Student Perceptions of

Leisure Service Careers

Research reveals that most students today chose careers in commercial

recreation, and a job in the public sector may be a "default" option

BY DANIEL G. VODER, JOHN WEBER AND

CYNTHIA J. WACHTER

|

(This research)

suggests a

growing disparity

between the

demand for and

supply of

competent and

enthusiastic public

leisure service

personnel in the

state of Illinois.

|

For many of us who prepared for careers in recreation

and parks by attending colleges and universities in the

1960s, 1970s and 1980s, the only "real" option was

working in the public sector at either the local, state or

federal level. Our professors and mentors did recognize

the "other" areas, but usually only in passing. Some students eventually found careers in the nonprofit and commercial venues, but in many cases it was by default. They

were unsuccessful in finding positions in park districts

or municipal settings or the state or federal government

and they settled for something else.

Today that is no longer the case. Careers in leisure

services in the public sector are no longer "the only game

in town." Students can now opt for careers in the commercial and nonprofit arenas as well as in the burgeoning corrections industry, military recreation and the corporate realm.

Instead of 80 percent of park and recreation students

entering the public sector and the other 20 percent

spreading themselves across the various other fields, the

opposite appears to be true in the '90s. This trend could

result in serious consequences for the future provision

of public leisure services at the local level in the state of

Illinois.

Research Goals and Method

This exploratory research project examined the attitudes of leisure service majors in Illinois universities toward careers in recreation and parks in the public, commercial and nonprofit sectors. Specifically, the objectives

of the study were to determine the percentage of students who aspire to careers in each of the sectors and

what perceptions they hold of careers in the various sectors.

Self-administered questionnaires gathered demographic and attitudinal information from recreation and

park majors at Western Illinois University, Illinois State

University and Eastern Illinois University in the fall of

1997. The majority of the questions on the survey were

closed-ended. For example, the survey included the question, What is your opinion of entry level wages in the

public leisure service sector? Response options included

very high, high, average, low or very low. In addition,

the researchers sought more detailed information by including an open-ended question to determine students'

primary reasons for aspiring to careers in a particular

area.

Following brief instructions, including a statement that

completion of the questionnaire was voluntary and responses were anonymous, professors handed out a total

of 404 survey instruments during class. Although a few

of me questionnaires were only partially completed, all

were returned promptly. The high response rate (which

approached 100 percent) and the researchers' belief that

the students from the three aforementioned institutions

were representative of students in leisure service programs in other Illinois universities and colleges, allowed

the researchers to make inferences and conclusions with

some degree of confidence. Moreover, the responses by

students did not differ significantly between institutions.

This does not mean that other institutes of higher education in Illinois might not produce different results with

the same survey.

The problems of dividing the leisure services field into

three separate sectors are fully appreciated. The growth

of shared revenue sources, the adoption of business principles and marketing strategies and cooperative endeavors has contributed to a blurring and subsequent confu-

January/February 1999 /17

sion of the private, public and nonprofit

worlds. Moreover, some students aspire for

careers in areas in which opportunities exist

in multiple sectors. For example, outdoor recreation positions can be found in private,

nonprofit and public agencies. To address the

issue, the survey included a short explanation and diagram to explain this common

classification system and its use in the questionnaire.

Findings

Valuable insight can be gained by considering the overall profile of the students involved in the study. Respondents were evenly

split between males (49%) and females

(51%). Ninety-four percent (94%) were undergraduate students and 80% of all respondents were recreation or leisure service majors. The majority (75%) had taken their first

recreation class since 1996 with 48% having taken their first class in 1997. Many students indicated they had previously worked

in the leisure service field: 41% in the public sector, 37% in the commercial sector and

34% in the nonprofit sector.

|

Chart A

STUDENTS'CAREER ASPIRATIONS BY SECTOR

|

Career Aspirations

One of the most informative questions

posed to students focused on their career

aspirations. In response to the statement,

"Indicate the sector in which you would most

like to work," 50% percent indicated they

would most like to work in the commercial

sector, 35% preferred to work in the public

sector and 15% hoped to work in the nonprofit sector (see chart A).

|

|

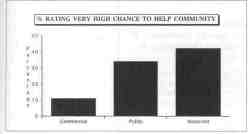

Chart B

CAREER STATUS RATING OF HIGH OR VERY HIGH

|

Career Status

Respondents held different perceptions of

the status of careers in the different areas.

Employment in the commercial sector held

the highest perceived status with 61% of the

respondents indicating either very high or

high status. Fifty percent (50%) of the students perceived that a public sector career

rated either very high or high status. Only

38% indicated that a career in the nonprofit

sector warranted very high or high status (see

chart B).

|

Use of Technology

Students believe that technology is used

much more in the commercial sector, less in

the public sector and the least in the nonprofit sector. Eighty percent (80%) of the

students rated the use of

technology in the commercial sector as being "very

much" or "much" in comparison to 56% of similar responses in the public realm

and only 30% in the nonprofits.

Wage and Compensation

|

|

Because wages and other

compensation are of particular importance to those contemplating a particular career

field, the survey posed several related questions in this

area. Students' perceptions of

entry-level wages were realistic. Nineteen percent

(19%) thought that entrylevel wages in the commercial sector were either high

or very high, 10% thought

that entry-level wages were

high or very high in the public sector and 4% of the respondents perceived entry-level wages to be

high or very high in the nonprofit realm.

Only nonprofit agencies' entry level wages

were rated low by more than half of the students.

|

When this information is combined with

data regarding perceptions of top management salaries, significantly different perceptions of the three sectors become evident.

Seventy-six percent (76%) of the respondents

thought that top management salaries in the

commercial arena were either high or very

high; 56% thought that the salaries paid to

top management in the public sector were

high or very high and only 36% believed

that top managers in the nonprofit sector

made high or very high salaries.

Not surprisingly, students' perceptions of

the benefit plans for each sector are consistent with their perceptions of salaries. Commercial sector benefits plans are rated highest, the benefit plans of the public sector are

in the middle and the benefit plans in the

nonprofit sector are perceived to be the lowest (see chart C).

Getting a Good Job

Interestingly, students are equally optimistic about "getting a good job" in each area.

The chances of getting a good job in the

commercial sector are rated very good or good

according to 68% of the students, 67% believe that to be the case in the public sector

and 65% in the nonprofit sector.

The optimism shown by students in regard to getting a good job appears to carry

over into the perception of their chances of

advancement in each sector. The commercial sector once again leads the way with 75%

of the students rating the chances of advancement as very good or good followed by 66%

in the public sector and 60% in the nonprofit sector.

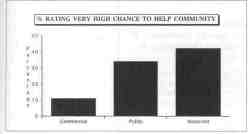

Helping the Community

|

|

The question regarding the students' perception of the "chances of helping your community" shows the greatest difference with

the nonprofit sector rated highest (42% believe they have a very good chance of doing

so), the public sector rated in the middle with

33% perceiving a very good opportunity and

the commercial sector last with only 11%

indicating a very good chance of helping their

community (see chart D).

|

Conclusions and Discussion

What do college students think of careers

in leisure service in the public, commercial

and nonprofit sectors?

18/ Illinois Parks and Recreation

The commercial sector appears to be a very

attractive career choice for students. Of the

three areas, it is rated number one in terms

of status, the amount of technology employed, entry level salaries, top management

salaries, benefits packages, opportunities for

advancement and the chances of getting a

good job out of college.

At the other end of the spectrum, the nonprofit sector has the lowest career status, uses

little technology, and has the lowest compensation plans including entry level wages,

top management level salaries and employee

benefits. On only one quality did nonprofits

rate the highest: that of the possibility of

helping the community.

In every case, careers in the public sector

fell between the extremes. It was lower in

status than working in the commercial sector but above the status of working in the

nonprofit sector. The amount of technology

used to accomplish the job in the public

realm was in the middle. Students indicated

that they thought the wages, salaries, benefits and chances of advancement were better than those in nonprofit agencies but not

as good as those found in the commercial

sector. The chance of doing good for the

community was not as good as that in the

nonprofit area but much better that the opportunity of doing good

things for the community in

the commercial sector.

Given these perceptions

(and it is important to remember that these are perceptions only and may or may

not reflect reality) it should

be no surprise that 50% of

the students aspire to leisure

careers in the commercial

field. The narrative answers

to the open-ended questions

regarding this interest supports the quantitative data.

The following candid

narrative response captures

the sentiment of many students: "It (the commercial sector) is the best opportunity to

make the most money."

Others mentioned that

they liked the idea of "being

entrepreneurial and someday

owning my own company. "

The narrative responses

for having an interest in a career in the nonprofit sector were also consistent with the

short answers. An altruistic theme was clearly

evident. Several made note that they expected

to earn considerably less money in this area;

however, they were willing to make the sacrifice. According to one: "I have volunteered

in the nonprofit field and now it is my major

Interest. I feel it is a way to make a difference."

The reasons expressed for going into the

public sector were much more varied. Some

students commented on their perception that

the pubic sector offered the best opportunities for "making quality programs that can be

offered to almost anyone." Others noted that

careers in outdoor recreation or therapeutic

recreation would most likely occur in the

public sector. The chance to interact with a

diverse collection of professionals and clients

was attractive to some students.

For the most part, previous work experiences in the public sector (usually in the summer months) seemed to have been positive

and created an interest in the field. After indicating a strong aspiration for a leisure service career in the public sector one student

wrote: "I have worked there for three years, I

know how things are run. I like the public sector. "

One narrative response provides an interesting insight not only because of what was

written but because of what was not written. An undergraduate student noted: "I am

split between the nonprofit and the commercial sector. I would like to benefit my community but making a living and good money is

why I'm going to college. "

In recognizing the salient qualities of the

commercial and nonprofit areas, the student

seems to have overlooked the public sector.

The data, when considered as a whole, suggests that some of the erosion of interest in

public sector leisure service careers might be

related to this phenomenon of gravitation

to the extremes. If students desire to make a

lot of money and live very comfortable lives

they tend to the commercial side: if they

desire to contribute to helping individuals

or society they tend to the nonprofits. The

middle ground (in which Illinois park and

conservation districts and municipal departments reside) may now have become the

"default sector."

Indeed, there appears to be a larger number of students who enter the commercial or

nonprofit sectors only to find that "it is not

what it is cracked up to be." Some of them

turn to the public leisure service area, and

some of them leave the field altogether.

Obviously Illinois park and conservation

districts, forest preserves and municipal park

and recreation departments need bright

young people to replace professionals who

leave for a number of reasons. More than

30,000 people are employed by approximately 400 public park, recreation and conservation agencies in Illinois. A conservative

3 percent attrition rate would require 900

new professionals with the philosophy,

knowledge and skills unique to the leisure

services field each year. (This turnover does

not take into the account the impact of a

significantly large cadre of mature professionals who will likely be retiring in the next five

to ten years.)

Each year Illinois' universities and colleges

produce between 300 and 400 students with

recreation and park degrees. According to this

study 35 percent of those students (between

100 and 140) aspire to careers in the public

sector. Unfortunately, some of those who

desire such careers will either leave the state

or be unable to accept positions for other

reasons. And inevitably, a few will lack the

skills and knowledge necessary for the positions available.

January/February 1999 /19

These numbers suggest a growing disparity between the demand for and supply of

competent and enthusiastic public leisure

service personnel in the state of Illinois.

While some of this can and should be filled

by professionals from other fields, a personnel crisis may loom in the future.

It is important to remember that we have

discussed the perceptions students hold of

careers in the field; and some of those perceptions might not be based in reality. For

example, the entry level wages and the salaries of top managers in Illinois park districts

are at least comparable to those in the commercial sector. In many cases, the employees' fringe benefits and job security are better in the public sector. And students do have

the opportunity to genuinely contribute to

the lives of individuals and to the quality of

their communities.

Armed with the most current and enlightening data, it will still take a concerted effort

to change the misconceptions that some

young people have about careers in the provision of public leisure services. We should

not attempt to direct every student to a career in the public sector: many simply are

not appropriate for a career in this sector and

would do much better in the commercial or

nonprofit sectors. However, university faculty and administrators and public leisure

service professionals must actively laud the

benefits of and advocate for careers in Illinois park and conservation districts and

municipal park and recreation departments

if we are to avert a personnel crisis in the

next decade. •

January/February 1999 /20