|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Spotlight on health care

CRITICAL CONDITION

by Tony Cappasso Three years ago, the governing board of Abraham Lincoln Memorial Hospital in the small central Illinois community of Lincoln could look forward to an operating surplus of around 3 percent. This year, operating expenses at the 66-bed facility will exceed revenue by about 1 percent. In fact, the hospital's governing board had to dip into savings to the tune of $500,000 just to keep the books in the black. The reason for the deficit, says hospital chief executive officer Forrest "Woody" Hester, is sharply reduced payments from Medicare, the federal government's health insurance program for the elderly. Those cuts were mandated by the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, legislation that will carve more than $116 billion nationwide out of Medicare spending by 2002. In 1998, the first year hospitals felt the full brunt of the cuts. Medicare spending at Abraham Lincoln Memorial fell by $500,000, Hester says. By the time the cuts are implemented fully, he estimates the hospital's income will have fallen another $600,000. Abraham Lincoln Memorial's budget problems are mirrored in the bottom lines of most of Illinois' small and rural hospitals, according to Illinois Hospital and HealthSystems Association finance director Kevin Shaughnessy. Fortunately for the Lincoln hospital, its board was able to pump in extra money to make up the Medicare shortfall. Many small and rural hospitals don't have that option, he says. As a result, nearly 20 percent of Illinois' rural hospitals are losing money, even after factoring in gains from the stock market and other investments, he estimates. Illinois hospitals of all sizes have taken a hit from Medicare cuts, certainly, but the state's small and rural hospitals have been put at increased risk for their very existence. "Roughly 64 percent of the state's 200 hospitals are operating at a loss," Shaughnessy says. "Fifteen Illinois hospitals have closed their doors since 1990," three of them in the last seven years. Statewide, the federal budget cuts will take more than $2.5 billion out of the coffers of Illinois hospitals, according to Shaughnessy, with nearly $247 million coming out of the budgets of the state's 70 small and rural facilities. Officials at the Health Care Financing Administration, which runs Medicare, defend the steep cuts, arguing the goal is to "eliminate the fat" from the program and keep it solvent through the year 2025. But hospital officials say the cuts have gone deep into the muscle of services aimed at the most vulnerable patients. Reacting to complaints from hospital officials in Illinois and elsewhere, Congress this year restored a small portion of Medicare funding. The 1999 Balanced Budget Refinement Act increased Medicare payments across the country by around $40 billion, including nearly $20 million aimed at restoring some reimbursements for large urban teaching hospitals such as Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke's in Chicago. Illinois' small and rural hospitals picked up an additional $29 million. In an effort to address further the needs of rural communities, Congress also created a new category called "critical access hospitals," that restored higher payments to hospitals that care for elderly patients living in areas where health care is scarce, according to Barbara Dallas, a specialist in rural health care with the Illinois Hospital and HealthSystems Association. To qualify, hospitals must

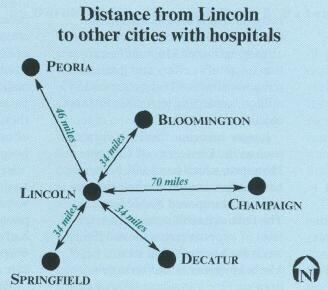

www.uis.edu/-ilissues Illinois Issues November 2000 31 serve on average no more than 15 in-hospital patients per day, average 96-hour lengths of stay and be deemed by the state a "necessary provider." So far, seven Illinois hospitals have qualified for the program. But if the budget cutting continues and the hospital's application for critical access status isn't approved, something at Abraham Lincoln Memorial will have to change, Hester predicts. Even closing the inpatient part of the facility isn't out of the question. "If the hospital closed its inpatient unit, everybody who needs hospital care would have to travel elsewhere," Hester says. That would prove especially hard on older residents of this town of 15,400. The city nearest Lincoln with a full-service hospital is Bloomington, 34 miles to the northeast. Springfield is roughly 30 miles away to the south, while Peoria is about 45 miles to the north. Closing a hospital to inpatient care also would cut into the sinews of the entire community health care structure. Were Abraham Lincoln Memorial to close its inpatient unit, for example, many of Lincoln's 12 full-time primary care and obstetrics and gynecology doctors would probably head for locations with functioning inpatient hospitals, Hester says. "We also have around 30 specialists from Springfield who work in Lincoln part-time," Hester says. "Without a fully functioning hospital, we'd probably lose most of them, too." Outpatient services and home health care also would be severely affected, which again would hit hardest on the oldest and frailest of the elderly, Hester says. Other factors, to be sure, are affecting financial prospects for Illinois hospitals, including the impact of managed care, population shifts and the development of efficient means for transporting sick or injured people to medical centers in larger cities. But there's no doubt that trimming Medicare payments for all levels of services since 1997 has hit hospitals hard. And the pain has by no means been limited to small or rural Illinois hospitals. The federal budget cuts carved nearly $22 million from the bottom line at Memorial Medical Center in the midsize city of Springfield, according to hospital chief executive officer Bob Clarke. By 2002, Medicare reimbursements to Memorial, a 562-bed facility, will have plunged by about $43 million, he says.

The same grim arithmetic holds at St. John's Hospital, a 570-bed hospital that is also located in the capital city. The Medicare cuts have already extracted $16.5 million from that hospital's coffers and predicted reductions by 2002 run to around $45 million, according to Arthur Pittman, chief financial officer. Larger academic medical centers such as the University of Chicago Hospitals, which has 1,031 beds, also have suffered under the belt-tightening regime imposed by Medicare. The federal health agency froze the level of support payments at 1996 levels for hospitals that treat Medicare patients and train new doctors. One immediate effect was that many academic medical centers were unable to increase programs that train residents, medical school graduates who are learning to practice specialty medicine such as cardiology or surgery. Southern Illinois University School of Medicine in Springfield, for example, could train up to 300 residents at Memorial and St. John's hospitals, school officials say. The reality of the freeze, however, is that they get federal support for only 199 resident positions. In fact, the school has about 225 doctors in training at both hospitals. St. John's and Memorial have to absorb an extra $2 million in costs for training these new doctors, according to school officials. Statewide, falling Medicare payments both for in-hospital care and outpatient services to elderly patients will have taken more than $1 billion out of Illinois academic medical centers by 2002, according to Hospital and HealthSystems Association figures. Medicare began in 1965 as a benefit program aimed at making health care more available and affordable for the nation's elderly. But as that population rose, federal bureaucrats struggled to meet congressional mandates to rein in its costs. In 1984, for example, the agency switched from a payment system based on cost to a so-called "prospective payment" method of reimbursement for the in-hospital care of beneficiaries. Essentially, Medicare created hundreds of categories of illnesses for which the agency set fixed payment rates. If hospitals could treat hospitalized Medicare patients for less than the fixed rate, they kept the difference. If the cost of care exceeded the fixed amount, hospitals had to absorb the loss. In the ensuing decade and a half, hospital officials reacted by finding ways to shorten stays for Medicare patients, shifting some care that had once been hospital based to outpatient centers or home health care services. Medicare finally reacted to that 32 November 2000 Illinois Issues www.uis.edu/~ilissues change this year, cutting payment levels in those areas, as well. In August, the agency extended the prospective payment system to outpatient Medicare services. And on October 1, a similar payment system went into effect for home health care. That has forced hospitals to cut back on those services. Behind the statistics are elderly patients whose access to health care services is limited, hospital officials say. For example, Memorial's Visiting Nurse Association of Central Illinois slashed its geographic reach from within 60 miles of Springfield to within 30 miles, leaving the sick elderly in many rural areas with limited coverage, according to the agency's head, Barbara Sullivan. Many of those patients were forced to turn to county public health departments. Hit themselves by the cuts, however, some health departments dropped 24-hour home health coverage, leaving homebound elderly to their own devices, Sullivan says. "Home health care is going to change a great deal," Sullivan predicts. "We're having to teach patients' families and other caregivers to provide some services themselves, while we focus on providing the more high-tech services," she says. St. John's visiting nurses' patient load fell 25 percent from roughly 500 to around 375, the hospital's home health services director Ann Derrick says. In fiscal year 1999, the interim payment system for home health care cost the hospital around $1 million, she says. Memorial will probably come up in the red on home health care services to the tune of about $300,000 over the next year, according to chief financial officer V. Paul Smith. St. John's, too, expects to lose money on home health care under the impact of reduced Medicare funding. Private home health agencies have been especially hard hit by the Medicare cuts. Nearly a fourth of agencies nationwide have closed their doors, and more will likely follow when the full impact of the new prospective payment system hits home, Sullivan says. Indeed, as the elderly population grows, further cuts are inevitable. And services that already operate close to the bone will be hurt the most. That includes hospitals that serve rural communities. "A lot of the smaller operators are getting squeezed out," says Barbara Dallas, the specialist in rural health care. The critical access category that brings with it higher Medicare payments to hospitals will help some small and rural Illinois facilities survive, she says. But it won't halt the loss of some of the hospitals in rural areas of the state. "We're going to see more hospitals close their doors," she predicts. "It's just a matter of time." Tony Cappasso is the medical reporter/or the State Journal-Register of Springfield. www.uis.edu/~ilissues Illinois Issues November 2000 33 |

|

|