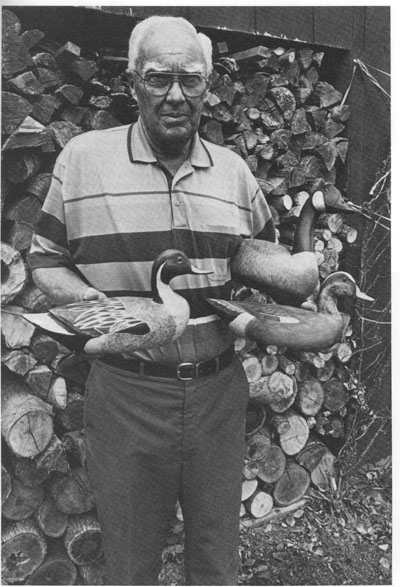

John Stotlar of Carbondale, a retired professor of physical education at Southern Illinois University, has been carving working wooden decoys for more than 30 years

OUR NATURAL RESOURCES

John Stotlar's art harkens to a day when hunters hunted over wooden decoys. For some waterfowlers today, that's still a hunting option.

BY DAVE AMBROSE

When I was a lot younger, waterfowlers used nothing but wooden decoys. And as you can imagine, carrying a couple of dozen of those life-sized decoys to a hunting blind could be quite a chore. Now days, waterfowlers tend to use more lightweight plastic decoys and plastic shells that stack and make carrying them a relatively easy task.

But there are still a few—very few, actually—carvers around who still make wooden working decoys, and one of those is Carbondale's John Stotlar. A retired professor of physical education at Southern Illinois University, Stotlar has been carving decoys for more than 30 years, and even he admits that he doesn't make many of the working birds any more.

"Just about all the decoys I used to carve were working decoys," Stotlar says. "But now days I make more of the decorative decoys than working ones. There's more interest in decorative decoys and you have to admit that it's a lot easier to carry plastic decoys to a blind than to lug around a bunch of wooden ones."

It's a lot cheaper, too. "You can go out and buy plastic gunning decoys for $5 to $10 each, while you might pay anywhere from $25 to $100 for a wooden decoy now days," Stotlar says. "But some hunters apparently like the nostalgia of hunting over wooden birds—maybe to help them remember the good old days of waterfowling—so I still make ones you can take out and use for hunting. I don't sell them by the half-dozen or dozen, like they did in the old days. I sell them one or two at a time or give them away."

I'd like to tell you that Stotlar got into carving duck decoys as a small boy because he couldn't afford to buy his own. That would have made a good story, but it wouldn't be true. It wasn't a monetary thing at all, and Stotlar was already an adult when he began carving. It wasn't an "urge to carve" that got him started either. It was more of a necessity than anything else. And he didn't begin by carving waterfowl decoys. He began by carving pigeon decoys.

"I was teaching at Southern Illinois University and was an avid waterfowl hunter," Stotlar says. "I used to like to go out and hunt pigeons during the off season to keep my shooting eye. I knew that pigeons decoyed really good, but I couldn't find any decoys that looked like pigeons, so I decided to try to carve some. They were terrible—the saddest looking things you've ever seen. My wife says they looked like blocks of wood with a pea-heads on them. But they worked."

Stotlar did about 75 pigeons—improving his carving with each bird. Then he turned his attention to waterfowl.

"I still hunt pigeons during the off-season, but I don't use any of my hand-carved decoys any more," he says. "I sold all but one of them when I found you could buy plastic pigeon decoys."

After pigeons, Stotlar turned his attention to waterfowl.

"The teal is kind of a specialized decoy," he says. "For a long time, no manufacturers made any teal decoys, so I carved two dozen teal decoys for myself, and found they worked pretty good. I always liked teal and I thought it would be kind of neat to hunt them over waterfowl decoys that I had carved."

And then he carved some buffleheads and gadwalls

42/ Illinois Parks and Recreation

|

|

John Stotlar of Carbondale, a retired professor of physical education at Southern Illinois University, has been carving working wooden decoys for more than 30 years |

43/ Illinois Parks and Recreation

"I will sell what I have on hand, but I won't just send them out when someone calls," says Stotlar. "I prefer that buyer's come by to see what they're getting. I don't want someone to order one and then be unhappy with what they receive."

and pintails and mallards and wood ducks and Canada geese.

"I guess I've carved just about every species you'll find around here except maybe ruddy ducks," Stotlar says. "I never could get the hang of carving those little ruddys."

And he carved working decoys, not decorative birds.

"I had a lot of people tell me I should carve decorative birds, but that just wasn't where my interest was," he says. "I carved working decoys, and I painted them to be used during the waterfowl seasons. I know my painting is poor, but it's good enough to fool ducks. Some of them are terribly poor and some are pretty good. But I don't worry about it. I do this for the relaxation and enjoyment it gives me, not for a second income. But when I think I've done a better-than average carving, I might send it out to someone who really knows how to paint a decoy and then I'll get about twice as much as I normally will get."

Picking up one of his working decoys, I detected a rattle coming from inside.

"Rice," he says. "When the old-timers carved hollow-bodies (working decoys), they always put a few grains of rice inside. If you could hear the rice rattle, the decoy was dry. If the decoy began taking water, the rice would become soft and the bird wouldn't rattle any more. That's how they could tell they needed to be re-sealed."

Stotlar tends to be more critical of his work than he needs to be. None of the decoys I saw would be classified as poor, and a great many of them were excellent. Harvey Pitt, one of the country's premier decoy collectors, agrees. He says Stotlar's work is increasing in value all the time.

"Some of his decoys are very, very good," Pitts says. "John has the capability of doing an excellent job. When he takes his time he turns out well-sculptured birds. They are superb. But he'll turn out some hogged-out gunners, too."

But while a collector like Pitt might not like to see the "hogged-out gunners," Stotlar seems to take a special delight in those birds. In fact, some are done that way on purpose.

"I'm not an artist," Stotlar says. "I don't worry if one of my decoys isn't perfect. I do this for the fun of it. If a piece of wood has a bad spot on it, I'll just carve around it, leaving the bad area on the decoy. It doesn't bother me. I like it. I think it gives the decoy character."

Because a lot of people like the look of old-time decoys, some of his "not so good" carvings are "aged" by putting them on the roof of his house for six to eight months.

"They weather' pretty quickly that way," he says. " "Then I take a few of them down to the Wildlife Refuge, where they are sold. But if someone comes in and is impressed with the '75-year-old' decoys, the owner makes sure the potential buyer knows the decoy isn't really old. I'm not out to fool buyers; we make sure they know the decoys were aged artificially."

The Wildlife Refuge is a Carbondale business that specializes in wildlife art, outdoor gifts and Orvis fly fishing equipment, and is the only place Stotlar uses to market his decoys. They sell six to eight of his decoys in a typical year, usually in the price range of $100 to $125. Stotlar sells other decoys from his home, with his only advertising being "word of mouth."

"I'm not worried if I sell a decoy or not," he says. "I sell a few of my decoys from my home and I also donate some of them to Ducks Unlimited banquets or other fund-raising events to be auctioned or given away as door prizes. I've probably given away more decoys than I've actually sold. I don't worry too much about it. I'm not in this to make a living; I just like to carve them."

And he's prolific. There are boxes of decoys in all stages of finish in his workshop. "I might turn out 10 to 15 bodies in rough form, then begin working on heads," he says. "Then I begin the task of finishing them up and either paint them or put a finish on them if they decorative birds."

It's pretty easy to tell whether you have a Stotlar decoy. He stamps his name and a number on the bottom of the tail of his decoys. He was nearing 1,600 decoys as this story was being written, but he admits the numbering system isn't completely accurate.

"I didn't start numbering the decoys from the very beginning," he says. "I try to keep a record of all the birds I've done, but sometimes I'll forget to number a bird and I don't always remember to advance the numbering system, so sometimes two birds get the same number. I'm not a stickler for detail, so I don't spend much time worrying about those sorts of things."

Stotlar also makes dove hunting boxes—boxes with a padded seat on top.

"They're made so you can store you shells and a cold drink inside, and sit while you wait for some doves to fly over," he says. "I make them for both adults and kids, and I've made more than 1,200 of these out of scrap lumber over the past 25 years. But I don't sell them. I give them away."

He had planned to quit carving several years ago when he got to 1,000 decoys, and even made sure his

44/ Illinois Parks and Recreation

two kids each received one of his "last" birds. But once he reached that magic number he realized he wasn't really ready to quit. That was about 600 decoys ago, and he still has no plans to end his carving.

"I did consider quitting one time a few years back," he says. "My wife and I went to a decoy show in Iowa, and after looking at the work of some of those carvers, I actually did quit carving for a couple of months. I figured I was nowhere close to being in those guys' league. But after awhile, I realized that I wasn't doing this for the same reason they were. They were doing it for the dollars they could make, and I was in it for the fun of it. So I picked up my knife and got back to carving."

Stotlar uses patterns he's found in books or has developed himself, and wood where he can find it.

|

John Stotlar uses a sender

to shape the head of a mallard

decoy he is carving. |

"I've carved decoys out of about every type of wood there is," he says. "I personally prefer red cedar for decorative birds, and I like to work with cypress, because it's easy to work with and doesn't rot as quickly as other woods. It used to be plentiful in southern Illinois, but is getting harder to find. My wife would like me to carve in walnut for the decorative birds, but it's too hard. I've carved a few birds out of cork, and that's the easiest wood of all to work with. A few years ago I got some 40-year-old western cedar telephone poles that I used to make Canada goose decoys from, but that's just about gone now. I have scraps of this and that. I just basically work with whatever wood I can get my hands on." Stotlar uses a band saw to cut the wood into the approximate shape, then works with a draw knife and small hatchet to refine the pattern. He also has a couple of sanding machines that gets him further along in developing the decoy. "Eventually though you get to the point where you have to pick up a knife do the more intricate work," Stotlar says. "The time I have in each decoys varies. It depends on whether it's going to be a decorative bird or a working decoy and the size of the decoy. If it's a working decoy, I don't have to cut or burn-in the individual feathers like I do with a decorative bird. And a Canada goose probably has 10 times more surface area than a teal, so it takes a lot longer to do. A big goose might take me 16 to 18 hours, while I can probably do a teal in about eight hours." |

With waterfowl season at hand as this story is being written, Stotlar will slow down on his carving and turn his attention to hunting. The 72-year-old hunter didn't get to hunt as often as he would have liked last year because his wife was ill. But he and his 88-year-old hunting partner were in the blind every day of the season for the two preceding seasons, and despite recent hip surgery, he plans to be in the blind for every day of this season as well.

The two of them have been hunting the same blind on the same small lake for a number of years. He prefers duck hunting over goose hunting, and likes to hunt puddle ducks more than divers. He says wood ducks are his favorite, but they don't stay around too long once cold weather arrives. He used the same over-and-under 12 gauge shotgun for about 45 years, but went to a newer gun when steel shot laws were enacted.

Does he still hunt over his carved decoys? "I used to hunt over carved decoys, but I use plastic ones now," he says. "I still have some of the old carved decoys I used to hunt over. They were pretty good decoys and I keep them around for sentimental reasons. But the plastic decoys are a lot easier to carry to the blind." •

DAVE AMBROSE is a staff writer for Outdoorillinois, a publication of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources. Reprinted from the January 1997 Outdoorillinois.

You can call Stotlar at his Corbondale residence to set up an appointment, 618.457.2989, or you con purchase his decoys at the Wildlife Refuge, a wildlife art store in Carbondale.

January/February 1997 /45

Macon County Conservation District Awarded Habitat Fund Orant

The Illinois Department of Natural Resources recently awarded the Macon County Conservation District a $75,000 matching grant from the Illinois Habitat Fund to acquire nearly 105 acres adjacent to the Friends Creek Regional Park near Argenta.

"This project will allow the conservation district to improve wildlife habitat and other natural resources at the park and protect it from encroaching residential development," said Brent Manning, director of the Department of Natural Resources. "Habitat preservation and management is the number one priority of the Illinois Habitat Fund. I applaud the Habitat Fund Advisory Committee for choosing such a worthy project."

The property, locally known as the Ankrom Addition Habitat Project, consists of about 54 acres of cropland and 51 acres of early successional timbered pasture. The conservation district plans to develop the site into a variety of different habitats including prairie grasslands, wetlands, bottom land and upland forests.

"The district is very excited about the great potential this property holds for habitat enhancement and expanded use of the Friends Creek Park by our visitors," said Paul Hagan, executive director, Macon Cty. Cons. Dist.

The Habitat Fund is derived from the sale of Illinois Habitat Stamps and associated artwork. Habitat Stamps, which cost $5, plus an issuing fee of 50 cents, are required of all hunters ages 16 and older, except those hunting waterfowl, coots or hand-reared birds on licensed hunting preserves and state pheas ant hunting areas. Nearly $1 million in Habitat Fund projects has been awarded by the Department since funding was first made available in 1994. Most projects include a cost-share element or in-kind services which greatly increase the return from awarded funds.

The Macon County Conservation District provided about $21,000 in cost-share funds toward acquisition of the Ankrom Addition and an additional $10,000 toward restoration seeding.

Applications for Habitat Fund projects can be obtained from any of the Department's district offices or by contacting the Division of WiIdlife Resources at 217.782.6384. Applications are due by Oct. 31 in the year preceding the anticipated funding date. •

Bike Path Grant Deadline March 3

The application period for the upcoming FY98 Illinois Bike Path Grant cycle is January 2 to March 3. Applications must be received by the Department of Natural Resources by the close of business (5:00 p.m.) on Monday, March 3.

A total of $3 million is expected to be available for allocation to local bike path projects. More than 400 miles of trails have been assisted to date by the program.

If your agency is planning to submit a project application, contact the Division of Grant Administration for an updated Bike Path manual. Keep in mind that a local public hearing is required for all applications that propose trail corridor acquisition and those development projects that initially introduce bike path construction in a linear greenway/ corridor. For an updated manual and other questions regarding the Bike Path program, contact: Illinois Department of Natural Resources, Division of Grant Administration, 524 S. 2nd Street, Room 315, Springfield, IL 62701-1787, 217.782.7481, 217.782. 9599 (fax). •

46/ Illinois Parks and Recreation

Internships for College Students

Application Deadline February 15

The Department of Natural Resources is offering college students internships in park management, park interpretation, park administration and forestry. The internships, which pay $1,000 per month, allow students to obtain practical experience and meet the hands-on training requirements necessary to earn their degree. Non-paid internships also are available.

The Department is seeking college students at the junior or senior level in natural resources related programs, including parks and recreation, ecology, natural resource management, forestry and grant administration. Preference will be given to applicants who need to complete an internship for their degree.

"In previous years, the Department has been very successful in obtaining highly qualified students to fill these internships," said DNR director Brent Manning. "Working with the universities has helped to find students who are willing to learn as well as work very hard."

The Department's Office of Land Management and Education is offering ten three-month internships, which will begin May 16 and end August 15, at sites throughout the state. The Department is also offering additional internships that begin in May and vary in length from four to six months at ten participating sites.

The Department's Division of Forest Resources is offering four internships in urban forestry and four in rural forestry. Interns for these paid summer positions will be assigned to one of four Department of Natural Resources' regional offices and may be assigned on a daily basis to a district forestry office within the region. An intern must be a full-time forestry student enrolled at a college or university at the junior, senior or graduate level and must have successfully completed a forest dendrology course.

Placement will be based on site availability and an applicant's area of interest. Interns will work full time and will be directly supervised by Department of Natural Resources' personnel.

Interested students should write to the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, Jeri L. Knaus, 524 S. Second St., Room 500, Springfield, IL 62701-1787, or phone 217.782.4963.The TDD number for hearing impaired is 217.782.9175. The application deadline is February 15.

The Departments Division of Wildlife Resources and Division of Fisheries also offers non-paid internships to college students pursuing degrees related to wildlife or fisheries

An intern will gain practical field experience by working under the supervision of a biologist or urban fishing coordinator at sites convenient to the student. Threemonth internships, available between midMay and September, will be arranged to accommodate a student's schedule. Preference will be given to junior, senior or postgraduate students whose major course of study requires an Internship. •

Governor Makes Appointments to Conservation Advisory Boards

Richard T. Wren of Oak Lawn and Debra A. Carey of Dixon have been appointed by Governor Jim Edgar to replace Vie Lindquist and Bonnie Noble on the Department of Natural Resources Advisory Board.

Wren is vice president of the International Union of Operating Engineers, Local 399, and Carey is a special projects coordinator for the Dixon Park District.

Reappointed to Advisory Board were Thomas P. Hester, Chicago; Arthur L. Janura, Inverness; and Benjamin A. Shepherd, Makanda.

Reappointed to the Illinois State Museum Board were: E Richard Ware, Jacksonville; Gerald W. Adelmann, Chicago; James C. Ballowe, Toulon; Lynn B. Foster, Highland Park; George M. Irwin, Quincy; Mary Ann MacLean, Libertyville; Gerry L. Suggs, Springfield; James A. Brown, Evanston.

Pennie J. Beattie of Lincolnshire was appointed to the Illinois Nature Preserves Commission.

Reappointed to the Illinois Endangered Species Protection Board were Judith D. Mendelson, Park Forest, and Darlene S. Fiske, Woodstock. New appointments to the board are John A. Clemetsen, Long Grove, and Michael A. Beebe, Flora.

Appointed to the Pollution Prevention Advisory Council were; Jay P. Koch, Woodlawn; James R. Foster, Springfield; and Clyde W Forrest, Urbana.

Theresa Cummings of Springfield was among eight people appointed to the Multicultural Services Committee.

Ted Flickinger of Springfield, executive director of the Illinois Association of Park Districts, was reappointed to the Governor's Physical Fitness and Sports Council. •

January/February 1997 /47

|

Sam S. Manivong, Illinois Periodicals Online Coordinator Illinois Periodicals Online (IPO) is a digital imaging project at the Northern Illinois University Libraries funded by the Illinois State Library |