| by Robert D. Sampson

Historical Research and Narrative

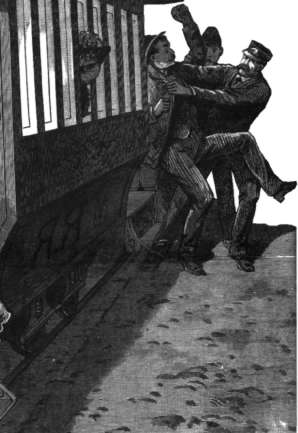

Swinging an iron bar in a wide arc before him, Wabash Railroad detective William Ballard attempted to clear away the human mass surrounding a locomotive engine on July 1,1894, in the railway's congested Decatur yards. His curses rose above the chugging of the steam engine and the shouts of the crowd as people gave way before him. Suddenly, a man jumped out from the crowd and pointed a gun at Ballard, but as the railroad detective reached for his own weapon, some in the crowd pulled the assailant's arm down and dragged him away. Cool heads and timely action had averted bloodshed. Significantly, it was the actions of the striking railroad workers and their supporters-not the Wabash Railroad employees-that had prevented bloodshed. The Pullman Strike, which began in Chicago in late June 1894 and quickly spread throughout the country, was a collision between two worlds—workers who wanted some measure of control over their economic lives and corporate managers unwilling to cede that control. The Pullman Strike is, perhaps, the most studied of all United States strikes. It was a turning point in the relationship between workers and employers and set a tone that would prevail-with a few exceptions-until the mass unionization campaigns of the 1930s and 1940s.

|

|

The Pullman Strike brought the fledgling American Railway Union and its leaders, including Eugene V. Debs, into a confrontation that would end in the union's destruction-but not before the workers nearly brought the combined railroad companies to their knees. And while most articles and studies on the strike focus on its point of origin, Chicago, the story of the strike in Decatur provides vivid examples of how it affected the lives of workers and their community. By 1894 Decatur was on its way to becoming the industrial/manufacturing city it would remain for much of the twentieth century. The 1890 United States Census found Decatur with nearly 17,000 residents, up nearly 6,000 from the 1880 figure. In pre-automobile America, railroads were the lifelines of transportation, communications, and economic development. Decatur's rise had been assured in 1854 when the north-south Illinois Central Railroad and the east-west Great Western Railroad crossed in the Macon County seat. By 1894 five railroads came through the city. The Wabash-the Great Western's successor-was the largest of the five. It had two separate lines entering and leaving the city, and its role as a prime switching point on the line created jobs for shop men who kept its engines and cars repaired, switching crews who put together trains of passenger and freight cars, and running crews who manned those trains.

The Wabash made a lot of money through its Decatur operations. Its passenger depot there sold more tickets than its other depots, including those in Chicago and St. Louis. Any interruption of service in Decatur would have a major impact on the railroad's operations and revenues. With a $2 million investment and a payroll of about $50,000 for 700 Decatur workers employed at Decatur, the Wabash made a significant economic impact on the city in the late-nineteenth century. Jobs like many of those offered by the Wabash in Decatur were good ones by late-nineteenth-century standards, with wages that allowed workers to own |

|

23

their homes and provide their children with opportunity. Putting such jobs in jeopardy was not a step to be taken lightly. And workers in Decatur, throughout the rest of Illinois, and the nation had reason to fear for their jobs. By the summer of 1894, the United States was in the second year of its worst depression to date. The Panic of 1893 had left 16 percent of the Illinois labor force out of a job, and a national coal strike lost in the spring by the fledgling United Mine Workers increased unemployment in communities, including Decatur, which had coal mines. Unions, by and large, tended to be organized around skilled workers after the failure in the 1880s of the Knights of Labor organization to represent all workers. This was particularly true in railroads where the "Brotherhoods," unions that represented, respectively, engineers, firemen, and conductors, ruled and were frequently played off against each other by railroad managers to break strikes.

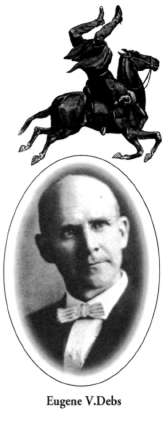

Eugene V. Debs, a charismatic figure from Terre Haute, Indiana, once embraced this view of organizing and rose to leadership in the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen. However, as the rapid pace of industrialization continued and railroads and other corporations increasingly consolidated, Debs came to believe that the growing impersonality of the system made the Brotherhoods approach outdated. By the early 1890s, he had formed the American Railway Union (ARU), based on the principle that it would organize and represent all workers in the industry regardless of skills or job titles. The solidarity Debs hoped to build would perhaps serve as a counterweight to the tremendous political and financial power of railroad corporations.

| Almost immediately Debs's organization gained an impressive victory in a strike against the Great Northern Railroad, and railroad workers around the nation began flocking to its standard. In June 1894, when the ARU gathered for its national convention in Chicago, the delegates were flushed with success. The convention agreed to hear the pleas of a delegation of workers from Pullman, Illinois, a company town owned and operated by George Pullman, the inventor and manufacturer of the sleeping cars used by all the rail lines. Pullman had cut the wages of his employees in reaction to the depression while not lowering the rents he charged them for their homes in his town. When a delegation of his workers attempted to meet with him to discuss this and other grievances, Pullman fired the men. Conditions quickly deteriorated, and the workers and their

24

families suffered from lack of food as they went on strike. The ARU delegates were deeply moved by the pleas of the Pullman workers and-over Debs's opposition-voted to order all ARU members to refuse to handle any trains containing Pullman cars. Rightly as it turned out, Debs felt that the ARU still lacked the strength to take on the combined might of the railroads but sent word to local ARU unions to institute the boycott. The boycott began June 26 and within days involved more than 124,000 workers. Of the five railroads serving Decatur, the Wabash had the most dissatisfied employees. Like the Pullman workers, the Wabash men had endured salary reductions and layoffs. The Brotherhoods had done little or nothing to prevent these actions, leading to discontent among their members. Additionally, Decatur's railroad workers, like others in the industry, saw themselves as middle-class citizens with a stake in the community. Many owned homes, and the jobs they labored in carried a measure of respect and envy. Many felt that the actions of the Wabash managers were undermining their financial status. Quietly in the days immediately following the June 26 boycott, Wabash workers made plans to stand up for their rights. On Saturday, June 30, a number of them gathered in Engineers Hall, a meeting place located only a few blocks from Union Depot, the center of railroad activity in the city and the point where the Wabash and Illinois Central lines crossed.

|

From the meeting emerged a determination to not only support the Pullman workers by boycotting trains containing Pullman cars but to also strike in their own interests. Engineers, especially, were unhappy with the railroad's wages, but it was the switchmen, men who primarily worked in the yards putting together trains, who first walked off the job. Engineers and firemen followed them, and by 7 p.m. that day the Wabash yard had, according to a local newspaper, the appearance of "a deserted race track." The cooperative efforts of the various Wabash workers crossed skill lines and gave birth to the Decatur local of the ARU, which would use Engineers Hall as its headquarters and rallying point throughout the strike.

Significantly, at the June 30 meeting, the men also agreed that "an act of violence was the enemy of the strikers" and followed through on that pledge by ensuring that no violent acts were authored by striking Wabash employees. This commitment was demonstrated when the armed man who confronted railroad detective

Ballard was restrained. Unlike Chicago, Spring Valley, and the Vermilion County village of Grape Creek-all places where violent confrontations led to loss of life—Decatur's workers held to their standard of conduct as "honest men and law-abiding citizens."

|

As Wabash trains pulled into Decatur, crew after crew shut their locomotives down and walked away. Passenger trains were stranded. With Decatur shut down, the Wabash faced a huge barrier to the flow of traffic on its system given the city's key role in switching trains and soon was losing an estimated $40,000 per day in revenue. In the early hours of July 1, as trains continued to come into Decatur and be abandoned by their crews, three railroad officials sat atop a pile of ties in the yards and contemplated what they could do to get the trains moving again. Perhaps it was coincidence or perhaps it was orchestrated, but a few hours later a telegram addressed to Governor John Peter Altgeld from "500 Sufferers" arrived in Springfield, calling upon Altgeld to send troops to Decatur to get the trains moving again.

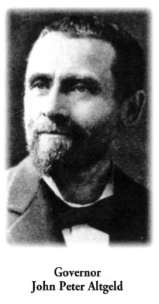

In 1892 Altgeld became the first Democrat elected governor of Illinois since the 1850s, benefiting from a Democratic sweep that sent his fellow Democrat Grover Cleveland to a second term in the White House and elected countless other local and state officials of their party. John Keiser, a historian who has written about Illinois during this time, believes the votes of workers were "instrumental" in the Democrats' sweep of Illinois. Altgeld cemented his relationship with workers and antagonized powerful business interests when, after only a few months in office, he pardoned the surviving three men charged with conspiracy in the 1886 Haymarket bombing in Chicago. In doing so, Altgeld issued a scathing indictment of the judicial system that had falsely imprisoned them and executed four of their fellow defendants. The governor was painfully aware, too, that employers sometimes called for state troops not so much to ensure order but to break strikes. He had even issued an order prohibiting the use of state troops for such activities. Yet, Altgeld would send troops to Decatur, troops that helped break the strike. Why? |

|

| As governor, Altgeld took very seriously the charge to preserve public order. He preferred that local officials first exhaust all means at their disposal to do so, but when convinced they had done so, he complied with requests for the National Guard. Altgeld had good reason to suspect that the chief local law enforcement officer in Decatur - Macon County Sheriff |

25

Peter Perl, could not preserve order. Only a year before with a mob gathering outside the jail, Perl had taken a train to Chicago to visit the World's Fair. The mob broke into the jail that evening and dragged an African-American accused of rape from his cell and lynched him from a light pole across the street from the jail. Altgeld was outraged by this atrocity and issued a fiery message denouncing it and its perpetrators, none of who were ever charged or brought to trial. Aware of Perl's incompetence, Altgeld mobilized a Decatur unit for duty at Union Depot and the Wabash yards and prepared to send more troops to relieve them. Perl, however, saw a greater duty due to the Wabash than his helpless prisoner of the year before and spent most of the strike in the railroad yards, assisting in the switching and movement of trains.

A tremendous outpouring of public support, however, complicated movement of the trains. Thousands of people descended upon Union Depot and the immediate vicinity, some of them no doubt attracted by curiosity but many in support of the strikers. It was estimated that as many as 5,000 people were gathered along the Wabash tracks from Union Depot to the end of the yards several blocks to the east.

|

The mood was festive, and a local newspaper said the throng gave the rail yards the "appearance of a parade ground." Many cizitens began wearing white ribbons, the official symbol of support for the strike. Barbers in the vicinity of Union Depot refused to shave the strikebreakers and special deputies imported by the Wabash. Waitresses at nearby hotels and lunch counters refused to serve such men. Prominent local citizens spoke up for the striking men, and the pastor of the First Methodist Church, one of the city's largest, defended the strikers from his pulpit. Even inside the Wabash's Decatur headquarters, the railroad's managers could not control opinion. Addie L. Davis, a widow who was stenographer to one of the Wabash's local executives, expressed sympathy for the strikers, remarks that touched off an argument with her boss and Davis's departure from service to the Wabash. Given such sentiments and the peaceful conduct of the strikers, it is no wonder that one local newspaper termed Altgeld's dispatch of troops to the city a "thunderclap from a clear sky."

Not every citizen supported the striking men, and among the opponents were some of the city's most influential citizens. When rumors circulated that Altgeld might pull the troops out of the city, a telegram signed by local banker and land speculator James Millikin and other prominent men found its way to the governor's desk. Incensed by Altgeld's forceful public protest when President Cleveland sent federal troops into Chicago over his objection, aged veterans of the Union Army offered to assist in putting down "with relentless hands the spirit of anarchy or rebellion." The veterans called upon strike opponents to wear American flags on their lapels to counter the union's white ribbon campaign. And they praised Sheriff Perl, who was under steady rhetorical attack from the strikers and their supporters. |

|

Perl's actions led to a public and potentially costly rebuke. The sheriff had openly violated a law passed only a year before that barred the employment of non-county residents as special deputies. Perl had taken on men from Missouri and other places initially employed by the Wabash and sworn them in as deputy sheriffs. County sheriffs had to provide a bond ensuring their performance in office, and among the signers on Perl's was his fellow German immigrant Hieronymous Mueller, a gunsmith and plumber who would go on to become a leading industrialist. Outraged by Perl's action, Mueller marched down to Union Depot and, in the

26

presence of the crowd, informed Perl he was withdrawing his guarantee. Union army veterans announced they would provide "500 men" to take Mueller's place.

While between them-the state troops, the railroad's detectives and strikebreakers, and Perl-they were able to restore some movement to the Wabash's Decatur operation, it was actions far away from the city that doomed the strikers' cause. President Cleveland's Attorney General Richard Olney was a former attorney for railroad interests. He appointed as special district attorney in Chicago a man who was the lawyer for the Railroad Managers' Association and then authorized him to seek a sweeping federal injunction that would not only break the strike but also send Debs and others to jail. The injunction was granted in Chicago on July 3 and was in force nationwide. Two days later, placards posted around Union Depot announced that even attempting to talk to strikebreakers was a violation of the injunction and would result in arrest. In Chicago, Debs's communications with ARU locals were hamstrung by the injunction. The Decatur strikers complied with the judicial order and kept up their efforts to maintain morale and non-violence through day-long meetings in Engineers Hall. However, as the trains began moving and the striking workers and their supporters were effectively shackled, it became increasingly clear that the strike was lost. Faced with a loss of their jobs, and perhaps their homes, some men began contemplating a return to work.

|

Around midnight on July 11, seven strikers applied for their old jobs and within a few hours, a dozen followed their lead. By the next morning, men were flocking to the railroad's Decatur headquarters, seeking to return to work. It was then they learned that not only would Ballard, whose aggressive conduct had irritated many in the community, play a major role in determining who would be re-hired, but that he also had planted spies in the ARU's ranks and could produce transcripts of remarks made by individuals during meetings in Engineers Hall. For its part, the Wabash was apparently determined to make things as difficult for the strikers as possible so as to discourage future job actions. Now local supporters were called upon once more. This time, rather than wearing white ribbons or supporting the strikers, they were asked to sign petitions of individual men trying to regain their jobs. At the Wabash shops, 140 of the 200 men who went on strike were re-hired. The remaining 60 were fired. Attrition was heavy among the trackmen and switchmen who worked in the switching yards, with many being told they were "out for good" as far as the Wabash was concerned. Tom Burke, a painter in the Wabash shops, was one of those "particularly marked for decapitation," in the words of a local newspaper. He was a leader in the ARU local and said he had no regrets about either his course of action or what now faced him. "I went in with my eyes open and knew just what to expect if we lost. It was either win or lose and I'm ready to take my medicine. My only regret is that I'll probably have to leave Decatur. I have come to like the town as a place to live." Burke left Decatur, bound for Cincinnati, the newspaper reported, hoping to find work. In the collision of the world of workers and the world of corporate interests, Burke and thousands of others had lost. But rather than give up, they moved ahead and rebuilt their lives.

The Pullman Strike is rightly considered a major watershed in U.S. labor relations. It clearly demonstrated that solidarity, nonviolence, even a just cause were no match for the combined power of national corporations and the federal government. It would be four decades before the labor movement would try again to transcend organization around skills, this time succeeding through the Congress of Industrial Organizations and its successful organizing campaigns in the automobile, steel, and rubber industries. The experience of Decatur in the Pullman Strike demonstrates many things, including the centrality of railroads to economic development, the decisive power of institutions and forces outside a community to determine that community's present and future, and, though it failed in the end, the power of non-violent solidarity to effectively challenge impersonal, distant corporations. |

|

27

|

CURRICULUM MATERIALS

Malcolm W. Moore, Jr.

Overview Main Ideas

One of the most widely studied of all strikes in the United States, the Pullman Strike is covered in virtually all United States history books and taught to virtually all students of United States history. Because George Pullman's railroad cars traveled throughout the United States, the strike affected more than just Chicago. While supporting the Pullman strikers, Decatur workers went on strike against the Wabash Railroad for many of the same reasons as the Pullman workers in Chicago.

Connection with the Curriculum

This lesson begins by making sure students have some basic knowledge of what a strike is. It asks students to identify the basic players and issues involved in the Decatur strike as well as looking at the other stakeholders-members of the community who took sides. Then students are encouraged to compare the events in Decatur with events in Chicago, drawing some generalizations as to why the strikes failed. They will write a piece of performance art with a partner to explain and debate the positions of the workers and the employers. Finally, the students are asked to act as arbitrators-to reach an impartial, fair settlement to these labor disputes. The lesson may be appropriate for the following Illinois Learning Standards for language arts and social science: 1.C.3c; 1.C.3d; 2.B.3a; 3.C.3a; 4.B.3a; 4.B.3b; 5.C.3b; 14.D.3; 15.A.3b; 15A3d; 15.E.3b; 16.C.3c; 16.D.3; 18.B.3a.

Teaching Level

Grades 9-12

Grades 7-8, for some lesson activities with modification

Materials for Each Student

• A copy of the narrative portion of the article

• A copy of each activity and handout

Objectives for Each Student

• Read and retrieve specific information from the narrative and other sources

• Examine the varying viewpoints of individuals and groups with regard to the Chicago Pullman strike and the Decatur strike of 1894

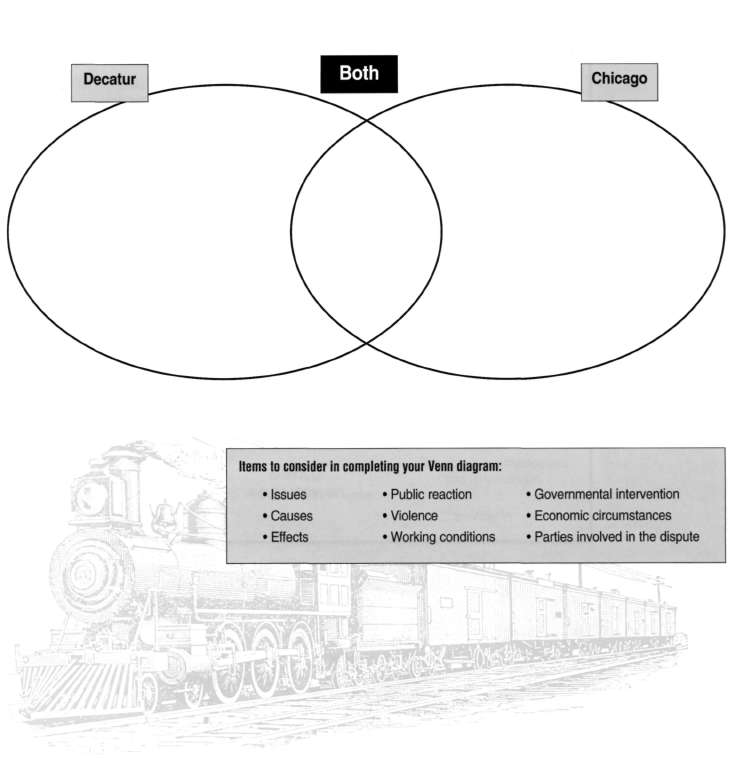

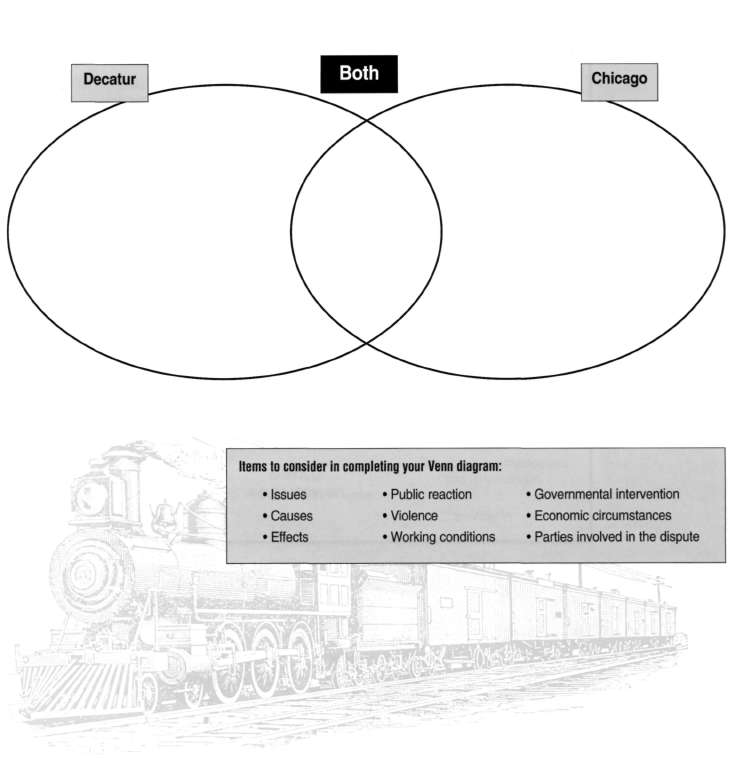

• Collect and analyze data using a Venn diagram

• Collaborate with a partner and in a group

• Synthesize information from the narrative and other sources into original written expression

• Draw conclusions based on evidence

• Orally present work to class

• Listen attentively and respectfully as others present work to class

|

|

SUGGESTIONS FOR TEACHING THE LESSON

Opening the Lesson

Ask students what they know about strikes. As the students share, come to an understanding that a strike is an action taken by a group of workers, usually associated with a union, against an employer as a way of improving wages and working conditions. Have students discuss some strikes they know about and how they fit the class's working definition. What do they think makes a strike succeed or fail? As your discussion continues, ask students who is affected by a strike. Do they see it as just workers versus employers, or are there more people involved? It would be good to put notes of this discussion on chart paper or an overhead transparency so that the class can refer back to them as the lesson progresses.

Developing the Lesson

Once students can see that more people than just the workers and employers are affected by a strike, introduce the narrative portion of the article. To guide their reading have students complete Activity 1 as they read. This will help them to focus on the issues of the strike, to see that others are affected, and that more than just the workers and employers become involved in a strike. Use the completed Activity 1 worksheet to discuss the facts and events in the article. In closing this part of the lesson, refer back to the understandings the class came to in the "Opening the Lesson" discussion. Did this activity reinforce, change, or alter their previous understandings?

For the second portion of this lesson, students will compare the events in Decatur to the more famous events in Chicago. For this, students will need to research the Chicago Pullman strike or read an article the teacher selects for them. Depending on the abilities of the students, the resources of the school, and the time available, the teacher may wish to have students research the Chicago Pullman strike individually or in groups. Certainly there are plenty of websites with a plethora of information. With limited time, the teacher may wish

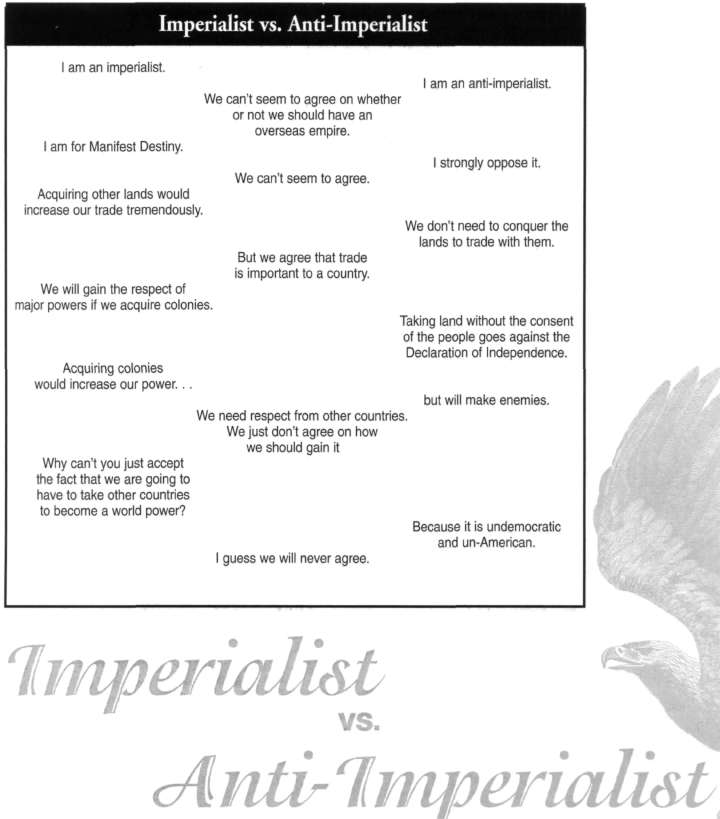

28

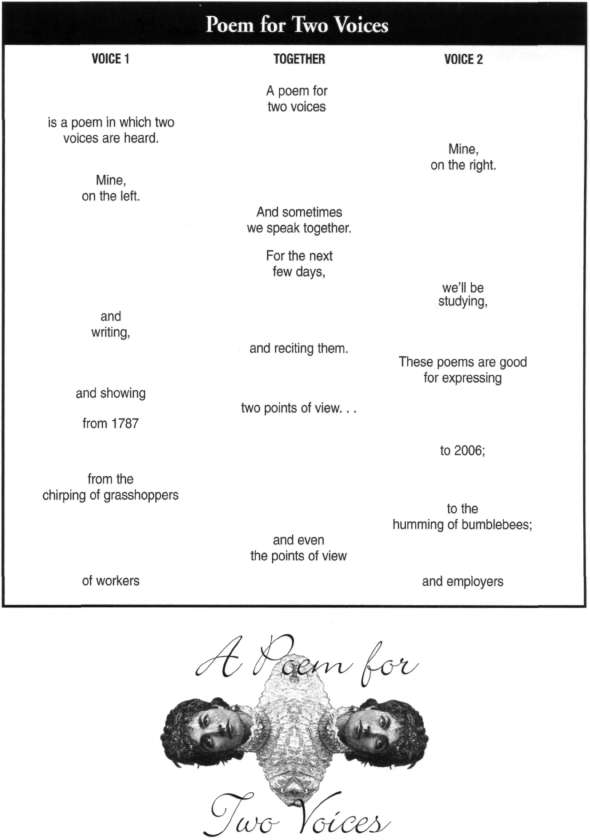

to choose one article for the entire class to use. The article, "Pullman Strike," on a website maintained by the Ohio State University, <http://1912.histoiy ohiostate.edu/pullman.htm>, may work very nicely. Once students have completed their reading and research on the Chicago Pullman strike, have them complete Activity 2, a Venn diagram that will help students to see the relationship between the events in Decatur and those in Chicago, as well as their similarities and differences. In discussing the completed Venn diagram, pose the question: "Are there clear winners and losers in these strikes?" Insist that students back up their opinions with information from the Venn diagram. Because of the nature of strikes, the differences between the sides are emphasized. Be sure to spend some time in discussion-not only on the dispute between the workers and employers but on what the two sides had in common and could agree on. Once you feel certain students are comfortable with this information, have them use it, working in pairs to complete Activity 3, a poem for two voices. A poem for two voices is an activity in which students work in pairs to analyze, synthesize, and state the arguments of two opposing sides in a controversial issue. In essence, they are creating a debate. One student speaks on one side of the debate, while the partner speaks the other side. They speak the lines of the poem that state their areas of agreement in unison. Introduce this by duplicating or making a transparency of Handout la: "Poems for two Voices: An Introduction." Have a student be one of the readers with the teacher as the other. This will act as your model and directions for students. Handout 1b: "Imperialist vs. Anti-Imperialist" is an actual example created by two eighth-grade students. This poem may be modeled in the same manner. Although it is not based on labor history, it is a fine model to guide your students when they write on labor. When the students feel comfortable with the directions and the product they are to create, they are ready to write. For this activity, students could choose either the Decatur strike or the Chicago Pullman strike. Once students have completed their poems, the pairs should perform them for each other.

| Concluding the Lesson

Before the Chicago Pullman strike began, the American Railway Union asked to have the dispute submitted to arbitration. The Pullman Company refused. Having closely examined the issues in these strikes, students will work in groups to complete Activity 4, to role-play an arbitration board to which the disputes of either the Decatur strike or the Chicago Pullman strike is submitted. It will be the job of each arbitration board to identify the issues and arrive at a fair settlement. Students need to remember that an arbitrator is a neutral third party. While arbitrators usually report their findings in writing, the teacher may choose to have students report either orally or in writing. Either way, the arbitrators' reports should include a definition of the issue(s), the evidence considered, and the final settlement. The teacher may wish to identify issues as a class and submit a single issue to each arbitration board. However, by not looking at the issues as a whole, the various arbitration boards may contradict one another. Each arbitration board should report its findings to the class.

Extending the Lesson

There are many ways to extend this lesson. Students may wish to research more about the major personalities of the Pullman Strike: Eugene Debs, George Pullman, Richard Olney, John Peter Altgeld, or Graver Cleveland. Students may wish to research other times United States presidents have intervened to halt a strike and/or order the use of troops in labor disputes. Students could create a timeline of the United States labor movement, placing the Chicago Pullman strike in the continuum of progress as workers struggled to improve their lot. Students could also explore the use of music and songs as part of the labor movement.

|

Assessing the Lesson

Much of this work will be assessed through teacher observation and class discussion. It would be helpful to have checklists to assess participation in class discussion and group work. The teacher should assess Activity 1 and Activity 2 as he/she regularly assesses class work. Activity 3 and Activity 4 are best assessed using rubrics developed by the teacher or by the teacher and students together. If the teacher is unfamiliar with developing rubrics, both Rubistar at http://rubistar.4teachers.org/index.php?screen= NewRubric&module=Rubistar are easy, teacher-friendly sites for building rubrics.

29

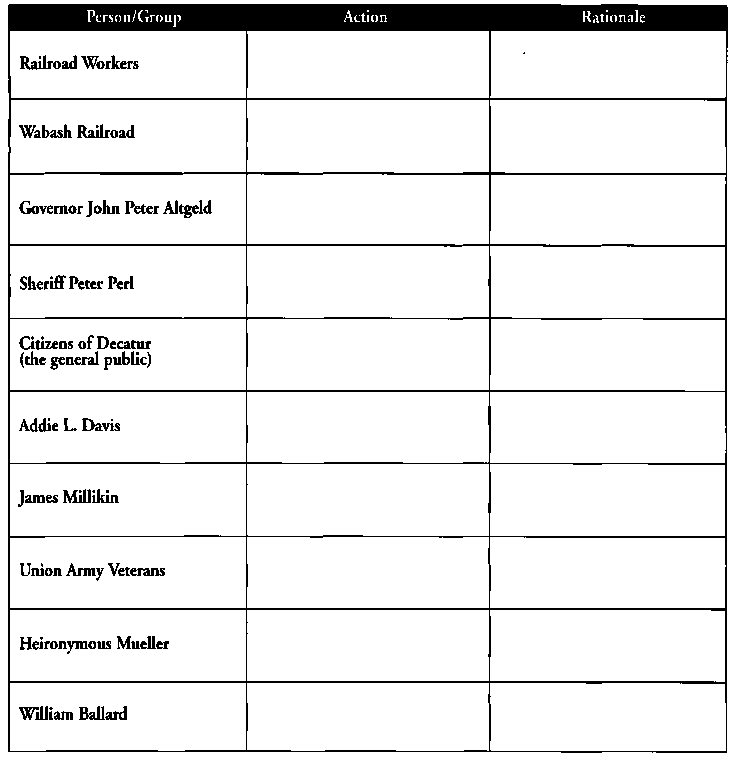

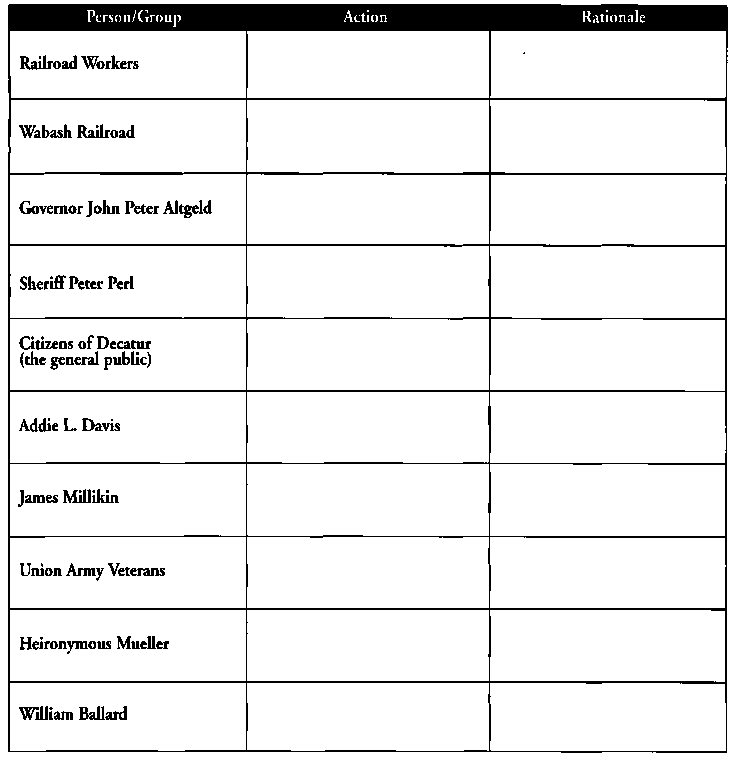

Activity 1

In 1894 railroad workers in Decatur, Illinois, went on strike to support the Pullman strikers in Chicago and, in their own interests, against the Wabash Railroad. More than just the workers and the employers became involved. As you read the article, consider each of the persons or groups listed below. In the "Action" column, write what actions the person or group took in the strike. In the "Rationale" column, write some notes explaining why they may have acted as they did.

30

Activity 2 — Contemporary Chicago!

Complete this Venn diagram to compare the Decatur strike to the Chicago Pullman Strike.

31

Handout 1A

32

Handout 1B

33

Activity 3

34

Illinois Periodicals Online (IPO) is a digital imaging project at the

Northern Illinois University Libraries funded by the Illinois State Library

|

|