|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Lincoln and Douglas as suitors By Dan Guillory

As a practical manual, The Art of Courtly Love entered the American frontier through the ecclesiastical customs, folklore, and popular novels of the day. The code of ritualized courtship was reinforced by such widely available periodicals as Godey's Lady's Book, the indispensable handbook for middle-class American women in the decades before and after the Civil War. Readers welcomed Godey's into their homes and implicitly trusted the editorial opinions on fashion, child-rearing, cuisine, popular music, and romance. Besides illustrations of trendy undergarments and flower arrangements, recipes, and practical advice on home remedies and gardening, readers could enjoy highly romanticized fiction, such as Henry G. Lee's short story, "Elopement," which titillated the audience with details of a forbidden abduction and reassuring rescue. Mary Todd was one of the thousands of ante bellum American women who favored crinolines and hooped dresses, as well as many other accoutrements from the arsenal of courtship. Mary had immigrated to Springfield from her elegant Lexington, Kentucky home to live with her sister-in-law, Mrs. Ninian W. Edwards. The Edwards home functioned as the social hub of Springfield in the late 1830s and early 1840s, and Mary, with her fashionable French from Madame Mentelle s boarding school, and her vivacious personality, quickly became the belle of the ball, ruling over an elite group of young socialites who called themselves "the Coterie" of Springfield. This Coterie included such eligible beaux as lawyer James Conkling, Democratic politician James Shields, Stephen Douglas, and a lanky, rather shy Kentuckian named Abraham Lincoln and his close friend and confidant, businessman and storekeeper Joshua Speed. In spite of Lincoln's hesitation around the ladies, the lanky backwoodsman was not unacquainted with the rituals of courtly love nor the charms of female companionship, including proper etiquette, the exchanging of gifts, and the penning of letters. From 1834 to 1836, while the young legislator divided his time between New Salem and Vandalia, he experienced the pros and cons of courtship through his association with two important women who helped to shape his later life: Ann Rutledge, daughter of a New Salem tavern keeper; and Mary Owens, also a Kentuckian and sister of Mrs. Bennett Abell of New Salem. The story of Ann Rutledge and Abraham Lincoln is fraught with controversy. The first link in the long chain of disputed evidence and dramatically varying perspectives is Lincoln's third and final law partner, William Herndon, who followed John Todd Stuart and Stephen T. Logan. In Springfield on the evening of November 16, 1866, Herndon delivered a lecture with the impossibly long title of "A. Lincoln, Miss Ann Rutledge, New Salem Pioneering, and the Poem called Immortality or 'Oh! Why Should the Spirit of Mortal be Proud'." Herndon's powerfully enunciated thesis was that Abraham and Ann were indisputably in love. Partly in deference to the tender feelings of the recently widowed Mrs. Lincoln, who could not abide the thought of another beloved in Lincoln's life, and partly because of the intervention of her firstborn, Robert Todd Lincoln, the story was officially denied and dismissed as malicious gossip or unfounded legend. Later, historians such as Benjamin P. Thomas, finding no evidence to support the Ann Rutledge story, left it to the realm of fiction. By the 1980s and 1990s, however, the advent of the New Historicism and the general cultural movement called Postmodernism had revolutionized the reading and comprehension of history. In 1990, for example, the distinguished 10 | Illinois Heritage historian John Y. Simon published his groundbreaking article, "Abraham Lincoln and Ann Rutledge," providing at least one shred of evidence: The flyleaf or Lincoln's treasured copy of Kirkham's English Grammar, inscribed with the words "Ann M. Rutledge is now learning grammar." That link is crucial because books were precious on the Illinois frontier, especially for the disadvantaged young Abe Lincoln. So the gift of the book to Ann would have been an act of signal generosity. That he and Ann were studying and writing together suggests a degree of seriousness and intimacy not heretofore appreciated. Simon then concludes with this triumphant statement:

Since 1945, labeled myth, legend, and fiction, Ann has faded into disrepute while defenders of Mary Lincoln have created an alternate legend of Lincoln's happy marriage. Ann Rutledge, however, simply will not go away. Available evidence overwhelmingly indicates that Lincoln so loved Ann that her death plunged him into severe depression. More than a century and a half after her death, when significant new evidence cannot be expected, she should take her proper place in Lincoln biography. If the Rutledge affair is controversial, Lincoln's association with Mary Owens is relatively straightforward, though his behavior toward the pudgy Kentucky maiden bordered on the outrageous. As historian David Donald tells the story, Lincoln refused to help a lady carry a rather chubby baby a lapse of good manners that infuriated Mary and he even refused to help Mary ride her horse across a deep stream. Perhaps Lincoln's oafish behavior can be esplained by his relative impovershment and his painful recognition of the difference in social and financial status between him and Miss Owens. Or, he may have developed a case of proverbial cold feet since this dilatory approach to courtship also occurs in his relationship with the "other Mary" (Todd). Nevertheless, he adopts an anti-romantic posture and deliberately turns the conventions of courtly love upside down by writing Mary Owens two inexcusably rude letters, one on May 7, 1837, and another on August 16, 1837, the latter adopting the following rather chilly rhetorical tone: I want, at this particular time, more than any thing else, to do right with you, and if I knew it would be doing right, as rather suspect it would, to let you alone, I would do it. And for the purpose of making the matter as plain as possible, I now say, that you can drop the subject, dismiss your thoughts (if you ever had any) from me forever, and leave this letter unanswered, without calling forth one accusing murmer [sic] from me. And I will even go further and say, that if it will add any thing to your comfort, or peace of mind, to do so, it is my sincere wish that you should. These are hardly the "sugared" words of an ardent lover, or the sort of "sweet nothings" designed to woo a diffident young lady. Lincoln deliberately employs an offhanded, nearly sarcastic tone because, for his own pressing reasons, he needed Mary Owens out of his life. The dismissal Mary Owens, like every other major decision in the life of Abraham Lincoln, was carefully wrought and exquisitely premeditated. Fortuitously, about two years later, in 1839, Mary Todd decided to settle permanently in the city of Springfield after a few preliminary visits, a decision that would permanently change her life and that of young lawyer Lincoln.

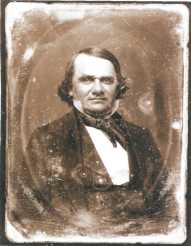

Up flew windows, out popped heads, As a part of the Coterie, Lincoln was more and more in evidence at the Edwards residence, and certainly by the latter part of 1840, he and Mary Todd were obviously in love and engaged to be married when, suddenly, the unthinkable happened. On January 1, 1841, Lincoln broke the engagement with Mary Todd, possibly for some of the same reasons that caused a similar reaction to Mary Owens, and possibly because of her flirtations with fellow Illinois legislator Edwin Webb Mary Todd Lincoln, 90. But there was a major difference in the two separations because Lincoln truly loved Mary Todd, and separating from her caused him extreme mental anguish or "hypochondria," what is now called clinical depression. Lincoln absented himself from the legislature for six working days, and his behavior generally repeated the pattern of melancholy and solipsism exhibited after the death of Ann Rutledge, as widely reported by Herndon's informants (the survivors of New Salem Village). The estranged couple carefully avoided one another, but it was obvious to their friends that llinois Heritage | 11 the spark had gone out of their lives. Mary, like most women of the day, was under intense pressure to marry, and, at twenty-three was dangerously close to the early years of spinsterhood. In Mary Todd Lincoln: Her Life and Letters, Justin and Linda Turner reprint the gossipy letters of Mary to her good friend "Merce" Levering, often on the theme of marriage. The Turners also detail the process by which Dr. Anson G. Henry and Simeon Francis, editor of the Whig Sangamo Journal arranged for the couple to meet "accidentally." The reconciliation of the couple followed soon after and the courtship ended on November 4, 1842, when Mary Todd and Abraham Lincoln were married, with virtually no advance notice to family or friends, the brides gold wedding ring engraved with the legend, "Love is Eternal."  Love and the Little Giant Stephen A. Douglas had also been one of Mary Todd's many suitors as well as a frequent dancing partner. Rumors of a proposal were in the air, and there is the famous and probably apocryphal tale of Douglas walking around the streets of Springfield with a wreath of roses on his head—all at her command. Douglas was an Easterner, a Vermont native who studied classics in upstate New York before taking river-boats west and ultimately landing in Quincy and Jacksonville around 1833. In the upwardly mobile, highly informal, rough and tumble political culture of Illinois, he quickly became a lawyer, judge, and legislator, picking up the sobriquet "Little Giant" along the way. He was already well known by the time Mary encountered him in the parlor of Ninian Edwards. Though Lincoln and Douglas shared a similar taste in women, they are, in almost every other respect, a study in contrasts. Mary summed the differences up by saying that Douglas was "a very little giant" while Lincoln remained her "tall Kentuckian. Physical height aside, Douglas made the overall neater appearance, especially by the time of the 1858 debates with his fine trousers and silk cravats he even had his own train and cannon to haul and announce him as he went from town to town in Illinois. Unlike Lincoln, who shunned alcohol and tobacco, Douglas moved from chewing tobacco to cigars, and from frontier corn liquor to imported brandy, cognac, and champagne. And their voices were at opposite ends of the spectrum, too, with Douglas deep booming tones contrasting with Lincoln's higher-pitched sound. Lincoln occasionally lapsed into frontier pronunciations like "whar" for where, "hearn" for heard, "cheer" for chair, and "kase" for because tendencies still evident by the time of his Cooper Union speech. These vestiges of the backwoods humanized and branded Lincoln, in spite of his sartorial improvements evident in the Mathew Brady portrait and his outstanding command of rhetorical structure and powerful illustrations during the speech itself. Douglas, by contrast, performed his speeches with much gesturing, sweating, theatrical stares, long pauses, and animated movement about the stage or podium, with thumbs hooked in suspenders and eyes bulging from their sockets. Lincoln often appeared awkward or uncertain about how to position his lengthy arms or massive hands. Their differences as political orators and formulators of legal and constitutional positions are reflected in their courting styles, which account for their unconscious reflexes on stage and their most telling contacts with their audiences. Lincoln was rarely, if ever, shaken, or reduced to vulgarity and ad hominem arguments as in the famous exchange between Douglas and Salmon P. Chase over the Kansas-Nebraska bill on January 30, 1854. Lincoln's occasional jokes and "down home" manner often worked to soothe and win a crowd, even if the style exhibited fewer pyrotechnics. As in his courting, Lincoln was deliberate and balanced, aiming for the classic ideal of the via media. Douglas, on the other hand, was born-a quick study, a master of the performing Self. Audiences remembered his speeches more as theatrical events, whereas Lincoln s words were driven home like square nails in oaken planks.  ouglas was usually far too busy being a "man's man," drinking whiskey at political rallies and chewing tobacco, as well as performing countless chores for the state and national Democratic party, to find much time for the niceties of courtship and wooing. But during the winter of 1844-1845, he was briefly caught up in the swirling social life of Washington and was observed "flirting with the ladies," like Phoebe Gardiner (cousin to Pres. Tyler's wife) and the vivacious Mary Corse. He certainly desired female companionship in a permanent way, and his devotion to politics also provided him with matrimonial opportunities, first in the person of Martha Martin from North Carolina, who was twenty-two years old when Douglas married her in 1847, but, unfortunately Martha died some six years later in 1853. In 1856 Douglas remarried, taking as his bride twenty-year-old Adele Cutts from Maryland. Like Lincoln, he tended to choose ladies who derived from genteel Southern families, and like Lincoln, who was criticized for having a Southern wife, especially during the Civil War, Douglas was attacked, sometimes savagely, for his first wife's ouglas was usually far too busy being a "man's man," drinking whiskey at political rallies and chewing tobacco, as well as performing countless chores for the state and national Democratic party, to find much time for the niceties of courtship and wooing. But during the winter of 1844-1845, he was briefly caught up in the swirling social life of Washington and was observed "flirting with the ladies," like Phoebe Gardiner (cousin to Pres. Tyler's wife) and the vivacious Mary Corse. He certainly desired female companionship in a permanent way, and his devotion to politics also provided him with matrimonial opportunities, first in the person of Martha Martin from North Carolina, who was twenty-two years old when Douglas married her in 1847, but, unfortunately Martha died some six years later in 1853. In 1856 Douglas remarried, taking as his bride twenty-year-old Adele Cutts from Maryland. Like Lincoln, he tended to choose ladies who derived from genteel Southern families, and like Lincoln, who was criticized for having a Southern wife, especially during the Civil War, Douglas was attacked, sometimes savagely, for his first wife's

12 | Illinois Heritage connections with slavery and for his second's wife's religion, Roman Catholicism, a tempting target for the "American," Nativist, or Know Nothing Party. Like Lincoln, he was a devoted family man, and he involved Adele in his political campaigns, a move as progressive as his "canvassing" or campaigning directly to the people. And his first wife, Martha, softened and civilized Douglas, curing him of some of his frontier roughness, including, as Johannsen lists them, these domestic vices: "profanity and coarse language, a taste for good American whiskey, [and] the disgusting habit of chewing tobacco." All the diffidence and carefulness exhibited in Lincolns courting of the two Marys isn't visible in Douglas courtship of Martha and Adele and that same pattern obtains in a general way in their writing and speaking.

Douglas was by all accounts a brilliant extemporaneous speaker who could marshal facts, dates, and details in a most impressive manner, speaking for as long as two or more hours at a time. But it is hard to think of a single memorable line that he uttered, even though many of those words changed the course of American social history and geography. Lincoln, on the other hand, gave posterity page after page of words and phrases that have become signatures of American culture, including the House Divided Speech, the Farewell Address, the Gettysburg Address, and the Second Inaugural Address. Douglas convinced his audiences by force of his logic and his well-disciplined army of facts. He liked to do historical research on his topics, and he was "severely logical" in his presentation, while Lincoln exhibited, in his finest moments, a grace, brevity, and originality of phrasing that put him on a level with Shakespeare and other masters of the English tongue.  he ultimate impact of Douglas and Lincoln's speechifying as courtship may be their undeniable effect on posterity. Lincoln and Douglas changed the national discourse by giving us both an enabling language and a sense of empowerment to change the direction of our lives, to readjust our moral compass, and to set spinning the precious gyroscope that keeps us balanced and alive as a nation and as individuals. In the end, their appeals, although radically different in style, were not altogether different in effect. They are forever linked, the alpha and omega of ante bellum American culture; had they not lived and interacted, we would inhabit today a far different and much diminished American landscape. he ultimate impact of Douglas and Lincoln's speechifying as courtship may be their undeniable effect on posterity. Lincoln and Douglas changed the national discourse by giving us both an enabling language and a sense of empowerment to change the direction of our lives, to readjust our moral compass, and to set spinning the precious gyroscope that keeps us balanced and alive as a nation and as individuals. In the end, their appeals, although radically different in style, were not altogether different in effect. They are forever linked, the alpha and omega of ante bellum American culture; had they not lived and interacted, we would inhabit today a far different and much diminished American landscape.

Dan Guillory is Hardy Professor and Chair of the Department of English at Millikin University in Decatur. He is the author of several boolzs, both prose and poetry, and is completing a book entitled The Lincoln Poems. This article was talien from a paper he presented at the 2003 Illinois History Symposium. To request an e-copy, write ishseditor@eosinc.com. Further reading Baker, Jean. Mary Todd Lincoln: A Biography. New York: Norton, 1987. ______. "Mary Todd Lincoln: Managing Home, Husband, and Children." Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association. 11 (1990): 1-12. Douglas, Stephen A. Kansas-Lecompton Convention. Washington, D.C.: L. Tower, 1857. Capellanus, Andreas. The Art of Courtly Love. Trans. John Parry. New York: Norton, 1969. Capers, Gerald M. Stephen A. Douglas: Defender of the Union. Boston: Little, Brown, 1959. DeRougemont, Denis. Love in the Western World. Trans. Montgomery Belgion. New York: Pantheon, 1957. Finley Ruth. The Lady of Godey's: Sara Josepha Hale. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1931. Johannsen, Robert W. Stephen A. Douglas. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997. Lee, Henry G. "Elopement." Godey's Ladys Book. 41 (Jan. 1850): 91-93. Lincoln, Abraham. Speeches and Writings, 1832-1858. Ed. Don E. Fehrenbacher. New York: Library of America, 1989. ______. Speeches and Writings, 1859-1865. Ed. Don E. Fehrenbacher. New York: Library of America, 1989. Masters, Edgar Lee. Spoon River Anthology. 1915. New York: Collier, 1962. Randall, Ruth P. The Courtship of Mr. Lincoln. Boston: Little, Brown, 1957. Simon, John Y. "Abraham Lincoln and Ann Rutledge." Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association. 11 (1990): 13-33. Thomas, Benjamin P. Abraham Lincoln: A Biography. New York: Knopf, 1952. Turner, Justin and Linda Turner. Mary Todd Lincoln: Her Life and Letters. New York: Knopf, 1972. Walsh, John E. When the Shadows Rise: Abraham Lincoln and the Ann Rutledge Legend. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993. Wilson, Douglas. Honor's Voice: The Transformation of Abraham Lincoln. New York, 1998. Illinois Heritage | 13 |

|

|