|

BOOTLEGGING IN ILLINOIS

bathtub gin and the whole shootin' match

by Nancy Nixon

A squeal of tires and the

roar of engines. Terrified

mothers and children

hide as several men,

dressed in tailored suits,

dark trench coats and fedoras,

wielding machine guns, storm a

warehouse. Gunfire breaks out,

and in less than a minute, it's

all over. The death toll is three,

and two others are badly injured. With their job fulfilled

the men dash to their cars and

speed away into the dark shroud

of night.

For Illinoisans, this probably sounds like the olden days

in Chicago — but gangster activity stemming from alcohol bootlegging operations was just as cornmonplace in downstate Illinois during the Prohibition period.

"There would be no quenching

the insatiable demand for booze in

the big cities, and in many of the

smaller towns too," writes Taylor

Pensoneau, author of a soon-to-be-published book, detailing the activities of notorious southern

Illinois bootleggers, the Shelton

Gang, which will be published

later this year. "For the most part,

though, the far-flung market for liquor-triggered illegal production

and distribution systems blanketed

virtually every part of America.

Lawless or not,

these operations turned

profits like

any other

large business, only often

greater. Of

course, most of

the dough

ended up in the pockets of

organized crime, which

wound up pretty much running the whole illicit show."

The 18th Amendment to the

U.S. Constitution, which was

ratified in 1919, prohibited the

manufacture and sale of alcohol.

10 ILLINOIS COUNTRY LlVING•April 2001

The gross neglect of enforcing the

Amendment gave widespread, illegal bootlegging carte blanche

throughout Illinois. Many a farmer

and businessman made his own

private stash of "bathtub gin," as it

was called, but that wasn't where

the money was. The allure of the

profits from large scale

bootlegging, or the illegal

manufacture, transportation or distribution of

alcohol, fostered the

development of a new type of criminal,

the gangster, which

led to more than a

decade of turf wars and

murders. "For the Sheltons, for AlCapone in Chicago, and for many

others, Prohibition was their gold

rush," writes Pensoneau. And this

set the stage for one of the most intriguing periods in Illinois history.

Chicago was the headquarters

for the illicit bootlegging activity of

mob boss Al Capone and his gang.

He held a tight rein on any buying,

selling or transporting of alcohol

in a territory that reached southward to just below Peoria, and

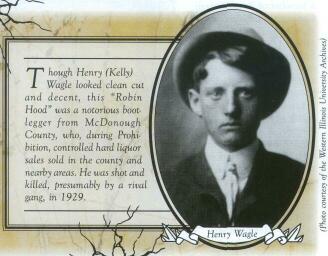

sometimes further south. Henry

"Kelly" Wagle of Colchester,

known as the most notorious man

in McDonough County, supplied

most of the hard liquor sold in the

county and nearby areas. Wagle

was acquainted with Capone and

hauled his liquor from Chicago.

Wagle, like many bootleggers,

was considered a sort of "Robin

Hood." While he was a known

bootlegger, that was overlooked to

a degree because he also did good

deeds for the local people and

helped to keep a lid on petty

crime. But, he was also quite bold.

One particular story details that in

1926 or 1927, the Christian

Church in Colchester converted

from coal to oil heat, leaving a

large coal bin empty in the basement. Supposedly, Wagle acquired

access to the bin and stored liquor

there. Once the rumor got out, of

course, the liquor was removed.

The Ku Klux Klan waged a war

on bootleggers. The Klan had been

formed with a common purpose to

bring back what they called "decency" and to rid those engaged in

"improper behavior," using whatever tactics they felt were necessary.

Although they had the support of

many churches, they abhorred foreigners, Jews and Catholics. The

Klan had grown to some

200,000 by the mid-1920s, and was gaining

power in and around

McDonough County.

The Klan was a constant

thorn in Wagle's

side, and he even

had a cross

burned on his

property one night.

On April 8, 1929

Wagle was shot and killed gangland style, or "with his boots on,"

as it was called. Although his killer

was never found, it was said that

Wagle's murder was most likely ordered by a rival gang.

Located around 30 miles south

of Colchester, the small town of

Beardstown was known as a refuge

for gang members who needed to

leave Chicago "in a hurry" during

the Prohibition days.

"I lived in Beardstown from

1921 on and it was pretty well

known that many bootleggers in

the Al Capone era came down

when the heat was on," says Pharmacist Ed Lewis, now a resident of

Canton. "They lived on houseboats on the Illinois River and

they had unusual built-in burglar

alarms. When the frogs stopped

croaking, they knew someone was

approaching."

Lewis continues, "The gangs

would take anywhere from a two-

week to a month-long vacation and

enjoy the local sports of fishing

and duck hunting."

Morris Bell, a former board

member of Menard Electric

Cooperative and the Association of Illinois Electric

Cooperatives, backs up

that story. "Locals known as 'pushers' would take Al Capone and his

people out to the prime hunting locations in the area around Snicarte

and Bath and teach them how to

hunt. If the gang members didn't

shoot any ducks on their own, the

pushers would kill some so the

gangsters could go back to Chicago

and gloat about their 'catch.'"

Frank McErlane, known as the

meanest gangster in Chicago and

loyalist to Al Capone, actually died

in Beardstown. After Capone was

sent to prison, McErlane became a

drunk, and his south side Chicago

associates, fearing for his life, arranged for him to live on a lavishly

furnished houseboat on the Illinois

APRIL 2001•

ILLINOIS COUNTRY LIVING

11

River. Unlike most of his gangland

associates, McErlane died "with his

boots off' on October 8, 1932 at

Beardstown's Schmitt Memorial

Hospital. After a rather unceremonious funeral (by ganster standards), he was buried

Sepulcher Cemetery in Chicago.

Many a poor

farmer turned to boot

legging as a source of

income. Auburn resident Felix Marchizza,

a member of Rural Electric

Convenience Cooperative,

Auburn, was born and

raised in southern Illinois'

Franklin County, and remembers bootlegging well. He says

that in the 1930s, he was a

young boy in about the second

grade. His dad was a coal

miner and the family barely

lived from day to day, so bootlegging kept food on their

table. Once, when an officer arrested him and threatened to

put him in jail he retorted,

"You can do that, but you'll

have to feed my family."

"My dad did a lot of bootlegging," Marchizza says. "We

kept the still in the shed or in

the basement, depending on

where we lived at the time." He

adds, "My dad's buddy had a

big still set up in his barn and we

sold moonshine to the Mafia in

Chicago. They bought it a truckload at a time. They'd come down

south in their Model T- and Model

A-trucks, and men with machine

guns would stand guard while they

were loading up."

When asked what he thought

of the Mafia back then, Marchizza

replies, "Heck, we couldn't wait for

them to come. We were so poor we

couldn't afford to buy candy, so

whenever they came down, the Mafia members would bring all the

kids candy."

Phillip Trammel, a resident of

Stonefort, in southern Illinois, can

also remember bootlegging in his

area. He says one of his neighbors

had seven stills that were kept in

the basement, and when he died,

they were auctioned off illegally.

He had another neighbor who

made his own wine and used it to

pickle his beets. "Those were the

best beets I ever ate," says Trammel.

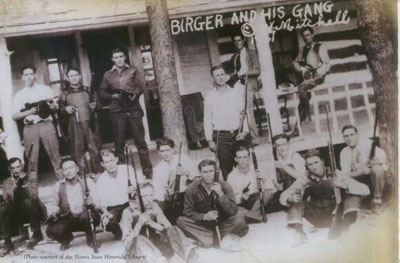

For a number of years, during Prohibition, southern Illinois was the battleground

between warring bootleggers, the Shelton Gang and the Birger

Gang.

Like Marchizza and Trammel, the

Shelton brothers were also

raised in southern Illinois.

Of the five brothers, only

three, Carl, Earl and Bernie comprised the Shelton Gang. After

stints in prison for various crimes,

Carl and Earl worked in Illinois

mines and with Bernie, they returned to East St. Louis, where

they had previously worked, and

began running lucrative gambling

houses and bootlegging establishments. In the early 1920s their

bootlegging operation expanded

into the southern Illinois counties

According to Pensoneau, Carl

Shelton supposedly said, "There

ain't a little town around here

that's not gonna miss its whiskey.

These farmers may vote dry on

election day, but they drink wet on

Saturday night. We can run

enough rum up here from the Bahamas to flood all of Little Egypt

(southern Illinois)."

In 1923, Carl Shelton met

Shashna Itzik (Charlie) Birger, a

Russian Jew, in a Herrin hospital,

and they became personal friends

and business associates in

both bootlegging and the slot-machine racket, which they all

but monopolized. They

teamed up against the Ku Klux

Klan, who by then had overwhelmed the area. This relationship would be short lived,

and in fact, their feud would

become one of Illinois' great

rivalries of the Prohibition era.

It all started when Earl

Shelton learned that Charlie

Birger had milked $3,000

from their joint 50-50 slot-machine partnership, for his

"protection." The Shelton

Gang felt betrayed and banished Birger from the business. At around that same

time, Birger became enraged

when the Shelton brothers

wouldn't help smuggle some of

his Russian relatives into

Florida.

The loyalty the

two gangs had once

enjoyed was now replaced with mistrust and

disdain, and from that

point on it was war, with

bombings and shootings a

regular occurrence. Both

gangs operated from behind an arsenal of ammunition. There wasn't

a safe place in southern Illinois

during the war between the two

gangs. If innocent by-standers happened to be at the wrong place at

the wrong time, they could be

caught in the line of fire and killed

along with the intended targets.

The Shelton Gang didn't have a

fixed headquarters, making them

harder to locate, but Birger had a

lavish roadhouse, known as Shady

Rest, where "bathtub gin flowed

like water," which was their rival

12

ILLINOIS COUNTRY LIVING•

APRIL 2001

gang's favorite target from land

and air.

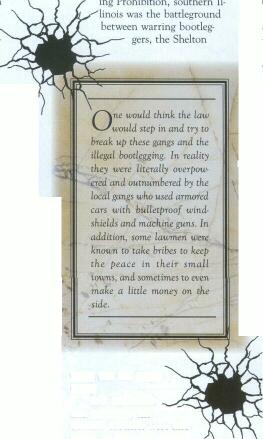

One would think the law

would step in and try to break up

these gangs and the illegal

bootlegging. In reality they

were literally overpowered

and outnumbered by the local gangs who used armored

cars with bulletproof windshields and machine guns.

In addition, some lawmen

were known to take bribes

to keep the peace in their

small towns, and sometimes

to even make a little money

on the side.

If one of the gangs antagonized the other, the rival

gang would take revenge,

and vice-versa. As soon as

Birger would make a liquor

delivery to a roadhouse (illegal drinking establishment),

the Shelton gang would

come right after him and

shoot up the business.

Birger would retaliate, and

this violent bombardment

became a way of life in

southern Illinois. The gang

war escalated when, on November 9, 1926, Birger's beloved hideout was thought

to have been bombed and

destroyed by Shelton's men, leaving only smoldering ashes and four

charred bodies in the aftermath.

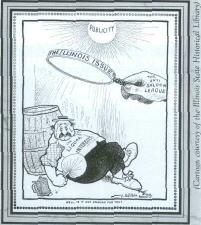

This Cartoon depicts the great

pressure exerted by the anti-alcohol faction over the manufactures and distributors of alcohol, which resulted in the

18th Amendment to the Constitution, known as Prohibition.

|

Birger swore revenge, and his

final act against the Shelton Gang

was to have Joe Adams, the mayor

of West City, and a Shelton sympathizer, murdered. Birger was tried,

convicted and sentenced to hang

for the murder. Although Birger

was a vicious killer who would take

a life in an instant, he was beloved by the locals, who appreciated his acts of generosity and

local protection. On April 19,

1928, as he was being led to the

gallows, Birger calmly smiled,

shook the executioner's hand and

was quoted as saying, "It's a beautiful world."

Shortly after Birger's death, in

1933, the Prohibition Amendment

was repealed and alcohol

flowed legally again, putting

most bootleggers out of business. The killings continued,

however, as nearly 50 members of the Shelton Gang

were either murdered or

died under inexplicable circumstances within a 20-year

time span.

Today, some evidence of

the Prohibition era still exists in Illinois. Bootlegging

continues in some areas of

the state, while some counties are dry, meaning alcohol

can't be sold there. And

some people are hesitant

even today to speak freely

about the bootlegging activity that occurred in their areas. Pensoneau says, "There

is still lingering apprehension in some places about

these scenarios played out so

many decades ago."

We can only speculate

about the stories that

were carried to the

grave with those who

lived and maybe even

took part in the illegal activities back then, but we do

know one thing. The Prohibition

era has indelibly marked a compelling and mysterious chapter in the

book of Illinois' history.

|

More information about Prohibition and bootlegging in Illinois can be found at the Illinois

State Historical Library, Old State Capitol Building, Springfield, Illinois, 62701, (217)

785-7955; the Western Illinois University Archives, at (309) 298-2717; and at several Internet

web sites: www.britannica.com; encarta.msn.com; www.americanmafia.com;

www.egyptianaaa.org/SI-History3.htm; www.springhousemagazine.com; www.hallmemoirs.com.

Books relating to the subject are: The Bootlegger, by John Hallwas, The Era of Excess, by

Andrew Sinclair, Prohibition: The: Lie of the Land, by Sean Dennis Cashman, and Taylor

Pensoneau's book about the Shelton Gang, which will be completed later this year. Pensoneau

can be reached at the Illinois Coal Association at (217) 528-2092.

|

APRIL 2001•

ILLINOIS COUNTRY LIVING

13

|