|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Louise A. N. Kerr Chicago's Saint Francis Wildcats were organized as a sports club in the mid-1930s by young men of Saint Francis Parish. It was the west side church home for more than a third of the Mexicans who began arriving in large numbers in Chicago during and after World War I. Today, after more than sixty years, the "Wildcats" continue to meet and sponsor several charitable events each year for the benefit of the Latino, Mexican, and Mexican American communities in Chicago. At their annual banquet, which now draws more than seven hundred including children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, and hundreds of admirers and friends, the Wildcats proudly wear distinctive maroon blazers to identify themselves. For the most part they are retired now, many having moved to Los Angeles, Phoenix, Guadalajara, and other warm climes, where they still faithfully gather to talk about the Latino Chicago they shared. Better than almost anyone, the Wildcats know the history of Latinos in Chicago, which they helped to develop and in which they continue to be active participants. That history began before the turn of the twentieth century when a few Mexicans and other Latin Americans came to Chicago, primarily as itinerants and entertainers. A few settled. But the first large groups of Latino immigrants to Chicago and the midwest were Mexicans who arrived as contract workers to replace soldiers and European ethnic workers during World War I. These earliest immigrants quickly congregated in neighborhoods surrounding the industries that recruited them: South Chicago amid the steel mills; Back of the Yards near the meatpacking houses; and the Near West Side-Hull House area close to vast railroad networks and light industries like candymaking and clothing manufacture. Until the early 1920s most new Mexican migrants to the city were single young men, but by the end of the decade the number of Mexicans had grown to almost 20,000, one-third of whom were, by then, women, children, and other family members. Manuel Gamio, a Mexican sociologist conducting research for the Social Science Research Council, and Paul S. Taylor, a young University of California economist, first told of the Mexican Chicago. They discovered the several vibrant, growing, and rapidly established settlements, and chronicled the development of political, religious, and other cultural institutions and social networks which showed, despite some discrimination and economic hardship, Mexicans' rapid adaptation to long-established neighbhorhood practices of ethnic competition and succession. Like immigrants who had preceded them, many of the newly arrived immigrants maintained strong ties to the Mexican homeland, conveying news in often short-lived newspapers, sponsoring rallies for competing candidates for the Mexican presidency, and, very early on, hosting celebrations of Mexican Independence and Cinco de Mayo (Mexicans celebrate the May 5, 1862, defeat and ouster of the

62

French from Mexico). By 1929 Chicago was known to emigrating Mexicans as the largest colonial outpost outside the Southwest. Strong Mexican and Mexican-American sensibilities had been affirmed. And, while Chicago's Mexican and Latino population was still quite small, migration patterns demonstrated that the Midwest already had become a major magnet for Mexican migration, and Chicago was the destination that most emigrants cited. Like most Chicagoans, Mexicans in the city suffered unemployment and severe economic hardship during the Great Depression. Almost a third were unemployed by 1932. Both the Mexican and United States federal governments sponsored repatriation drives to supplement the efforts of local governments and charities. Thousands of indigent immigrants from Italy, Poland, Mexico, and elsewhere either chose or were directed to accept repatriation if they could not support themselves. Without question, proportionately more Mexicans were indigent and repatriated from Chicago than other ethnics. Like Ignacio Romero, Jr. they were detained, harrassed, and bullied by relief officials who were " determined to rid the city of them. "But they seem to have been less harshly treated than Mexicans in some parts of the Southwest. In any case, by the end of the decade the number of Mexicans in Chicago had declined to as few as 14,000. On the eve of World War II the number had risen slightly to almost 16,000, including many American-born children of the early immigrants. The pioneer settlements had begun to take on identities that simultaneously conformed to socio-economic circumstances of the south side neighborhoods, the ethos of the industries supporting those neighborhoods, and the leadership of the Mexican settlers. By the end of the decade, those who had come in the first wave of immigration were more "American" than "Mexican." South Chicago, for example, was supported by both the strength of the steel industry and of the unions that were forming in the 1930s. Latinos in South Chicago were solidly working class and mostly segregated ethnically as the neighborhood always had been. By the early 1940s Mexicans in South Chicago, very important in the organization of the United Steel Workers, were dues-paying union members whose children aspired to follow their fathers and uncles into well-paying jobs in the steel mills. Ethnic tensions between Mexicans and Poles and Blacks remained, but the clashes of the 1920s had settled into routine relationships on the job and in the neighborhood, where most social activities were still predominantly ethnic, in this case, increasingly Mexican American. Almost all Latinos and others in Back of the Yards earned their living in the meatpacking industry. Dimensions of community among these Latinos had been much slower to develop for a variety of reasons. No Latino church emerged in the neighborhood until 1945; parishioners either attended Our Lady of Guadalupe on the south side, Saint Francis further north, or they were served by missionaries from those churches in local storefronts. Ethnic identities were as strong in Back of the Yards in the 1930s as they had been when Upton Sinclair wrote The Jungle at the turn of the century. But because no one group held a majority, it was no coincidence that along with the unionization of packinghouse workers the major neighborhood organization effort went into the formation of Saul Alinsky's Back of the Yard Neighborhood Council. It was an inter-faith, inter-ethnic coalition of neighborhood groups that served as a bridge among the residents and workers, including Mexicans. The Near West Side, especially around Jane Addams' historic Hull House, was for Latinos at once both economically eclectic and ethnically homogeneous. Historically an important port of entry for immigrants, by the time Mexicans had arrived, the neighborhood had become predominantly Italian, with some Greeks living in the north end and a few Jews remaining in the Maxwell Street area. A smattering of long-time Germans and Irish could also still be found in the neighborhood. Mexicans congregated primarily along Halsted south of Hull House. When World War II began, the street increasingly housed businesses catering to the Mexican settlement. St. Francis of Assisi, originally a German parish, served as the heart of the settlement with its parish school, short-lived gymnasium, and the nearby Cordi-Marian nuns. It was here that the Wildcats came together in the mid-1930s, at first only to sponsor neighborhood athletic teams for boys and girls. During the war most of the Wildcats

63

joined the military, and the neighborhoods, especially the Near West Side, wholeheartedly supported the patriotic efforts of local heroes like Manuel Perez, a paratrooper who was killed in the Philippines and posthumously became Chicago's first Latino Congressional Medal of Honor winner. Those left behind published a local newsletter for the servicemen throughout the war chronicling the daily comings and goings of neighbors. In turn, the boys at the front sent homesick letters to be printed. Many Wildcats, like Charles Galvan, never came home, and they became the inspiration for a variety of political and civil rights efforts during the 1950s. The newsletter also revealed changes in the neighborhood. For example, the loss of men to military service increased the need for defense workers. From 1942 onward contract workers were brought to Chicago to work primarily as railroad track laborers but found their way to other industries as well. Braceros, who worked predominately as agricultural workers in the southwest, were housed in the Mexican settlements, especially in the Near West Side where they intermingled with long-time residents, and, in some instances married local girls. In addition, other Mexican American newcomers to the neighborhoods were arriving in increasing numbers from the Southwest. Many of the newcomers by passed the old neighborhoods altogether, moving to other parts of the city and suburbs for the first time. Toward the end of the war another significant change in the Latino population was noted. For the first time, under a contract labor agreement similar to that which had brought the Braceros, Puerto Rican workers came to the city to work in light industries, mostly on the north side of the city. By 1950 the "Spanish-speaking" population had reached 35,000 and was growing once again. Recognizing the increasing visibility of Latinos, the Metropolitan Welfare council formed the Spanish-Speaking Commission, which was immediately charged with preparing a status report on this largely new population.

Vietnam War Memorial, Our Lady of Guadalupe Church Courtesy: Southeast Historical Society New migrants from Mexico, the Southwest, and Puerto Rico, and Cubans late in the decade, arrived in the city in the 1950s. The Wildcats and others began to tentatively assert leadership in the rapidly growing community. They started families and businesses, they became politically active, especially in Cook County Democratic politics, and they formed new community organizations like the Mexican Civic Committee and the Pan American Committee to address issues of common concern. Like Latinos elsewhere at the time, they favored non-confrontive strategies. One issue they seem not to have addressed is the round-up of undocumented workers, many of whom had arrived during World War II. "Operation Wetback," returned millions of Mexican immigrants from across the United States and several thousand from Chicago. Also without fanfare, several local Latinos who had been vocal during the union organizing of the 1930s were charged with communism and targeted for deportation in the 1950s under the terms of the McCarran Walters Act. With the aid of her employer, Lupe Perez Marshall Gallardo fled to Jamaica, never to return, but Refugio Martinez, even though debilitated with a chronic heart condition, was deported to Mexico after he had exhausted all judicial appeals. The early 1960s saw the end of Bracero contract legislation and the overhaul of immigration policy in 1965. By this time in Chicago striking changes occurred in the old south-side Latino neighborhoods and dramatic new developments elsewhere in the city. In the Hull House area, Mayor Richard J. Daley had realized his dream of locating a new campus of the University of Illinois in the city, precisely where the early Near West Side Mexican settlement had been formed. After a gallant battle, residents scattered to the suburbs or to a neighborhood called 64 Pilsen a few blocks to the south. In the meantime, both the packinghouse industry and the steel mills were beginning to suffer decline. The surrounding neighborhoods, Back of the Yards, and South Chicago felt the after effects of cutback and unemployment. On the north side, several neighborhoods that had welcomed Puerto Ricans were also "benefiting" from urban renewal in the 1960s. Lincoln Park and Lake View had started to gentrify and were too expensive for Latinos. Most moved to West Humboldt Park or West Town. The turbulent 1960s did not bypass the Latinos settlements. In response to their displacement as well as to the Vietnam war and civil strife, there were several major disturbances, especially on the North side as the Young Lords, a former Puerto Rican street gang, asserted the rights of Latinos in a series of demonstrations. On the southside, throughout the neighborhoods new organizations sprang up to address local needs, especially over-crowded schools. The gentility of the 1950s was forgotten. This increasingly noisy population was also growing: by 1970 the census counted more than 250,000 Latinos in Chicago and showed that it was the most ethnically diverse Latino population in the United States. Since 1970 Latinos, especially Mexicans, have continued their migration to the city and the metropolitan region of Chicago. By 1990 there were almost 600,000 Latinos in the city and close to one million living in the region. Irene Hernandez was the first Latino elected to office in 1974 when she became a member of the Cook County Board representing the county's seven million residents. Since then a series of Latinos has been elected as city aldermen, state representatives and senators,and suburban mayors and councilmen. In 1992, the first Illinois Latino congressman was sent to Washington. Latinos have been active and instrumental in local school reform efforts and economic development since the early 1980s. Many were surprised to learn that after Michigan Avenue's swanky "Magnificent Mile," Pilsen's 26th Street is the city's most vibrant business district in Chicago. Currently, both the city police chief and the fire chief are Latinos. Frank Duran remembers the early days at St. Francis. Now retired, he and his wife Jovita are still active in the Pilsen community as volunteers in the now mostly immigrant neighborhood. They meet regularly with "old" Wildcats, not only to reminisce, but to discuss strategies for the next Latino election campaign, the next fund drive, the next Latino scholarship winner, the next problem to be solved. Despite profound and rapid changes in the last 75 years, the well-known Wildcats have signified and helped maintain continuity and stability in Chicago's Latino communities.

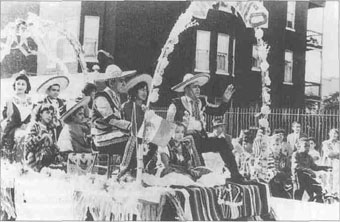

Mexican Independence Day Parade, September 15, 1957. Pictured is the Group Del Coro from Our Lady of Guadalupe Church. (Cordero Collection). Courtesy: Southeast Historical Society Click Here for Curriculum Materials

65

|

|

|