Orndorff Award goes to Chicago student

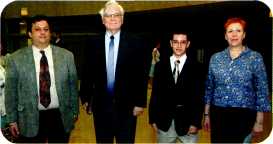

(Left to right): Josh Cohen, Chicago Metro History Center; Redd Griffin, Illinois State Historical Society; Orndorff Scholarship winner Frank Pucci; and Pauline Kochanski, Chicago Metro History Education Center.

Photo courtesy Mt. Carmel High School.

|

Frank Pucci, a recent graduate at Mt. Carmel High School in Chicago, is the 2007 recipient of the Verna Ross Orndorff Scholarship. Pucci wrote his winning essay, "Rumble in the Wigwam: The Republican National Convention of 1860 and the Story of the City that Shaped it," in the 2006 for the Chicago History Fair competition, and submitted it for consideration in the ISHS competition.

ISHS Educational Affairs Committee chair Happy Dean said the essay was "one of the best student essays I've ever read," and she complimented Pucci on his research and clear writing style.

ISHS board member Redd Griffin of Oak Park presented Pucci with his $1,000.00 cash prize at a special awards ceremony at Mt. Carmel School in May. In his remarks, Griffin said:

"Frank Pucci has shown in his essay how people, ideas and events converged to bring about Abraham

Lincoln's nomination for President at the Republican Party's national convention in Chicago. Lincoln's historic launch to the Presidency occurred in a building called the Wigwam, which once stood just over ten miles or twenty minutes northwest of here where Lake Street crosses the Chicago River....

"Frank's essay makes us aware of how what has happened close to us in time and space-in the metropolitan area we live in—can have great effects on history and the world."

The Verna Ross Orndorff Scholarship is open to Illinois high school students. Requirements include a 1,500-word essay about Abraham Lincoln or the Civil War era in Illinois. For more information, visit the Society's website at www.historyillinois.org

|

RUMBLE IN THE WIGWAM:

The Republican National Convention of 1860 and the Story of the City That Shaped It

By Frank. Pucci

Mount Carmel High School

On November 6, 1860 after much fanfare and noise, the anxious citizens of Chicago went to the polls. Chicago gave an unknown lawyer named Abraham Lincoln ten thousand votes. By midnight, the city rejoiced at hearing that their favorite son was elected as the sixteenth President of the United States. Yet, many could remember an even greater celebration one May day only a few months before. On that day, Chicago rejoiced that it had done the nation a great service in putting Abraham Lincoln on the path to the presidency. In fact, it can be said that these citizens were cheering on Election Day not just that Lincoln was president, but that they had begun the entire process of putting him there. How could this be possible? What could this city have done to shape an election? Indeed, there is a definite answer. Due to the efforts of her politicians, businessmen, and citizens, the city of Chicago was able to transform Abraham Lincoln from a trailing backwoods politician to the Republican Party candidate; trying to directly affect the outcome of the coming November election despite national obstacles. Without the city of Chicago, Abraham Lincoln might never have stood a chance of coming near the presidency. To effectively support this position, six questions need to be answered: first, what was the appeal of Abraham Lincoln to Chicago; second, how was Chicago even able to host the Republican National Convention in 1860; third, what challenges faced a Lincoln victory at the convention; fourth, how did Chicago affect the ultimate outcome of the Convention; fifth, what exactly happened at the convention; and sixth, how did Chicago really take a stand?

As with any political campaign, what first must be asked is: what is the appeal of a certain politician to a certain region? In this specific case, what was the appeal of Abraham Lincoln to Chicago? Certainly, it would seem on the surface that Chicago and Lincoln were far apart. Lincoln had very rarely visited the bustling new city before 1858. Lincoln had spent most of his time serving the citizens of southern Illinois (rural citizens), in the General Assembly. The city of Chicago was a burgeoning metropolis quickly being strengthened by its sea trade, rail industry, and both

|

14 |ILLINOIS HERITAGE

its steel and grain industry. Indeed while Chicago was striving to be a new "refined" city of the West, Lincoln would often bypass etiquette and deal with people with his commoner wit and his common sense logic; hence the ploy. Despite the idea of refinement, the working people of Chicago, those who would be rushing to the polls, loved this "western man image". When these working class Chicago citizens saw this disheveled appearance of a man, they would think, "this is no politician, this is our kind of man," and further, "Yet once he began to speak, people were captivated by his earnest and powerful delivery". This powerful display was enough to have one spectator comment that "When I came out of the hall, my face glowing with an excitement and my frame all aquiver, a friend, with his eyes aglow, asked me what I thought of Abe Lincoln, the rail-splitter. I said 'He's the greatest man since St. Paul.'" Imagine the effects of this; the vision of a small time rail splitter who had the power of the greatest orators in history. This image of the poor man's Cicero was enough to captivate thousands of Chicagoans in their support for Lincoln. Indeed, this was solidified by his depiction as the "Man of the People," essentially becoming the Republican version of the great Andrew Jackson, and looking as though he was to supplant the Northern elite. Essentially, it was to be Lincoln the Rail-splitter, the man who studied books by the fireside, the man of the "log-cabin and hard cider." However, this might have been good enough for the masses, but what of the middle and upper classes? It must be noted that while Lincoln spoke to the crowds, he was speaking to the wealthy men present. While the "Man of the People" rallied the masses, powerful men such as Norman Judd, Col. John Wentworth, mayor of Chicago, Joseph Medill, editor of the nationally known Chicago Press and Tribune, and other such men met with Lincoln, discussed his policies, and found in him the best protector of the interests of business. While Lincoln touted his humble origins, he proclaimed protective tariffs, conservative fiscal policy, railroad expansion, and political appointments to the upper crust of society. In Lincoln, many, especially among the Chicago elite, found the best champion of the suit, rather than the overalls. With these men not only would there be moral support, thousands of dollars poured into the Lincoln campaign; enough to keep him sustained to the very end of the presidential campaign. Yet, most Chicagoans found an even surer answer to support Abraham Lincoln—he was the candidate of moderation. In the negotiations for the placement of Chicago for the convention, the city was seen as a moderate ground. Here, few wished to see throngs of soldiers leave the city only to return with rivers of blood. Lincoln had time and again, in public, said that he wished that no war should be started over slavery and it should simply be limited to where it stood. The Chicago Tribune, the voice of Chicago's political and social scene reasoned that "his avoidance of the extremes" would make him the most agreeable of candidates to unite the North against all other opponents. Logically, in a city that bristled with moderacy, who better to represent its interests than the most visible moderate.

Therefore, Chicago received Lincoln with open arms. What did it matter if Chicago could not hold the convention and push her "native son" forward? This begs the question how was Chicago even able to host the Republican National Convention in 1860? On December 21, 1859, representatives of the different Republican bastions of the North met to discuss this at the Astor House, in New York. Chicago's place was precarious. At this time, many supporters of William H. Seward of New York, as well as supporters of prominent men such as Salmon Chase and Edward Bates, argued that this convention should be held in well known areas such as in New York, Ohio, or Missouri. Cities such as Buffalo, Cleveland, Cincinnati, St. Louis, and even Indianapolis were gaining ground over the head of Chicago. Now, the Illinois delegation, led by Norman Judd, stepped forward. Judd suggested that Chicago was "good neutral ground where everyone would have an even chance". Yet, the Illinois delegation, despite wanting the candidacy of Lincoln, stifled any talk of him, lest the other delegations become agitated with talk of the "rail-splitter". After many a vote, the choice was down to St. Louis and Chicago.

Again Judd, the consummate lawyer, suggested that "members of the Convention and all outsiders of the Republican faith would have a hospitable reception", and that "feeding and lodging for the large crowd would be provided....as well as a hall for deliberation". With the promise of a rather cheap convention for the Republican Party, the city of Chicago snatched the convention away from St. Louis by one vote.

At this point, Chicago had support for Abraham Lincoln, and it now had the convention. Thus, to the laymen, it would seem Lincoln should have won right away. Yet, Lincoln was not alone in his quest for the nomination. He, and especially Chicago, faced a series of opponents much more experienced and much better known that Abraham Lincoln. This begs the question of what challenges faced a Lincoln victory at the convention? The greatest of these challenges was his fellow candidates, and most of all William H. Seward. Seward, the hawk-nosed, cigar smoking, politician from New York was by far the likely nominee. Seward was an experienced politician; state senator from 1831 to 1834, governor of New York from 1839 to 1843, United States Senator from 1849 on. He was an active supporter of abolition, became a leader of the so-called Radical Republicans, and amassed a group of powerful friends and backers. To sum up what W.H. Seward offered is simple: "Seward had the money, the power, the muscle of the New York delegation; the bands, uniforms and the champagne.. .but he didn't have Chicago". Lincoln also faced other seasoned politicians; well-known former Free-Soiler turned Republican Senator and Ohio Governor Salmon P. Chase, and influential Virginia politician Edward Bates. All these men had at one time or another held high standing political offices at both the state and federal levels; all of them had friends who could easily put them in the White

|

ILLINOIS HERITAGE| 15

House. What did Lincoln have? Lincoln, at the state level, had never left the Illinois General Assembly, and had only once served Illinois at the national level (as a Whig congressman from 1846-1848). Lincoln had only the knowledge of a small-time politician, and the tactics of a trial lawyer; he could not possibly amass the experience that these men could. Another great challenge was the fact that Lincoln was an Illinois lawyer. If one was to win a nomination such as this, one would have to grab an entire region, and if Lincoln was only to win the North, he would have to win all the North. As Lincoln once remarked, "I have been sufficiently astonished at my success in the West. But I had no thought of any marked success at the East". From Lincoln's own mouth was his own doubt that he, or Chicago, could convince any delegate out of the East to vote for himself.

All signs going into the Convention pointed to an effortless Lincoln defeat. The radicals of the convention seemed to snatch any chance of a fight from Lincoln. However, in three tenuous ballots, Abraham Lincoln became the Republican nominee for the Presidency. To this end, after gaining support for Lincoln, and after grabbing the convention, Chicago would deliver the sweetest plum of all: the nomination. This presents the question of how did Chicago affect the ultimate outcome of the Convention? In order to explain this, the strategy of Chicago must be explored in

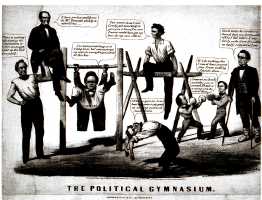

"The Political Gymnasium," political cartoon of the 1860 presidential campaign, by Courier & Ives, 1860.

From the Joseph and Lucille Block Collection, Illinois State Historical Society.

|

phases. The first phase began almost immediately after the Illinois delegates walked out of the Astor House meeting in 1859. Once again, Norman Judd would seize the initiative. Judd, a Chicago railway lawyer, persuaded the railroad companies to provide "a cheap excursion rate from all parts of the State", in order that Lincolnites from all over the state could flood the convention and the city without worry of expense or lack of funds. Next was the propaganda campaign. The only way to gain information of any kind in Chicago in the 1860s was through the newspaper. The veritable monopolizer of the news was the Chicago Press and Tribune. Abraham Lincoln knew that there was little way he could gain influence of the people by himself. Lincoln then wrote to the ever influential Norman Judd, "I am not in a position where it would hurt much for me to not be nominated on the national ticket; but I am where it would hurt some for me to not get the Illinois nomination. Can you not help me in this little matter, in your end of the vineyard?" This vineyard was the Chicago Press and Tribune in which Judd had considerable influence. From this moment on, the Tribune published constant articles on the promotion of Lincoln as the nominee. This meant that the first thing a convetion delegate would read in his morning papers is a resounding defense of Abrahan Lincoln, and a strong promotion of him. The next phase was the active participation of the populace of Chicago. For days throughout the convention, Lincoln supporters marched in the streets promoting their "Honest Abe." However, the only problem was that Seward had himself hired a group of well uniformed band paraders which provided even more stimulus to the already burgeoning candidate. However, it would be at the convention that these people would make their mark. Norman Judd and Joseph Medill, both prominent Chicagoans, were conveniently appointed to handle the seating arrangements of both the audience and the delegates. Somehow Lincoln protagonists found it easy to get tickets, but endorsers of other candidates had great difficulty in gaining entrance to the great hall of the Wigwam. On the day of the crucial day of the convention, the hall was packed wall to wall with Lincoln supporters, while the well-uniformed Sewardites stood outside with no way to influence the delegates. Now the only thing these delegates from all over the nation would see would be a hall of enthusiastic Lincoln supporters, who would not appreciate their favorite son being defeated before their eyes. The next phase was another Judd-Medill maneuver. As mentioned, these men held the crucial responsibility of seating the delegates. These two men carefully and secretly isolated the New York delegation from the delegations of those states that were doubtful of supporting Lincoln and key delegates were isolated from ardent supporters of Seward. The next phase was in the securing of the simple majority rule, which would allow Lincoln to be elected with only a simple majority of the delegates in favor, something that could be obtained. The final and most important phase was the behind the scenes politicking of go politicians and the Illinois delegates. It was well known that the key battleground states of Indiana, Illinois, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Ohio thought Seward and the other candidates too radical on slavery and too liberal on other issues to be suitable. Here the Chicagoans would strike. Behind closed doors, the Illinois delegates, backed by a committee of Chicago politicians David Davis, Leonard Swett, Norman Judd, and Stephen Logan went from delegation to delegation trying to convince them that Lincoln was the only man that could hold the nation's support. Despite the idea of using honorable means, these Chicagoans tried every measure. They spread rumors "that the Republican

|

16 |ILLINOIS HERITAGE

|

candidates for governor in Indiana, Illinois and Pennsylvania would resign if Seward were nominated". Each man was assigned to a particular state, thus a pincer movement (a tactic to split a large group into smaller pieces), could quickly cut off supporters from each state from Seward and bring them to Lincoln. First, Indiana was secured by promises of a cabinet position. Next, deals were made with the Pennsylvania and New Jersey delegations (ardent supports of Seward), that if any weakness was shown on the first ballot on the part of Seward, that Lincoln would be their choice. On and on this continued until the very last minute of the very last ballot. Three of four key states were now in Lincoln's pocket. Now it would be up to the delegates and the Chicago crowds inside the Wigwam.

With the negotiations closed, the audience secured, and with the city in formation, Chicago now watched as the convention played out. This leads to the crucial question: what exactly happened at the convention? On May 18, 1860, the delegates were called to order in the Wigwam, a two-story convention hall built at the expense of $7,000. First, the New Yorkers rose, and exclaimed their support for their native son Seward. The few supports of Seward present applauded so loudly, that an onlooker, Leonard Swett, later admitted, "it appalled us a little". Regardless, the crowd gambit that Chicago had employed now paid off. When Lincoln's name was mentioned to the crowd, their reaction was what one reporter recalled as, "like a wild colt with a bit between his teeth, the audience rose above all cry of order, and again and again the irrepressible applause broke forth and resounded far and wide". "Five thousand people at once" jumped to their feet as Leonard Swett reported. This was repeated over and over to the consternation of the delegates. At the first ballot, the tally stood Seward-1731/2, Lincoln-102, Chase-49, and Bates-48. The behind the scenes mechanisms went to work again, as more votes were garnered. The second ballot showed an astonishing Lincoln improvement; Seward-1841/2, Lincoln-181. The tight race now stood between the two leading politicians: Lincoln and Seward. The tension in the Wigwam was thick and powerful. Lincoln gradually gained votes from Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. This brought Lincoln to 231 1/2 votes, 11/2shy of victory. The tension mounted. The Wigwam was so full it was thought the walls would break. Seconds passed as if they were centuries as it came down to one man: the leader of the Ohio delegation David Kellog Cartter. Thousands of Lincolnites stood, staring at Cartter with their bright gleaming orbs, clinging onto every tense moment. Then slowly, carefully, Cartter announced a change of four votes to Mr. Abraham Lincoln. One reporter wrote. "There was a moment's silence, then there was a great noise in the Wigwam like a rush of a great wind in the van of a storm — and in another breath, the storm was here". Cannons fired; people rejoiced in the streets, the liquor ran wild. An entire city rejoiced as their favorite son, "Old Abe", their "rail-splitter", Abraham Lincoln was now the Republican nominee for President of the United States.

However, in the final analysis, what did it matter that this new city on the shores of Lake Michigan had put this frontiersman in the race for president? Ultimately, this leads to the final question: how did Chicago really take a stand? As much as it would like to be said that the city of Chicago was looking for the best man for the job, and the best man for democracy, Chicago really took a stand for its vision of reality. The elite and common people of Chicago knew one major thing: that a Republican was going to win the election, and it needed the most unifying candidate possible. In New England, many wanted an abolitionist revolutionary; in the Northeast, the machines of the major cities wanted the better established, or really, the most machine connected candidate in the White House; and everywhere else, no person really knew what he wanted in a President. Yet, Chicago had the genius of having the simplest idea: put a man in the White House who best represents all interests in moderation. In this sea of revolution, physically and metaphorically, the city of Chicago decided to stand up and stem the flood with its own solution. At the same time, the leaders of the city took a stand for perhaps a more sinister purpose; to control Lincoln. Throughout the nomination process, promises were made in terms of political appointments, infrastructure plans, and other such dealings. Through these, the most powerful Northerners would be able to achieve their own agendas through "Gorilla" Abe. Essentially, Chicago simply took the stand of reason; it may have not been as noble a cause as actively liberating a country from oppression or gaining some right, but in the end, these hard-working politicians, and these committed citizens of Chicago put a man in office who they thought could hold the Union together, which was their main stance. In the end, despite 600,000 lives lost, they were right. The loser of the convention, William Seward, put it best: "You fellows knew at Chicago what this country is facing....You knew that it will take the very best ability we can produce to pull us through. You knew that above everything else, these times demanded a statesman and you have gone and given us a rail splitter."

On that one May day in 1860, a city rejoiced in the pleasure of its accomplishment. The accomplishment can be summed up in this: had the convention been held anywhere else, Abraham Lincoln might never have been nominated as the Republican candidate for President, and in the end, might never have reached the White House. Yet, an even greater accomplishment can be seen in this event. This small, growing city of the Midwest had done the impossible: Chicago, with it politicians and people, had taken a small time lawyer and frontiersmen, pushed him from obscurity to stardom, and put him on the greatest pedestal of all: the nomination for the Presidency of the United States of America. It is not only a tale of political strategy and genius; it is a tale of great ingenuity and the will of a small city to make its presence known in a great nation. It is not just a story of a great city; it is the story of great people.

|

ILLINOIS HERITAGE| 17

|