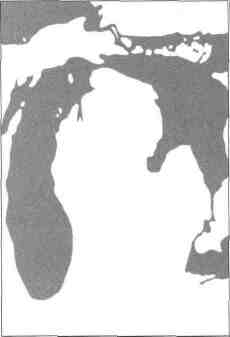

CLEANING UP THE GREAT LAKES

The author of a new book believes state and federal cooperation will help guard

the health of the Lakes. But our reviewer argues that's not nearly enough

Terence Kehoe

Published by Northern Illinois University Press. DeKalb, 1997

Review essay by Robert Kuhn McGregor

There is history, and then there is history.

It is a historical fact that the federal government assumed responsibility for antipollution efforts in the Great Lakes region back in the 1960s. Terence Kehoe very much wants you to care about that bit of information. Kehoe, a historian with the Ohio Historical Society, has written Cleaning Up the Great Lakes: From Cooperation to Confrontation, detailing the development in bureaucratic policy surrounding the Lakes. And he has done a very good job, getting the particulars just right.

It is also a fact that since the 19th century the Great Lakes have become a heavily used, heavily abused system of waterways. Somehow, I find that truth more deeply troubling.

Bureaucracy and its history may be important, but nature, and the need for fresh water, will forever be something more. Simply put, the Lakes mean something to people. After reading Kehoe's book, I recalled an old Jean Shepherd story. As long ago as the '50s, this irreverent radio comedian could wax nostalgic over lost scenes of his youth. Fondly, he recalled the waters near Gary, Ind., where he splashed happily as a child. Returning as an adult, he discovered they had been condemned. As a fire hazard.

But back to Kehoe. This is a difficult book to classify. On its face, the work seems to be an environmental history, a story of Americans facing up to their role in dirtying the five Great Lakes, and doing something to reverse the damage. To Kehoe, this most pivotal of truths seems almost by-the-way. He is not really interested in how the Lakes came to be polluted, or why, much less how sickening the mess became. Nor is he much attracted to studying the change in the human heart that created the modern environmental conscience. Rachel Carson and the Age of Ecology receive scant consideration; general public revulsion about urban-industrial use of the Lakes as handy sewers is peripheral. The near death of Lake Erie is just so much background noise.

Frankly, Cleaning Up the Great Lakes is little more than a history of petty bureaucratic infighting, a narrative of the power struggle among state and federal agencies as the national government assumed greater control of our daily lives. That the bureaucracies were struggling to see just who would clean up the Lakes, and how much, is entirely secondary to the author.

Kehoe is very precise in stating his intentions at the outset. He is interested in tracing the rise of federal power at the expense of state governments after World War II. He chose to study the Great Lakes states because their antipollution campaigns illustrate the nuances of larger policy struggles with the federal government. There are eight states sharing our northern coastline, each with its own history of pollution control. Add the various bodies representing city and county government, recall the powerful corporations resisting pollution control, and you have the kind of Byzantine maze of interests that make a policy historian's heart sing.

It is not the Lakes Terence Kehoe cares about, it is the welter of government and private entities. He wants to tell a story of competition for power; any site, any controversy with the same ingredients will do.

Shorn of its lavish and exacting detail, Kehoe's story is elegant in its simplicity. In the years following World War II, responsibility for clean water rested with the states. Public

26 ¦ November 1998 Illinois Issues

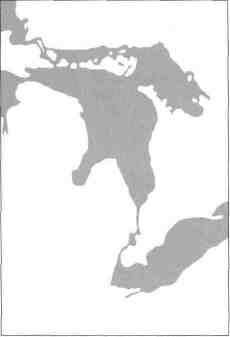

interest in the issue began with the century, when water's role in the spread of disease was fully grasped. Each state imposed some measure of control on dumping, focusing primarily on the flow of raw sewage into the Lakes. Industrial wastes were a secondary concern. But difficulties arose due to differences in standards from state to state: Indiana, for example, was far more lax than Illinois. While the city of Chicago undertook extensive efforts to reroute its sewage toward the Mississippi drainage to protect its fresh water in Lake Michigan, nine companies were dumping raw industrial effluent and sewage directly into the Grand Calumet River across the state border at Gary. Indiana did very little to interfere, raising the understandable ire of Chicago, and Illinois generally.

Disagreements among states called for federal intervention. But at the time, the Feds acted as little more than honest broker, chairing conferences where representatives from conflicting cities and states, and affected industries, hammered out differences. Kehoe discusses the process at length, under the rubric of "cooperative pragmatism."

Reading between the lines, pragmatism seems to have meant agreeing to do the absolute minimum to protect the Lakes' environments. Certainly concerns over algae blooms, swirling masses of indeterminate brown gunk and blazing rivers took a distant second to economic considerations. All a mill or refinery had to do was threaten a move to another state to make officials back off.

Reluctant though Kehoe is to admit it, what killed this cozy arrangement was water quality poor enough to provoke public outrage. By the 1960s, Lake Erie suffered from severely advanced eutrophication, with Lake Michigan not far behind. Fish and wildlife die-offs became too common, and several public beaches permanently closed. Moreover, the Lakes simply stank to high heaven. Citizens' groups, inspired by Rachel Carson's "jeremiad" (Kehoe's word), demanded firm and honest improvement.

Enter the federal government. The author rightly regards federal assumption of responsibility for national water quality a significant shift in public policy. With the states too often powerless to resist big industry or one another, a more powerful entity had to flex some muscle. To make regulation work, a consistent set of national standards maintained by a single agency was the only rational way to go. Hence

Illinois Issues November 1998 ¦ 27

the passage in 1969 of the national policy that created the Environmental Protection Agency.

Of course, no one was happy once the Feds took over. The states resented the loss of power; industry was shocked when the federal Environmental Protection Agency actually demanded strict water quality standards; cities howled that they could not afford the new sewage systems that suddenly became necessary. The U.S. government was unsympathetic: It sued when private and municipal polluters failed to clean up their act. Nevertheless, it failed to pony up the federal dollars promised to help right matters. Supported and often vociferously encouraged by an angry public, the federal environmental agency had little choice but to become combative. Cooperation gave way to confrontation,

The irony in all this is that the growth of federal power in environmental enforcement happened in an era when public distrust of government surged. What a delicious fact that it was none other than Richard Nixon who signed the environmental protection legislation into law. To Nixon, the environmental lobby was just one more bunch of flower children subverting the public trust, but it was too big to ignore. So while Americans became suspicious of federal activity in just about every other sphere, they demanded that it spearhead the effort to make people stop dirtying our Lakes.

Needless to say, the Feds did little to simplify the bureaucratic maze of environmental regulation. Terence Kehoe takes obvious pleasure tracking the confused welter of policy struggles among agencies and industries as the new regime settled in. Nor were improvements in water quality dramatic. Most polluters managed to miss a 1977 deadline to make improvements; very few got in much trouble. In the exhausted political climate of the Jimmy Carter years, it was enough to demonstrate a "good faith" effort to modify dumping practices.

Still, Kehoe argues, the quality of the Lakes did improve by the end of the 1970s. This is true. Despite arguments over how much phosphate to put in detergents, how much mine tailings to put in Lake Superior, how much raw sewage Cleveland could put into Lake Erie, things did get better. The algae became less noticeable, water returned to more natural colors, Niagara Falls ceased to resemble a sewer pipe, some beaches reopened. The author pats all those good policy- makers on the back, while grudgingly allowing there may be still a few more problems somewhere out there on the Lakes — agricultural chemicals and the like.

Of course there are more problems out there — severe ones. Kehoe does not acknowledge the current state of the 30 intractable toxic waste sites on the American side of the Lakes, many of them places he mentioned repeatedly in his overview of conditions way back when. Despite bureaucratic agonizing over Indiana's Grand Calumet River during the '50s (cooperative pragmatism) and through the '70s (public confrontation), the river is still in very bad shape in the late '90s. Because this is a policy history, rather than an environmental history, Kehoe sees fit to ignore such ongoing dangers.

Here is the book's most fundamental flaw. What Cleaning Up the Great Lakes lacks is passion, a sense that rendering one-fifth of the world's fresh water fetid and flammable is really a sin. Not a crime, not a policy problem for paper shufflers, but a mortal sin jeopardizing the national soul. One of my better students has described Kehoe's style as "detached"; it is difficult to conjure up a better adjective. Never once does the author betray that he might care, one way or the other. Historians are supposed to be objective, but we have also a duty to be morally suasive. Imagine a detached, objective and passionless tome treating the Holocaust, Indian removal or American slavery. No committed environmental historian could discuss what has happened to the Lakes so disinterestedly.

Even as a policy history, Terence Kehoe might have taken things a step further. After all, the growth of environmental consciousness since the early 1960s has confused some of the nation's most traditional political values. Throughout our history, Americans have held sacred the rights of contract and private property, the right to dispose of our own as we see fit. Throughout the 18th and much of the 19th century, the national government sought to turn our wealth of natural resources to private ownership as rapidly as possible. The assumption has been that our citizens are creative and energetic; left to their own devices, they would use the nation's resources to enrich the nation. That everyone has the right to go to Hell in his or her own fashion is deeply ingrained in the American consciousness.

More recently, it has become clear that in addition to being creative and energetic, we are also slobs who dirty our own nests. Unable to stop ourselves, we have turned to the national government to enforce a wholly different set of values: cooperation and cleanliness, costly though it may be. Environmental protection comes at the price of some individual freedom — there is no denying this. To promote our common welfare, it has become necessary to abrogate the sacred right of individuals to dump toxic wastes into Lake Michigan.

28 ¦ November 1998 Illinois Issues

Terence Kehoe does an excellent job of tracing the rise of federal power in the fight against pollution. The question is, has this development been an unalloyed good? I, for one, am not entirely sanguine envisioning a future of federal bureaucrats as the ultimate arbiters of environmental health. As Kehoe's book — again reading between the lines — makes clear, bureaucrats have their own agendas, often little connected to the policies they supposedly forward.

Kehoe, ever the policy man, argues in his conclusion that the New Federalism is the answer to this problem. State and federal governments must cooperate to implement environmental policy; they will keep an eye on one another. To my mind, this is not nearly enough. What forces governments to move is a concerned citizenry.

The public cannot sleep tight, secure in the knowledge that the Feds are guarding our Lakes. As environmental writer Edward Abbey observed, anyone who loves his country has to be prepared to oppose his government.

Terence Kehoe may be loathe to credit Rachel Carson, Earth Day and the environmental movement of the '60s with much influence, but that is the real reason environmental change came to the Great Lakes. People cared. Passionately.

For anyone who is concerned about the health of the Lakes, Terence Kehoe's Cleaning Up the Great Lakes is an important book, a detailed look at the shaping of a national policy. The work should not be the first or last word on the subject, however. Allow me to recommend two additional volumes; read all three, and you can say you know something about the environmental history of the region.

First, there is William Ashworth's The Late, Great Lakes: An Environmental History. Published in 1986, this is getting a bit dated. But Ashworth cares so deeply about the trashing of a region he obviously loves that the book becomes an impassioned plea for sanity. Speaking extensively in the first person, Ashworth conducts a chronological and personal tour of the Lakes, documenting the successive ravages of trappers, lumbermen, miners, fishermen, shippers and city officials. No one is left unscathed. And even after this long catalog of abuse, Ashworth believes the worst is yet to come. What happens, he asks, when the Plains farmers finally empty the Oglala Reservoir? What will they drain next, in their desperate desire for fresh water? Just guess.

More dull, but also offering a ray of hope, is Under RAPs: Toward Grass roots Ecological Democracy in the Great Lakes Basin, edited by John Hartig and Michael Zarull. Published in 1992, the book offers 11 case studies detailing cooperative community efforts to implement Remedial Action Plans (RAPs) to clean up the more troublesome toxic sites.

Some, such as Green Bay, Wis., have proven moderately successful. The problems there may serve as metaphor for the Lakes as a whole: Studies identify no fewer than nine severe environmental problems on the Fox River and on Green Bay itself. The task of coordinating the efforts of interested federal, state, county and city agencies might well prove daunting. In this case, a Citizens Action Committee comprising representatives from each agency, along with business representatives, independent technical experts and concerned citizens, has instead

The public cannot sleep tight, secure in the knowledge that the Feds are guarding our Lakes. As environmental writer Edward Abbey observed, anyone who loves his country has to be prepared to oppose his government. become a model of real accomplishment. Green Bay is still far from pristine, but it is returning to something resembling health.

However, at the opposite end of the spectrum, similar efforts in Gary, Ind., and Kalamazoo, Mich., have proceeded with agonizing torpor, their action committees scarcely off the ground. Overall, the tenor of Under RAPs suggests that government bureaucracy and grassroots democracy can achieve much through cooperation, though nothing is simple or guaranteed.

By supplementing Terence Kehoe's perspective with these books, the reader may nurture some appreciation of both the depths of our problems and the resilience of our determination to solve them.

There are real dangers, make no mistake. An overbearing federal government may be one of them, but only to the extent that it fails to achieve the task it has assumed. The greater danger is to watch an ongoing degradation of the Great Lakes, smugly assuming the federal government has matters under control. These are our Lakes, our responsibility. A government policy is not enough to save them.

Bob McGregor is an environmental historian at the University of Illinois at Springfield. His latest book is A Wider View of the Universe: Henry Thoreau's Study of Nature. He is at work on another book about the Great Lakes.

Illinois Issues November 1998 ¦ 29

|

Sam S. Manivong, Illinois Periodicals Online Coordinator Illinois Periodicals Online (IPO) is a digital imaging project at the Northern Illinois University Libraries funded by the Illinois State Library |