|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Chicago's

Paul Barrett Historical Research and Narrative Today, public transportation is often talked about as a problem, or a crisis, or at best as a kind of back-up system for the automobile in bad weather. More often than not, transit is seen as a "special interest" issue of the poor on one hand and downtown business and tourist interests on the other. In fact, mass transit is very important to major cities in the year 2001. For seventy years or so between about 1880 and 1950, public transportation was the only reliable transportation for most Chicagoans and probably for the majority of suburbanites. Railroads had created a big city in Chicago in the 1850s where only a large town had existed before. By 1856 four railroads had what would later be called "suburban commuter stations" near the city limits (well within what is now the city). Beginning in 1858, Chicago copied other, older cities and began to extend "franchises" to private companies that proposed to build "street railways" in major streets and out into what were then "the suburbs" (three to six miles from the center of town). Though at first these horse-drawn vehicles reached only relatively affluent areas, by the 1890s public transit had become a central element in political debate as well as a part of daily life for many middle-class people and a few of the working poor. In that year, the "average person" rode mass transit 164 times per year; of course, little children and very poor people rarely rode at all, but this number suggested that about one-third of Chicago people were regular riders. By 1916 the same "average" Chicagoan rode 341 times per year. In the years between 1880 and 1920, public transportation in Chicago underwent—and

25

helped cause—a number of revolutions. In 1880 (as in 1860) the mythical "average" Chicagoan lived about 1.5 miles from the center of town—not much further out than in a small town today, even though there were more than 800,000 people in the city in the latter year. By 1910, the "average" person lived about 4.5 miles from the center of town. And Chicago had a lower population density than any other big city except St. Louis, Detroit, and Buffalo. Annexations and the movement of industry to the edge of the city helped create this dispersion. In fact, in the 1910s, all but a few poor factory workers lived within walking distance of their jobs. But the availability and speed of public transit were also very important. A horse-drawn streetcar could go two to three miles an hour at best. Its main advantage was that steel wheels on steel rails created very little friction, so one or two horses could pull much heavier loads than they could in a vehicle that rode on the bumpy pavement (or in most of Chicago, the dirt and mud). Starting in 1882 cable cars (like those of San Francisco) raised the maximum speed of travel to 10 to 12 miles per hour, not counting the ever-present traffic stops. Electric-powered streetcars came to Chicago in 1890. (Elgin, Rockford, and other Illinois cities were ahead of Chicago in this because their companies had not invested in the hugely expensive cable-car technology). Early electric street cars could go 15 miles per hour, and by 1910, Chicago had streetcars capable of 35 to 40 mile per hour speeds. The realities of traffic kept speeds down to about 11 mile per hour—not much slower than in 1999. Elevated railroads (begun in 1892) could move more swiftly. They averaged about 13 miles per hour with stops in 1910. But the key fact was that a person could live five miles from where he worked and still spend only half an hour commuting every day. Hence, middle-class neighborhoods like Woodlawn, Lawndale, and Lakeview developed around the city wherever the elevated railroads went. In many places, for instance on the Southwest and Northwest sides, better-paid workers spread out and created new neighborhoods along the major surface streetcar lines. This revolution in the way people lived could not have taken place without a series of major political changes. The technology itself was not enough. To understand how public transit and politics changed the city and each other, we have to go back to the beginning again. From the first, streetcar companies were operated to make a profit. But from the first they also had a list of duties that most companies, including "utilities" like gas and electric companies, did not have. This was how the city council wanted it in 1858, and it continued to want this through the early 1940s. Streetcars ran in streets, so the city council required the streetcar companies to pave the streets they ran on, and to remove the snow and (later) spray salt in the winter, sprinkle water to hold down the dust, and take away dirt (mainly horse-droppings) all year. Along with a list of other lesser duties, they also had to provide free passes to police and fire and some other city employees.

All this was a part of the "official" price the companies paid to run streetcars in the streets (elevated railways after 1892 paid a flat fee: after they were defined by the courts as regular railroads, to be protected by a state regulatory commission). But for practical purposes, streetcar and elevated companies were not regulated before 1907. Instead, the surface companies had twenty-year franchises—often one for each street they ran on. In theory, at the ends of these franchise periods the city council could demand better service or some other concession in return for renewal. And it could ask similar concessions when a company wanted to extend its lines. In reality, what many council members asked for in the 1880s and 1890s were bribes (either money or jobs for patronage workers.) Several aldermen made a specialty of "fixing" bribes for utility franchises. John Powers was probably the most famous of these men. This sort of environment meant that honest business people found it difficult to run transportation companies. The streetcar system that covered most of the South Side stayed in the hands of Chicago business, but by the mid-1890s most of the lines on the West and North sides as well as much by the elevated railway were controlled by a financial manager named Charles Tyson Yerkes, the man who had built the streetcar system of Philadelphia and would later finance the subways of London. Yerkes was especially adept at working with political opportunists—widely seen in the late 1800s as "crooks." But the other transit operators simply did what he did, only in less obvious ways. 26 Broadly speaking, companies tried to get their bribe costs plus other expenses back by cutting costs or finding ways to raise fares. Streetcar and elevated fares were set by law and custom at 5 cents per ride. So Yerkes in particular simply strung streetcar companies together (at one time he owned seventeen). A person traveling six miles might have to change cars—and companies—three times. So they would pay 15 cents, not five. Another way to make back bribe costs and "get ahead" was to keep service and repairs at a minimum. This meant crowding and accidents, the latter especially in the cable-car era when a worn or knotted cable could lead to a multi-car pileup as each car slammed into the one in front of it, or a complete loss of service when a cable broke or (later) when electric wires fell. Still, cost cuts were the basic alternatives to price increases for streetcars and elevated companies alike. One other option (selling more stock than the company was worth) was widely practiced, but it could not really produce a long-run income increase. By the 1890s, with most streetcars and all elevated lines running downtown, crowding and accidents (like people walking in front of a trolley or falling off open streetcars) were close to inevitable. But the companies were connected with political corruption, and many middle-class people depended on mass transit and experienced its discomforts every day So the transit companies came to be hated in a way that is hard to understand today. In the period 1893 to 1907, this led to a series of political wars that changed mass transit and the city In the short run, transit became more efficient and better regulated. But in the long run, the events of this 15-year period put public transit out of business as a profit-making venture. Beginning in 1893, the year of the great World's Fair in Chicago, lawyers and business-people, real-estate interests, and most newspapers began to organize a drive to "clean up" local transportation. This made a strange sight, because many wealthy business interests were pitted against other wealthy people (Yerkes, but also some bankers and investors). It is revealing that labor unions and ethnic organizations played only a limited role in this contest. They did not have much influence in the first place, and few black or immigrant workers used public transit on a regular basis. The fight was between one part of the upper and middle class and another.

This was a fight of "legitimate" business against "corruption and mass-transit bosses." The most prominent organization in this fight was the Municipal Voters' League, a combination of lawyers and newspaper people who dug up the voting records of aldermen and, at election time, led publicity campaigns against any alderman who had voted for a Yerkes franchise. They advertised in general and ethnic newspapers and also organized torch-light parades and rallies. The important things to note here are that the reformers focused the public's anger on Yerkes as a person—and an "outsider" from the East—and that the people leading the fight for transit reform were mainly people whose businesses were especially dependent on mass transit: real-estate developers, downtown retail merchants, and newspapers that depended on advertisements from both. Of course there was plenty of real corruption to clean up, and plenty of real improvements were needed. Yerkes and his allies argued truthfully that they had built more than 50 miles of new transit lines every year for fifteen years, and that the average speed of transit, especially the new elevated railways, was greater than ever. On the other side, it was next to impossible to ride a streetcar across Chicago without changing cars several times. Some major lines, like that on Halsted Street, just stopped at river bridges where passengers had to get off and walk across the river and pay another fare. Advocates of the poor, like Jane Addams of Hull House, argued that bad transportation divided the city and kept the poor from getting better jobs. The 10-cent minimum transit fare, was roughly an hour's wages for most "unskilled" workers. Middle-class people were more offended by the crowding and by the perception that Yerkes had created a monopoly. This "monopoly" idea took on form when Yerkes bought up "frontage consents" and began to build the Loop "El." After it was done in 1897 all the elevated companies of the city, even those not owned by Yerkes, would have to pay him a fee to get their trains downtown.

27

Yerkes became known as a "robber baron," a kind of extortionist. After a long series of fights in aldermanic elections, by 1896 Chicago had a city council that was either "clean" or frightened into washing its hands, and a new mayor, Carter Henry Harrison II, who wanted to make a reputation as a reformer. Seeing the proverbial handwriting on the wall, Yerkes (and his Chicago allies) went to Springfield and bribed the state legislature to pass legislation. The resulting "Allen Law" permitted the city to grant a fifty-year franchise to street railway companies. Yerkes seems to have hoped to solve the political problem with one great onslaught of bribery at the local and state levels. And, he could reasonably argue, once politics was out of the way, he could get cheaper credit and build the better system everyone was clamoring for. Reformers were not having any of this, and even the aldermen who were not "clean" or "scared clean" were not too anxious to let mass transit out of their control. The state law passed, but when Yerkes and his allies tried to get a fifty-year franchise through the city council, their drive stalled. On a snowy night just before Christmas 1897, a largely middle-class mob surrounded City Hall and a similar crowd packed its galleries as the council prepared to vote on the fifty-year deal. When any alderman spoke in favor of the bargain, people dangled ropes with nooses over the edge of the gallery and shouted "Hang him! Hang him!" There was no real threat of violence, but Yerkes' allies got the point, and were meek and silent when Carter Harrison's allies had the measure sent to an obscure committee to die. This began a classic example of what would later be called "Progressive Reform." Yerkes eventually sold his companies and left town. But the "winners" had no clear agenda other than being rid of Yerkes and his bribe-taking allies in the council. Between 1897 and 1902 the "clean" aldermen and their mayor, Harrison, bounced the "transportation problem" back and forth. Bankers and investors told them that without higher fares and longer franchises no one would invest in mass transit. They also claimed that if people could transfer from one streetcar line to another, the companies would go broke because their "take" in fairs would be cut by 1/3 to 1/2. But the reformers had promised to "solve" the "transportation problem," not just to get rid of one man from Philadelphia. In 1902 they tried to find another classic "Progressive" solution. They hired a well-known civil and electrical engineering expert, Bion J. Arnold, to study the entire problem and take the hot potato off their hands. Could subways be built in Chicago, they asked? That was a good engineering question. But they also asked the engineer whether streetcars could make money if all lines were run as one system with free "universal" (everywhere) transfers. This was a business question and a question of social policy, but Arnold agreed to take it on as well. At the end of 1902 he came back with an elaborate study showing who rode where and what it cost to run a streetcar system. The subway question was an easy one, but he answered it with a plan for streetcar subways under the Loop and cross-town in Halsted street, a mile west of the center of town. He also suggested ways to link suburban commuter railroads via downtown interchanges

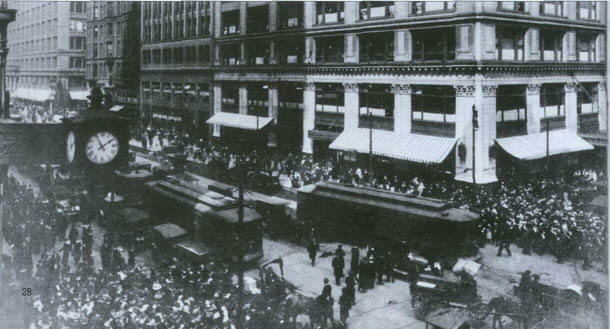

Chicago, State and Madison Streets, c. 1910

28 and perhaps a tunnel. On the transfer issue he was almost eloquent. "Chicago is one city," Arnold wrote. Its people had the "right" to travel all around it, and the economic way could be found through a rather complex transfer system. Though it seems obvious in 2001, the idea that Chicago was "one city" was almost radical in 1902. His studies of other cities show that Arnold knew he was striking at class and ethnic divisions, not just streetcar companies. But the bankers in New York and in Chicago remained unconvinced. Between 1902 and 1905 the new owners of the Yerkes companies (and the old owners of the South Side lines) refused to replace cars or make improvements. They could not get money from banks, they claimed, because many of their 20-year franchises had expired. But the Council did not dare give a franchise to anyone in the transit business until it could at least give the appearance of solving the "transit problem." The engineer, Arnold, had not gotten them off the hook, he had gotten them on another, worse hook by showing how much was possible. For two years (1905-1907) this led to a situation in which Progressivism seemed to destroy itself, and a mayor with "radical" ideals tried to run the city. The "radical" was Edward Dunne, a former judge who believed the answer to the transportation problem was city ownership. The city, he argued, could use its own credit to buy equipment and improve the system. Service, not profit, would be the main force in transit policy and, Dunne argued, the city would have to perform well because the voters would be watching it. Most of Dunne's two-tear term was eaten up by this issue. Business and the press, who had so hated Yerkes, hated "municipal ownership" even more. In 1905 the idea that socialism might be adopted by whole countries or even "take over the world" was very real—at least in the minds of conservative businessmen. Letting government run a profit-making business looked like the first step toward some sort of Marxist inferno. In vain Dunne and his allies pointed out that cities had long run schools, sewers, and water plants—anything that did not make money. Opponents cited corruption in other public service systems, and the streetcar companies let service deteriorate further (while the state-regulated Elevated lines bought hundreds of new cars). By 1906, many people had swung back to the idea that some kind of compromise with the companies and bankers was inevitable. Compromise was what happened, and this compromise helped make mass transit a long-term disaster in Chicago and many other cities that made similar compromises. Originated in the city council and passed over Dunne's veto, this compromise was phrased in complicated language that has to be dealt with if the deal is to be understood. First, all the companies got a 40-year franchise—twice the usual term. Companies (really the banks that invested in them) were guaranteed a "reasonable return" on the bonds and other securities they accepted from the companies. In 1907 such a return would be about 5 percent. All profit above this was to be split with the City, with only 45 percent going to the companies. The City promised to use its share to build subways for streetcars or (as a concession to the remaining municipal ownership advocates) to help purchase the companies at some future date. On the service side, the companies agreed to broader transfers and eventually (1914) to operation of all the lines by one "operating company" and free transfers good everywhere within one hour. Chicago voters ratified this proposal at the 1907 mayoral election by a margin of about 3 to 2. Dunne lost the election to Republican Fred A. Busse.

In the first twenty years under this agreement, between 1907 and 1926, the streetcar companies united and largely kept their end of the bargain. Almost 100 percent of their equipment was replaced, lines were united, and, in the 1920s, schedules were so well synchronized that downtown traffic lights could be timed to the trolley traffic without slowing down other traffic. There were many problems, but this part of the deal seemed to work well. Ridership soared to 1,517, 510,661 in the peak year of 1926, with over 280 rides per citizen for the streetcars alone (counting the El and an independent bus system, annual ridership approached 400 excursions per person). Chicago's equipment was not always the newest, but scheduling and maintenance practices were, and many people born around 1900 remembered the 1920s as a time when the streetcar was better transportation than the automobile. In part they were just recalling that they had been happier when they were young; but in fact, with poor streets, trolleys probably were more swift and efficient than autos for most trips well into the 1930s. But the negative consequences of the 1907 compromise were immense. First, rapid transit was left out, though it carried about 12 percent of the city's traffic through the 1940s. Second, in 1917 the state authorized a bus company, the Chicago Motor Coach, to serve the city's boulevards and park roads, where streetcars were not allowed to run. So, after 1917 there were three competing systems taking revenue from one another. The Rapid Transit and the Motor Coach were regulated by the state. Chicago could regulate only the track-bound surface streetcars. The city tried in 1911,1916,1923, and 1929 to get the companies together and to build a major subway system for rapid transit and streetcars alike. Elaborate engineering

29

plans were drawn. The last three would have united the West and South sides of the city to the North as never before. But all these plans failed. The engineering was perfectly good, but after 1907, no major investor would put large amounts of money into Chicago transit unless the city gave up its share of the profits, gave an indefinite term ("perpetual") franchise, and allowed fares to rise to meet inflation. After about 1915, most city officials wanted to meet these terms, but their political enemies always successfully accused them of selling out to the "Transit Companies." In an extreme but typical Chicago episode a mayor (William Hale Thompson) whose main financial backer was Samuel Insull, the new owner of the combined Elevated Railways, sued the El when it tried to raise fares after the 1917-1919 inflation of World War I. Insull and Thompson knew very well that this was a hoax, but most voters probably did not. By the mid-1920s matters were so confused that the major bankers that controlled the streetcar lines actually wanted the city to buy them out, despite record business. Again, however, the public refused to pay the bankers "book value." In short, despite the best planning, progressive reform stopped transit improvement from about 1925 to 1947. And while all this was going on (really between 1906 and 1930) the city spent almost $400 million on roads and streets that benefited only the automobile. By 1945, after ten years of depression and five years of war (when few supplies were available), downtown business and most of the transportation company bankers were desperate to get the transit lines into the hands of the city. This turnabout occurred because all the companies went broke in the depression; because, beginning in 1944, the federal government had committed itself to a major superhighway program; and, in very simple terms, downtown and Chicago business was afraid that most retail business and much of the middle class would move to the suburbs. The issue was complicated by the fact that the streetcar companies had made good money in World War II when automobile gas and supplies were rationed. In 1945 and 1946 they ordered a huge fleet of new streetcars, their first big equipment purchase in twenty years. So the streetcar company owners demanded a high price for their property, and negotiations dragged on and on until the state stepped in. Illinois created an "autonomous" agency, the Chicago Transit Authority, to buy and run the whole transit system. Control was divided between city and state, but mayor Edward Kelly and later Martin Kennelly dominated it. Combined with federal aid in building two downtown subways (1938-1951), this made much new infrastructure possible.

On a material level, this change was really necessary. In 1947 most streetcars were close to forty years old and most elevated cars, made of wood, were between 45 and 50. (Imagine a transit system today whose equipment dated to 1950 or 1960). Elevated cars were not just old: they were so little maintained that the air compressors for their brakes had to be kept running night and day because the brake hoses leaked so much that if the compressor motors were shut off, they could never again build up enough pressure to stop a train. This is only one item on a long list of 1947 "transit horribles." But the CTA carried with it a new set of problems. Required by its charter to pay off old debts above all else, the CTA started off with a huge economy drive combined with modernization. Between 1947 and 1958 all streetcars were eliminated (and 700 new ones scrapped or turned into El cars) because busses had a lower overhead cost (no track or wire) and trolleys got in the way of automobiles. In the same ten years, about sixteen miles of elevated in the inner city were abandoned and demolished. Much of this, like a line to the South side's Kenwood or the West side's Humboldt Park, could definitely be used today, though hindsight is always perfect. Most important, the CTA was expected to "break even" on its operations. This rule helped hold back service improvements and encourage service cuts, which drove more and more people to use autos. By the time a real form of public ownership was created in the 1970s (the Regional Transit Authority, "RTA"), mass transit was again a political rather than a planning issue. It is always easy to guess what could have been done better in the past, so we may as well do it. If public transportation in American cities had been allowed to operate like any other business—say, a major grocery store that has competitors and can set its own prices—it might well have done much better. If it had 30

been taken over by the city one hundred years ago when it was profitable, that too might have worked. In each case there would have been someone with a strong incentive to improve it. What happened was that streetcars (the transit that carried about 85 percent of riders in the 1940s) were made into a public utility like gas and light but regulated much more heavily. For example, in 1926 the streetcar companies had to do more than $7 million of public benefit work such as street paving, cleaning, snow shoveling, and providing free rides for police and other city employees. Added to city, state, and federal taxes, this was money paid to the companies by riders but spent for "non-transportation" purposes. In addition, the streetcars faced competition from the El, busses, and autos driving on state, city, and federally funded roads. What used to be called "socialism" might have worked. Real free enterprise might have worked. So might the sort of safety regulation we use for airlines. But the strange formula created by Chicago's Progressive era reformers and used around the country did not work. Instead it may have contributed to the decline of public transportation and to the triumph of the automobile.

Chicago, looking west on Addison Street at Federal League Park (later Wrigley Field), May,15, 1915

Click Here for Curriculum Materials

31

|

|

|