|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

MEASURING UP Analysis by Jon Marshall Jason Braham earned steady A's and B's as a pupil at James Madison Elementary School in Chicago. He won an award for nearly perfect attendance. But when Jason took the Iowa Tests of Basic Skills last April, he choked under the pressure and his scores on the standardized exam slipped from the previous year. As a result, Jason had to attend summer school and wasn't allowed to participate in his eighth-grade graduation. "He's an honors student but doesn't take tests well," says Jason's mother, Tonja Braham. "Just because of one test, his graduation was stripped away from him." Jason and his peers better get used to taking more tests. Illinois schools are relying increasingly on standardized exams such as the Iowas to motivate and measure students, teachers and administrators. As the public clamors for better schools, standardized tests have become cornerstones of the academic calendar. School boards decree more of them. Newspapers print their results like basketball standings. Teachers adjust their curricula to boost scores. These tests are convenient and relatively inexpensive ways to grade students and schools. The danger, critics contend, is that we are putting testing ahead of teaching and relying too heavily on one form of measurement at the expense of others. In our zeal for assessment, we may be distorting what children learn and not preparing them fully for the challenges of this new century. If classroom time is devoted to drilling students on how to answer multiple-choice questions and write three-paragraph essays, the ability to memorize facts and quickly fill in answers is rewarded.

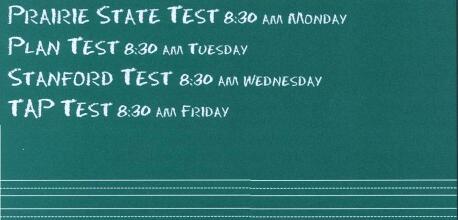

28 November 2000 Illinois Issues www.uis.edu/~ilissues Meanwhile, skills essential to navigating our increasingly complex world — thinking creatively, building teams, challenging assumptions, conducting research, sifting through conflicting data — are at risk of getting short shrift because they are harder to answer in the formats of standardized exams. "They [the tests] promote a rigid, formulaic, rote thinking style," argues Peter Sacks, the author of Standardized Minds: The High Price of America's Testing Culture and What We Can Do to Change It, published this year by Perseus Books. "The testing culture promotes thinking that is contrary to the innovative, critical, creative thinking we need to solve problems." Despite the concerns of critics such as Sacks, Illinois and other states are testing with greater frequency. Although schools have given standardized tests since the 1800s, their use surged in the mid-1980s when fears that foreign competitors would trample our economy led to calls for stricter academic standards. (It's interesting to note that the kids who grew up in the 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s, when our schools were less focused on assessment, ended up leading the technological revolution that has kept the United States the world's dominant economy.) American schools now give more than 100 million standardized tests a year, and every state except Iowa requires them, according to FairTest: The National Center For Fair & Open Testing, a Massachusetts-based group that advocates against the overuse of high-stakes tests. Educators use these tests to serve many goals: to set high standards for learning, to raise achievement levels, to give administrators and teachers feedback on the effectiveness of their instruction and to gauge the performance of schools and school districts. Sometimes their results are used to assign students to class levels, to decide whether or not they are retained or promoted to the next grade, or to even determine whether they graduate, according to "High Stakes: Testing for Tracking, Promotion and Graduation," a 1998 report by the National Research Council's Committee on Appropriate Test Use. "These policies enjoy widespread public support and are increasingly seen as a means of raising academic standards, holding educators and students accountable for meeting those standards, and boosting public confidence in schools," the report says. The Illinois General Assembly and the State Board of Education share this view. They are using testing as a crucial weapon in their campaign to raise statewide learning standards. The state's standardized tests "will help ensure all Illinois students get the same rigorous, high quality education through grade 12 they will need to be successful after high school graduation," State Superintendent of Education Glenn W. "Max" McGee said in June when introducing the new Prairie State Achievement Exam. Next April, Illinois high-school juniors will spend seven hours taking the maiden version of the Prairie State. The test comprises the ACT college entrance exam, two ACT Work Keys exams that measure job skills and a separate test based on statewide learning standards. Special education and limited English students can be exempted from the tests. Illinois public school students also must take the Illinois Standards Achievement Test, better known as the ISAT, for reading, writing and math in grades three, five and eight, and for science and social studies in grades four and seven. The ISAT and the Prairie State are far from the only tests Illinois students take. The state's 895 school districts are free to add their own layers of standardized exams, and add them they do. "The practice has been bigger and more extensive testing," says Thomas Kerins, assistant superintendent for school improvement standards and assessment at Springfield Unit District 186. The Chicago Public Schools, for instance, require students in grades three through eight to take the Iowa tests. Starting in 1996, third-, sixth-and eighth-graders like Jason Braham who didn't pass the Iowas have gone to summer school. If they failed the lowas again at the end of summer school, they repeated a grade. This summer, following criticism that it was relying exclusively on the lowas, the Chicago Board of Education added other measures such as grades and attendance for making retention decisions.

In high school, Chicago students also take the Tests of Achievement and Proficiency (TAP) in ninth grade, the Chicago Academic Standards Examination in ninth and 10 th grades, and the PLAN test, similar to the ACTs, in 10th grade. These tests create extremely high stakes for schools: Their scores determine whether the district's central office intervenes in their management, a process that can lead to the firing of principals and teachers. Other Illinois districts also employ an army of tests, although not always with the same high stakes as the Chicago schools. For example, Rockford Unit District 205 gives the Stanford tests for reading, math, vocabulary, spelling and listening in grades three through eight, or the Aprenda and Image tests to students with limited English proficiency. It also administers quarterly assessment tests created by its own teachers based on their own curriculum. While standardized tests remain popular among most parents and political leaders, they are prompting classroom protests. Two years ago a group of students at Whitney Young High School in Chicago who think the tests are overused decided to fail the IGAP — the ISAT's predecessor — on purpose. The students formed Organized Students of Chicago to lobby for less reliance on high-stakes tests. Last year, they organized more than 200 students around the state to protest the pilot version of the Prairie State by intentionally failing. "We think schools should really be about teaching students to enter the real world and think for themselves," www.uis.edu/~ilissues Illinois Issues November 2000 29 says Jeff Orr, a Whitney Young sophomore. "Teaching a kid that everything has only one answer and drilling them on tests doesn't really prepare them for life." Students aren't the only ones objecting to the spread of high-stakes testing. Educators, including the National Council of Teachers of English, the International Reading Association and the National Education Association, have challenged their use. A 1994 study in the journal Educational Policy found that 77 percent of teachers surveyed felt standardized tests are flawed and not worth the time and money spent on them. Yet, because of pressure to achieve high scores, the teachers reported that they often take time away from regular classroom work to prepare students for the tests. "Teachers know where their bread and butter is," says Peter Sacks, the author of Standardized Minds. "One of the effects of high-stakes testing is a dumbing down of the classroom where teaching is by rote. The high-stakes testing regimes are really quashing innovation, and love of learning is being laundered out of the system." This laundering affects everything from schedules to lesson plans to textbooks. In some Chicago classrooms for remedial students one of the basic texts is Taking the (T) error Out of the Iowa Tests of Basic Skills. Bets Ann Smith, an assistant professor of education at Michigan State University, studied Chicago public school classrooms in 1998 and found teachers spending a large stretch of the school year preparing for the Iowa and IGAP tests. "As March approaches and begins, the instructional emphasis of many schools shifts heavily to standardized test preparation, which continues into the spring," Smith wrote in a report for the Consortium on Chicago School Research. "Students often spend a considerable chunk of their day working in test preparation workbooks and taking practice tests." The emphasis on testing can have other effects on students' lives. Last year, scoring mistakes forced more than 8,600 New York City students to attend summer school. In Minnesota last spring, officials told nearly 8,000 students they had failed the state's standardized math test when they had actually passed. More than 300 high-school seniors didn't get their diplomas; some were denied college admission and scholarships as a result. Even if they're scored correctly, testing results don't necessarily give teachers feedback they can use to help individual students, some educators say. Most tests come toward the end of the school year and take weeks to score. "Unfortunately, it's not data teachers can use to impact instruction," says Mary Lamping, director of research and evaluation for Rockford Unit District 205. The Chicago Public Schools and other school districts proudly point to higher test scores as signs their schools are improving. But even when scores rise, they do not necessarily mean students are learning more, critics argue. Test results can be invalidated by teaching so narrowly to a particular test's goals that scores are lifted without actually improving the academic skills that the test is meant to measure, according to the National Research Council's "High Stakes" report. The only independent exam that collects data nationally — The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) — shows that states with intensive high-stakes testing do no better than other states. Out of 17 states — primarily in the South — with high-stakes testing in the mid-1990s, only seven showed gains between 1992 and 1998 on NAEP's fourth-grade reading scores. Ten of those 17 states scored below the national average. On NAEP's fourth-grade math scores, 10 of the high-stakes testing states also fell below the national average. (Illinois is one of seven states that did not participate in the NAEP survey.) Despite America's passion for high-stakes tests, they are hardly the norm in other Westernized countries. "Standardized testing in general is very rare in other industrialized countries before high school," says Monty Neill, FairTest's executive director. Countries such as France, Germany and Japan have high-stakes college entrance exams but don't use extensive testing in the earlier grades, Neill says. Standardized tests can certainly play a role in evaluating how students and schools progress over time. But alternative forms of assessment that measure other, equally important skills such as creativity and critical thinking can be just as valuable if not more so. Rather than instructing students to answer a rigid list of questions, we can be teaching them how to solve problems and quickly adjust their thinking so they can thrive in our rapidly changing world. Many educators suggest students' progress can be tracked by having independent teachers assess their performance on real learning tasks such as writing essays, completing science projects and other evidence of school work. "When looking at kids, we should always use multiple measures," says Marilyn Kulieke, director of research and evaluation for Township High School District 214 in Chicago's northwest suburbs. "You need to have opportunities for students to show what they can do." And yet standardized tests remain politically popular because they are a relatively inexpensive way to say we are moving toward the laudable goal of raising standards. They are cheaper than investing money to alleviate overcrowded schools, put books in libraries, give teachers more training, and add computers to classrooms. "High-stakes testing is about wanting to change schools on the cheap without investing in schools, especially ones serving poor kids," says Neill of FairTest. "This approach enables us to blame the kids, blame the teachers, blame the schools instead of giving them the resources they need." Jon Marshall teaches journalism at Northwestern University and writes extensively about social, political and family issues. His last article for Illinois Issues, "Have we let our children down?" focused on the problems facing our state's youngest residents and appeared in the November 1999 issue. He usually scores well on standardized tests. 30 November 2000 Illinois Issues www.uis.edu/~ilissues |

|

|