|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

By Christopher J. Young

While the winter chill still held Chicago in its grip, long-time White Sox fan and season ticket holder, Dan Ferone, informed Chicago White Sox management that he had decided to cancel his season tickets. Soon afterwards, Michael Veeck, Promotions Director of the Chicago White Sox and son of club owner Bill Veeck, wrote to Ferone trying to entice him to come back. He explained that management had tried "to make Comiskey Park more than a baseball stadium with an infield and an outfield. We have tried to make the Chicago White Sox more than a baseball team with uniforms, bats, and balls." It was their goal, Veeck told Ferone, "to give Chicago baseball fans more than nine innings of a baseball game." In fact, their "game plan" was to make a Sox game "fun, exciting, and memorable." In short, they hoped "to give our customers the best entertainment in town for their money." During the 1979 season Mike Veeck proved as good as his word. Comiskey Park became ground zero for Veeck-led promotions. One such promotion was Disco Demolition Night, which took place on July 12, 1979. The idea was to attract people to the ball park by giving them a discount at the gate. Admission was 98 cents for anyone who brought a disco record to the park. This was on top of another promotion that was going on that night—teen night—which allowed teens in for half price regardless of whether or not they had a record. The result was hugely successful in terms of numbers. Comiskey Park was filled beyond capacity. Some estimates

On the other hand, the promotion was a failure. While the park was packed—every owner's dream—the field itself was deemed unplayable in the aftermath of the promotion, which took place between games of a twilight double-header between the White Sox and the Detroit Tigers. As a result, the White Sox organization in general had to accept a forfeit, while Bill Veeck in particular had to endure a barrage of criticism from the press. Disco Demolition Night was not just about a cultural battle between disco and rock 'n' roll; it was also about a clash between the subcultures of athletic and music entertainment. When we take this perspective the stories of owner, Bill Veeck, and fan, Dan Ferone, are heard and become part of the story—as they should since they, the baseball fans, were the ones who lost out that evening. By the time disco was all the rage in the United States, especially after the 1977 hit movie, Saturday Night Fever, it had already been part of Europe in the discotheques for some time. While everyone was getting in on the disco phenomenon—from the Rolling Stones to Sesame Street— critics, such as Steve Dahl of WLUP in Chicago, gathered militant followers dedicated to anti-disco. Newspaper reporter Toni Ginnetti described Dahl as a "24-year-old self-avowed crusader against disco music." The militia that he led in his crusade to "annihilate the forces of 6 |ILLINOIS HERITAGE disco: was called the "Insane Coho Lips." Critics of disco have tended to focus on the mechanical nature of disco. Many would have agreed with a writer for Time who characterized the disco sound as a "diabolical thump-and-shriek." However, while the musical aspect of disco no doubt disturbed Dahl, when asked he tended to focus on disco as a cultural force. "The disco culture represents the surreal, insidious, weird oppression because you have to look good, you know, tuck your shirt in, perfect this, perfect that." "It is all real intimidating. Besides the heavy sociological significance," he continued, "it is just fun to be a pain in the ass to a bunch of creeps." Although Disco Demolition Night was not the first time he led his army into cultural battle, it would prove to be the most notorious.

While the forces of anti-disco gathered, Michael Veeck looked toward the 1979 season. He assured Dan Ferone that management would strive "to make sure that when you visit Comiskey Park you'll see more than a baseball game . . . [and] that when you leave at the end of nine innings of baseball, whether we won or lost you will have had fun." When Veeck's promotional acumen met with Dahl's militant anti-discoism, the result was indeed "more than a baseball game." Michael Veeck's comments to Ferone demonstrate that the son was following in the footsteps of his already legendary father, the now late Bill Veeck, who was recently labeled "the spiritual godfather of baseball promotions." Since the 1940s, Bill Veeck had made a reputation for himself by using promotions at the game to improve the pennant prospects of both minor league and major league teams. A driving point in Veeck's business philosophy was that "you can draw more people with a losing team plus bread and circuses than with a losing team and a long, still silence." Long before the promotions at Comiskey Park during the 1970s, Veeck was engaged in promoting Chicago ball clubs. In the late 1950s he owned the White Sox and helped continue the excitement started earlier in the decade. Under Veeck's ownership in 1959, the "Go Go White Sox" won their first pennant in forty years. Even earlier, in the 1930s and 1940s, Veeck worked for the North Side Cubs. He was instrumental in beautifying Wrigley Field, including the now signature ivy that laces the outfield. Even before the first game of the doubleheader began, this veteran of baseball, Bill Veeck, began to suspect that things were going to be different. Unlike other days when people made their way to the South Side ballpark, this day a lot of people were carrying a "variety of obscene signs." Veeck's suspicions were confirmed when he saw the thousands of people who were unable to get in wandering around outside of the park. Rowdy behavior that interrupted the first game of the twilight doubleheader a number of times foreshadowed what was to come. The first game had to be stopped several times because some of the attendees "began to throw records and firecrackers onto the field. . . ." This created an atmosphere that Daily Herald reporters described as "ripe for trouble." The raucous got too close for comfort for Detroit Tigers Ed Putnam. He eventually had to leave the bullpen area because of the cherry bombs being thrown onto the field. Putnam later told a reporter that a "cherry bomb landed so close to the back of my head that I could feel the explosion." A writer for the Chicago Tribune reported that players from both teams "were forced. . . to play that first game under a constant bombardment of records and firecrackers." Another baseball player experienced the rowdiness of the "fans." White Sox outfielder Rusty Torres said that he was at the receiving end of stuff throughout the first game. Some of the items thrown at him were lighters and empty liquor bottles. The native Puerto Rican joked that there "was one good bottle of rum, Puerto Rican rum." "The way things were going," he continued, "I wish whoever threw it had left a little in the bottle." Following the first game, Dahl, the master of demolition, and Lorelei, who modeled for radio station WLUP, were driven out to centerfield in a Jeep. "The Loop" disk jockey, wearing a combat helmet, then got the crowd ready for the climactic explosion of disco records. Lorelei recalled that the view from centerfield was surreal—an adjective used by many eyewitnesses. She described feeling like she was "in the middle of a beehive. All I could hear was buzzing all around me." A fan who was along the third base line recalled that the crowd was so loud that "you couldn't hear yourself think." After leading his followers in a chant of "disco sucks," Dahl, as promised, blew up the disco records, which was meant to be a "symbolic cooling down of disco fever." Whether that was the result of disco remained to be seen, but it didn't cool down Dahl's anti-disco followers. In the wake of the explosion 5,000-7,000 people stormed the field. Not since 1925 had Comiskey Park experienced such a scene. Commander Dahl tried to rein in his troops, but to no avail. Bill Veeck stood at home plate and hopelessly pleaded with the crowd to return to their seats. In another attempt to get the people off the field, Harry Carey sang "Take me out to the ball game." Normally at a ball game Carey's rendition would bring a crowd to its feet in a happy sing along of the classic song, but this was not a normal situation, and this was not his normal audience. The baseball legend and the legendary song fell on deaf ears as the disco haters set a bonfire in the outfield, tore up the playing field, stole bases, and destroyed a batter's cage. Finally, the Chicago Police in riot gear appeared. When the activity began to dissipate, close to 40 people were arrested. Surprisingly, only one person ILLINOIS HERITAGE| 7 was injured, which actually was unrelated to the melee. Chicago Police Lieutenant Robert Reilly remarked that that evening at Comiskey Park was "as bad as the night the Beatles were here." While the buzz in the ballpark intensified and then finally broke loose with the storming of the field, baseball fans tried to flee a scene that looked to be quickly descending into a riot. Dan Ferone described the scene as one of "panic and fear. Records were being thrown from the bleachers like frisbees. While the teams were ushered to the clubhouse for their safety, the fans were not so lucky. One fan remembered that between "the games when the nonsense started, a record album hit a buddy, Ron Battaglin, right between the eyes, vertically. Blood everywhere. Beer everywhere, too. He toughed it out with the help of the nectar of the gods." When sixteen-year-old Brian Pegg settled into what he thought were great seats—roughly 20 seats from the field along the third base line, between the dugout and the bullpen—he didn't realize that his memories of the evening wouldn't be from the ball game. Instead he remembered that firecrackers and records were being thrown down from the upper deck. One M-80 blew up just above the head of an elderly man, and a 45 rpm record lodged itself in a woman's shoulder-blade. Anti-disco fanatics jumped turnstiles, scaled two-story fences, and climbed through the open windows of the old ballpark before the festivities began. Those who eventually wanted to leave when they felt that things were getting out of hand, or when they had heard the second game was cancelled, found it difficult to find an unlocked exit. My father, Bob Young, remembered that the only way to exit was through the main gate. So a tactic to keep thousands from entering made those who wanted to leave feel trapped. The Tribune reported that the gates were closed once 50,000 people were inside the park. Mike Veeck acknowledged that the gates had to be closed. When calculating attendance,

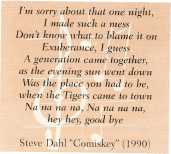

Not surprisingly, the second game was delayed. More than an hour after the second game was scheduled to start, the field was deemed unplayable. While initially it was stated that the game would be postponed, in the end, the promotion cost the White Sox and their fans a game by forfeit. In the next day's press, Bill Veeck was roundly criticized. One reporter stated that last night was "a night when Veeck's circus atmosphere came crashing down around him." An editorial in the Daily Herald commented that the "king of the promoters" and the "master showman" was "lucky that the worst that happened is that his team forfeited a game as a result." Taking a harder stand, the Tribune editors held Bill Veeck personally responsible for the "hucksterism that disgraced the sport of baseball." Veeck, according to the editorial, put the fans and players into danger by allowing for an environment that included drunken teenagers and flying records. Privately Veeck told his son, Mike, that sometimes promotions "work too well." He also told reporters that having only "one fiasco" after being in the business for four decades was "not that bad." However, he acknowledged that he had heard neither of the radio station nor of Steve Dahl before the game. For the papers the next day, he admitted that he could have done more research. Rather than pass the promotional disaster onto his son, he accepted full responsibility. Nonetheless, Mike Veeck was surprised how he had misread the situation. "I'm into music and this was my kind of concept," the younger Veeck told Tribune reporter Richard Dozer. "But the mistake I can't get over," he continued, "is that I didn't read it right." He said he could not believe how passionate people felt about the disco issue. "When I was younger," Mike Veeck explained, "I marched against the war but I never thought anyone would demonstrate for a cause like this." The responses of both Veecks illustrated the gulf between those who were at Comiskey Park on July 12 for baseball and those who were there for Disco Demolition Night. While some were there for both, accounts reveal a sharp discrepancy between the two groups. In the reporting from the time and in more recent reminiscences, many people commented on the drug use that was going on. Moreover, others have commented on how even before they entered the park they knew this game would be different. They said that the fans going into the park were there for a rock concert rather than a ball game. While some baseball fans like Bob Young and Dan Ferone opted to leave the park, others let out their frustrations on the anti-disco fanatics. Phil Allen, a Steve Dahl fan, but present that evening as a Sox fan, said that where he and his brothers were sitting the fans were singing "Na Na Na Na, Na Na Na Na, hey a**holes, sit down." Another person said that in "the upper deck we were throwing beer on the jerks, to no avail. . . ." A number of those interviewed commented on the differences between the fans there to demolish disco and those who were there for a ball game. The Tribune said that Disco Demolition Night—and all that came with it—had "little to do with why baseball fans come to Comiskey or any other park and even less to do with the game of baseball." While amazed by what had happened, and while the target of the Chicago 8 |ILLINOIS HERITAGE Tribune editorial, Veeck would have concurred with the editors. Like them, he believed that those involved in the mayhem were not "real baseball fans." So many people showed up at the ballpark that evening for their 98 cents admission that eventually ticket holders were not even admitted into the park. Some of those ticket holders that were admitted were not pleased with what they experienced. Terry McArdle told reporters that he had gone to Comiskey Park to see a game. "It was really sad," he said, "that most of the people out there had no consideration for the sports fans." Announcer Harry Carey believed he understood the reason. He reportedly said that "the people that caused the trouble were not typical baseball fans."

The front page of the "Sports/ Business' section of the Tribune on the morning after Disco Demolition Night is revealing. There are two headlines. One announces, "When fans wanted to rock, baseball stopped." The other declares, "Sox promotion ends in a mob scene." Together—the section title and the two headlines—get at the crux of the matter. No one would deny that major league baseball is business. And the White Sox of the 1970s were owned by one of the shrewdest businessmen in baseball. However, when the business of sports brings two subcultures together in one venue, the end result is ultimately going to be unsatisfying for one side. The Veecks had hoped to bring people to the ballpark, whether it was a season ticketholder or the person who likes to take in an occasional game. Judging by the number of people inside the ballpark, Disco Demolition Night, as a promotion, was extremely successful—it filled the ballpark beyond capacity. Paradoxically, however, it was also a failure. The promotion brought together at Comiskey Park people who arrived for different reasons. While rock fans and baseball fans appreciate the memory of the evening, the fact remains that in terms of baseball some ticketholders were never allowed into the park, and those that were in the park lost out on a second game. Disco Demolition Night demonstrated the limits of promotions for sporting events. In this case it crossed the promotional threshold for a sporting event because it attracted rock fans—not baseball fans—to a baseball game. David Israel of the Chicago Tribune said the following day that he was not surprised by what had happened. "It would have happened any place 50,000 teenagers got together on a sultry summer night with beer and reefer." Nonetheless, Israel commented, "It was a nuisance. And it really had no place at a ballpark." Israel's sentiment was echoed by many in the aftermath. Even so, promotions remain a regular feature of minor and major league baseball. Having said that, then, perhaps White Sox pitcher and Texan Richard Wortham's assertion after Disco Demolition Night can be tested: "This wouldn't have happened if they had country and western night." Christopher J. Young is an assistant professor of history at MacMurray College in Jacksonville. He dedicates this article to his grandfather, Henry Young (1894-1954) and to his father, Bob Young. He gives special thanks to his uncle, Dan Ferone.

ILLINOIS HERITAGE| 9 |

|

|