|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

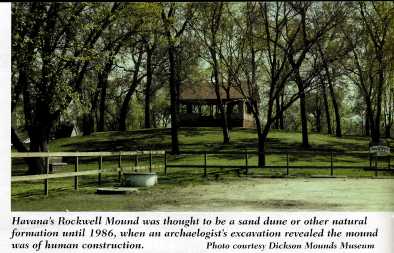

Rockwell Mound Reflecting on the past at a favorite swimming hole By Charles Hinrichs At first glance Havana's Rockwell Park, located near the Illinois riverfront, seems just another place where local children can play when they're not swimming in the community's Optimist Memorial swimming pool. Located next door to the park, the pool is the most important attraction to young Havanans during those muggy central Illinois summers.Rockwell Park has long been a part of local lore but its history dates back much further in time. N.J. Rockwell donated the ground to the community in 1849. Rockwell, one of the earliest businessmen in Havana, helped usher in Havana's incorporation in 1848. With its large hill the site was ideal for public speaking, a factor taken advantage of during the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates. Douglas spoke in Rockwell Park on August 13, 1858; Lincoln spoke there the following day. This has long been a source of the local pride, but there turned out to be much more to Rockwell Park than picnics and politics. The hill in Rockwell Park is no hill at all. It is a mound. Anyone familiar with the Illinois River Valley has heard of the mound builder people. The Dickson Mounds Museum, located just across the river from Havana near Lewistown is a famous, and at one time controversial, repository for knowledge about these ancient people. Given its proximity to a museum dedicated to this culture, it seems odd that the Rockwell Mound wasn't acknowledged until recently. Some believed it was a natural sand dune. The land formation was so much larger than other mounds in the area and wasn't the conical shape associated with the other mounds. Rockwell mound wasn't confirmed as a mound until local archaeologist Hugh McHarry received permission from the state to dig in 1986. His test trenches confirmed the mound was man-made. Based upon artifacts found within, the mound dates to around 150 AD. The people who built this mound would have been of the Middle Woodland Culture. They would have still been hunting with spear and atlatl; the bow and arrow hadn't yet entered the picture. They were known to eat the deer, waterfowl, and turkey indigenous to the area. It would have taken a skillful hunter to get close enough to take them with a spear. Michael Wiant, Director of Dickson Mounds Museum, says there is evidence that the mound people engaged in Middle Woodland funerary practices and may have had ritualized diets. They probably cultivated local plants such as goosefoot, maygrass, knotweed, barley, marsh elder, and sunflower. They would have mastered the art of pottery, he says. And evidence from other sites of this culture indicates they may have engaged in far ranging trade. But for these people to build a mound of this size would have been a tremendous undertaking. An estimated 1,760,000 baskets full of earth went into the construction of this 2-acre, 14'-high mound. Rockwell Mound is one of the best-preserved mounds in the area. Others have been destroyed by cultivation, local development, and road construction. The good news is that Rockwell Mound is in a public park and is in no danger of destruction. Archeologists can spend time on higher risk sites. Wiant suggests that the Havana sites might be the originators of the Middle Woodland culture. The Havana-Hopewell culture is found from the Illinois River Valley into the Ohio and Mississippi valleys. There may be more mounds that have gone unnoticed and will be discovered in the future. We may not know specifics about the people who built this mound for sometime. It is always necessary to balance the value of knowledge with respect for belief and the desire to preserve. In the not-too-distant future, remote imaging technology will let us study these sites without disturbing them. Until then we can only imagine the life of the mound builders from informed guesses, based on the other Middle Woodland sites. Rockwell Mound is now on the National Register of Historic Places. It sparks the imagination, and gives all Havanans a much deeper sense of community history. The pool and the great sledding may not have been the use imagined by the original mound builders, but perhaps they would appreciate that their work still holds value nearly 2000 years later. Children who swim at the base of the mound now know that other children once lived and played here, and that realization brings a new perspective to this small town in the Illinois River Valley. Former ISHS intern Charles Hinrichs grew up in Havana. He hopes to make a career in public history. 14 |

|

|