|

Cache Incentives

BY BURKE SPEAKER

PHOTOS BY ADELE HODDE

AND CHAS. J. DEES

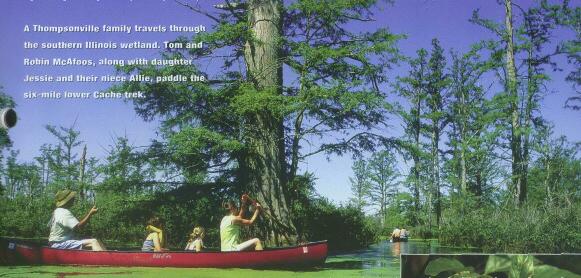

First-time

swamp paddler

stung by ignorance,

not mosquitos,

in an eye-opening

trek down the

Cache River.

The canoe glides through neon-green duckweed on the Cache

River, past cypress trees that are

more than 500 years old.

By the time our canoes edged away from the swampy Cache

River shoreline, skimming through soupy layers of neon green

duckweed, the sun's upward trek had nearly peaked, and I warily began

preparing for an onslaught of plasmathirsty mosquitos. My already sunscorched skin tingled at the thought

of those diminutive parasites plunging microscopic needles into my

arms, legs, neck or any other uncovered extremity. Primed to see a true

swamp in Illinois, an unquestionable befuddlement for those who've traveled the state, I anticipated a day

defending my O-positive supply against those rancorous thistle bugs.

There is little doubt I was naive,

alright, ignorant concerning what

swamps are like. I had bought into

the Hollywood version of dirty

waters, rabid snakes and mosquitos

like watermelons. Still, I was willing

to accept a future ointment bath (also

I had snagged a friend's can of insect

repellent) to paddle a part of Illinois

few realize exists. Living my entire

life in this state, I had not heard of

the Cache until a year ago. Gullibility

had assured me the Prairie State

couldn't possibly house bald cypress,

tupelo gum and an assortment of

swamp critters. This is why, had

there been mosquitos, I probably

would have swallowed most of them

when my jaw fell agape at my first

sighting of Illinois' very own, and

very unHollywood, swampland.

All around me were bald cypress

trees, their trunks dark with moisture

as they leech into the water, sucking

up nourishment that causes such

immense height and grandeur. Their

leaf-adorned branches soaked in the

sunlight and doubled as hostesses for

a slew of chorusing birds that watched

us pass. At the trees' base, the puzzling knee features awkwardly protrude from the water. Dozens of these

dull, wooden daggers surround each

tree's base. It is said they provide stability for the ancient historians, though

to me they appeared as stoic gnomes

huddled together in hushed secrecy,

cloaked in robes of moss.

Being summer, the air stayed

heavy and warm, though a light

wind blew in periodically to cool us

down. After we paddled for awhile,

the bird songs quieted, and the only

sound heard was the inevitable

plunking our duckweed-coated paddles made dipping into the water.

Then, in the distance, a low-pitched

screech echoed across the water, and

a great blue heron swooped silently

behind a transparent cypress curtain.

I stopped paddling to watch, knowing that if any creature demands

respect in this murky land, it is the

great blue. There is something

ancient and elusive in its flight.

Darting above us, chimney swifts

circled the sky, leaving their protected

nests in some hollow cypress to search

out insects. An assortment of waterfowl, including hooded mergansers

and wood ducks, plus warblers, egrets

and turkey vultures, call the Cache

River home. I noticed other strange

birds, and I silently cursed myself for

being so ignorant when it comes to

memorizing different bird species.

|

September 2000 7

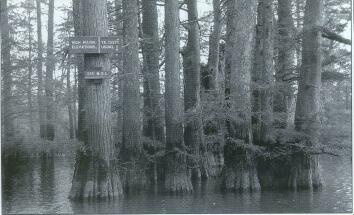

Signs mark the water level

from previous years' floods,

which raised the river high above

its normal range.

|

On top of the multitude of birds,

animal life is equally impressive.

Otters and bobcats are sighted periodically along the Cache, though

they usually remain elusive. Their

home bears a fitting name, for in

French, Cache translates to 'hidden.'

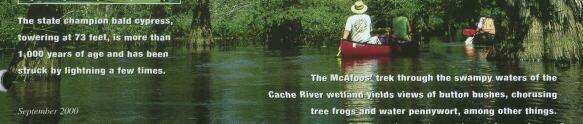

The bow of the metallic canoe

bobbed forward, and our paddles commenced stirring the duckweed stew as

we drifted by post-flowering button

bushes. Paddling was becoming more

arduous as the thick duckweed, layered with 10 different species types,

forced us to slow down and absorb the

scenery. It wasn't too difficult to succumb to this particular demand. The

trek was a path into a fairy tale, another realm I foolishly deemed impossible

to encounter in the corn-besieged flat-lands of Illinois. What made it all the

more magical was the knowledge that

this was an area first destroyed, then

revived, by man.

It is paradoxical to imagine the

mentality of early European settlers

who came upon this wetland more

than 200 years ago. At the time, settlers viewed swamps as filthy places

of disease, and crossing the swamp

meant possible sickness or death.

Cache River Natural Area site superintendent Jim Waycuilis calls the

area the 'Graveyard of the Midwest,'

because of the hundreds of settlers

who died here of malaria. Fearing

that mysterious 'swamp gas' was

causing the disease, and believing

swamps only hampered human

endeavors, the decided-upon

chemotherapy was to exterminate the

swamps. Lumber needs reinforced

the land-clearing desire and beginning in the 20th century the swamps

were drained, and the alien landscape

nearly became another Illinois pasture. The water wouldn't come back

for good until 1982, when two conservancy groups won a court battle to

return the water to the Cache.

Oddly enough, it was later

learned the swamp gas theory was a

fallacy, and science revealed that

mosquitos were to blame for spreading the disease.

I suddenly remembered that I

hadn't been skeeter-attacked once,

nor even seen a semblance of those

little kamikazes. A teal dragonfly

buzzed past the canoe as if on cue;

the secret revealed. With the amount

of dragonflies, frogs and toads in the

swampy Cache River, Waycuilis said,

mosquitos are seldom bothersome to

the paddler. The bugs are terrible

around the marshy inland, but gliding

across the water , not a mosquito soul

could be found.

Not that I would have cared. The

canoeing was

becoming even

more enjoyable,

the soothing river

silence interrupted

|

Cache

River

|

|

only by the call of a great blue heron

or fish splashing in front of the bow.

There were no loud mechanical noises, large crowds or traffic here. It was

noon and the only rush was the wind

occasionally urging us forward. We

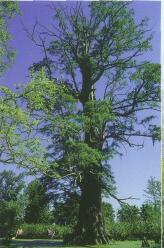

rounded a brushy bend, past more

cypress and approached the state

champion bald cypress, a 73-foot tall

giant more than 1,000 years of age.

The timekeeper was struck by lightning many times, and its top had long

since blown off. Still, it stood mighty

and proud, much to the disdain of the

lightning, I suppose.

Gazing up at the giant provokes

thoughts of what mysteries this old

tree has seen, and what history

occurred under its branches, or

above, for that matter. Most of the

cypress are from 500 to 1,000 years

of age. To put it in perspective, when

Columbus arrived at what he would

call the Americas, many of these

trees were already 500 years old. I

expect the early, indigenous people

canoed this same water, maybe even

stopping for rest beneath what is now

the state champ. After a moment, we

slowly left the regal leader, and its

branches swayed a farewell, always

watching and surveying its domain.

We followed the international

canoe trail markers as the river oozed

along. The Cache, which begins near

Cobden in Union county, was actually

carved out by the Ohio River prior to

it changing course. The 110-mile river

is divided into two unique sections;

the upper and lower Cache. The only

part of the river that can be canoed is

the lower Cache. Canoeing the upper

Cache is out of the question, as severe

bank erosion has left felled trees

impossible to maneuver around.

Looking skyward, I noticed the

sun was dipping lower. We had

canoed three miles into the swamps

Burke Speaker is an intern

serving as a staff writer for

OutdoorIllinois. Originally from

Galena, Burke attends Southern Illinois University, where

he is majoring in journalism.

8 OutdoorIllinois

of the Cache River, and now we

reluctantly paddled back to shore,

worming our way along backwaters

to the main river channel, and finally,

to the dock. Vacating the canoe, I

stretched, tired and sore, but exhilarated. The canoe trip lasted mere

hours, but in that time I had meandered through a landscape that

wasn't supposed to exist in Illinois.

of the Cache River, and now we

reluctantly paddled back to shore,

worming our way along backwaters

to the main river channel, and finally,

to the dock. Vacating the canoe, I

stretched, tired and sore, but exhilarated. The canoe trip lasted mere

hours, but in that time I had meandered through a landscape that

wasn't supposed to exist in Illinois.

Walking back to the vehicle, the

wind ceased, and I could smell the

swampy, damp air. I figured that, as

with many other national and state

natural treasures, man's relationship

with the Cache is one of ignorance,

realization and then, preservation. I

paused at the car door for another look

at the river, and turned to leave, mentally pledging a return visit-minus the

unused can of bug spray, of course.

Walking back to the vehicle, the

wind ceased, and I could smell the

swampy, damp air. I figured that, as

with many other national and state

natural treasures, man's relationship

with the Cache is one of ignorance,

realization and then, preservation. I

paused at the car door for another look

at the river, and turned to leave, mentally pledging a return visit-minus the

unused can of bug spray, of course.

For canoeing or other information

about the Cache River contact the

Cache River Natural Area at (618)

634-9678. The river can be accessed at

the Lower Cache River Access or for

$1 by private boat launch. Canoes can

be rented for $25 by calling Cache

Core Canoes at (6l8) ,845-3817.

September 2000 9

|