pause.

gasping machines scour the field in metallic splendor,

stone laid, concrete poured from spinning trucks

thick as grey porridge.

buildings constructed block upon block,

a child's wooden seat bolted to steel beams, forged into the earth.

pause.

faded gym-shoed feet approach the edge of an asphalt parking lot.

curious, a hopeful hand

lifts the corner of the roadway

like an adhesive bandage peeled from skinned-scabbed knee

all is dark and dead beneath, unhealed.

a voice asks

where is it...where did it go?

by Lee A. Hansen at age 16

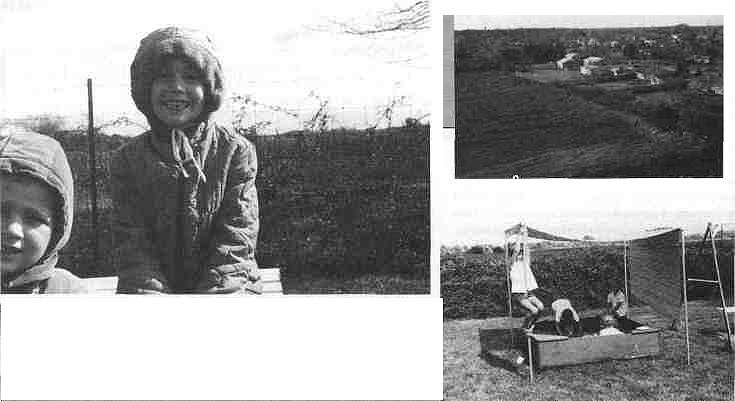

Photos on page 22: Lee A. Hansen's photographs from the family album; (top left) Lee and her brother Ty in1966 in their backyard with "The Field" just beyond the fence; (top right) Lee, Ty and friends play in the backyard near The Field, in 1967; (bottom) in 1971, remaining area of The Field as viewed from an 80-foot hill of soil created by earth movers.

22 ¦ Illinois Parks and Recreation

SPECIAL FOCUS

Where We Play and Who We Are

Children who explore forests, hunt insects and splash in streams, grow

up to be adults with an inherent commitment to the environment

BY LEE A. HANSEN

The summer of my sixth year my family moved to a modest home in the suburbs where our backyard opened out to more than 100 acres of cornfields. Later abandoned, the farmland reverted to an old field and was an ideal place for childhood adventure and discovery. I have memories of searching for hidden softballs in the tall weeds, watching winter pheasants approach our yard for feed corn while I shivered in a large cardboard box equipped with a peephole, chasing through fields of flowers and decaying corn stalks after prized tiger swallowtail butterflies, and riding my bike on well-worn paths through what we came to call "The Field."

Then when I was 16,1 sat in the comfortable and secure branches of a large silver poplar in our backyard as a parade of earth movers noisily made their entrance onto The Field. Watching from my perch in the poplar, as the landscape was forever changed to make way for an extensive shopping mall, I wrote a poem (see page 22) mourning the loss of the place where I had spent countless hours playing—a place I had come to know and love as a child.

It is highly likely that my exposure to the life and natural wonders in the field just beyond my childhood backyard helped shape the person I am today. Psychologists, teachers and naturalists studying the effects of childhood experiences on adults are discovering a direct link between contact with natural places as children and commitment to the environment as adults. In formal studies of environmental activists, Kentucky State University professor Louise Chawla writes that "most respondents attributed their commitment to a combination of two sources: many hours spent outdoors in a keenly remembered wild or semi-wild place in childhood or adolescence, and an adult who taught respect for nature."

Not all childhood experiences in natural areas lead to environmental careers. While recently serving jury duty, I spoke with a fellow juror—who I learned was a very successful salesman—about his love for the outdoors and how he visited different nature centers with his children and share with them his enthusiasm for the natural world. After three days and quite by accident, we discovered that we had grown up in the same neighborhood and had spent our youth playing in the same wild field. Though his adventures in The Field did not lead him on the same career path as me, they helped form the basic groundwork for his current enjoyment of the outdoors.

In The Thunder Tree, Robert Michael Pyle writes that he believes "most people have a ditch somewhere —or a creek, meadow, woodlot, or marsh....

March/April 1998 ¦ 23

SPECIAL FOCUS

Those who contemplate the beauty of the earth find reserves of strength that will endure as long as life lasts.

These are places of initiation, where the borders between ourselves and other creatures break down, where the earth gets under our nails and a sense of place gets under our skin."

Will Nixon, author of the article "How Nature Shapes Childhood," says he roamed "a swampy scrap of woods that was our shortcut to school... these small woods had planted the original pleasures that I now enjoy each time I hike in a protected forest, watch for birds in a marsh, or come home with a pocketful of pine cones that I try to identify in a field guide."

Nixon explains Professor Chawla's findings further, summarizing that "...whether or not they become naturalists, most children like the outdoors. Studies have found that they actually spend less than 15 percent of their time in natural places, but they count their neighborhood woods, fields, forgotten lots, and waterways among their favorite spots."

The contribution to the development of future environmental activists notwithstanding, contact with the natural world is thought by many to be an ever important element in child development.

"By forging connections with plants, animals, and land, by finding ways to experience some relationship to the Earth, individuals can gain a sense of worth. Herein lies security," writes Stephen Trimble in The Geography of Childhood. "The natural world does not judge. One route to self-esteem, particularly for shy or undervalued children, lies in the out-of-doors....The sun, the wind, the frogs, and the trees can reassure and strengthen and energize."

In her book The Sense of Wonder, Rachel Carson describes exploring the shoreline and a small tract of woodland in Maine with her young nephew:

"Is the exploration of the natural world just a pleasant way to pass the golden hours of childhood or is there something deeper?

"I am sure there is something much deeper, something lasting and significant. Those who dwell, as scientists or laymen, among the beauties and mysteries of the earth are never alone or weary of life. Those who contemplate the beauty of the earth find reserves of strength that will endure as long as life lasts."

Those who work in the fields of nature education share a similar conviction. In Earth Education... A New Beginning, Steve Van Matre asserts that the primary purpose of the Institute for Earth Education is to help people develop a better sense of relationship with the natural world.

"Improving upon this personal contact and connection lies at the heart of everything we do," says Van Matre. "We believe many people have become estranged from the places and processes that actually support their lives. Thus helping them restore a harmonious and joyous relationship with the earth is our most important task."

"Perhaps we can not statistically prove that people who are more connected to the earth are wiser and healthier and happier, but common sense tells us that it must be so...without lots of firsthand experience with the natural world people grow up just as deprived as children without nutrition."

Contact with the natural world as a child is considered by some to be critical to our personality development. As early as 1959, Harold Searles suggests that "the nonhuman environment... constitutes one of the most basically important ingredients of psychological existence."

Natural places offer children freedom from parents and from an indoor world "bound by rules of order, neatness, propriety," writes Chawla.

24 ¦ Illinois Parks and Recreation

WHERE WE PLAY AND WHO WE ARE

Some researchers believe that children that miss out on their "earth period" or "bug period" may be losing a critical chance to bond with nature.

Nixon summarizes: "The years of middle childhood, in which so many children have traditionally roamed their local swamps, woods, creeks, and other natural places in search of whatever fascinates them.

"Moreover, as children explore the freedom and rich trove of discoveries afforded by natural places, and as they create their own worlds and adventures separate from the indoor worlds created by adults, they may progress through important stages in their intellectual and emotional development."

Several barriers exist, however, to providing children with opportunities for repeated experiences in natural places. Not only are natural areas and open spaces rare commodities in cities and urban areas, but even in the suburbs, many of the forests, fields, marshes and empty lots that children roamed a generation ago have now disappeared under housing developments, parking lots, business courts and shopping malls. In many cases, the opportunity to spend time in a special natural place simply does not exist because the natural places no longer exist.

Additionally, "American children's free-wheeling play once took place in rural fields and city streets, using equipment largely of their own making," writes Richard Louv in his bestseller Childhood's Future, quoting Professor Brian Sutton-Smith of the University of Pennsylvania.

"Today, play is increasingly confined to our backyards, basements, playrooms and bedrooms, and derives much of its content from video games, television dramas and Saturday morning cartoons."

According to Gary Paul Nabhan in The Geography of Childhood, "The percentage of children who have frequent exposure to wildlands and to other, undomesticated species is smaller than ever before in human history."

And what children do know about the natural world is increasingly gleaned from the Discovery Channel and public television.

What does this mean for the field of parks and recreation? In an era of vanishing open space and as the primary stewards of public natural areas in most communities, it is imperative that park and forest preserve districts continue to provide safe, natural places for children to play and explore, frolic and grow. Expanding and adding to these types of holdings will provide even more children the opportunity to get in touch with nature and spend time outdoors.

But our responsibilities as park and recreation agencies go further, because even when the natural places are close at hand, children in our day and age are interacting less and less with the world outdoors. As a result, providing program opportunities that involve and immerse children in nature—and on a repeated basis—is essential to helping them develop a relationship with natural places and, therefore, essential in helping them develop into healthier and happier adults.

LEE A. HANSEN

is the Nature Center supervisor for the Skokie Park District.

Further Reading

Baylor, Byrd. Your Own Best Secret Place. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1979.

Carson, Rachel. The Sense of Wonder. New York: Harper & Row, 1956 and 1984.

Louv, Richard. Childhood's Future. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1990.

Nabhan, Gary Paul and Stephen Trimble. The Geography of Childhood. Boston: Beacon

Press Books, 1994.

Nixon, Will. "How Nature Shapes Childhood." The Amicus Journal, vol. 19, no. 2 & 3. Pyle, Robert Michael. The Thunder Tree: Lessons from an Urban Wildland. Boston:

Houghton Mifflin, 1993. Van Matre, Steve. Earth Education...A New Beginning. Warrenville, Ill.: The Institute for Earth Education, 1990.

March/April 1998 ¦ 25