|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

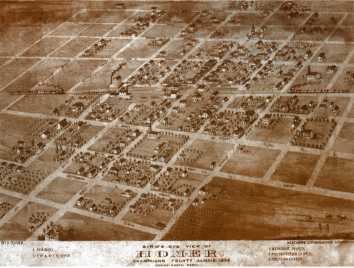

Virtue and Vice in Homer: The battle for morals in a central Illinois town, 1870-1890 By Ray Cunningham

The liquor issue The origins of the split over the liquor and moral issues went back to the days of Old Homer and the founding of the Methodist Episcopal church. Homer was a frontier town on the western edge of civilization in 1830s to 1840s. Town founders were individualists not used to the conformity of social organizations. Liquor was freely available on the Salt Fork. Sellers such as Reverend "Billy" used the bottle to spread their particular brand of Christianity from the back of an ox. Traveling Methodist pastor Rev. Arthur Bradshaw found Old Homer a place of sin when he arrived in 1839, discovering that dances were being held and liquor sold. As Randolph Wright noted in 1902, Rev. Bradshaw "[O]ften declared that on that occasion he captured one of the devil's outposts and by the help of God had upturned the thrones and principalities of hell, where "wickedness had previously reigned supreme." The battle over the sale of liquor in Homer began in 1850 with the founding of the Sons of Temperance, an organization advocating total abstinence from liquor. The group built a hall in the small village on the Salt Fork. Their effort mirrored a growing national movement against alcohol, primarily based in religious circles. The group gathered such stalwart Homer citizens as Justice of the Peace James Wright, merchant Michael D. Coffeen, and physician Dr. James Core. In 1855, four years after the village moved south to the prairie to meet the Great Western Railroad expansion, editors of the Central Illinois Gazette of Urbana observed that Homer, while "being a little cold" in recent years, found the temperance movement heating up. "We hope that during the coming winter our friends will be active in their efforts to thoroughly exclude every symptom of the presence of the liquor traffic." By 1870, Homer was the pre-eminent agricultural town in Champaign County. The end of the Civil War brought a measure of growth to the small community with a population increase of 69 percent from 1860 to 1870. New immigrants from the east, some from England and Ireland, moved to the region, while Civil War veterans returned to establish businesses and families. Homer attracted people from Ohio, Kentucky, and other Illinois towns who sought new opportunities in the rich agricultural farmland and developing business community. The population was predominantly Protestant and Methodist. The largest church in Homer was the Methodist Episcopal Church, which preached a decidedly temperance message. The Presbyterian Church did not strictly adhere to temperance, but the smaller Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) did. Merchants and enterprising individuals knew that profits from the liquor trade could be lucrative. As communities in central Illinois matured, their leaders confronted the social issues raised by the sale of intoxicating beverages. On Main Street Homer, intoxicated men wandered the streets in the evening, causing fights and generally making an evening stroll on the boarded sidewalks unpleasant. Fair weather likewise brought out the drunks. Homer's liquor was supplied from Danville by rail. "How long, oh Lord! How long will this smuggling business be carried on?" railed a Champaign County Gazette reporter in 1872. The first crackdown came on October 6, 1873, with the arrest of Jacob Day and Martin C. Frary. The $100 fine imposed by Justice E. C. Haines in Homer was for selling intoxicating liquor. The Homer jurors knew the reputation of the men and wisely requested a change of venue. Day's case was probably prejudiced by his conviction a week earlier in an Urbana court for selling liquor. 14| Illinois Heritage The village trustees decided in May 1874 to charge $500 for a liquor license. Saloonkeeper Pat Carey was granted a license, as the Danville Weekly News noted, "to ruin the young men of Homer." The Homer village board was ambivalent about the sale of liquor. Income from such licenses could be great, amounting to a good part of the village budget. But there were ramifications, including occasional evening brawls on Main Street. Those causing most of the problems were sons of the town founders. The second generation of Homerans, the sons and daughters of the pioneers, were making their mark on the farms and village, but many lacked their parents' spirit of self-sufficiency and found comfortable village life preferable to shaping the prairie. William Coffeen, son of pioneer Michael D. Coffeen, was a frequent participant in the "Main Street Jubilee," as the brawls were called. He chose to pay his fines and get back to the party the following week. The Homer correspondent of the Danville Commercial pleaded, "Where are our town authorities that they will tolerate such conduct and take no action in the matter? Echo answers where." One curious feature of the time was the feud between Homer and Sidney over liquor. While Homer allowed liquor sales in the early 1870s, neighboring Sidney did not. Sidney's citizens seeking liquor would make the journey to Homer to purchase alcohol. When Homer was dry in the mid 1870s and Sidney was selling again, Homer's newspaper editors would rail against Sidney, proclaiming victory against liquor and condemning Sidney. One Sidney citizen took exception and reminded readers of the Champaign County Gazette, "Homer should not crow over Sidney after sending us rot-gut for several years when we had no license."

In the village election of April 1877, Homer held a vote on the sale of liquor. The anti-liquor group prevailed by 22 votes in the village and 44 votes in the township. Temperance supporters celebrated the evening of the election. Homer was dry once again. But not for long. Soon the community fell back into the familiar pattern of the early 1870s, with citizens illegally smuggling liquor to the village. The fall of 1877 brought intense activity against bootlegging. Red ribbons, worn by abstainers, were frequently seen on Main Street. The M. E. ministers fervently preached on temperance; itinerant guest speakers and occasional street orators likewise lectured on the evils of alcohol. Nevertheless, several sons of the pioneers of eastern Champaign County actively procured liquor and sold it from their places of business. The center of activity for the liquor trade was the blacksmith shop of James William Umbanhower. Jim "Bill" was the son of Homer pioneer blacksmith James Umbanhower. Jim Bill was known to go to Danville, filling his earthenware crocks with grog and returning with them on the train for resale. An editorial in the weekly Champaign County Gazette protested the "gallon store," as it was known in Homer, and incited the citizens to act: With such agitation from the pulpit, from the street, from temperance meetings, and from the press, it was inevitable that someone would act. On December 21, 1877, Umbanhower was returning with his crocks from Danville when he was met by a mob near the depot. Armed with clubs, they broke up his crocks and then went after the blacksmith. But the mob was not finished. The following night the mob returned with bats and bricks and went after Umbanhower's shop, destroying his business. Vigilantism continued in Homer that winter and wasn't limited to bootleggers. When Thomas McKee's Bank of Homer failed on January 14, 1878, McKee's barn burned at 2 a.m. that evening. Homer's problems with liquor did not end with Umbanhower's banishment. A drinking shanty still existed in the village and drunks were reported to hang out there in January 1878. A call for action on the part of the temperance movement was requested. On Monday, January 23rd, a Illinois Heritage | 15 drunken fight between William Coffeen and Juke Morris occurred on Main Street. Several others joined in, ripping Morris' clothes off. "The first mentioned [Morris] appeared on the street in a state similar to Adam's first appearance before he had eaten the forbidden fruit," the newspaper reported, "and the second mentioned was not much better." No arrests were made, however, further infuriating the righteous citizens. Coffeen's problems with the law continued. The following month he was involved in a Main Street fight with Frank Canaday and Tom Donnelly. This time the law intervened and Coffeen left town to pay for his misdeeds. Canaday paid for the pane of glass he broke in the fighting. Successful events in Homer in the 1870s were judged by how many intoxicated citizens were seen. That year the largest annual event, the Fourth of July, was guarded by the red ribbon squad and drunks were kept away. The tragic death of Tom Donnelly in 1882 was a warning to all who imbibed heavily. Donnelly was working on the Sherfy farm, south of Homer. After being paid, he headed for Danville for a drink. Returning home he was "thoroughly imbibed with the ardent spirit" and took the wrong train to Tilton, where he attempted to board a freight train and was run over by a switching engine. He lived twenty minutes after the accident. He left a wife and three children.

1883 saw new challenges to Homers temperance laws. The issue of "hard" versus "sweet" cider was fought in the courts when George Veach was arrested for selling liquor disguised as sweet cider. Veach hired attorneys from Urbana and Danville to defend him, but witnesses said that two glasses of Veach's cider made them drunk. He was fined $20 and paid $33 in court costs, then had to pay his attorneys' fees. That same week, E. S. Gibson was arrested for selling a cider and pepper sauce concoction. Gibson was fined and left town. The village marshal was given instructions to arrest anyone seen intoxicated in public. Public gatherings quickly became the battleground. The largest public gathering in Homer's history occurred with the first soldiers reunion, held at the Yeazel homestead west of Homer in August 1883. Thousands descended on "Yeazel's cabbage patch," pitching tents and enjoying a carnival atmosphere. Twenty-three refreshment stands and fifteen amusement stands were constructed. But when a barrel of whisky was brought in on the first day of the reunion, deputies were quick to act. The barrel was destroyed and liquor kept out. The event was viewed as a moral success; there were no drunks and only two arrests were made. While liquor was dispatched easily, another moral problem appeared at the reunion. Arriving with the soldiers were a large number of prostitutes, allegedly from Danville, to ply their trade at the event. According to reports, twenty-four "unsavory women" were driven from the grounds, forced into the woods, and forbidden to return. Sex and promiscuity In the 1870s and 1880s, sex and morality went to war in Homer. As Homer's citizens became less tolerant of liquor, they likewise became intolerant of promiscuity and prostitution. Public condemnation of alleged moral infractions did not suddenly arise. Discussion began with the founding of a dancing club among the young people of Homer. Dancing was condemned by some religious moralists in Old Homer, and in the 1870s it was once again came under scrutiny. On October 21, 1873, the single men and women held a dance in Gilman's Hall that was initially viewed as favorable. As more dances were held, however, the events were ridiculed in the papers. At the third dance in November, one young lady sprained her ankle, which inspired the editorial comment, "she quit hopping at once." Ridicule turned into complaints when young ladies did not return home on time, or spent the night at a neighbor's house. "What makes the affair more amusing," the press reported, "is that a certain lady not long before the occasion had said that all the elite and respectability or the town attended the club dances." Outright public condemnation came in June 1877 when a young woman gave birth outside of marriage. Judgement came down heavily in the newspaper on the baby's alleged father: ...we saw this same young man out buggy-riding with a young lady of Homer on the next Wednesday. The girl who should rightly be his wife, will be obliged to cover her face through shame when in the presence of virtuous young people of Homer, who will affiliate with her betrayer as though nothing happened. The alleged father in this case made sure the correspondent published a retraction stating that he was not the father of the child. Promiscuity was the issue in 1883 with the revelation that one of Homer's young ladies was having an affair with a married man. This was revealed in a divorce suit filed in Russelsville, Indiana, by Nancy Unger, who accused her husband of having an adulterous affair with Clara Lagard of Homer. Miss Lagard had allegedly sent seductive letters to Mr. Unger. Miss Lagard worked in the Homer House hotel and had boarded for a time with the Ungers in Indiana. She had sent money to Unger to lure him away from his wife. The newspaper's righteous wrath fell on Mr. Unger who, it was predicted, "would find Homer too warm for his health." Mr. Unger apparently was no prince; it was reported later that he had twice previously seduced "frail damsels" in Homer. Homer was occasionally visited by traveling bands of prostitutes. In the early 1870s, groups of "soiled doves" Illinois Heritage | 17 caravanned from rural town to rural town, slipping away with their ill-gotten gains before law enforcement could catch them. In June 1887, two traveling prostitutes from Danville were fined $3 apiece, and the men arrested for soliciting them were given notice to leave town. Only gambling was exempt in Homer's battle between vice and morality. Before 1889, gambling in Homer was confined to card games, traveling scams, and betting on elections. Newspapers did not record any controversy about gambling until 1897. Gambling at the soldier's reunions, in the form of carnival games, was tolerated. At the Homer Fair in 1889, a track specifically for horseracing and gambling was constructed; it quickly became institutionalized. Sunday closing - Breaking the Sabbath The church's view was clear: A moral community did not conduct business on Sunday. In Homer, businesses were closed on Sunday and a village ordinance provided for a $3 fine, but there is no record that anyone ever was prosecuted for breaking the Sabbath. The issue was dormant until the moral awakening in the late 1870s. In 1877, Homer's "Sabbath breakers" were chastised in the Danville Commercial newspaper. One local man who went from the village to the country to buy feed was warned: "Our advice to him is to do his hauling on week days or he may get himself into trouble which will be somewhat expensive. A word to the wise is sufficient." But as Homer's business community developed, more businesses began to ignore the ordinance. Like the liquor issue, a backlash against Sabbath-breaking simmered until 1889. As business expanded and merchants prospered, their influence on village trustees grew. If churches weren't vigilant, merchants in Homer would soon be doing business on Sunday. The Christian Church particularly frowned on Sunday opening and waged a campaign against the practice. On July 28, 1889, ministers and parishioners from the three local churches met at the Methodist church to discuss a Sunday closing ordinance. Although a law had been on the books for many years, it had been ignored. Michael D. Coffeen Jr., nephew of the deceased pioneer merchant and a prominent member of the Christian church, presided over the meeting, where a resolution was passed to "lend our aid and support to the ministers of this place in their united efforts to bring about a better observance of the Lord's day. Mayor A. C. Woody was absent from the next village trustee meeting, which gave ordinance supporters the opportunity to act. In August, trustees resurrected the old ordinance, which leveled fines for Sunday opening and authorized the village marshal to enforce the law. Cash registers were silent on the second Sunday of August 1889, but merchants surreptitiously conducted business from their back doors. The marshal warned this would not be tolerated. But once broken, the Sabbath could not be contained; merchants and citizens alike disobeyed the law. By October, the village again amended the ordinance to exclude charitable events, barbershops, drug stores, hotels, and livery stables. Ice delivery was permitted; loafers, however, were not allowed on business premises. Soon, Homer was open on Sunday, again over the objections of some citizens. The issue reappeared in the village election of 1890, resulting in a compromise: Sabbath closing would be enforced "except in case of necessity or for charitable purposes or when the party shall conscientiously observe some other day of the week as Sabbath. The battle ended with the merchants opening on Sunday and fines ignored. The struggle for the morality in Homer did not end in 1890. While the two decades of the 1870s and 80s were the most active, the following century would see alcohol and sexual issues played out at Homer Park, and the village would again alternate between wet and dry. Today the village is dry, in part because of the struggle waged over 120 years ago. Ray Cunningham is manager of records services at the University of Illinois Foundation. He is currently writing a history of Homer, due for publication in 2005, the community's sesquicentennial. This article originally appeared in the Champaign County History Quarterly, published by the Champaign County Historical Museum. 18 | llinois Heritage |

|

|