|

LUST — Brownfields Update

By MICHAEL W. BAPPS, P.E. and RONALD R. DYE, C.P.G.

Governor Edgar Signs Lust, Brownfields Bills

The two most prominent environmental bills of the

1995 Illinois legislative session were recently signed into

law by Governor Jim Edgar. Senate Bill 721 provides

additional funding for underground tank cleanup and

House Bill 901 opens the door for risk-based environmental cleanups. Both bills deal with environmental

cleanups and, to some extent, both overlap one another.

And, each adds yet another layer of complication to an

already complex regulatory picture. Those affected by

the new statutes will find that there now exists a virtual

potpourri of cleanup options available for environmental remediation in Illinois. For those leaking underground storage tanks (LUSTs) reported prior to the

Illinois Pollution Control Board's September 15, 1994,

adoption of LUST rules (i.e., Part 732), tank owners

may now select from a menu of cleanup options that

can include the Illinois Environmental Protection

Agency's (IEPA) pre-rule standard, or Part 732 interim

standard (which is risk based), or risk-based guidelines

now under development by IEPA.

Two Masters

The Illinois LUST Fund, a state managed financial

vehicle for remediating leaking underground tanks, has

now run out of funds on two occasions. The first time

this occurred (1993), the legislature propped up the

Fund with $110 million generated through the sale of

bonds. By late 1994, the money had been spent and the

LUST Fund was in much the same shape that it had

been in the previous year. But, when the legislature was

unable to find additional funding in the Spring 1995

session, the Illinois program was placed at odds with

the federally mandated requirement for LUST financial assurance. With no relief in sight, USEPA reclaimed

the program, thereby imposing federal LUST rules on

Illinois tank owners to go along existing state LUST

statutes and regulations. At this writing, Illinois is subject to two sets of LUST regulations, and two sets of

LUST regulators.

Cleanup Wars

Because Illinois LUSTs are currently subject to joint

regulation by IEPA and its federal counterpart, you

may also throw into the aforementioned mix of cleanup

requirements and options, risk-based cleanup guidance

recently recommended by Region V of the United

States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). It

comes on the heels of yet another USEPA draft cleanup

guidance document, July 1994's Framework for Soil

Screening Levels (S.S.Ls). That document was nearly

coincident with publication of the Guide for Risk-Based Corrective Action (RBCA), earlier adopted as a

national standard by the highly respected American

Society for Testing and Materials. For those now insufficiently confused, consider also that for non-LUST

Brownfields, which in Illinois include pre-1974 LUST

incidents, the IEPA has been operating a voluntary

cleanup program since 1989, which program offers yet

another cleanup option. The Agency is now contemplating a proposed codification of pre-notice rules (as

Part 859) which, in early draft form, contain risk-based

cleanup options. A similar stand alone RBCA (pronounced Rebecca) Guidance Document has been circulated by IEPA for peer review, and is likely to be

proposed as a regulation that can jointly satisfy both

LUST and non-LUST (Brownfield) cleanup requirements.

Too Many Rules?

While the expense of environmental rulemaking

doubtless confuses both layman and non-layman alike,

the reader may take heart in that the moment may have

finally arrived in which nearly all of the partisans have

reached an accord. That there should be a risk-based

methodology for environmental cleanups is now a

generally accepted principle in Illinois. The current

regulatory confusion actually stems from a well intentioned patchwork of rulemaking and legislation,

spaced over several years, that has piled one partial

solution atop another, in the fashion of a tug-of-war.

This was born of a fundamental difference in philosophy which pitted IEPA's "old guard," and its rigid

single standard cleanup agenda, versus a national

movement by industry groups, as well as by USEPA,

aimed at customizing cleanups to fit circumstances and

need. In the end, the latter philosophy prevailed, due to

reoccurring shortfalls in cleanup money in the Illinois

LUST Fund. While recent legislation has fixed the

LUST funding crisis and made RBCA part of Illinois

statutes, the residual rules and statutes from the cleanup

wars remain on the books. As a result, the regulatory

landscape might now benefit less from the adoption of

new rules than from the repeal of the same old ones.

Senate Bill - 721 (LUST Funding)

SB-721, which initially dealt only with the subject of

convicted sex offenders, was used as a vehicle to secure

LUST funding in the fall veto session. With respect to

the latter purpose, it creates a new funding mechanism

that is expected to generate approximately $48 million

dollars per year during the next seven years. Funding

will be secured by imposition of a $60 per 7,500 gallon

tax on bulk fuel deliveries, to be passed on as a user fee.

It is estimated that this will equate to roughly 8-tenths of

a cent per gallon at the pump. Prior to adoption of

SB-721, LUST funding came from a 3-tenths of a cent

per gallon fuel tax, two-thirds of which is committed

for the long term repayment of the 1993 bond issue.

February 1996 / Illinois Municipal Review / Page 13

SB-721 is also intended to fix concerns raised by

USEPA that the Illinois LUST statutes and rules are less

stringent than federal requirements. That agency's

principal concern was that Illinois law allowed tank

owners to defer corrective action for LUST activities at

such times when the Illinois LUST Fund was depleted,

which generally describes much of the time of the

Fund's existence. Repeal of that provision was thought

necessary in order to clear the way for IEPA to regain

primacy over operation of the LUST program. Per

SB-721, new LUST regulations, that would correct various such matters, will need to be adopted by the Illinois

Pollution Control Board before January 1, 1997.

House Bill - 901 (Brownfields)

Approval of HB-901 came on the heels of the legislature's November 16,1995, acceptance of Governor Edgar's earlier amendatory veto of HB-544, the spring

session's "Brownfields" bill. The Edgar Administration

had disagreed with those provisions of HB-544 that

would have eliminated strict Joint and several liability

for all Illinois Brownfields. HB-901 served as a "trailer

bill" to the earlier vetoed legislation. It fixed the administration's concerns by providing for proportionate

shared liability for sites that enter the state Brownfields

program.

HB-901 creates Title XVII of the Illinois Environmental Protection Act, "Site Remediation Program,"

which establishes a quasi-privatization system for

Brownfields cleanup. In so doing, it identifies and defines roles for owner operators, cleanup contractors,

and oversight personnel. In addition, HB-901 introduces, as law, the concept of risk-based corrective action, and is explicit in setting forth that affected sites

must be evaluated using a three tiered "risk-based"

approach. Other HB-901 features are:

• HB-901 is not applicable to sites already regulated

under RCRA, CERCLA, or LUST rules or statutes. However, where applicable, such sites may

utilize risk-based corrective action procedures, to

the extent that they do not violate federal law and

regulations.

• HB-901 defines a Remediation Applicant (RA) as

the person performing the investigation or remediation.

• HB-901 defines the Review and Evaluation Licensed Professional Engineer (RELPE) as a licensed professional engineer contracted by an

RA, but who takes directions and work assignments from, and reports to, the IEPA.

• The goal of an RA is to obtain a "No Further

Action" (NFA) letter from the IEPA. The

Agency, with the assistance of the RELPE administers the site investigation and remediation programs.

• The required degree of site remediation can be

reduced through engineering, institutional, or legal controls such as restrict the current or future

land use, e.g., restrict residential use. However,

future changes in land use can be cause for the

retraction of an NFA.

• An RA is permitted to propose site specific

groundwater remediation objectives at levels that

exceed the IPCB's groundwater quality standards, i.e., an Agency approved variance.

• RAs receiving an NP'A must submit it to the applicable county recorder's office within 45 days of

receipt in order to make the NFA effective.

• HB-901 takes effect on July 1,1996. IEPA then has

until April 1,1997 to proposed applicable regulations to the IPCB, which is in turn required to

adopt final rules prior to January 1, 1998.

• A ten member Site Remediation Advisory Committee is created, appointed by the Governor,

comprised of seven members recommended by

industry, and three at large members appointed

by the Governor. The committee will provide

oversight of the statutes, rules, and operation and

activities thereunder, and make recommendations to the Governor, as appropriate.

Cleanup Standards

The traditional method for establishing standards in

the public health field, dating to at least the 1940s, has

been that of one size fits all. The sole recommended

health based drinking water standard for nitrates, for

example, has long been set at 10 milligrams of nitrates

(as nitrogen) per liter of water. Yet, nitrates represent

no known health threat to adults. The standard exists

only to protect infants, a relatively small portion of the

population. This is because infants are susceptible to

nitrate related methemoglobinemia (i.e., "blue baby"

syndrome). But, few would argue against enforcing this

standard in order to protect our most vulnerable. Such

standards are clearly appropriate. This is the traditional

model for setting health or aesthetic based standards

Page 14 / Illinois Municipal Review / February 1996

for air and water quality. First used in public health

agencies, the model was largely retained by successor

environmental agencies that formed in the 1970s and

1980s.

The general model for setting environmental standards is typically directed toward worst case scenarios

and applied "across the board." This is appropriate

when considering potable water or urban air quality.

And, certainly, from an administrative point of view, it

is far easier to enforce a single standard than one that

varies as to circumstances. But the health and aesthetic

based model begins to break down when it is applied to

environmental cleanups that do not directly relate to or

otherwise involve actual human exposure. In reference

to the earlier example, what should the soil cleanup

standard be set at for nitrates? There is no obvious

answer to this question. However, it is clear that to

cleanup soil nitrate levels to the 10 mg/1 drinking water

limit would certainly prevent the same soil from causing a nitrates exceedance in groundwater. Following

this line of reasoning, and independent of cost, a regulator can never err in approving a soil cleanup that is

taken to the lowest possible limit. This is the real story

behind the recent flurry of Illinois LUST and Brownfields legislation and rulemaking.

Edible Earth

In 1989, the Illinois legislature established a LUST

cleanup fund sustained by a motor fuel tax. When

created, the LUST fund was intended to pay for the

IEPA required cleanup of qualifying tank systems, subject to a $100,000 deductible. LUST cleanup standards

did not exist in the state at that time. But, in 1990, IEPA

established defacto soil cleanup standards for a set of

gasoline and fuel oil indicator compounds. For example, the cleanup objective for benzene, one of the most

common indicator compounds in gasoline, was set at 25

parts per billion (ppb). By way of analogy, a part per

billion is roughly equivalent to three seconds of time in

a century.

In 1991, IEPA tightened the earlier established soil

cleanup standards, lowering the cleanup requirement

for benzene, for example, from 25 ppb to 5 ppb. This is

a probable source of the often heard reference to "edible earth standards"; the drinking water standard for

benzene in Illinois is 5 ppb. At or about the same time

IEPA elevated the LUST cleanup standard, the legislature lowered the LUST fund deductible to $10,000 for

|

TABLE NO. 1

|

|

Illinois LUST Fund Disbursements

|

|

|

|

|

Gross Avg.

|

|

|

Funds

|

|

Dollars per

|

|

Year

|

Disbursed ($)

|

Claims Paid

|

Claim

|

|

1990

|

6,087,632

|

65

|

93,656

|

|

1991

|

14,499,974

|

223

|

65,022

|

|

1992

|

22,971,576

|

323

|

71,119

|

|

1993

|

40,693,392

|

792

|

51,380

|

|

1994

|

86,366,722

|

1,563

|

55,257

|

|

1995

|

5,331,666

|

81

|

65,823

|

|

Totals

|

175,950,962

|

3,047

|

57,746

|

|

most registered tank systems. The combination of these

two actions precipitated a frenzy of cleanup activity

that by year's end 1994 had tapped the LUST fund for

more than 170 million dollars.

Risk-Based Corrective Action

Cleanup expenditures in Illinois well exceed early

expectations of the rulemakers, as has the magnitude of

the problem. Illinois has more than 50,000 active and

registered underground storage tanks. And, from 1990

through year's end 1994, more than 12,000 LUST incidents (releases) were reported in the state. During the

same period, the Illinois LUST Fund distributed more

than 170 million dollars to cover fewer than 3000 claims,

with an average payout per claim of roughly $57,000.

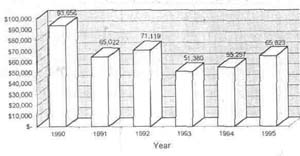

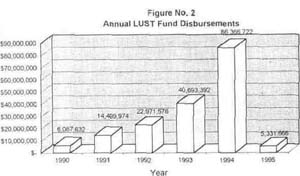

The record of annual disbursements from the LUST

Fund is itemized in Table No. 1 and illustrated in Figure

No. 1. Companion Figure No. 2 shows the steady rise in

annual disbursements followed by the precipitous drop

in disbursements that inspired SB-721.

|

A substantial portion of the claims were for partial

or ongoing tank closures. Some tank cleanups, particularly those involving groundwater remediation, are expected to continue for many years, and at a cost that is

yet unknown. However, annual disbursements from

the LUST fund are expected to remain relatively constant for the next seven years, probably not exceeding

an average of $50 million per year. Long term cleanups

such as groundwater pump and treat systems that might

require more than seven years for completion do not

presently have assurance for funding beyond that window of time.

Given its enormous expense, its limited success in

achieving full closure on LUST incidents, and the absence of a foreseeable end point, the legislature read-

Figure No. 1

Illinois LUST Fund Disbursements ($) per claim

|

|

February 1996 / Illinois Municipal Review / Page 15

dressed the state's LUST program in 1993 by enacting

House Bill 300. The linch pin of that bill was its focus on

eliminating expensive investigations and cleanups for

LUST sites that posed little or no apparent risk to human health and the environment. The statute set forth

geologic settings and other conditions to classify LUST

sites as a High Priority, a Low Priority, or No Further

Action, and directed the IPCB to adopt regulations

from which IEPA could administer the system.

Interim Cleanup Standards

On September 15,1994, the IPCB adopted the Part

732 "LUST Rules" (35 111. Adm. Code 732, Regulation

of Petroleum - Leaking Underground Storage Tanks)

which rely on an interim soil cleanup standard. At the

same time, the Board created a sub-docket for purposes

of establishing permanent cleanup objectives. The

Board conducted a status hearing on the matter of permanent LUST cleanup objectives on October 12,1995.

But, given the state of the LUST Fund, the USEPA

takeover of the LUST program, and pending legislation, the Board postponed work on the sub-docket indefinitely.

LUSTs at the Grass Roots

Today's LUST laws and regulations date back to

1984, when Congress enacted amendments to the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA). Home-owners and farmers are exempt from LUST regulations. However, the total number of schools, municipalities, and small business owners that must comply with

LUST laws well exceeds that of the major oil companies. So, unlike RCRA hazardous waste regulations,

which have had limited impact on most citizens, LUST

regulations hit at the grass roots level where they are felt

by local taxpayers and small businesses. This has probably made a difference in the outcome of LUST rule-making in Illinois. Whereas the hazardous waste lobby

might have had limited success in altering an environmental cleanup standard, stringent IEPA cleanup rules

applied at the local level probably aided in ushering in a

more economical risk-based cleanup approach. It also

helped to break up a major legislative log jam in the fall

veto session.

LUST Sites and Brownfields - The Future

Although rulemaking is incomplete, and while it

may take several years to pay down the accumulated

debt associated with old LUST projects, indications are

that LUST cleanups performed in the future will be

adequately financed. And, while pockets of resistance

doubtless remain, IEPA, as an organization, has come

to embrace the RBCA concept and has begun to approve risk-based cleanups. The Agency is soon expected to formally propose risk-based environmental

cleanup regulations that would apply to both LUST

and Brownfield corrective actions. The rules would

replace the interim risk-based cleanup formulae now

contained in the IPCB's Part 732 regulations. As earlier

alluded herein, most of those knowledgeable in the

subject will now agree that the accumulated statutes

and regulations that deal with LUSTs and Brownfields

tend to overlap, are, in some cases, obsolete, and under

any circumstance, could be safely consolidated and

simplified. It is unclear as to what group might step

forth to untangle the entanglements, although the Governor's Brownfields Advisory group is a best guess. •

MAY 3, 1996—

MAY 3, 1996—

PASSAGE DEADLINE

Michael W. Rapps, P.E., is president of Rapps Engineering &

Applied Science, a Springfield based consulting firm. Mr. Rapps

drafted the interim soil cleanup objectives contained in the IPCB's

Part 732 LUST Regulations. Mr. Rapps is also a peer reviewer for

IEPA's proposed Brownfield/LUST RBCA cleanup standards. Ronald Dye, C.P.G. is a professional geologist with Rapps Engineering.

Mr. Dye has experience with the investigation and remediation of

more than 200 Illinois LUSTs.

Page 16 / Illinois Municipal Review / February 1996

|