|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

You Can Bank on Them

Bank poles, jugs and trotlines still pull plenty of weight on the water.

STORY BY JOE MCFARLAND One humid night deep in southern Illinois more than 10 years ago, catfish angler Jay Schafer pulled ashore a giant 18-pound bowfin—larger than the biggest ever recorded in Illinois—from the dark, turbid waters of the Ohio River. Schafer was fishing with primitive devices known as bank poles—rudimentary tackle consisting of a long stick, a line and a baited hook. Simple gear. It's an ancient method of fishing, widely overlooked today—yet highly effective. Two years later, Schafer broke the bowfin record again using the same technique. You've probably never noticed Jay Schafer's name in the Illinois record books because he never reported those bowfin catches to the Department of Natural Resources. Schafer isn't modest. He was embarrassed. Bowfin, also known as dogfish (grinnel in southern Illinois where Schafer lives), are considered unsavory trash fish according to many who land these long-bodied fish, only to discover they didn't catch a catfish as they'd anticipated. Despite their hefty size and thrashing, line-snapping demeanor, catching these prehistoric-era, bone-filled snakes isn't an achievement one necessarily brags about in public. "I didn't want to be known as the guy who broke the state record for grinnel," Schafer said with unhesitant disdain. So he released both bowfins, despite the fact each weighed nearly two pounds more than the current state record of 16 pounds, 6 ounces. Technically, Schafer couldn't submit those remarkable fish for state records anyway. The bank-pole devices he was using, while perfectly legal for sportfishermen, aren't recognized as tackle requiring the finesse and manipulation of casting gear. Therefore, Illinois doesn't recognize record-breaking fish caught with bank poles. Or jugs. Or trotlines. All are considered unattended devices, with any particular fish hooking itself with or without the angler nearby. To a degree, fish caught on these traditional catfishing devices get hooked by the whims of chance once the devices are set up and the angler walks away. But they work. And here's how.

September 2002 7

Jugs Why stare at a single bobber, waiting for a nibble, when you can supervise a flotilla of up to 50 chances for catfish? Jug fishing is an art of simplistic beauty. Hooks and lines beneath giant bobbers, jugs succeed through quantity. With 50 jugs floating, fish can't help but notice the bait dangling overhead, like someone bumping through a room filled with low chandeliers. Here's what to do. Start saving old plastic bottles with screw-on caps. Large jugs, such as old milk containers, aren't desirable for three reasons— they're bigger than necessary (who has enough room in the boat to haul around 50 milk jugs), the caps aren't secure (they might leak and allow the prize to sink), and big jugs drift faster than smaller ones if there's a breeze. For a quick collection, go to a recycling center and hunt for a batch. Quartsize jugs are fine. Big soda bottles (20 oz. or bigger) work nicely. To be legal, each jug must be labeled with the name and mailing address of the angler. Also, certain sites (such as Rend Lake) require jugs to be supervised by the angler, which means fishermen can't toss out a batch of jugs in the evening, head home, then return in the morning.

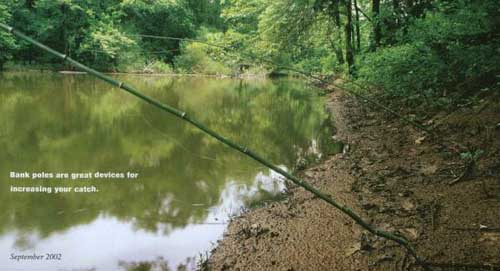

Use strong line, such as braided 50-pound test, strong enough to hold a whale. You'll need a boat to chase wandering jugs. When you spot a lively, "fish-on" jug, use a net to scoop up the jug, then grab the line to see what you've got. Bank poles Sure, they're nothing more than a springy stick with a hook and line attached. But bank poles have physics on their side—a big fish can't break one, nor can they yank it out of the mud bank. The length of bank poles easily absorbs the shock and pull of even feisty catfish, whereas shorter sticks of similar diameter would quickly snap after a fish discovers it's been hooked. To better understand the dynamics of a bank pole, think of how easy it is to snap a short twig compared with snapping a long, flexible twig. Bank poles are too springy to allow thrashing fish to get much leverage. A proper cane pole is made from exactly that—cane. In southern Illinois, where native cane (Arundinaria giganted) grows wild in bottomlands, anglers can collect enough suitable cane poles for bank fishing. A knock on a door and a handshake from the property owner are usually all that's required to cut a few cane poles. (Note: Cutting cane on state property is prohibited. When wild cane is not available, purchased bamboo poles work fine.)

Once you've collected enough poles, tie a strong, braided fishing line near the base of each pole, then tie it at 2-foot intervals, working toward the top. The series of knots along the pole helps distribute the tension while fighting the fish, just as those round guides support the line on a casting rod. Leave about as much line dangling from the rod tip as the rod is long. A 10-foot bank pole, for example, should have 10 feet of free line. Add a hook and a small weight, and you've got a basic cane pole. Sharpen the base for easier jabbing into the bank, and you're ready to go. Set the poles at a low angle toward the water (45 degrees or less—but not too low) to prevent a loss. Remember physics here. A fish will pull over a pole which is set upright, or it might slip away with a pole set horizontally. Tag each pole with your name and mailing address, even if you plan to hang around to supervise the operation. The law states that anything more than 8 OutdoorIllinois

two rods is considered an unattended device, regardless of the proximity of the angler. Trotlines Trotlines come in various forms, but all share basic properties. A strong, suspended line to which a series of baited hooks is attached constitutes a trotline (not trout line, as folks sometimes corrupt the name). Individual trotlines must not exceed 50 hooks, and hooks must be spaced at least 24 inches apart. Anglers sometimes use more than one trotline to test different waters and strategies. And that's fine. But the total number of hooks combined for all devices cannot exceed 50. (Example: Two 25-hook trotlines, which Schafer prefers, represent the maximum 50 hooks allowed.) Trotlines can be suspended in the middle of a lake or tied to shore. For shoreline-based operations, trotlines can be tied to a tree, below the water line, then suspended at some distance across the water by a buoy, which is held in place by an anchor below. Or they can be "hidden" by running the line from the bank to an underwater anchor offshore, which also reduces the risk of inattentive boaters cutting across the suspended line.

For fishing far offshore, trotlines can be suspended by buoys at both ends. It's important not to block access to bays or channels with suspended trotlines. Equally important is to tag each trotline with the angler's name and mailing address. (Conservation Police report that failure to tag trotlines, as well as not tagging jugs and bank poles, are the most common violations among those who use these devices). Tags can be simple or fancy. Anything will work, from factory-made metal tags (such as trap tags), to a piece of plastic inscribed by a permanent marker, then threaded onto the line. Management of the trotline is another art. How, exactly, does one store a long trotline with 50 hooks? The chances for tangles seem unavoidable. Almost effortlessly, it's possible to create a miserable bird's nest of Gordian knots from an improperly gathered trotline. Solution: Most trotline users gather up the main line, collecting it in a box, while hanging each hook along the rim of the box (see illustration). Ideally, the main line can be fed out into the water slowly, with the baited hooks lifted off the box rim, one by one, as the main line pulls itself out of the box. It works. September 2002 9 |

|

State Library |