|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

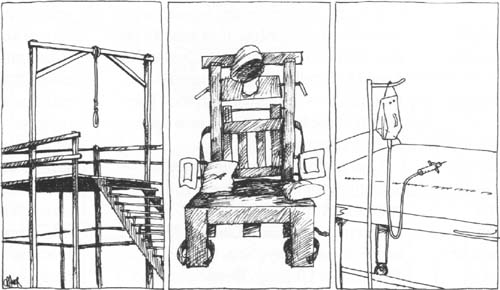

Guest essay TOUGH ASSIGNMENT This may be the optimum moment to reconsider Illinois’ death penalty by Frank Kopecky Illustration by Mike Cramer

The panels investigating problems associated with Illinois’ death penalty already face a tough assignment. Still, I want to suggest three more challenges. First, the members of the various commissions named by the governor, the state Supreme Court, the state attorney general and two of the state’s legislative leaders might want to address a fundamental question: whether keeping this state’s quarter-century-old capital punishment statute is even worth the trouble. Second, they ought to spend at least some time weighing the probable consequences of whatever reforms they recommend. Third, if they believe reforms will keep innocent people from being convicted of capital crimes, they should consider extending their recommendations to the adjudication of all crimes. In fact, this may be the optimum moment to tackle these issues. Last January, Illinois became the first state to put a moratorium on executions since the U.S. Supreme Court allowed the states to reimpose capital punishment. Gov. George Ryan, calling Illinois’ record of putting innocent people on Death Row “shameful,” says he’ll halt all executions until he can figure out why the system has gone awry and how it can be fixed. He made that announcement after the 13th Illinois Death Row inmate was released. Ryan subsequently appointed a 14-member commission to review procedures used to impose the state’s ultimate sanction. That commission, headed by former U.S. Sen. Paul Simon and retired federal Judge Frank McGarr, joined reviews already underway at the behest of the state’s top court, Illinois Attorney General Jim Ryan and the General Assembly. The governor’s action, taken under his constitutional power to review sentences, attracted international attention, in part because Ryan supports capital punishment. But pressure for such a moratorium has been mounting for more than a year, as even the most ardent death penalty proponents began to sense that something was wrong. Although none of the study groups has been asked to consider abolishing the death penalty, that issue underlies the current discussion. Because capital punishment is an irrevocable penalty, there is a greater need for certainty. And fairness. That is difficult under the best of circumstances. The late U.S. Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun ultimately concluded it was impossible. “It seems that the decision whether a human being should live or die is so inherently subjective, rife with all of life’s understandings, experiences, prejudices and passions, that it inevitably defies the rationality and consistency required by the Constitution,” he said in 1994, following his remarkable change of heart on capital punishment. “I feel morally and intellectually obligated simply to concede that the death penalty experiment has failed.” Blackmun was on the bench in 1972 when the high court swept away death penalty laws throughout the nation, including Illinois’ law, ruling that capital punishment had been applied capriciously and challenging the states to wrestle with whether it is “cruel and unusual.” The justices then decided in a series of cases that capital punishment can be used if it specifies which types of murder are covered and narrowly defines the standards by which the law can be applied. Illinois Illinois Issues May 2000 | 32 rewrote its statute in 1973, but that version was overturned by the state Supreme Court. The current law was approved in 1976. The review panels have been charged with suggesting means to assure that the death penalty is imposed in a fair manner. Yet now may be the time, as Blackmun concluded, to stop tinkering with the machinery. Still, the death penalty is popular with the public. A February Gallup Poll shows that 66 percent of Americans favor it, while only 28 percent oppose it. The lowest level of support for the death penalty was in the mid-1960s, when only 42 percent of those polled favored it. Since then, support for the ultimate sanction has followed growing concern about crime and public safety, reaching a peak in 1994 with 80 percent supporting the death penalty. And Illinois voters in a special referendum associated with the enactment of the 1970 state Constitution rejected a proposal to abolish the death penalty by about a 2-to-1 margin. These results would seem to settle the matter. However, when given the option of choosing life imprisonment without parole, those choosing the death penalty dropped to 52 percent in the most recent national Gallup Poll. And in a poll of Illinois voters conducted last February for the Chicago Tribune, 54 percent of voters said they supported the governor’s moratorium, while 37 percent opposed it. Nevertheless, in that same poll, 63 percent of voters said they favor the death penalty. Thus, while public opinion may be changing, it’s not clear by how much. And Illinois policy-makers are likely to opt to continue tinkering with the system into the near future. So what has been our national experience with the “death penalty experiment,” as Blackmun termed it? Since 1976, 38 states have approved death penalty statutes, though to date most executions have been conducted in the southern states. At 12 executions, Illinois is in second place out-side the South, behind only Arizona, which has carried out 21 executions. Overall, a disproportionate number of minorities are being executed. And those executed are almost exclusively male. According to federal Bureau of Justice statistics, through the end of 1998, 98.6 percent of the individuals executed in the United States were male; 43 percent were black; 12 percent Hispanic. In Illinois, there were 162 individuals on Death Row at the end of March, 105 of them black, 49 white and eight Hispanic. All but three of them were men. This data may underline Blackmun’s concerns about the inherent subjectivity of the death penalty. But of more immediate concern to Illinois policy-makers is the high number of procedural errors found in capital cases. And this is likely to be the focus of recommendations by the members of the Governor’s Commission on Capital Punishment and the other groups charged with studying Illinois’ capital punishment system. Assuming no major revision in criminal procedure, they will likely focus on trial practice at the conviction and the sentencing stages. The recommendations will most likely fall into three major categories: improving the quality of legal representation; controlling the behavior of prosecutors and law enforcement; and tightening court procedures. One proposal for improving representation would seem to be a given: that lawyers who participate in death penalty cases for both the state and the defense, as well as the judges who conduct the trial, would have to have several years of experience in criminal law. Another might require a team of two experienced lawyers with a third less experienced lawyer-in-training to represent defendants. And all lawyers and judges could be offered specialized training in handling death penalty cases. A number of suggestions are likely to deal with pre-trial procedures. Law enforcement could be required to investigate leads that may prove innocence as well as guilt. Funding for investigators and paralegals could be increased. Scientific evidence, including increased use of DNA identification, could be considered fully. Confessions could be videotaped. Prosecutors could be required to share more information with the defense, including evidence that would tend to prove innocence. And they might be required to provide the defense with early notice that the death penalty is being sought. The third category of recommendations might pertain to court procedures. The panel members may want to give the trial judge a greater role in the development of a case and in monitoring discovery to assure that evidence is shared. They might want to restrict the admissibility of informant evidence, particularly when the evidence is obtained as a result of plea bargaining. They might like to see more control over the makeup of juries and limit juries’ discretion. Commission members might also want to increase funding for appellate lawyers and require those lawyers to be available to consult with trial lawyers. And they could increase the burden of proof from “beyond a reasonable doubt” to one in which there is no residual doubt. At least two potential suggestions from the panels would require action by the General Assembly. They might, for instance, propose that the legislature limit the number of offenses that are currently eligible for the death penalty. They could also create professional teams of experienced lawyers with the ability to prosecute or defend cases throughout the state. If all or many of these proposals were enacted, it is clear that they would make several important changes in the manner in which criminal law is practiced. First, such recommendations would create a pool of experienced lawyers and perhaps judges, investigators and law enforcement officers available to investigate death penalty cases and conduct trials. Second, to make this pool of death penalty specialists available throughout the state in a cost-efficient manner, these functions would need to be centralized in an existing or a newly created state agency. Third, the reforms would result in an increased openness and monitoring Illinois Issues May 2000 | 33 of the fact-gathering process at the trial preparation stage, either by more directly involving the judge or by requiring the sharing of information. Finally, reforms that improve the quality of the defense attorneys and those directed at increasing the burden of proof or limiting the introduction of evidence would make it more difficult for the state to convict and impose the death penalty. While these changes undoubtedly would improve the quality of trials and should consequently address the issue of convicting innocent persons, these changes would also have less immediately visible, but perhaps more important, consequences than the various death penalty commissions are charged with considering. For example, better fact-finding and improved hearings might give us the satisfaction of believing the offender is guilty of the offense charged, but it might not satisfy the concern that this particular individual deserves to be put to death. This latter point is inherently a value choice that is made by the jury weighing many subtle factors. Furthermore, there is evidence that the way the defense is structured may affect the jury’s viewpoint on whether capital punishment is appropriate. Juries are influenced heavily by whether the convicted criminal shows remorse for his acts. If a defendant vigorously denies that he committed the offense and the jury still finds guilt, that defendant is in a difficult position to demonstrate remorse. Ironically, in some instances those who claim innocence the most vigorously may be those who, when convicted, will be the most likely to be executed. In trials of cases we can never be certain; the best we can do is remove most doubt. To strive for perfect justice is to strive for the truly impossible goal. Beyond that, the reforms could end up increasing, not reducing, the time spent on Death Row, as well as increasing the number of individuals sent there. One goal is that lengthy appeals could be reduced if trials were conducted better. In theory, this is correct. But the pressure to assure that no innocent person is convicted and sentenced to death, and the desire to build in as many procedural safeguards as possible, will undoubtedly lead to appeals. The convicted individual certainly has an incentive to pursue every possible appeal, and the availability of qualified, highly motivated and publicly salaried lawyers may also encourage appeals. No trial is conducted without some error and, as every follower of Court TV knows, there are always opportunities to second-guess trial strategies. Unless there are rigid limitations on appeals, they are likely to continue. Of course these limitations will reduce the confidence people have that the death penalty was applied properly. In addition, these potential reforms are likely to be costly, from a financial and a social perspective. Developing a pool of experienced lawyers and other professionals to conduct death penalty cases will be expensive. State’s attorney and public defender offices across the state are staffed in large measure by young, less experienced attorneys. The salaries are comparatively low. To encourage attorneys to make a career in criminal law, the salaries will have to approximate the salaries of comparable attorneys in private practice. At present, most trial expenses are paid at the county level. County boards tend not to see criminal justice as a high budget priority, particularly the public defender’s office. For this reform to work, the state would have to budget and perhaps directly administer the funding, which means these recommendations will undoubtedly lead to more centralization. Centralizing the delivery of criminal justice services may be the right strategy, but it is not the way we do things now. It will reduce local control over decisions about charges and trial strategy. The various study commissions ought to consider this impact. The involvement of the judge in the evidence gathering stage and the requirement that evidence be shared will also change the adversarial nature of criminal justice in death penalty cases. In adversarial justice, both sides of the case prepare independently and present evidence before a neutral judge. The side that can best present the evidence and meet the burden of proof prevails. The common belief is that the truth will win out through this manner of presentation. However, there are many critics of the adversarial system, and perhaps it should be changed. The question of whether the basic approach used in criminal trials should be changed in death penalty cases must be addressed. Finally, many of the changes will make it more difficult to convict and to implement the death penalty. While in theory it is better for 10 guilty men to go free than one innocent man to be convicted, there is no certainty the public will accept that adage. While we are concerned now about convicting innocent people, how will the public react when someone who appears to have committed an offense is found not guilty because of a skillful, publicly funded lawyer? One of the purposes of the death penalty is to establish a sense of finality. A heinous crime has been committed and the victim, as well the community, has the need to restore the balance that existed before the crime by exacting a like punishment. One of the difficulties with the way the death penalty is being administered today is that the cases go on and on and there is no end. Many observers doubt the reforms being suggested will lead to more finality. Perhaps the only way to avoid this dilemma is to consider eliminating the use of the death penalty and instituting imprisonment without parole as the ultimate punishment. Maybe we should stop tinkering with the machinery of death and focus our attention on debating whether the death penalty should continue at all. Frank Kopecky is a professor of legal studies and public affairs with the Center for Legal Studies at the University of Illinois at Springfield. Illinois Issues May 2000 | 34 |

|

This page is created by Sam S. Manivong, Illinois Periodicals Online Coordinator |