|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

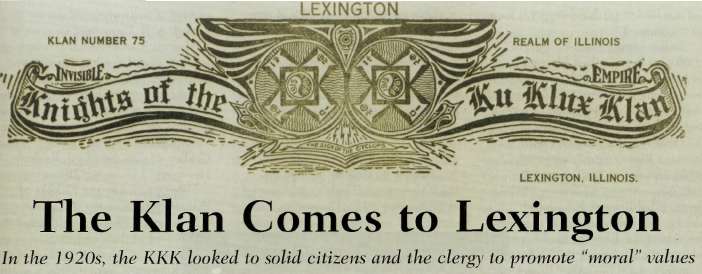

By Terri Clemens  In the summer of 1922, a Ku Klux Klan recruiter (known as a "Kleagle") came to Lexington, a small central Illinois farming community 20 miles north of Bloomington. To his surprise, the residents of Lexington greeted his recruiting efforts with open arms, and he was able to enlarge both his bank account and the coffers of the KKK. Cleaning up the town On entering a new town, the Kleagle's first duty was to meet with Protestant ministers and fraternal leaders to ascertain the concerns of the town. In 1920, Lexington was lily white, with only 20 foreign-born citizens out of a population of 1,300. The 1920s Klan was organized as a money-making scheme, and in order to induce citizens to part with ten dollars for orientation and another five dollars for a robe and hood, an issue had to be found that had relevance in each community. On reviewing the Klan's menu of issues with Lexington leaders, it was found that the best fit was promoting Protestant moral values. This included Protestant Bible instruction in the schools, disdain for the Pope, and generally "cleaning up the town." In central Illinois, most towns participated in the Klan based on the need for Prohibition enforcement or because they felt threatened by the growing Catholic population. African-American and Jewish populations were small and did not pose a threat to the status quo. Racism was so prevalent that it was not a driving force to join a group. But Protestants were becoming a minority in the United States. A national uproar against the new Catholic immigrants from Eastern Europe included rumors that the Pope, who many considered to be a foreign leader, planned to take over the country in an armed revolution manned by the Knights of Columbus. Many were convinced that every time a Catholic boy was born, a gun was added to the cache in the basement of his Catholic church. The Klan took advantage of the patriotic fever drummed up during World War I by selling itself as a patriotic and religious organization. Adopting the phrase "100% Americans," used first by Theodore Roosevelt and then by the American Legion in its anti-immigrant attacks on the I.W.W. (International Workers of the World), the Klan sold itself as a Protestant, nativist fraternal group. People were threatened by the changes that came with automobiles, women's suffrage, and radio. Concern for traditional moral values made attacks on divorce, women's behavior, and wife beaters acceptable. A Lexington woman remembered, "If we had the Klan today, these kids wouldn't be running loose on the streets. Their mothers would be home taking care of them." She also remembered that the Klan was called on by local women when two "loose women" were bothering their husbands. The Klansmen obliged by catching the women, stripping them naked, and pouring road oil and the contents of a feather bed on them. A fiery summons The KKK was active around Lexington by 1922. The Protestant public was invited to hear the Illinois Grand Dragon speak on October 5 of that year. A handbill entitled "Fiery Summons" instructed Klansmen to bring their robes. Two weeks later, Lexington Klansmen attended a two-night "monster meeting" near Streator to witness the initiation of 700 new members. The event also attracted delegations from Bloomington and other central Illinois communities, such as Danvers, LeBoy, Gridley, Pontiac, and Flanagan. A sign of covert Klan activity came in January 1923, when Presbyterian minister Frank Campbell, who would soon be openly allied with the Klan, spoke to the PTA. Reverend Campbell began by explaining that although Bible study was unconstitutional in Illinois' public schools, local Protestant ministers had put together a summer Bible school and convinced the "wide awake" school board to give credit to students who attended classes in Bible Law, Bible Literature, and "How We * Lexington Ku Klux Klan letterhead courtesy McLean County Museum of History. Illinois Heritage 21 Got our Bible." Catholic students were not mentioned. In the summer of 1923, over 1,000 cars full of robed Klansmen paraded through Lexington en route to the meeting grounds west of town, where several hundred men were initiated. A week later, broadsides advertised that Rev. Ransom DeLoss Brown, a Bloomington evangelist, would expose the Klan at the city park. According to reports, 4,000 people attended Brown's hour-long address. Instead of exposing the negative side of the Klan, he spoke positively of the "doings of the KKK and what they stood for." After Brown's address, local residents learned that he had agreed to head a four-week revival at the Lexington Christian Church. At this time, Brown was still engaged in a revival in Lovington, 90 miles away in Moultrie County. During Rev. Brown's revival in Lovington, the Klan made their first public appearance there, holding a cermony in an open field outside of town. There were flaming crosses, several hundred attendees, hooded guardians at the gate, and "all that goes to make Klan sessions." It took place the night before Brown's final sermon entitled "The Truth Concerning the Klan." In anticipation of the sermon, several townspeople spent the whole day in the church, eating dinner and supper there. The crowd filled the auditorium, every available chair, and every inch of space. The service began with a quartet singing "Beautiful Robes of White," followed by a procession of robed Klansmen bearing a monetary gift. The Klansmen then knelt and Brown prayed over them before extolling the virtues of the Klan.

100 percent American Back in Lexington, Klansmen made their second public appearance in September 1923. Dressed in street clothes, 15 members traveled 8 miles to Gridley to confront a wife beater. Russell Young was an unemployed bookkeeper whose wife was a popular teacher at the high school. He had beaten her so badly that a surgeon was called, and when she returned to school the next day, she collapsed. The Klansmen found him at his parents' house and warned him to leave town and get a job. He promised to follow their orders. The same month, three robed Klansmen visited the Lexington Presbyterian Church and kneeled to pray after giving Rev. Frank Campbell a "liberal donation." That week, 3,000 people gathered west of Lexington for the initiation of more than 100 Klansmen, followed by a fireworks display. The Knights of Pythias, another fraternal organization, announced that "near 40 K of Ps joined the Ku Klux Klan last Tuesday night," and that a large crowd of brothers attended a KKK meeting the next night in Chenoa to hear a speech. Rev. Brown opened his four-week revival at Lexington's Christian Church in October 1923. Some of his subjects were "The Fiery Cross," "Why I Am 100% Christian," and "Americanism." Robed Klansmen donated flowers and money during the Fiery Cross sermon, and also presented red and white roses to all men for their mothers on "Mother's Night." A flurry of Klan activity occurred during the revival. A. R. Carnahan, soon to be Lexington Klan's Exalted Cyclops (or leader), began to advertise his new auto repair shop as the "100% American Repair Shop." A big meeting and initiation were held at Van Dolah's pasture, and Lexingtonians attended initiation meetings in nearby Chenoa, Gridley, Colfax, Stanford, Fairbury, Heyworth, LeRoy, and Bloomington. By November, the Knights of Pythias column in the local Lexington Unit Journal newspaper estimated that 80 percent of their members were also Klansmen, and that 60 percent of the local Klansmen were members of the Knights of Pythias. This meant that the Lexington Klan could claim from 250 to 400 members. The Unit Journal also listed Klansmen, complete with advertising for some of their businesses. [Mayor] Knight T.M. Patton Esquire John Laird advertises Klean Klassic Kooking at his restaurant. Knight C.R. Swartz Kant Keep Kandy. He sells it while fresh. Knight Robert Carnahan has a shop to Klean Karboned Kars. Knight Ray Arnold shaves you with Klean Klear Kold water. [Tire Vulcanizer] Knight WE. Hanback is Kleaning and Kutting Ka sings. Knight Ed Goforth does Klean Kut Klassic shoe repairing. Knight Henry Grubb says Pete Kant Kwite Kut threads on gas pipes. [Constable] J.B. Klawson was seen driving down the streets of Kexington last Saturday in his Klattering Kerosene Kar ringing a Klining, Klattering. Klammering bell. The involvement of Lexington churches in promoting Klan ideals continued in December. The Christian Church announced a sermon on "American Education: Patriotism and Religion Must Go Hand in Hand for a Successful Nation." A converted Jew, David Bronstine from the Jewish Presbyterian Church of New York, 29 Illinois Heritage lectured at the Presbyterian Church. The Knights of Pythias rang in the New Year: Meanwhile, Rev. Brown left Lexington to lead a revival in nearby LeRoy. Box ads in the LeRoy Journal advertised Klan public meetings in the high school auditorium and the city park, featuring Kleagle Finley Callahan of Bloomington, who would be explaining the Klan's principles. The "Klan Bowl"

Rev. Finley A. Callahan hailed from Indianapolis. In 1923, he was the proprietor of the Interdenominational Holiness Mission, whose offices were in Bloomington. In March 1924 Callahan, accompanied by two truckloads of children and six carloads of adult Christian workers, held a street meeting in Lexington where they sang old gospel songs. Callahan also "touched on the subject of the KKK of which he is a strong member." Lexington kluxers dedicated their "Klan bowl," a wooded pasture on the Van Dolah property just west of the town, in July 1924. The bowl included a high spot where townspeople could see the flaming crosses. A thousand central Illinois Klansmen were in attendance for a fireworks display and the initiation of eighteen men. The Knights of Pythias reported that several brothers traveled 100 miles to Springfield to take the second degree of the KKK, while the K of P Drum Corps practiced for a September Klan parade in Bloomington. That summer, the Popejoy School near Lexington was the target of Klan political activity. Most of the children served in this rural district were Catholics of two extended families large enough to control the school's board of directors. Voting together, these families took turns hiring teachers from their own families. In 1924, the election of a Catholic director was contested by the Protestant challenger, who lost by one vote. She was able to have the election overturned because some ballots were not initialed by election judges. A "valid" outcome was achieved after four ballots, and Daisy DeVore won the directorship. On the first day of school, Josephine Killian and Helen Swartz, both of whom had signed contracts to teach that year, reported to the school. The next day, Ms. Killian was accompanied by her father, who had hired her before the election was overturned. Mrs. Devore had him arrested and charged with disturbing the school. Mr. Killian was found not guilty, but the Protestant teacher, soon to marry Klansman Mayor Tilden Patton, taught the school for two years. Bigger better bass The Lexington Klan held a Gala Day on October 14, 1924. There was "something doing from noon until midnight." The Grand Dragon and Grand Titan, the state's and province's top officers, were among the speakers at the day-long meeting. Twelve thousand people were welcomed with a parade featuring several handsome floats, robed and-hooded horses and horsemen, the Odd Fellows band from Pontiac, and four drum corps, including a Klanswomen's Corps from Watseka. With 900 robed Klansmen and women, Bloomington received the $25 prize for the largest delegation in the parade. Mayor Patton celebrated the Popejoy School victory by driving a float bearing a large picture of a schoolhouse labeled "District #210." Patton didn't wear his mask because everyone in town knew he was in the Klan. The meeting ended with a $600 display of fireworks, enjoyed by spectators for miles around. Delegations from Watseka, Clinton, Decatur, Quincy, Springfield, Bloomington, Peoria, and Pekin participated in the festivities. During the weeks of preparation for the big meeting, the Knights of Pythias announced that the KKK held a special meeting in the K of P lodge room with 200 or more in attendance. Knight Robert Carnahan attended the National KKK Klonvocation in Kansas City. The Knights of Pythias bragged: "We wonder why the K of P all like Lexington so much. Lexington is known the state over for K of Ps and KKKs." Lexington's Catholic citizens were offended, but not intimidated by the Klan. After a big Klan meeting, William Kauth, a German Catholic, cut the guide wires that held the gigantic wooden cross in Van Dolahs Illinois Heritage 23 pasture, toppling it. When a KKK banner was hung across Main Street in front of his blacksmith shop, he responded by painting "B.B.B." in four-foot letters on his building. Klansmen speculated on the meaning of the letters. One townsman remembered that the letters stood for "Bad, Buzzards, Bastards." Kauth told his family members and a young Catholic friend, though, that the letters meant "Bigger Better Bass,'' referring to Kauth's reputation as a topnoteh fisherman and maker of fishing lures. Joseph Killian, a high school student, was scolded by school officials when he refused to buy a yearbook because it contained an ad from Klansman Ray Arnold using a KKK alliteration. His daughter remembered that his feelings had been hurt by the prejudice of many townspeople, creating a schism that took years to heal. The Klan disrobes The excitement over the Klan quieted in 1925. The Knights of Pythias column in the local newspaper no longer mentioned them. Yet there were still public activities. For example, the Lexington chapter (or "klavern") gave stained glass windows with patriotic and religious themes to each of Lexington's Protestant churches and presented Bibles to the school. In November 1925, the Klan hosted a meeting at the city park with a concert by a 35-piece band, a male quartet, and a speaker from Texas. By 1926, Popejoy School again had a Catholic teacher. During the two-year term of the Klan-backed Protestant teacher, the local newspaper was without its column from the Popejoy neighborhood. The rural Catholic community had shut themselves off from their Lexington neighbors. According to Bernard Killian, who was a Catholic high school student during the Klans heyday, almost all the Protestant men in town were in the Klan. Even men who came to town to work in the fields for the summer often worked their first week to earn the $15 necessary to pay the initiation fee and buy a robe. "If a fellow didn't belong, his friends pressured him to join. It was the thing to do." Catholic families watched the parades, saw the fiery cross at the Klan grounds, and watched the fireworks, but they weren't afraid of the Klansmen. "They knew who they were and they didn't really think about them much." As national excitement surrounding the Klan turned to antipathy in the wake of Klan scandals, many decent citizens dropped from membership. By the end of 1926, one of Lexington's most enthusiastic Klansmen, Exalted Cyclops Carnahan, moved his auto repair business to the newly constructed Mini Boulevard (later Route 66), and changed its name from "100 Percent Repair Shop" to "Illini Repair." In the small towns where local matters were more important than national scandal, the Klan continued to function as a social club. In 1927, the Lexington newspaper reported no Klan activity, but a surviving twenty-five cent ticket announced that Lexington Klan No. 75 hosted an ice cream social at the Odd Fellows Hall in April, featuring Illinois Grand Dragon Gail Carter. By this time, the collapse of the Ku Klux Klan was increasingly visible. Although the national Klan announced its disbandment on February 23, 1928, a diminished Klan persevered in Lexington. In 1930, a Bloomington newspaper reported on a Klan barbeque between members of both communities. Lexington's Klan was composed of mainstream Protestants from all walks of life. Its members included the mayor, large landowners, bank directors, doctors, and businessmen, along with farm workers and laborers. It was extremely popular during 1923 and 1924, the peak years of the national Klam Its activities fit a pattern common in the Midwest. Beginning with a quiet campaign, the Klan went public when it had enough control to gain public acceptance. Enforcement of moral standards against wife-beating and promiscuity was approved by the community, although their methods were sometimes unnecessarily aggressive. Working against Catholic influence in the schools left lasting negative feelings among local Catholics. Peer pressure, excitement, and acceptance by their church and community contributed to the success of Lexington's recruitment efforts, but like most klaverns, the excitement faded when community feelings began to change. As soon as a real controversy appeared over Catholics in the schools, the weekly reports in the newspaper stopped. Within two years of its peak, the Lexington Klan was a weak and ineffectual organization. By 1944, the national organization was bankrupt. Terri Clemens is the registrar at the McLean County Museum of History. This article is taken from her master's thesis "Kluxing in Korn Kountry: The 1920s Ku Klux Klan in Central Illinois." The thesis was runner-up for the Fisher Award for Outstanding Thesis at ISU in 2005. The Klan in U.S. History Reconstruction-era Klan: Organized after the Civil War to combat carpetbaggers and newly freed slaves. 1865-1870s. 1920s Klan: 5 to 9 million members. Protestant and nativist; also trumpeted other issues. 1915-1944. Civil Rights-era Klan: Extremely racist and violent, organized to combat the movement for African American political and civil equality. 1950s-1983. Current Klans, sometimes called "skinhead" Klans: Organizationally fragmented and weak, loosely aligned with various "hate" groups. 1984 to the present. Illinois Heritage 24 |Home|

|Search|

|Back to Periodicals Available|

|Table of Contents|

|Back to Illinois Heritage 2007|

|