Snapshots A POLITICAL PRIMER FOR THE PLANTING SEASON

As Illinois farmers get ready to head out to the fields, corn growers GLOBAL WARMING TREATY

States like Illinois by Toby Eckert It might be difficult to convince anyone who has lived through an Illinois winter that global warming is an imminent danger, though this year's relatively mild temperatures could give one pause. But back in December, international policy-makers in faraway Kyoto, Japan, brought the issue to the forefront for the entire world when they agreed to the first-ever limits on emissions of so-called greenhouse gases, the heat-trapping elements released by fossil-fuel burning industries, gas-guzzling cars and other energy-intensive entities. Many scientists believe the gases, primarily carbon dioxide, are putting an invisible blanket around the Earth that threatens climate changes of catastrophic proportions.

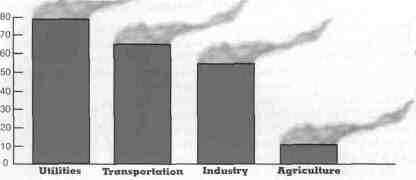

Convinced they have as much to lose from the treaty as their industrial counterparts, farm groups in Illinois and across the nation have joined the battle against congressional ratification of the treaty negotiated by the Clinton Administration. "We're very concerned about it, mainly because we're an energy-intensive industry," says Ron Warfield, president of the Illinois Farm Bureau. "It escalates our [production] costs and decreases net farm income. We believe that income drop would be very similar to what we had in the '80s." Indeed, agriculture directly produces about 11 million tons of greenhouse gases annually in Illinois, mostly nitrous oxide from nitrogen fertilizer and methane from animal waste, according to 1994 estimates by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, which is spearheading a task force examining the Kyoto treaty's potential impact on the state. That's about 4 percent of the total 277 million tons of greenhouse gases emitted in the state. The rest comes 28 / April 1998 Illinois Issues primarily from industries, electric utilities and highway travel. Based on expected increases in fuel taxes, curbs on nitrogen-based fertilizers and other costly steps that would be necessary to reform the nation's $500 billion fossil fuel economy, agricultural groups have predicted farm income drops of 24 percent to 46 percent. Farmers also fear losing market share to competitors in developing nations that, so far, aren't covered by the treaty and would be able to produce crops and livestock without the costly restrictions American farmers would face. "For production agriculture, we have no way to pass those increased costs along. We get what the market pays for our commodity," says Gregory Guenther, president of the Illinois Corn Growers Association. "Unless this is a truly global treaty, where everybody's on a level playing field, all the developed nations are going to be hurt." The Clinton Administration recently released an analysis predicting only modest increases in energy costs if the treaty is implemented. Gasoline prices would jump 4 to 6 cents a gallon. Electricity, fuel oil and natural gas costs would rise by 3 percent to 5 percent, according to projections. Bottom line, the report predicted a $7 billion to $12 billion increase in energy costs by 2012. However, critics noted the figures were based on several optimistic assumptions, including ratification of the treaty by developing nations. Some corn farmers see a silver lining in a potentially bigger market for ethanol, a corn-based gasoline blend that some research indicates may be less environmentally harmful than standard gas. Illinois farmers grow about half the corn used by the ethanol industry. But even that wouldn't make much difference, the farm groups say. A bigger ethanol market "is not going to offset the negative impact the treaty would have on the rest of our economy," Guenther says. Of course, farmers will lose if global warming is a reality. Parched crops won't do much to bolster farm income, either. "I think that, potentially, if the climate predictions are right, [global warming] could be an economic disaster for the state," says Jack Darin, Illinois field representative for the Sierra Club, an environmental group. "If the seasons get hotter and drier, you could see a farm economy of the future that is more like the Great Plains. That would be an economic shift unlike any other that has been felt in the state." To blunt such predictions, agriculture advocates play the trump card used by all opponents of the Kyoto treaty. "I think the scientific community remains divided" on whether global warming is a reality, Warfield says. "There's no clear consensus that global warming will take place or the impact that will have. There's certainly not clear evidence." Environmentalists counter that global warming skeptics are being increasingly marginalized in the scientific community. "There are some things that I don't think are in dispute by anybody: Temperatures are rising and there's a preponderance of evidence that greenhouse gases are responsible for it," Darin says. "To wait until there's absolute certainty would be to wait until it's too late to do anything about it." Politics, however, rarely follows the scientific method, especially when pocketbook issues are at stake. Few lawmakers have rushed to embrace the Kyoto treaty. Midwestern pols in particular, seldom noted for deep hues of green in their voting records, are unlikely to sacrifice economies back home on the altar of global environmentalism. Illinois' two Democratic U.S. senators, who otherwise show strong support for Clinton Administration initiatives, are decidedly cool to the treaty. Sen. Richard Durbin says he was profoundly disturbed by the environmental devastation he saw on a recent trip to China, which is expected to outstrip the United States in greenhouse gas emissions early in the next century. Yet China, India and other developing nations are not bound by the Kyoto limits. "You can't leave a country like China and not understand they have to be at the table if we're going to do anything on a global basis," Durbin

Major sources of greenhouse gas emissions in Illinois

These figures are 1994 estimates in tons. The 277 million total includes 43 million tons SOURCE: ILLINOIS DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Illinois Issues April 1998 / 29 says. "Our obvious long-term objective is to involve as many countries as possible in this treaty." Meanwhile, the White House has indicated it won't submit the treaty to the Senate for ratification until it can get nations like China on board. To start attacking the economic concerns, Clinton recently proposed spending $6.3 billion over the next five years to provide tax incentives for energy efficiency measures and to conduct research into new technologies that would cut greenhouse gas emissions. It will take a skillful combination of diplomacy and economics to make the world envisioned at Kyoto look like a friendly place for Illinois and the rest of the Carbon Belt, which just recovered from the economic dislocations of the past two decades. Karen Witter, who heads the state's Task Force on Global Climate Change, estimated Kyoto's cost to Illinois at $5 billion annually. "We're still trying to look at what the ramifications of this are. There are still some things under discussion," she says. "But there's no question that the types of reductions called for under the protocols would have a dramatic impact on Illinois." Toby Eckert, a former Statehouse reporter for the Peoria Journal Star, is a Washington correspondent for Copley News Service. ETHANOL AND ELECTIONS

Whatever its effects on the environment and the by Gayle Worland Three reasons Illinois may be able to keep its federal ethanol subsidy: Newt, ADM and Iowa. Illinois produces half the nation's ethanol, the corn-based alcohol fuel of "white lightning" fame that earns state corn growers up to $500 million a year. The subsidy, currently scheduled to end in 2000, goes to work right at the pump: Drivers who use gasoline blended with ethanol receive a 5.4-cents-per-gallon reduction in the 18.3-cent federal gas tax. The subsidy was meant to be a short-term incentive for alternative fuels. It goes to blenders, but its "ripple effect" has created an industry indirectly supporting more than 8,000 Illinois jobs. At the same time, it has cost the federal highway trust fund, which is fueled by gas taxes and finances road projects, more than $7 billion through 1995. Ethanol may be good economics in the Prairie State. Environmentally it's a mixed bag. The fuel is credited with reducing wintertime carbon monoxide levels in traffic-choked Chicago, where 95 percent of the gas sold contains 10 percent ethanol. A study just released by Argonne National Laboratory, and commissioned by the Illinois Department of Commerce and Community Affairs, maintains the current rate of ethanol use achieves net energy savings and reduces greenhouse gas emissions. But a 1997 report from the federal General Accounting Office argues ethanol also boosts summertime smog. Still, the fate of the alternative fuel may rest on something more esoteric: politics. Ethanol earns downstate votes as well as dollars, and is beloved by nearly all of Illinois' congressional delegation. U.S. Sen. Carol Moseley- Braun, who holds a seat on the Finance Committee — one of four in that chamber with jurisdiction over the massive $214 billion, six-year transportation bill pending in Congress — attached language to preserve the subsidy through 2007, while gradually lowering it from 5.4 cents to 5.1 cents a gallon. The subsidy faces opposition from Republican U.S. Rep. Bill Archer, the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee who hails from the oil-rich Lone Star State. But ethanol supporters have a formidable ally in the House: the speaker who would be president. Though Newt Gingrich's home state of Georgia lies miles from the Ethanol Belt, he recognizes the importance of the ag vote for his Midwestern GOP colleagues. And for himself. It doesn't hurt, of course, that Archer Daniels Midland Co., which runs ethanol plants in Decatur and Peoria, contributed more than $1 million to congressional and presidential candidates in the 1995-96 election cycle, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. Nor does it hurt that Iowa, another huge maize- producing state, is home to the quadrennial presidential caucus that separates viable presidential candidates from the chaff. But politics extends into home turf, as well. Illinois is also the nation's fourth-largest oil-refining state, and petroleum interests are fighting the federal ethanol tax break and a state subsidy that expires next year. "This subsidy was put in to help a fledgling industry get on its feet," says David Sykuta, executive director of the Illinois Petroleum Council. "Today, it's a multibillion-dollar industry, not exactly fledgling." While Moseley-Braun's ethanol proposal remains in the Senate transportation bill, that measure must be reconciled with the House bill, which contains no subsidy extension. But "I don't think there should be any great alarm, because we'll get it done," says U.S. Rep. Ray LaHood, a Peoria Republican whose own pro-subsidy amendment was axed in committee. Meanwhile, a farmer co-op is going ahead with plans to build a new ethanol plant near the northwestern Illinois town of Lena, and blueprints are on the drawing board for plants on the Kaskaskia River and in De Soto. near Carbondale, says Rodney Weinzieri, executive director of the Illinois Corn Growers Association. The new plants, he says, "won't survive without the federal tax credit. Period." Gayle Worland, a frequent contributor to Illinois Issues, is an online news producer and free-lance writer in Washington, D. C. 30 / April 1998 Illinois Issues THE ILLINOIS & MICHIGAN CANAL

An exhibit highlights the temporary by Alf Siewers The Illinois & Michigan Canal, which turns 150 this year, is today a modest strip of half-forgotten waterway, paralleled by bikeways for part of its 96-mile run from Chicago to LaSalle-Peru, and buried under the Stevenson Expressway at its east end. Yet it was this canal more than any other single monument to 19th- century industrial policy that turned Illinois into an agricultural powerhouse. It was to the rising American Midwest what the Suez Canal was to the British Empire: an economic lifeline, though in true American style a quickly disposable one. The democratic/industrial culture along its banks that helped create a nation was based in the rich Midwestern soil that Native Americans prepared with thousands of years of prairie fires.

In the process, a unique regional culture emerged in the canal towns that helped service the grain industry by providing raw materials and manufactured items for small farming communities, Chicago and international markets. Thornton Wilder once described the culture of the Great Lakes industrial belt as springing from an electrically charged strip of land stretching west from New York state south along the lakes to Chicago; its western extension and in some ways its headwaters were along the I&M. It was in this northern Illinois canal zone that the nascent Republican Party found its natural constituency: Cheers for Lincoln in his 1858 debate with Stephen Douglas in the canal town of Ottawa symbolized how the culture that helped create and was in turn shaped by the I&M would help transform the nation in the 1860s and afterward. The banks of the canal also saw the emergence of a free- thinking 19th-century Midwestern philanthropy, with nearby residents including the founder of the Boy Scouts of America, as well as a key sponsor for the introduction of East Asian philosophy into American intellectual life. It was in April 1848 that crowds in Chicago's Bridgeport (whose Irish political dynasty was another legacy of the canal) welcomed the canal's first boat, which cut what had been a three-week journey on foot across prairies to a 26-hour ride into the nation's agricultural heartland. Eventually outmoded by railroad lines, another manifestation of Whig industrial policy, the canal nevertheless proved its value by shipping millions of tons of grain and other materials. In more recent times, the canal has become the focus of efforts to preserve memories of the Midwestern culture that it helped to shape. In 1984, President Ronald Reagan signed a law establishing the I&M National Heritage Corridor, an effort to renew the canal zone's postindustrial landscape. This year, marking the canal's sesquicentennial, an exhibit called "Prairie Passage" by photographer Edward Ranney of contemporary and historic photos will run April 18 through June 28 at the Chicago Cultural Center. A series of lectures will also commemorate the canal's significance. Alf Siewers, a frequent Illinois Issues contributor, and a writer on cultural landscapes, helped with the editing of the exhibit book Prairie Passage, marking the canal's sesquicentennial with photos by Edward Ranney and essays by authors Tony Hiss and William Least-Heat Moon. Illinois Issues April 1998 / 31 |

||||||||||||||||||