|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

THE FOUR TOPS

WHEN IT COMES TO CAMPAIGN CASH,

ILLINOIS' LEGISLATIVE LEADERS

CALL THE SHOTS

analysis by James L. Merriner

An the bad old days, members of the Cook County contingent in the General Assembly were slaves to Boss Richard J. Daley.

Daley, the mayor of Chicago, controlled his subordinate Democrats by virtue of his power to slate them for public office and to hand out patronage jobs. Now and then, if a slated candidate faced a strong challenge, Daley would pour extra "walking around money" into his precinct workers' hands to help get out the vote on Election Day.

The upshot was that state legislators (and city aldermen) voted as Daley dictated, without a second thought. Even the nominal Republicans in the Chicago legislative delegation — elected under the "cumulative voting" system then in place — often were little more than an informal auxiliary of the Democratic Machine.

Thank goodness all of that is behind us now.

• The Illinois Act in Relation to Campaign Finance, passed during the Watergate-inspired reform efforts of 1974, put an end to secret special-interest payments to politicians by forcing disclosures of contributions.

• Daley died in 1976 and his son, the current Mayor Richard M. Daley, detests the "Boss" label. In any event, Chicago's dominance in the legislature is history.

• Court rulings in 1972, 1976, 1990 and 1996 restricted the use of patronage as a way for officeholders to reward their supporters.

• The Cutback Amendment of 1980, a citizens' initiative approved in a referendum, reduced the size of the Illinois House and got rid of "cumulative voting." Reformers argued the system of electing three House members per district strengthened Machine politics, that the Republicans were ringers.

And so the destruction of political bossism — the goal of progressive reformers in the United States for the past century — has been accomplished at last in Illinois.

Oh, yeah?

If you walked past the Capitol offices of the four General Assembly leaders last month, you might have guessed state workers were on a mass vacation. Hardly anyone was around.

16 / November 1996 Illinois Issues

That's because most top aides were on leave, working in the campaigns of favored candidates in selected legislative districts. In those races, it's the leaders who put up most of the money and call most of the shots.

In fact, the speaker of the House, the president of the Senate and the minority leaders of both chambers have become the new bosses of Illinois politics.

This is no longer just a matter of opinion among political pundits. Data compiled by the Illinois Campaign Finance Project, under the direction of Kent D. Redfield, political science professor at the University of Illinois at Springfield, have confirmed the financial and political dominance of those four leaders.

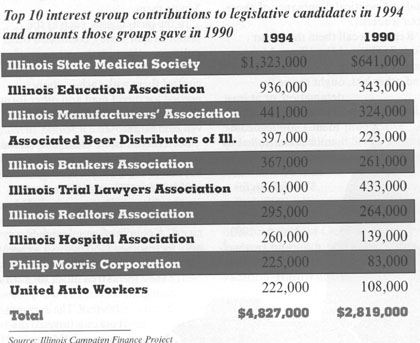

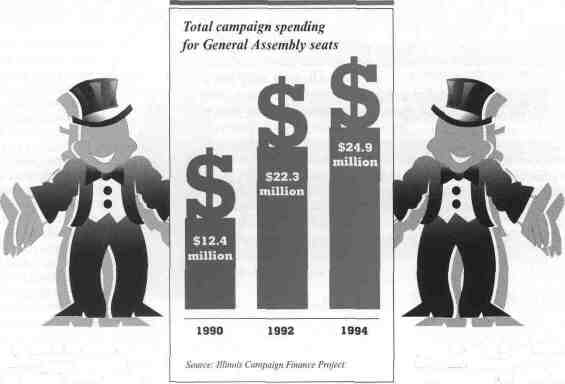

Reporters call them the "Four Tops." (The real Four Tops, Motown artists who sang "Can't Help Myself" and other hits, ought to sue for defamation, or at least trademark infringement.) Political committees controlled by Illinois' Four Tops raised a combined $7.1 million for the 1990 election cycle, $11.5 million for 1992 and an amazing $15.4 million for 1994, Redfield's research shows.

According to state disclosure filings, the leaders had a total of $10.3 million on hand as of June 30, 1996 — their version of "walking around money." They doubtless were occupied during the past four months raising and spending even more for the November 5 election.

The leaders' money is crucial in the relatively small number of targeted or swing districts that can determine which party will control the legislature. Redfield's research reveals that the leaders put up 55 percent of all the dollars spent in targeted House races in 1994, and 70 percent in targeted Senate races.

In the past, bosses, such as the senior Mayor Daley, controlled other politicians through the currency of slating and patronage. Today's bosses control them with cash — money needed for direct mail and other forms of advertising in modern, media-driven campaigns.

Secretary of State George Ryan was speaker of the last "big House" (1981-82) before the Cutback Amendment took effect. "The year I was elected speaker," he recalls, "we raised, I think, $325,000 [for GOP legislative races]. A couple of people signed a note for another $150,000. So we went in with less than $400,000. Today, they spend that much on a single district."

It's true. The average cost of a targeted district in 1994 was $3 80,000 for the House and $595,000 for the Senate, the Campaign Finance Project reports. "It isn't precinct work any more like it used to be," Ryan says. "A lot of [money] goes for direct mail. And cable TV is available."

In short, media campaigns have become so expensive that many General Assembly candidates are beholden to their party's legislative leaders for the money to run. The leaders in turn are beholden to the interest groups that bankroll their political action committees.

Former Gov. James R. Thompson — who incidentally left office with a million-dollar PAC, which, under Illinois law, he may disburse however he pleases — says, "Politicians spend more time raising money than they do anything else on this [top-ranking] level. That's demeaning, I think, to the politician and demeaning to the process. Money is too important in politics today. But there are no easy solutions for the dilemma that that poses."

Eighty-five percent of the Illinois electorate would agree with Thompson's concern that money has become "too important," a Campaign Finance Project poll shows. However, a facet of Thompson's own leadership style contributed to the hegemony of the Four Tops.

During his tenure as governor from 1977 through 1991, Thompson nearly always faced legislatures controlled by Democrats. The Republican governor liked to stage "summits," during which the five men would negotiate deals over state budgets and major bills. The Four Tops then told their members how to vote to consummate the deals.

These summits became so control-ling that most members — even the chairs of major committees — had little to do toward the close of legislative sessions beyond collecting their then-$77 per diem for expenses and 25-cents-per-mile travel allowance.

Once a budget deal was cut, the leaders hardly bothered to lobby members to vote for it. They assumed, correctly, that nearly everyone would vote as instructed and then go home.

Secretary Ryan also believes the Cutback Amendment, supposedly an instrument of reform, was a factor that eroded the independence of legislators.

Under the old system, each House district elected two members of one party and one member of the other

Illinois Issues November 1996 / 17

party. "I would like to see us get back to multi-member districts," Ryan says.

"When you had two Democrats and one Republican, or two Republicans and one Democrat, you could usually put some coalitions together to pass legislation that needed to be passed.

"Now, the leaders all raise their own money and do it on behalf of the institution [the House or Senate] or the party. It takes away an awful lot of independence from the members."

Patrick J. Quinn, the father of the Cutback Amendment, scoffs at this analysis. A former state treasurer, Quinn ran unsuccessfully against Ryan in 1994.

"The phenomenon of leadership contributions exists all over the country, not just in Illinois," Quinn says (a point also noted by Redfield). "And it exists in the Senate, which the cutback did not apply to."

In any case, a return to multi-member districts would do little if anything to lessen the costs of media-driven campaigns or the influence of interest groups.

For the past 15 years at least, with the skyrocketing expense of campaigning, the rise of summitry, and perhaps some unforeseen consequences of the Cutback Amendment, the four leaders have seized more and more of the tasks of recruiting candidates and running their campaigns. Interest groups were not slow to notice this and to pump up the leaders' treasuries.

Thus, when you punch your ballot card, you are not so much selecting a lawmaker, or even favoring his or her partisan or governmental philosophy, as choosing which set of interest groups will prevail.

To simplify crudely: If Republicans control the legislature, the Illinois State Medical Society, which poured cash into the two GOP leaders' PACs, gets its payoff in the form of limits on malpractice suits. If Democrats control the legislature, the Illinois Trial Lawyers, which poured cash into the two Democratic leaders' PACs, gets its payoff in the form of rejection of these limits, so-called "tort reform."

Among the most familiar cliches of modern politics are the disappearance of party discipline, the death of bossism and the resulting rise of the unslated, "free agent" candidates. Like any cliches, these are mostly true — and yet interesting mostly for the degree to which they are untrue. Somehow the absence of strong parties and old-fashioned bosses has not produced independent-minded public officials. Instead, it seems party discipline has evolved into a cult of personality — or, rather, a quartet of personalities; Senate President James "Pate" Philip, House Speaker Lee A. Daniels, Senate Minority Leader Emil Jones Jr. and House Minority Leader Michael J. Madigan.

What can we, or should we, do about this? The two touchstones of progressive reformers have always been "sunshine" and regulation. Reformers believe the public's business should be conducted in the open and that improper conduct can be minimized by regulatory limits.

The current enthusiasm of reformers is to find the best mix of disclosure rules and contribution and spending limits, with, perhaps, public financing, to "take the power of money out of politics," an ambition similar to wanting to take the necks off giraffes.

If it's more limits they want, current Illinois law certainly gives reformers a lot of room to work.

Illinois' 1974 campaign finance law imposed disclosure rules but no limits on contributions or spending. Only 15 other states lack caps on contributions, according to the Council of State Governments.

Many states place ceilings on donations from individuals or PACs, limit or prohibit donations from state-regulated industries (riverboat gambling, for example), or restrict transfers of politicians' campaign funds to other candidates or to their personal use. Twenty-three states offer partial public financing to candidates for various state offices or to political parties. Illinois has none of these features.

Further, the Illinois rules for disclosing campaign expenditures are vague. Hiring a private investigator to find dirt on an opponent, for example, can be hidden as "legal fees" or "consulting fees" (for evidence of the prevalence of this practice on a national scale, see Dirty Little Secrets, a new book by political scientist Larry J. Sabato and journalist Glenn R. Simpson).

In contrast, Illinois' rules for

18 / November 1996 Illinois Issues

inspecting the disclosure forms are onerous. To examine a candidate's financial report (the D-2 form), you must fill out another form (the D-3), listing your name, address, phone number, occupation and employer, and stating a reason for your audacity in presuming to look at a public official's public records. A copy of the D-3 then is forwarded to the candidate's political committee.

The Illinois system has remained basically unchanged for 22 years, largely because, many analysts believe, it tends to favor incumbents, who are unlikely to change the system that keeps them in office.

In 1985, lawmakers passed a bill to provide public funding for state political parties. In 1988, another bill would have provided public funding for candidates for governor. Both measures were vetoed by Thompson.

"I've never believed that government financing of campaigns, so that you don't have to raise money privately, is a satisfactory answer," Thompson said recently. "If [public] financing is equal, the edge is going to go with the incumbent. Sometimes the only way you can overcome the edge of incumbency is to raise and spend more money, right?"

While rejecting public financing, Thompson — like many persons interviewed for this analysis — offers no ready solution for the growing domination of politics by money.

However, polls are showing increasing public pressure for reforms.

With his usual thoroughness, Red-field has outlined The Pros and Cons: 38 Possible Options for Changing How Illinois Candidates Raise and Spend Money. The study was recently released by the Campaign Finance Project.

In summary, the options reviewed by Redfield include:

• Make few or no changes.

• Restrict contributions and/or expenditures.

• Provide partial public funding of campaigns, combined with contribution and spending restrictions.

• Provide partial public funding or other subsidies, such as free or reduced-cost campaign mailings and media exposure, or tax incentives for individual giving.

• Provide more "sunshine" by strengthening disclosure and enforcement.

A Campaign Finance Project task force, chaired by retiring U.S. Sen. Paul Simon and former Gov. William G. Stratton, has held meetings on the issue throughout the state. The project, supported by the Joyce Foundation and sponsored by Illinois Issues and the Institute for Public Affairs at the University of Illinois at Springfield, is set to conclude its deliberations November 15. The group's reform recommendations then will be released by the first of the year.

The Illinois campaign finance system hasn't been changed for 22 years, largely because analysts believe, it favors incumbents. favors incumbents.

The following suggestions represent the opinions of this writer and not necessarily those of the project or its sponsors. Here's the modest proposal: If the reform goal is not the grandiose one of taming the power of money but rather of abating the public's cynicism about politics, some tightening of disclosure and expenditure rules would be a promising start.

Donors now must list their names and addresses, but not their occupations or employers. (That's right, the politicians' D-2s are less stringent than the voters' D-3s.) Providing employers' names would curtail interest groups from disguising some of their collective contributions as individual contributions.

Under a practice known as "bundling," a lobby pools individual contributions from members of the same business firm, profession or union. The "bundler" picks up and delivers the individual checks to a politician, whose D-2 thereupon reflects individual, not PAC, donations.

On the expenditure side, candidates should identify all subcontractors and their activities. This would expose the private investigators now posing as consultants, the "push polls" smearing opponents as part of an ostensibly objective public opinion survey and payments made from "walking around money" dropped on ward heelers. Expenditures also should be restricted to the actual costs of running for office. Currently, political funds can be spent on just about anything. The Associated Press and Redfield have reported that Illinois lawmakers have dipped into their funds for such personal ¦ indulgences as buying a Porsche and paying for their children's college tuitions. The money legally can be converted to personal use as long as it is reported as income on tax returns.

And let's get rid of those ridiculous D-3s. Now the radical proposal. Some analysts have begun to challenge the value of sunshine and limits imposed for their own sake. For example, the assumption behind disclosing campaign donations is that voters then can decide whether, and by whom, a politician is controlled. Rockefeller Institute scholars Thomas L. Gais and Michael J. Malbin have written that this assumption itself rests on a dubious "causal chain."

To simplify the argument: Disclosure assumes that politicians will file accurate reports, that opinion leaders quickly can access and interpret the reports, that they then can convey the information to voters in a timely manner, that voters will assess that information in making their decisions and

Illinois Issues November 1996 / 19

that fear of such informed voters will compel candidates to clean up politics.

"If any of these steps fails, so does the whole chain," Gais and Malbin wrote.

In Illinois, it could be argued that every step fails.

Candidates' filings sometimes are late and incomplete. The regulatory agency (the State Board of Elections) lacks the authority and resources to enforce compliance effectively — or even to challenge improper expenditures. Filings are available only in Springfield and Chicago and, for the most part, only on paper or microfiche, not computers. Reporters' reviews of the filings normally get lost in the welter of election-season news. Disclosure has not yet purified Illinois politics.

Some of these defects could be fixed by passing bills to amplify the regulations and give the board some teeth. However, tinkering with the system is unlikely to undermine by much the power of big money — for example, money in the hands of the Four Tops.

Reformers' zeal for more regulations often simply inspires more ingenuity on the part of politicians to evade them. Still, repealing any provisions of the 1974 law is not among the "38 options" under consideration.

A truly radical reform would declare, in effect, death to individual contribution disclosures.

Anyone who gives more than $150 to any candidate must list his or her name and address. Even though reformers want to enhance public participation in politics, this provision has the effect of inhibiting participation by those who don't want their contributions made public.

In Chicago, public affairs consultant Larry Horist has formed a group to fight Mayor Daley's plan to convert the Meigs Field lakefront airstrip to a park. Horist shrewdly established it as an advocacy group, not a political committee, thereby evading disclosure rules.

"For God's sake, don't let Daley know I am giving you $5,000," Horist says some of his donors have exclaimed, reflecting fear of reprisals from the mayor's office.

The closest scrutinizers of the D-2s are not members of the public or the press but the politicians themselves. In particular, incumbents want to identify — and perhaps punish — their opponents' financial supporters. This is yet another way in which the system favors incumbency.

If the reporting standard raised the $ 150 floor by, say, a factor of 100 — to $15,000 — then individuals could contribute without fear of retaliation from political bosses.

Challengers would find it easier to raise money against incumbents. The concentration of money and power among the Four Tops would be, at least in part, dissolved.

William Marcy "Boss" Tweed of New York's old Tammany Hall, perhaps the original Boss, once said, "You may elect whichever candidate you please to office, if you allow me to select the candidates."

A generation of reform has yielded a system under which four top-ranking legislators in effect select the candidates in critically important districts. Maybe it's time for "anti- reform" — the elimination of burdensome individual disclosure rules.

James L. Merriner, who was the political writer for the Chicago Sun-Times, is the James Thurber writer in residence at Ohio State University. He is completing a biography of former U. S. Rep. Dan Rostenkowski. This analysis was funded by the Joyce Foundation.

20 / November 1996 Illinois Issues

|

Sam S. Manivong, Illinois Periodicals Online Coordinator Illinois Periodicals Online (IPO) is a digital imaging project at the Northern Illinois University Libraries funded by the Illinois State Library |