Foul-years ago, the Peoria Ballet nearly folded. Now attendance is up, the company has opened a second studio and its students are garnering national attention. It wasn't all luck.

CLARIFICATION A legal action filed by the Peoria Ballet Co. against Alfonso Figueroa regarding the issues referred to in the first paragraph and elsewhere in this article was dismissed by a Peoria circuit judge after the defendants responded that the complaint was "baseless and not grounded in fact." Figueroa denies all of the allegations made against him in the article.

It was 1994 and the darkest hour of the Peoria Ballet. The company had just lost its director of 10 years, Alfonso Figueroa. He had put the ballet $25,000 in debt and then fled with the computer and financial records. With no money coming in, the board, made up mostly of ballet parents, was on the verge of giving up. Instead, those parents passed the hat. Literally. They gathered in the cavernous studio and took in enough to keep the school open through that year.

The Peoria Ballet is not unusual in its struggle for support, both in cultural recognition and cold hard cash. But its challenge has arguably been greater than most. It took a politically powerful mentor, a determined board and a lucky break for them to get back on their toes.

The lucky break came first. Her name is Mary Price Boday. "Mary has clearly raised the bar here in central Illinois," says Alice McMahon, the ballet's new business manager who had to leave Broadway behind (where she performed onstage with actor Tony Randall) to move here for her husband's work.

McMahon recalls not expecting much when she walked into the old Grand Army of the Republic building — a brick fortress in downtown Peoria with a real cannon and cannonballs out front — where the ballet is housed. "But there was Mary, teaching. I remember thinking, 'She's really teaching. It's not the Dolly Dinkle Dance Studio.'"

Boday, who studied under Mikhail Baryshnikov's American teacher David Howard, and, indeed, has convinced Howard to come to Peoria as a guest instructor, is practically revered by those she teaches. Board member Tom Trerice's appreciation can be counted in the 120,000 miles he's logged on his car the last three years. Trerice drives from Bloomington to Peoria six, sometimes seven, times a week so his daughter Lauren, who turns 15 this month, can study at the Peoria Ballet. This, though Bloomington-Normal has its own school. "There is no comparison," says Trerice.

This summer, Trerice's daughter was among three of Boday's students chosen for a prestigious workshop with the Houston Ballet. "These kids competed [for those spots] with the best across the nation — kids from New York, L.A., Chicago, San Francisco — and they were right among the best of them. And, I'll tell you, a number of those kids in Houston were wanting to know where these [three] kids were getting their training."

To rebound financially, the Peoria Ballet first focused on increasing attendance. That has and always will be the core of the company's cash support. Boday used her contacts to draw in renowned guest artists at the same time the board came up with new ways of marketing performances. Last year, for instance, the ballet started a Nutcracker Ball, a dinner-performance package and silent auction.

Additionally, Boday has learned how to apply for grants. Not only did she not know how the Illinois Arts Council operated at first, but there were no records to guide her. Figueroa took them with him.

As recent as fiscal year 1996, the Peoria Ballet didn't receive any grants from the Illinois Arts Council. But since then, that support has grown significantly. In fiscal year 1997, the ballet received $2,200. In fiscal 1998, the grant nearly tripled to $6,050. And this fiscal year, that grant has more than doubled to $13,030.

This is leaps ahead of where the ballet was before the board stumbled across Boday. Beyond helping to bring the ballet back into the black — the board expects to retire its debt by year's end — admirers credit Boday with bringing ballet into the community. And, indeed, it is that, a strong marriage of cash and cultural support, that is the foundation of the Peoria Ballet's recovery.

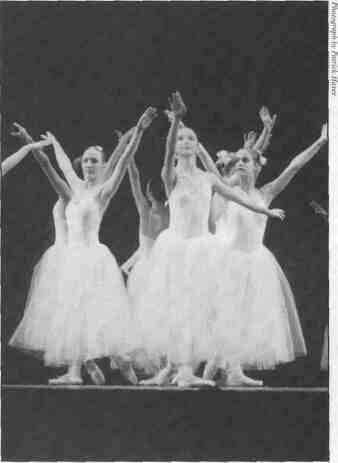

This May 8 will mark another milestone when the spring ballet. Swan Lake, is performed at the Peoria Civic Center with live orchestra. This is the first time the company has been able to move a performance from the smaller, cheaper Eastlight Theater across the river into the much larger arena — and to add live orchestra. McMahon literally paces in excitement.

"I want to marry the orchestra," she says. "And, in time, given how strongly we're coming about, maybe we will. Swan Lake is such a timeless classic — it's so beautiful. There's nothing like live ballet with live orchestra.

"It's hard to sell the arts. It's hard for people to understand how wonderful and beautiful, how ethereal the ballet is if they haven't experienced it."

"Public arts funding dropped in the '90s. It's going back up now," says Kassie Davis, executive director of the Illinois Arts Council, whose own budget rebounded with a $3.4 million increase this year. "I still think most arts organizations are not dependent on public money. The ability to get a lot of corporate money has also waxed and waned." Which means the trend has been to diversify the donor base.

24 / December 1998 Illinois Issues

Peoria was able to do that when then Mayor Jim Maloof joined the board and pushed to recruit others like him. He became the ballet's politically powerful spokesman, able with a letter to draw about 30 city leaders to a Caterpillar boardroom to view a video presentation of the ballet.

"I see Mayor Maloof as the turning point," says McMahon. He changed the makeup of the board from mostly parents, with obvious self-interests, to one balanced with business-minded city leaders. The new board "empowered me to market the ballet. Before, nobody was empowered to do anything." McMahon decided it was high time to fix up the ballet's office. A haphazard crew of volunteers and parents used to squeeze around piles of disorganized files in the tiny office. "It was awful. It's hard to believe now. We had plaster coming down on us. We had no lights — no lights. We had electricity, but the wiring was so bad, the lights didn't work." Now, the board takes responsibility for such things, says McMahon.

The Springfield Ballet learned this lesson long ago, says its company director Merle Shiftman. "We avoid [too many parents on the board] like the plague."

Bloomington-Normal's Twin Cities Ballet has a very small board — only six members. Terry Breen, general manager, would like to see two or three times that many people on the board. And, financially, things are tight as well. "Our fund-raisers haven't been real successful," says Breen, adding, "Five years back, we started doing school matinees and probably without those we wouldn't have survived." Those special performances, which aren't as long or as expensive, serve a dual purpose. Not only do they bring in much needed revenue, but they initiate the next generation to the importance of the arts, she says. Then, when that generation grows up, maybe they will be more supportive of the arts.

If not for Boday, the Peoria Ballet might be in an even more difficult situation than Twin Cities is today.

"I almost didn't take the job," says

Boday, who says it was the board's begging and the chance to remake the ballet which drew her. "We were not only talking about a company that didn't have any money, it didn't have any dancers either. They hadn't been trained. I knew I would be starting from scratch."

Foul-years ago, the Peoria Ballet nearly folded. Now attendance is

up, the company has opened a second studio and its students are

garnering national attention. It wasn't all luck.

Further complicating matters was the fact that Boday had already signed a short-term contract with a university in Pennsylvania. They compromised;

Boday brought in an assistant to run things daily while she commuted between the two states every three weeks for three days.

Money, obviously, was tight. The school brought in tuition, but ticket sales were down. Starting out, she paid for a lot out of her own pocket.

"I'd make all the long distance calls to bring in guest artists from my home, and then I'd have them stay with me."

Indeed, they still do. But in the last two years, the ballet has at least been able to reimburse Boday for feeding them. She also now gets paid for use of the costumes she brought with her from the ballet company she owned in Seattle, Mary and Friends.

Today, four years after what Trerice calls their dark age, the ballet has computerized. They've opened up a second studio. Their students are garnering national attention.

But, best of all, says Boday, the community is paying attention. Attendance is up. Further, current Peoria Mayor Lowell "Bud" Grieves supports starting what he calls a "United Way-like council for the arts," which would funnel donations, including some city money, to arts organizations like the Peoria Ballet.

Boday also would like to see the ballet move from the beautiful, if somewhat unconventional. Grand Army of the Republic building to someplace larger. Better yet, somewhere for the ballet, orchestra and symphony to be together. She has less grand goals too. She'd like the guest artists to be put up in a hotel.

"Always in this country, the arts have struggled. We have to help people develop an appreciation because, if we don't, we're just going to die in this country."

Jennifer Davis, a reporter for the Peoria Journal Star, was formerly a Statehouse bureau chief for Illinois Issues.

Illinois Issues December 1998 / 25