Guest essay

Ann Fisher is executive director of the AIDS Legal Council of Chicago. Barbara Otto is executive director of the SSI Coalition for a Responsible Safety Net.

A NEED AND AN OPPORTUNITY

It is time for Illinois to make Medicaid

available to all low-income seniors and disabled people.

The recent tobacco settlement could help

by Ann Fisher and Barbara Otto

Imagine trying to live on $3,800 a year without significant assets. Then imagine you are elderly or disabled and suffering from chronic health problems.

When you cannot pay your medical expenses, a social worker might encourage you to apply for Medicaid, the federal and state health insurance program administered by the Illinois Department of Public Aid. Medicaid, after all, is supposed to provide a medical safety net for our poorest citizens. By any definition, you are very poor — your income is less than half the federal poverty level of $8,050 per year — and your need for medical care is beyond dispute.

But, amazingly, you will be told that in Illinois you have too high an income to qualify. Based on an outdated formula created decades ago, the state of Illinois has determined that seniors and people with disabilities who have incomes greater than $308 per month — or more than $3,696 per year — have enough money to meet their own medical expenses. If these individuals become so ill that they need nursing home care, they will qualify for Medicaid. But unless their income is less than $308 per month, they will not receive Medicaid if they are trying to maintain their independence in the community. In other words, if they have more than $308 per month, they will be expected to meet their own health care expenses with their "excess" income.

Because of these harsh income criteria, the Illinois Medicaid program fails our most medically vulnerable citizens: seniors and people with disabilities who are living in poverty.

Our organizations routinely hear from people like this composite example. Let's call her Susan J., and say she's an 84- year-old widow with diabetes, hypertension and severe arthritis. Her Social Security check, based on her husband's work history, is $600 per month. Although she is living in poverty, her income is too high — by almost $300 — for her to qualify for Medicaid benefits. So each month, Susan J. must choose between buying the medications her doctor has prescribed — medications that can preserve her health and independence — and paying for food, groceries and utilities.

It is time for Illinois to join the 14 other states, including Missouri, Kentucky and California, that make Medicaid available to all low-income seniors and disabled citizens.

People who would be helped by this change are typically like Susan J. Census data indicate that more than two-thirds are women, and approximately 46 percent live outside of the Chicago metropolitan area. Another 17 percent live in the Chicago suburbs and the remaining 37 percent live in the city of Chicago.

How many Illinoisans would be affected by the change we are advocating? Estimates range from 70,000 to 150,000. We are working with state policy analysts to refine this figure. Importantly, many of these people are in a special "spend-down" program enabling them to get a monthly Medicaid card, and much of their service cost is already born by state government.

For these people, Medicare, part of the federal Social Security program, is not enough. Susan J., like most seniors and disabled people in Illinois, has Medicare insurance. After she pays certain deductibles and co-payments, Medicare will cover most of her hospital bills and many of her doctor bills.

But Medicare provides no coverage for other essential health care costs, most conspicuously prescription drugs. (Prescription medicines can easily be the most expensive part of a person's routine medical expenses.) So Medicare alone cannot provide Susan J. with the health care she desperately needs.

There also are private "Medigap" insurance policies marketed to seniors to supplement Medicare coverage. Some of these policies offer some prescription drug benefits. But the costs of these policies are far beyond the financial reach of people living in poverty. And there are Medicare HMOs, available in some counties in Illinois, which provide certain supplemental services without additional cost. But even in the increasingly limited areas of the state where they are an option, these services fail to provide full coverage for prescription drugs.

The "spend-down" program is not the answer either. When people with high medical bills like Susan J. apply for Medicaid, they may be told that they qualify for "spend-down." The system is so complex that most people do not even try to understand it. But even a brief discussion of the system at its best illustrates its serious inadequacies.

In theory, it works like this: Susan J., whose monthly income is $292 more

24 February 1999 Illinois Issues

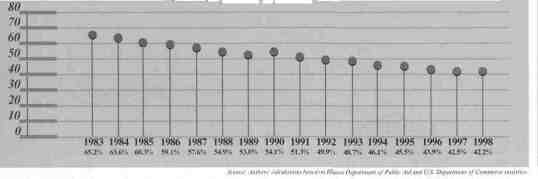

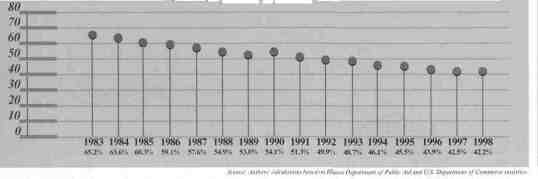

Income level at which elderly and disabled lose access to regular Medicaid, shown as percent of poverty level

than the Medicaid eligibility limit of $308, is told that she can get a Medicaid card for every month in which she spends $292 out of her own pocket on health costs. The underlying idea is that she only needs $308 for her living expenses and can spend all of her "excess" income above that amount on her medical care. Only when she has done that will she be eligible for a Medicaid card.

To get that card, Susan J. must bring to her local Department of Human Services' office bills or receipts for medical services not covered by Medicare, and dated within the last six months, totaling more than $292. In return, she will get a Medicaid card for one month only. She cannot use that Medicaid card to pay those prior bills or to get reimbursed for money she has already spent. To get a Medicaid card for a second month, Susan J. must bring in another batch of bills or receipts totaling another $292. She must do this each and every month that she wants a Medicaid card.

This system, cumbersome and harsh in theory, is even worse as implemented in overworked and understaffed Department of Human Services' offices. The predictable result is that very few people are ever able to use it as a reliable source of Medicaid coverage. But today, we see it as the best that's available in Illinois for Susan J.

Medicaid for low-income seniors and people with disabilities has not kept pace with improvements for other groups. It is now available only to individuals who have income at or below approximately 47 percent of the federal poverty level. This figure represents a substantial decline in Medicaid eligibility for this population over time.

Illinois seniors and people with disabilities have been left behind as Medicaid coverage has expanded in recent years for other groups. Illinois has recently expanded Medicaid eligibility for children (who now may have incomes up to 185 percent of the federal poverty level), pregnant women (up to 200 percent of poverty level) and parents transitioning off the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families program (up to 100 percent of poverty level). A sense of fairness and equity calls for the elderly and disabled to have their health care concurrently improved.

Further, seniors and people with disabilities who have not had significant connection to the workforce often receive federal Supplemental Security Income benefits. This year, the SSI amount is $500 per month.

If a person receiving a $500 SSI check applies for Medicaid, she will be approved, even though her income is more than the normal $308 cutoff amount. This is because federal law states that SSI income must not be counted when a state is deciding whether someone is eligible for Medicaid.

But if someone is getting any income other than SSI benefits, such as regular Social Security retirement or disability benefits, that income is counted for Medicaid purposes. A person with a $500 Social Security retirement check, for example, will be considered to have $192 "excess" income each month ($500 minus $308). That person will be denied Medicaid or placed on spend-down.

Both should have access to Illinois' Medicaid program.

A golden opportunity exists for Illinois to do the right thing and correct inequities in its Medicaid system and improve health care for the elderly and disabled: Illinois Attorney General Jim Ryan has joined colleagues from 46 other states in signing the historic settlement recently negotiated with the major tobacco companies.

Illinois will receive a total of $9.1 billion under the tobacco settlement between the years 1998 and 2025 — an average of more than $360 million per year. The settlement is designed to address Medicaid costs incurred by states as a result of smoking-related illness. States have wide latitude in deciding how to use their settlement money, but most are appropriately using it to strengthen their Medicaid programs.

With or without the tobacco settlement, the time has come to correct the inequities in Illinois' Medicaid system by joining the other 14 states providing Medicaid coverage to all seniors and people with disabilities who live in poverty. But with the tobacco settlement, this must become a top priority for state policy-makers. Rarely does a better chance come along to improve health care for the needy — and pay for it, too.

Illinois Issues February 1999 25