|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

Labor's comeback bid

by Steve Rhodes

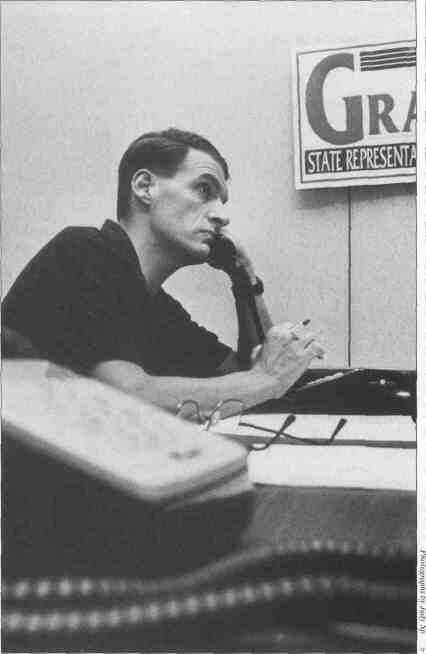

Brad Fralick, the state political and legislative director of the Service Employees International Union, helps make phone calls for Democratic legislative candidate Leslie Graves.

What a difference two years can make.

On the morning after the 1994 election, state AFL-CIO President Don Johnson faced a reckoning. Voters had installed the first Republican-controlled Congress in 40 years; here in Illinois, they had put the GOP in charge of the legislature and the governor's mansion for the first time in as many years. That was bad news for labor, which has traditionally supported a Democrat-backed economic and social agenda. Forgive Johnson if he thought the sun might not come up that November 9.

To say the nation's union leadership underwent a bout of soul-searching is to put it mildly. But, jarred into action by those election results and energized by a new national leader, labor has embarked on a political turnaround.

In Illinois, Johnson and his colleagues set about to analyze the results of the 1994 election and, believe it or not, they found the news wasn't all that grim.

The state AFL-CIO found that voters weren't rejecting labor; labor was rejecting voting. State union leadership discovered that 30 percent of its members who had voted in 1992 failed to vote in 1994, according to Johnson. "Labor didn't vote Republican. Labor didn't vote Democrat," Johnson says. "Labor didn't vote. They stayed home."

The problem, union leaders believe, was motivation, not a decline in support for labor's agenda. But galvanizing the rank and file became easier as Congress and the legislature swiftly approved policies opposed by labor. ¦ At the federal level, House Speaker Newt Gingrich and the GOP congres-

28 / November 1996 Illinois Issues

JARRED INTO ACTION BY THE 1994 ELECTIONS AND ENERGIZED

BY A NEW NATIONAL LEADER, LABOR HAS EMBARKED ON A

POLITICAL TURNAROUND

sional majority set about to rework a social contract that had been under construction since the Great Depression. In Illinois, meanwhile, the General Assembly launched its first post-election session by repealing an 88-year-old worker benefits law and initiating efforts to overhaul the state's workers compensation system.

"With what [has] happened since 1994 in the U.S. Congress and state legislatures, more people are cognizant of what's going on and what's being done to them," says Bill Looby, state AFL-CIO spokesman.

With a newly energized labor force, voter registration efforts by union locals, usually a chore, became easy going. "You generally have to fight with the leaders to get them to do it," Johnson says. "This year, they're calling us. There's a desire to do more."

Further, unions devoted additional resources to identifying their political friends and educating their members about issues, including the debate over the minimum wage, Social Security and funding for such agencies as the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

Nationwide, labor committed $35 million for issue-oriented advertising spots, aimed primarily at helping Democratic congressional candidates.

For now, of course, the vast majority of labor support in Illinois is going to Democrats. Of 150 endorsements in this election, the state AFL-CIO did support five Republicans: Robert Madigan, in the 45th state Senate District; Angelo Saviano in the 77th House District; Donald Moffitt in the 94th House District; Bill Black in the 105th House District; and Rita Garman in the 5th judicial district.

Nevertheless, union leadership worked in tandem with state Demcrats. On the eve of the AFL-CIO's endorsement session last summer, House Democratic Leader Michael Madigan offered practical political advice to campaign workers, including the best way to design a brochure and develop a "quotable message."

And nary a Republican was found among union-endorsed candidates in this state's congressional races. Union leaders focused their support where they have the most members: 77,000 in the 11th District, where unions backed Clem Balanoff against incumbent Jerry Weller; 64,000 in the 20th, where they backed Democrat Jay Hoffman against Republican John Shimkus: 60,000 in the 18th, where they supported Democrat Mike Curran against GOP incumbent Ray LaHood; and 50,000 in the 5th, where they supported Rod Blagojevich against Republican incumbent Michael Flanagan.

But it was in the legislative races — particularly in Chicago's south and southwest suburbs — where labor's efforts were most felt. Unions targeted three districts in particular: The 47th House District in the southwest suburbs, where Democrat Mark Pera challenged incumbent Republican Rep. Eileen Lyons (both are from Western Springs); the 80th House District in the south suburbs, where Democrat George Scully Jr. of Flossmoor challenged Republican Rep. Flora Ciarlo of Steger; and the Senate 40th District in the south suburbs, where Democrat Debbie DeFrancesco Halvorson of Crete challenged incumbent Republican Sen. Aldo DeAngelis of Olympia Fields.

Unions, which took on such typical campaign chores as phone banks and precinct walks, aggressively enlisted the help of their members.

Each local of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), for example, asked its members to sign a card pledging to spend five days (40 hours) doing political work this campaign season. Tom Balanoff, at SEIU 73 in Chicago, says he got 500 pledge cards back and estimated a thousand volunteers would get involved before Election Day.

That was the short-term strategy. For the long term, organized labor has returned to fundamentals: rebuild membership and create alliances. That double-barreled strategy is a direct result of new national leadership.

When he took over as head of the national AFL-CIO in October 1995, John J. Sweeney called for 100 activists in every congressional district in the country, political action training for all union field staff and an early endorsement of President Bill Clinton to ward off second thoughts about the man who pushed through the NAFTA trade agreement against labor's wishes. In fact, according to The Associated Press, one in four delegates to the Democratic National Convention last summer represented labor, more than 800 of them from AFL-CIO affiliates.

Influence in politics is rooted in such numbers. As the national head of SEIU, Sweeney was known for increasing membership, and he has brought the same evangelizing spirit to his new post. He has expanded union recruiting efforts beyond the traditional industrial workplace, pushed for new coalitions within and outside organized labor and crafted a political message on wages and safety designed

Illinois Issues November 1996 / 29

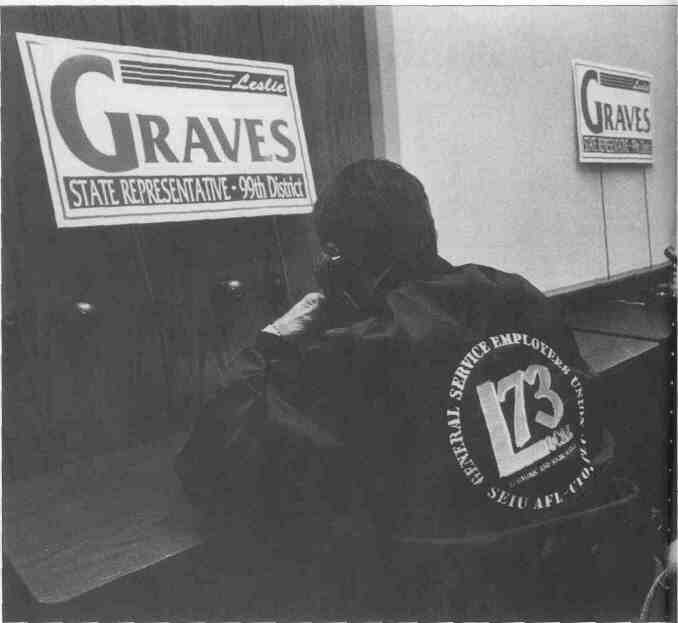

John Keating (left) and Michael Meiselmun work the phones for Democratic legislative candidate Leslie Graves of Springfield. Graves challenged incumbent Republican Rep. Raymond Poe in the 99th House District. The Springfield phone bank was run by representatives of several unions, as were other such operations throughout the state. Labor put on a big push this year for legislative candidates who support its agenda.

to appeal to all workers, union and nonunion.

Many union activists believe these changes were overdue.

Indeed, most analysts agree that labor's influence has been on the decline for the past couple of decades. They note that labor hasn't overcome some 15 years of anti-union sentiment, spurred in part by President Ronald Reagan's decision to fire striking air traffic controllers.

They also point to more recent losses: a series of "last stands" that include the Hormel strike in Austin, Minn., the long-running lockout of workers at A. E. Staley in Decatur and the strikes in that central Illinois city by workers at Caterpillar and Bridge - stone-Firestone. Further, they cite national policies they believe have weakened labor, including Congress' refusal to outlaw the use of permanent replacement workers in such disputes.

But labor has faced internal problems as well. As the nation's economy shifted from manufacturing to service industries, unions failed to recast their organizing strategies. And, in part because their leaders were flat-footed in their response to the changing economic environment, unions have suffered a 40-year decline in membership.

30 / November 1996 Illinois Issues

|

|

In 1995, membership stood at 14.9 percent of the work force (about 20 percent of the Illinois work force), compared to a high of 34.7 percent in 11954. Sweeney's drive to find new members has included appeals to the lowest-paid workers, previously shunned by many labor leaders. As a result, the face of organized labor has begun to change. Virtually all of the 8,000 janitors organized over the past several years in southern Calfornia, for example, are Hispanic and most of the newly organized health care workers throughout the country are women. But Sweeney also has moved to build coalitions among unions and with other groups. "Certain folks in labor have always felt that this is a fight we have to go at alone," says Joe Costigan, Chicago spokesman for the UNITE garment workers union. "The new leadership is basically saying we can't do this ourselves. We need allies. We need to look outside of our house. We have to stand side-by-side with more people who are like-minded." That lesson was reinforced in Decatur, where three unions spent nearly three years battling three companies over a range of issues, including pattern, or industry-wide bargaining, and the length of shifts. The AFL-CIO, still headed by Lane Kirkland, offered little initial support to the Decatur unions. Representatives of those unions resorted to crashing the annual AFL-CIO meeting in Bal Harbour, Fla., to get a hearing from their national leaders. And individual unions that were satisfied sat on the sidelines. It could well have been the low moment for organized labor. That dawned on Roger Gates, head of the Decatur rubber workers union, which struck Bridgestone-Firestone. "We didn't think it would ever come to our door. We had seen and heard of struggles across the country, but we isolated ourselves. But what affects the guy across the street affects you. We've come to the realization that if labor loses one battle, it will affect other people." Labor activists say learning that lesson is paying dividends now. "Unions in general are giving each other more solidarity and support than they have in the past," says Tom Balanoff of SEIU. Last summer's first "Union Summer" is an example of cross-union cooperation, and of the effort to build a long-term base. Union organizers were loaned among unions, which then recruited and divvied up college interns. The interns, who were paid $210 a week, were sent out to work in campaigns. They also were exposed to organizing strategies and labor history. |

But Sweeney's passion for coalition- building is resulting in the realization of another goal long sought by progressives: marrying labor to the fight for social justice. He has begun to build bridges with nonunion activists, including seniors (by joining with Save Our Security to take on the issue of Social Security), community groups (by supporting efforts to implement a "living wage" by A Community Organization On Reform Now) and religious groups (with the creation of the National Interfaith Committee for Worker Justice).

And, in an effort to give its message general appeal, unions launched a 28- city tour under the rubric, "America Needs A Raise," which positioned labor as representing all workers, not just union workers. The town-hall- style meetings occurred over the summer and included a stop in Chicago. That tactic took a page from the Republican strategy of 1994: the nationalizing of local elections behind a unified message.

More to the point, union leadership has focused on issues rather than candidates. In the past, labor leaders would tell their members which candidate to vote for, no questions asked. Now, they are trying to educate their members on the issues, and letting them take it from there. The final result is undoubtedly the same, but it may not always be, as the parties shift and third parties grow. It might mean some votes for a Ross Perot, or a Buchanan-like candidate who carries a labor-appealing economic message.

But the move also forces the Democrats to make an issues-oriented appeal to labor, as well as opening the door for Republicans to do so.

Whether labor can be given credit for winning any elections in Illinois this time around, Don Johnson is likely to have a brighter morning-after than he did two years ago.

Steve Rhodes, who lives in Chicago, writes for Newsweek and other publications. His previous article for Illinois Issues was about kids who become killers.

Illinois Issues November 1996 / 31

|

Sam S. Manivong, Illinois Periodicals Online Coordinator Illinois Periodicals Online (IPO) is a digital imaging project at the Northern Illinois University Libraries funded by the Illinois State Library |