It was a rude thing for an invited guest to do, but the architect and his wife weren't invited. A self-guided (and unauthorized) tour led them to the Baehrend's upstairs patio.

"I say, 'Excuse me, but are you staying for dinner?'" Diana Baehrend remembers. "I see the husband and he's literally pasted to the side of the home. He tells me he's from Morocco and he's an architect whose specialty is brickwork and masonry. How can we chase someone like that out of our yard?"

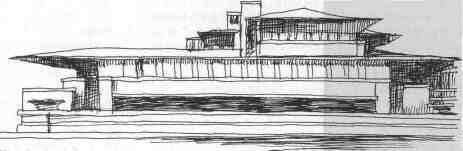

The average homeowner would find a way. But then again, the Baehrends don't live in an average home. Built in 1902, the couple's low, wide home hugs the ground like a panther. Underneath its wide, hip roof sits a sparkling line of leaded glass windows designed to catch the setting sun. It's a masterpiece of residential architecture, covered in textured brick and designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. The Baehrends bought the house in 1997.

Given the home's pedigree, it's no wonder the Moroccans chanced an unauthorized visit to the Baehrend's patio. Though the house sits on a street with six other Wright creations including Wright's home and studio, which is open for tours — the Baehrends have endured a conga line of interlopers, sneaks and window-peekers, all trying to steal an up-close look at a Wright home.

"There is definitely a mania there," Diana Baehrend says. "I can see from one summer to the next that more people are looking at [the home]. Wright is everywhere."

Wright died April 9, 1959. The four decades that passed are time enough to dull the shine and fleck the gold leaf off most historical icons, but not Wright. There is an insatiable interest in the architect. Tourists flood the streets of Oak Park to see Wright's hand in nearly two dozen homes. His Dana-Thomas House in Springfield is among the state's top tourist attractions. Modern-day builders vainly attempt to copy his architectural style.

Bookstore shelves are swollen with nearly 400 Wright biographies and dissections of his work and genius. Among the latest is Frank Lloyd Wright's Living Space by Gail Satler, which looks at Wright's novel use of space to create rooms that flow together.

It is almost as if Wright never died. But why is Wright's fame on the increase? Last year's expansive Ken Burns documentary on PBS certainly helped, but the answer is larger than that.

Wright --- arrogant, abrasive, talented, stubborn and vain --- fits an American ideal of the trailblazer: the lone genius who single-handedly paved the way for others. He's Frank Sinatra with a drafting pencil: Wright did it his way.

It's a quality that is all the more endearing in light of what passes for high-end residential construction these days. The classes of people who hired Wright — or other quality architects of the time, including Walter Burley Griffin, Talmadge & Watson and George W. Maher — now seem satisfied with building graceless, steroidal three- story homes with cathedral ceilings and skylight-perforated roofs.

Compare Wright's Robie House in Chicago or the Ward Willits House in Highland Park with the latest direct- from-the-contractors'-catalog McMansion and Wright's genius is all the more apparent ---- and missed.

"Wright's houses are fresh and vital and designed to really trigger human emotion," says Timothy Samuelson, curator of architecture for the Chicago

32 / October 1999 Illinois Issues

Historical Society. "And human emotions haven't changed that much. They're the same in 2000 as they were in 1900."

What did Wright do that was so important?

Early in his career, he helped perfect an American architecture. His Prairie School homes did not look to the Old World as a model and helped shatter the prevailing notion that fine architecture must bow to Victorian, Greek and Roman revivalist styles. It was a gospel that Wright's mentor, Louis Sullivan first preached. Sullivan excoriated the European revivalist City Beautiful movement that came out of the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago. When Sullivan said Americans needed an American architecture, Wright was among those who heeded the call.

Ironically, Wright helped break Europe of its ties to Old World architecture. When Berlin publisher Ernst Wasmuth published a portfolio of Wright's work in 1910 and 1911, young European architects such as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier began to rethink their own work. European modernism, which influenced postwar American architecture, actually owes a debt to Wright.

Wright did not invent the Prairie School — indeed, he wasn't that fond of the title — but his work represents the best examples of it. Wright's homes were ones in which great spaces opened up to other great spaces without being separated by hallways and doors. He even designed houses to take advantage of nature and the movements of the sun, not just skate the perimeters of zoning ordinances.

To Wright, a building's form was an outgrowth of its function, not of ornament and design appendages. It was another lesson that Sullivan taught Wright. And to make the building function, Wright would also design furniture, urns, curtains and fixtures. For the Avery Coonley Estate in suburban Riverside, Wright even designed dresses for Coonley's wife to wear in the house.

"That is part of the story that often gets lost," says Samuelson, a Sullivan expert. "The whole process out of which Sullivan created buildings and out of which Wright created buildings — is that if you have a knowledge of the practice of architecture, knowledge of the site and of the technology available to you, a knowledge of the functions that are supposed to take place in a building, you would then be able to synthesize this completely in your mind and create a building. Even before you set pen to paper. And both men were able to do this."

Wright also developed greater, though lesser heralded projects. He designed houses with carports as early as 1909, foreseeing the future impact of the automobile. Just before World War I, he joined a builder to create a brief, early stab at high-quality prefabricated housing. The American System-Built homes were not in the same league as the domiciles he constructed for rich clients, but they were neat two- story gems with clever design, art glass, brick fireplaces and nice woodwork. His Usonian homes, first built in 1939, were efficient, attractive housing. With low, flat roofs, open kitchens

|

For more information

Frank Lloyd Wright's Living Space

Frank Lloyd Wright and By Paul Samuel Kruty University of Illinois Press, 1998 Focuses on a singular work of Wright's, the demolished Midway Gardens, as a pivotal point in the architect's career. Constructed in 1914 as an open-air concert garden on the southern edge of downtown Chicago. Midway Gardens marked a change in Wright's approach to his craft. Kruty contends Wright's design unified art with architecture by devising a more ornamental style that characterized his work for the next 15 years. This analysis examines the concepts behind Midway Gardens, as well as the pervasiveness of its influence on architecture.

50 Favorite Rooms by

Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography |

Illinois Issues October 1999 / 33

and centrally located fireplaces, the Usonian was the postwar American suburban house — 20 years ahead of its time. "As time would change, technology would change and he would evolve personally," Samuelson says of Wright. "Every building that's created is as fresh as the new sunrise. He very seldom would fall into formula."

But Wright was far more than a residential architect. He designed futuristic office complexes, such as the still stunning Johnson Wax Building in Racine, Wise.

"Every time I see that building, I'm blown away by it," says author John Zukowsky, architecture curator for the Art Institute of Chicago.

Wright took the old beer-hall concept and created the late, great Midway Gardens entertainment spot just west of the University of Chicago. The short-lived Shangri-la is remembered and vividly shown in Frank Lloyd Wright and Midway Gardens, by University of Illinois architecture professor Paul Samuel Kruty.

Wright's Unity Temple in Oak Park is heralded across the globe because it is shorn of all the "religious" design trappings that are usually found in worship spaces. Instead, it applies perspective and shadow to create a reverent, sanctified place.

In a career that stretched from the gaslight era to the Nuclear Age, Wright constantly reinvented himself. He was more than just the Prairie School architect or the man who created the famous Fallingwater home in Bear Run, Pa., or the Guggenheim Museum in New York. All those things and more, Wright lived a tempestuous life marked by scandal, triumph, bankruptcy and victory. There was so much tumult, in fact, the FBI kept a voluminous file on Wright throughout most of his life.

This mixture of history, beauty and genius adds to the appeal of the Arthur Heurtley home, owned by the Baehrends.

"Were we Wrightophiles — absolutely crazed? No," Diana Baehrend says. "But we like Prairie [School], clean style, minimalist. That's the style we were comfortable with. We've always appreciated Wright."

The husband-and-wife investment bankers left few areas of the home untouched in a massive restoration effort that included demolishing non- original walls and recreating Wright's color scheme. The Baehrends are looking to track down the home's original furniture.

Is it worth the trouble?

"You are in such a fine piece of architecture and anywhere you sit in the house is enlightening," Diana Baehrend says. "We get excited about going home," Ed Baehrend adds.

Zukowsky says Wright's fame is not likely to wane. "People will talk of Wright years from now, just as they discuss Leonardo da Vinci and the Mona Lisa," he says. "There will always be discussions and reinterpretation of his work, because that's what happens with great work."

Lee Bey, architecture critic for the

Chicago Sun-Times, has written

extensively about Wright.

34 / October 1999 Illinois Issues