|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

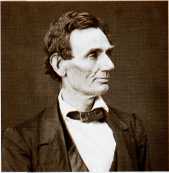

A logical alma mater Abraham Lincoln and Illinois College By Loreli Steuer (Note: The following paper was presented during the Illinois College Alumni Weekend's "Thinkin' Lincoln" festivities in June 2006.) Welcome to Beecher Hall where the first college classes in the state of Illinois were held 176 years ago beginning on January 4, 1830. Close to that time, in 1831, a young man of 22 named Abraham Lincoln arrived in New Salem, Illinois, just 30 miles away. In the next decade, Lincoln would form six close friendships with IC students and have enough direct and indirect contact with the school throughout his lifetime for a history writer named Eleanor Atkinson to refer, in the early 1900s, to Illinois College as "Lincoln's Alma Mater." Another historian, Harold E. Gibson, concurred—writing that "If Lincoln had attended any college, Illinois College would have been the most logical one." At that time, Illinois College was the only school in the state offering college level courses. Further, Gibson suggests, that had it not been for the untimely death of Ann Rutledge in the summer of 1835, it is highly probable that Lincoln would have followed her to Jacksonville, enrolling in IC at the same time she was slated to enroll in the Jacksonville Female Academy. Lincoln, then 26, had among his best New Salem friends David Rutledge, Ann's brother, who was an Illinois College student and who we know urged Ann to attend the IC women's college counterpart. It is not a large leap of logic to guess that David also urged Lincoln to attend IC—since by then, as various Rutledge family members attested, Abraham and Ann were engaged. Sadly, that summer Ann contracted what is now presumed to be typhoid fever and died. Lincoln fell into a terrible depression with friends fearing for his life. By the time he emerged from its debilitating shadows, the possibility of formally attending college was gone. However, Lincoln's contact with IC students and mentors had only just begun. IC Students in Lincoln's Life In addition to David Rutledge, whom Lincoln got to know well through frequently boarding at the Rutledge tavern, there were four other IC students with whom Lincoln was in close contact while living in New Salem. The best-known former IC student, however, Lincoln met a little later on in Springfield. Lincoln had many jobs in New Salem to earn his room and board. In his six years there, he held such varied positions as clerk, handyman, rail-splitter, surveyor, militia captain, and elected legislator. He also served for a time as New Salem's Postmaster.

Harvey Ross, an IC student, worked his way through college by carrying mail to and from New Salem. He and Lincoln enjoyed discussing the news in the papers Harvey delivered—and especially of talking politics. Another moneymaking venture of Lincoln's was buying a store with William Berry, who also attended Illinois College. Their partnership allowed them to become close friends. The store, however, was not a success and closed within a year. Berry became quite ill; some said because of his drinking, but his family members have argued strongly otherwise. However, in a College student file, there is a notation that at young Berry's graveside, his father, a Presbyterian minister known for his powerful preaching against the evils of alcohol, pronounced that his son was now "in hell." Lincoln assumed all of the store's debts after closing it, which took him years to pay off. In his words, the store "just sort of winked out." It is important to note, notwithstanding the circumstances, that no critical word from Lincoln about his IC student partner was ever recorded. Probably Lincoln's most influential and long-lasting IC student friendships while in New Salem were formed with brothers William and Lynn Greene. In particular, William befriended Lincoln soon after he arrived when they both worked as clerks in Offut's general store. William also served in the volunteer militia unit that elected Lincoln as their captain during the Black Hawk War. But the greatest act of friendship by the brothers was bringing their books and lecture notes home from IC and then tutoring Lincoln from their classes with an esteemed IC professor. When William Greene visited Lincoln thirty years later in the White House, Lincoln introduced him to Secretary of State Seward as the man who helped teach him "the only English grammar" he knew. The Greene brothers also introduced Lincoln to Richard Yates when visiting New Salem. Yates was one of the two first IC graduates and also became one of Lincoln's lifelong friends. As time went on, Yates and Lincoln became strong political allies and supporters. When Lincoln first ran for President, Carl Sandburg describes Yates as being the equivalent of "Lincoln's Campaign Manager." 16 After Lincoln won that election, Yates accompanied the Lincolns to Washington. He also became an elected leader himself, serving as Governor of Illinois and proving to be extremely helpful to Lincoln during the Civil War. Lincoln didn't meet the most famous of his Illinois College student friends, however, until after his New Salem days. William Herndon met Lincoln after Lincoln had moved to Springfield and become a lawyer and state legislator. Herndon first served as a clerk in the law office of Lincoln's second law partner, Stephen T. Logan. Later he became Lincoln's junior law partner in a practice that lasted 21 years, ending only with Lincoln's death. Herndon wrote a well-known biography of Lincoln with a famous quotation about his time at Illinois College. The year was 1837 and the Illinois College students held what might be described as the first student protest over the murder of Abolitionist Elijah Lovejoy. Herndon took part in the protest, and at that point his pro-slavery father yanked him out of IC. In Herndon's words: In the fall and winter of 1837, while I was attending college at Jacksonville, the persecution and death of Elijah Lovejoy took place. This cruel and uncalled for murder had aroused anti-slavery sentiment everywhere. It penetrated the college, and both faculty and students were loud and unrestrained in their denunciation of the crime. My father, who was thoroughly pro-slavery, in his ideas, believing the college was too strongly permeated with the virus of Abolitionism, forced me to withdraw from the institution and return home. But it was too late. My soul had absorbed too much of what my father believed was rank poison. The murder of Lovejoy filled me with, more desperation than the slave scene in New Orleans did Lincoln, for while he believed in noninterference with slavery, so long as the Constitution permitted and authorized its existence, I, although acting nominally with the Whig party up to 1853, struck out for Abolitionism, pure and simple.

Lincoln and Herndon had a most satisfactory working relationship, resembling in many instances that of a father and son: in the course of their relationship Lincoln was known to refer to Herndon as "Billy" and Herndon was known to respond with "Mr. Lincoln." Nonetheless, over its span of two decades, their great mutual respect and loyalty was never seen to waver. An inestimable influence Jonathan Baldwin Turner had a large impact on Lincoln throughout his adult life. In many ways, it is fair to say he was the first and only college professor from whom Lincoln took any classes—and those classes in grammar and rhetoric, as noted earlier, were taught by the intermediaries of the Greene brothers. A charming story about Lincoln and Turner's first direct encounter tells of Lincoln working at Turner's farm in Jacksonville one day, clearing trees and chopping wood. When Lincoln was finished, Turner came out to pay him. Lincoln then said, "I sure enjoyed your class." Turner replied, "What is your name? I don't seem to remember you." "Abraham Lincoln. I wasn't in your class, but I learned everything you taught through the Greene boys!" Thus was the beginning of a long and fruitful friendship. Turner writes of how he supported Lincoln through every election. He also had worked for many years to secure government funding so all American students would have access to a college education. He succeeded and is given credit for achieving the Land Grant Higher Education bill (called the Morrill Act for its Senate sponsor). It was the first piece of legislation that Lincoln as President signed in 1862. In the same year, Turner learned one of his sons, who was fighting for the Union, had been seriously wounded. He immediately boarded the first available train to Washington where his son was in a hospital. He stayed many weeks through his son's recovery and in that time visited with Lincoln either at his office or at his summer home on almost a daily basis—such was the strength of their friendship. Here from several of the letters written home to his wife are lines attesting to their mutual trust and admiration.

Colonel Chester In that darkest hour we were entirely willing to trust the interests of the Republic wholly in his hands. A trusted friend and president Although Edward Beecher, IC's first president, had many connections to Lincoln through his family and his close friends, Elijah and Owen Lovejoy, it was Julian Sturtevant, the second president of Illinois College, with whom Lincoln formed the greatest kinship. Each man possessed similar leadership qualities and visions of their moral obligations. Just as 17 Sturtevant, who was strongly anti-slavery in his beliefs, but saw his role as IC president to first save the College, so Lincoln similarly was strongly anti-slavery, but saw his role as the American President to first save the Union.

Evidence that others also recognized the significance of Lincoln and Sturtevant's friendship is apparent when Sturtevant was asked to be a major speaker at the Second Anniversary Memorial Service of Lincoln's death at the National Lincoln Monument in Springfield. We don't have the words he said then, but we do have Sturtevant's words written to his daughter the day he heard of Lincoln's death. It is worth reading the eloquent prose he expressed while experiencing his and his country's great sorrow over the death of their leader and friend. What a day! But yesterday we were rejoicing as no other people ever rejoiced. Today we are mourning as no other people ever mourned. This is no assassination of a usurping despot that waded to power through the blood of his countrymen, but of the truest friend of liberty that ever sat in the seat of authority. What these villains intend I know not, and care little, for they will be defeated. But what God intends concerns us more, and that I do not by any means understand.. .. All business is suspended, all places of business are deeply draped in mourning. Thousands are vowing vengeance on what remains of the rebellion, thousands more are utterly paralyzed, overwhelmed with horror and sorrow. Arrangements are made for a public meeting of citizens on Monday afternoon in view of this awful tragedy. It seems to me, if anything is wanting to fill up the measure of our hatred of the rebellion, this is it...May the Lord tranquilize our spirits and give us faith in Him in this dark hour. Honorary frat brother In January of 1859, Phi Alpha Men's Literary Society voted to make Abraham Lincoln an honorary member, as did the men of Sigma Pi a few months later. Phi Alpha had invited Lincoln to come to Jacksonville and deliver their major annual address. Lincoln agreed and gave a talk entitled: "Discoveries, Inventions, and Improvements." The event was intended as a fund-raiser for the society. For reasons unknown, the attendance was poor and the Phi Alphas didn't even raise enough money to cover Lincoln's fees. After the lecture, they told Lincoln of their dilemma. He replied that if they could pay his railroad fare and the price of his supper (50 cents), he would consider it sufficient. Celebrating a Logical Alumnus There are many more connections between Lincoln and Illinois College. Here are a few worthy of mention. Records reveal that Lincoln served as the Illinois College lawyer on at least two occasions. As a circuit rider for the county courts, Lincoln made over 40 trips to Jacksonville on legal business alone. During that time he argued 68 cases in and around the circuit court region with IC Trustee David Smith, sometimes as co-counsel, sometimes as opponents. The friendship between the two men became so close that Lincoln gave Smith his law office chair before he left for Washington. The Smith family has since generously presented the chair to the College. Another IC Trustee, Logan Hay, was the uncle of John Hay, Lincoln's assistant secretary during his first Presidential term. The Hay family also honored Illinois College by presenting two of the client office chairs from the Lincoln and Logan Law Offices in Springfield. In addition, both John Hay and John Nicolay, Lincoln's principal Presidential secretaries, recommended that IC graduate Charles Philbrick become part of the White House secretarial staff in 1864, and then succeed them as principal secretary in 1865—which he did. It would seem, as writers Atkinson and Gibson suggest, that had Abraham Lincoln attended any college, Illinois College would have been his logical alma mater. It would also seem only logical to conclude that with Lincoln's many IC student friends, that with his only college class having been "taught" by an Illinois College professor, and that with one of his most trusted friends and political advisors also having been an IC president, it is time to follow the lead of Phi Alpha and Sigma Pi literary societies in their prescient actions of some 150 years ago. Therefore, on this Alumni Weekend devoted to the theme of "Thinkin' Lincoln," I propose we declare Abraham Lincoln an honorary fellow alumnus of Illinois College and, hereafter, raise our glasses in tribute at each available opportunity. Loreli Steuer is Chair of the Underground Railroad Committee of the Morgan County Historical Society. She teaches a course entitled "Lincoln in Literature" at Illinois College, where she also performs many duties as the president's spouse. 18 Illinois Heritage |

|

|