|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

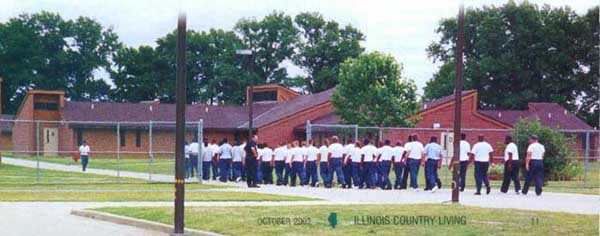

There's a modern day fortress in many communities that's a mystery to most people. Kept away from the mainstream of society, it's segregated by razor sharp twisted and gnarled barbed wire, and monitored by the wary eye of vigilant guards who peruse every movement from tall towers. The daunting appearance of prisons, and the negative portrayal by movie producers and the media might make someone wonder why anyone would want a prison in their back yard. A tour of the Centralia Corretional Center in Centralia reveals a very different viewpoint. At first glance, one would think this was just an average college campus or military base. You'd never know the facility was 22 years old. Devoid of dust, or any debris for that matter, the buildings are absolutely spotless. The floors are polished to a high sheen, and the grounds are beautifully manicured and landscaped. Tidy housing units are scattered throughout the prison grounds. It's eerily quiet, with no loud talking or laughing. Inmates and staff treat one another with respect, and inmates are moved from area to another in orderly lines. This really doesn't sound like a prison, does it? It doesn't, and the Illinois Department of Corrections (IDOC) likes it that way. Most prisons do what they can to be good neighbors to their communities and stay "out of sight and out of mind." The best way the prison can be neighborly is to be as safe and secure as possible. IDOC has instituted a "no tolerance" rule, which has helped to keep inmate disruptions to a minimum. In other words, inmates aren't allowed to "step out of line." There is no tolerance for fighting, arguing, talking back, littering or contraband. Basically anything that's considered unacceptable on the outside of the prison is unacceptable on the inside. As Centralia Correctional Center Warden Bob Bowen strolls about the grounds of the medium security prison, he speaks to many of the inmates by name. That's pretty impressive given that he's only been Warden there for three years and there are more than 1,500 inmates housed there. They, in turn, speak to him as well. Rather than intimidation, which might have been a factor in years past, there is now a sense of mutual respect among the inmates and Warden. Although Bowen seems mild mannered enough, there is no doubt that he could jump to action if necessary. In his 15-year prison career, Bowen says he's never seen an altercation between two inmates or between a staff member and an inmate. Inmates are painfully aware that the penalty for defying the "no tolerance" rule is an extension to their sentence. Amidst this year's Illinois state budgetary woes, the IDOC is experiencing cutbacks and prison closings. Despite these issues, prison security cannot and will not be compromised. According to IDOC officials, the state's prison inmate count is down, and there is space to move inmates from closed prisons to other facilities. Centralia is carrying a full capacity of inmates, so it shouldn't be affected in that respect. But, the early retirement program and some layoffs due to the budget cuts will impact the facility. Bowen and the other Illinois prison wardens have been saddled with the task of making up for those staff shortages. When people leave, they take years of knowledge and experience with them. Bowen says, "Weeks have been spent determining how we'll be allocating staff and where we're going to put people to maintain safety." Bowen's motto for corrections is, "boring is good." And boring means an incident-free prison. He plans to keep it that way. Although communities are aware there are some downsides to acquiring a prison in their areas, they want and need them for 10 ILLINOIS COUNTRY LIVING www.aiec.org

their economic impact — jobs, tax base, retail trade and housing. Keeping a prison in top performance shape requires an abundance of employees working 24 hours a day, seven days a week. At Centralia, $20 million of its $30 million budget consists of salaries for nearly 400 employees, who work with the 1,532 inmates there. And that money is funneled right back into the local economy. Not only do prisons offer some of the most secure and highest paying jobs in the county, their benefits are excellent. So good, in fact, that people generally drive within a 40-mile radius to work. In one case at Centralia, an employee travels daily from Cairo, which is more than 120 miles one way. According to Bowen, the best part of working at the prison is the people. He says that he enjoys coming to work every day. "We have an excellent staff with a strong work ethic. I believe that to be consistent with any rural area. They come to work, want to do their job, then go home and coach their kids' ball teams." Another way the prison affects the local economy is in the sheer volume of products the prison buys from local vendors. Though the list is long, a few items purchased locally are eggs, candy, construction materials and electricity. And the prison contracts several construction companies and contractors for its projects. The prisons electric supplier is Clinton County Electric Cooperative (CCEC) in Breese, and that's good for two reasons. CCEC supplies electricity to its local members, and it's a new member of Southern Illinois Power Cooperative (SIPC) in Marion. SIPC, a generation and transmission cooperative, uses southern Illinois coal in its coal burning plant and uses local trucking companies to transport it. This helps to boost to the southern Illinois economy by supporting mining jobs and keeping revenue in the area. Jim Riddle, CCEC's Manager, says the Centralia Correctional Facility accounts for 13.5 to 14 percent of the co-op's annual kilowatt hour sales, but accounts for only 8 percent its revenue. It's an important electric load, and it helps to stabilize rates for all the co-op's members. Bowen and Riddle agree that the relationship they have isn't your typical client/vendor relationship. Riddle's role is much more of a consultant than a regular vendor. So much at a prison involves electricity that a major outage there could be devastating. Riddle's home phone number is in Bowen's Rolodex, and Bowen doesn't hesitate to use it when it's necessary. Bowen and Riddle reminisced about a situation that could've easily gone wrong a few years ago involving Y2K. Months

of planning went into preparing for Y2K. As far as everyone knew, the prison was as ready as it ever would be, but so much was still unknown. All they could do was wait. Bowen says, "We didn't know if we'd spend days, weeks or months without power." Right before midnight on December 31, 1999, Riddle was in his office with Breese "just in case," and Bowen and his staff were in his secretary's office counting down to midnight. Bowen says that right after midnight, the room went black, and panic set in. It wasn't until the group looked around and saw lights in the rest of the prison that they realized the lights in their area had been turned off by accident. Bowen says, "We spent an immense amount of time working with the agency (IDOC) establishing contingency plans, and preparing for the roof to cave in, and nothing happened."

Riddle was instrumental in helping the prison acquire a much needed back-up power generator. It took a few years and miles of red tape to get it installed, but Riddle and the prison eventually succeeded. By having back-up power, the prison is now able to take advantage of a lower-cost, interruptible power rate. This equates to some $300,000 annually in decreased power costs. The generator also comes in handy when Clinton County Electric needs to conduct repair work on the prison's electric infrastructure. Constant communication has been the key in the successful relationship between the co-op and the prison. Finally, prisons can also be good neighbors by conducting strong rehabilitation programs for their inmates. It's commonly thought that inmates do their time and come out barely, if any, better than when they were incarcerated. The IDOC is doing what it can to reverse that sentiment. The Centralia Correctional Center, like other prisons under the IDOC, offers a strong prerelease program. This effort includes education, counseling, job skills preparation and community service work. Basically, if the inmate is qualified and willing to make the effort, he's given many opportunities to improve his life. The correctional center houses industries that provide inmates with a variety of job skills they can use when they're released. In 12 ILLINOIS COUNTRY LIVING www.aiec.org

one section of the prison, there's a flurry of activity as several inmates seated at sewing machines are stitching uniform pants. In another area of the room, an inmate is making work gloves. He proudly boasts that he turns out around nine dozen pairs of gloves per day. These products will be sold to other state agencies. The work the inmates do is carefully inspected for quality control and will be rejected if it doesn't meet standards. Some inmates are manufacturing mattresses, while others are learning trades such as construction, horticulture and food service. At least 1,500 meals are served at breakfast, lunch and dinner. The people who work in food service can receive their food service license, the same license anyone on the outside would receive. Upon their release, the licensed workers will be qualified to work at many of the largest metro hospitals and hotels in the country. The prison's garden, which is planted and maintained by inmates, helps to subsidize produce that's purchased for the kitchen. More than 100 tomato plants alone were planted this year. A large section of the garden is used to grow pumpkins that are donated to local schools during Halloween. Inmates in the horticulture program are responsible for planting and nurturing the plants and flowers that grow inside the 75-acre grounds. Inmates also contribute to the beauty outside the prison walls by helping to clean up parks, cemeteries and roadways. Another instructional area is the woodworking shop. There, a mini replica frame house is used as a model to train inmates on building walls and trusses in standard-sized houses. Cabinet-making is also taught through the program, and the fruit of its labor is evident in several areas of the prison, including the beautifully finished cabinets and shelves in the central security area and cabinets in the Warden's office. These skills are also used for community service in helping with Habitat for Humanity, a community service program that builds houses for low-income families. Educational opportunities are very important for an inmate's rehabilitation. Graduation gowns and photos of graduation classes are hung in full view at the prison, signifying the success of the prison's educational programs. Some people in the photos who are seen grinning from ear to ear are the first in their families to complete a formal education. Whether its the general education (GED) program or an associates degree program from Kaskaskia College, the certificates and degrees earned while inmates are incarcerated are identical to what students would receive in a traditional setting. Instructors from Kaskaskia College and other schools are brought to the prison to teach the inmates. The prison's classrooms look just like regular classrooms in any school. Computer training is offered on standard computers, and the prison has a comprehensive library, including an extensive law library. When inmates successfully complete an associates degree program from Kaskaskia, they participate in graduation ceremonies alongside other Kaskaskia students. Naturally, the hope is that the person who leaves the prison carries more pride and has the tools necessary to survive in the outside world. The prison system isn't perfect. When a prison closes, it leaves a major void in a community. But, it's obvious that the IDOC is doing what it can to maximize its resources and budgetary constraints. It's trying to provide the best it has to offer for its inmates, employees and communities, while maintaining as low a profile as possible. What lies behind the razor wire facade isn't necessarily what it appears to be. Positive things can grow from adversity. For more information about Illinois prisons, log on to: www.idoc. state. il.us OCTOBER 2002 ILLINOIS COUNTRY LIVING 13 |

|

|