Illinois Issues "It's difficult for a governmental agency to take the initiative to do something that's up-to-date or creative," he says, citing the national park system as an example. "They can't even get by a discussion of what their mandate is." Private sector involvement, he believes, would also provide management skills. "Often bureaucracy isn't designed to run a hotel, lodge or gift shop." Kenney says public ownership with private stewardship could represent the best of each sector's qualities — or the worst. At best, he says, the park could benefit from the private sector's emphasis on the bottom line and the public sector's "concept of the common good." At worst, the park might suffer from uncertain lines of authority. Manning believes the park could benefit from joint management. "Ideally, [that mix] should be such that [the park] does the good science and at the same time is economically solvent and will stay afloat under the harshest conditions." Yet his department has not been involved in the discussions because, as he puts it, the agency "shouldn't be in the business of managing zoos." Indeed, defining the park — and the state's role in such an enterprise — may be the toughest issue to resolve. Fowler, for instance, believes the park should make visitors realize that animals and ecosystems are important to their lives and that humans' actions threaten those ecosystems and ultimately themselves. Rutherford (below) has done a good job of building buildings, Fowler says. "[But] I think that the original concept of the prairie park needs a little more than some buffalo and elk out in a pasture." Rutherford also believes the park could be "far more effective," but his immediate priority is keeping it alive for future Illinoisans. "I'm not going to get licked on this one." Tara McClellan McAndrew is a free-lance writer in Springfield. She. has written for Illinois Issues about the environment and historic and cultural preservation.

Conservation biologists could protect our future ecosystem by studying the past Time present and time past/Are both perhaps present in time future,/And time future contained in time past. T.S. Eliot's observation could well apply to a recent study completed by the Illinois State Museum. An international team of scientists coordinated by the museum studied the patterns of past mammal migrations and reached conclusions that could be valuable to conservation biologists in the future. If, for example, we want to know what our world will look like in the event of global warming, we might search the past for evidence of what occurred during other environmental extremes. Museum scientists looked at the fossil record contained in their collections, compiled the information in computer databases and applied satellite-gathered images of Earth to produce maps showing changes in the geographic distributions of more than 200 mammal species for seven time periods during the last 40,000 years. The study, reported in Science magazine, showed that individual species have dispersed in different directions and at different rates in response to past environmental changes, including the glaciers that covered half of Illinois and then melted. This is contrary to traditionally held views that mammals migrated en masse as one community in the same general direction. What this tells planners of the future is that corridors of undeveloped land will be important for the movement, and therefore continuation, of individual species. Beverley Scohell 30 ¦ September 1996 Illinois Issues Conservation vs. Sustainability A conversation with naturalist Jim Fowler by Tara McClellan McAndrew For the past 30 years, Jim Fowler has been a wildlife advocate on such popular television shows as Mutual of Omaha's Wild Kingdom, the Tonight Show and the Today Show. He is president of the Fowler Center for Wildlife Education in New York and is the executive director of Mutual of Omaha's Wildlife Heritage Center in Omaha, Neb. The center works to increase awareness of the natural world and to encourage conservation education, especially at the community level. Fowler has served as a consultant to nature and animal parks, and has helped design the layout of several, including Chehaw Wild Animal Park in Albany, Ga., and the Animal Forest at Charles Town Landing 1670 in Charleston, S. C. He is working on what he calls "ecological parks," which display native wildlife in large, free- roaming habitats. Global Communications for Conservation and the National Council of State Garden Clubs have awarded Fowler for his environmental work. The following is an edited excerpt of an interview with Fowler about Wildlife Prairie Park near Peoria, which he helped design nearly 20 years ago. Q. What do you think of a park such as Bill Rutherford's that conserves, teaches about conservation and entertains? A. The future of captive animal displays in America is a big subject. There is no justification for having animals in captivity unless they're there for one of three things. One is to preserve the gene pool. Some of the zoos and larger parks are able to keep certain species of animals — for example some of the rare species from Africa — that may disappear. Once you accept that zoos are important, you need to restock them with animals that are not afraid of people or fences, so that we don't have to take them out of the wild. The third thing is that we need animals that we can make companions, animals that can be ambassadors in education programs. Q. What do you think of Rutherford's mission at Wildlife Prairie Park? A. I think there could be more clarification on what these animals are doing there and why that's important to humans. I'll tell you the mission I have for a park like that. It really isn't to tell you how wonderful animals are. It's to tell you what ecosystems are all about. If we just talk about animals and how wonderful they are, it goes over everybody's head. Your mission ought to be to show how the earth works. If visitors who come to a park don't go away thinking "this is important to my life," then it's a failure. Q. And that ties in with the park's ability to make a profit and sustain itself. A. Ecotourism is one of the strongest justifications for keeping open areas and keeping areas natural. Whether we like it or not, economic justification is the strongest incentive for saving anything. And it's high time people in our large conservation organizations start realizing that we have to figure out economic incentives for maintaining some of these areas. Q. That's the big question. A. There's tremendous potential because in America over 120 million people go to zoos and animal exhibits. That's more than attend all sporting events combined. There's not a reason in the world why that prairie park shouldn't attract people from all over the United States — with some additions and a different approach. The final analysis is this: It's very critical because we're at a time when the whole concept of why we want to save the natural world is changing. We're losing habitat rapidly. The point is that we have to understand what's happening to habitat. See, conservation is a management term we invented, but sustainability of resources is the law of the universe. Conservation is great. It's a safe, nice-sounding word. The states use it, Bill Rutherford uses it, the zoos use it. But guess what. If I go to Africa and go up to a black rhino I happen to know and I say, "Hey, you're lucky, I'm coming over here to conserve you," you know what he'd say to me? "Listen, I don't want to be conserved. I want to be saved. There are only 300 of us left." So the word is sustainable. Our education message has got to change, in my opinion. What we have to look at is how you make the prairie sustainable, if it's important to humans. And that's a lot different from conservation, because in conservation you eventually eat the pig, if you know what I mean. Q. You would teach sustainability? A. Exactly. That's the future. And that's why that park is so critically important. Q. You 're saying it has a lot more potential that has not been tapped. A. And that's why I believe the future is going to be large parks like that, that do have space and can teach new concepts as well as entertain — but I like to use the word adventure. Illinois Issues September 1996 ¦ 29 |

||||||||||||||