|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

John Nerone

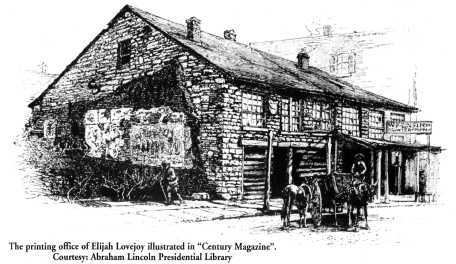

Elijah Lovejoy died defending his printing press from a mob on the night of November 7,1837, in Alton, Illinois, across the Mississippi River from St. Louis, Missouri. Lovejoy, a Presbyterian minister, edited a religious weekly, the Alton Observer. His editorials in that paper had become increasingly critical of the institution of slavery. The mob that attacked Lovejoy claimed that his views on slavery threatened to undermine the stability and prosperity of the town. The mob claimed that a local right of self-defense overrode any constitutional guarantee of freedom of expression. Unruly, violent, and illegal as it was, the mob was led and incited by local professionals and politicians, including the Illinois attorney-general. Elijah Lovejoy was born in Maine in 1802. College educated and looking for a career as a schoolteacher, he moved west to St. Louis in 1827. After he grew bored with teaching, he acquired part ownership in a newspaper, the St. Louis Times, which he edited from 1830 to 1832. Like most newspapers at the time, the Times was partisan, dedicated to the presidential ambitions of Henry Clay. Like most editors, Lovejoy slanted his news columns as well as his editorials to promote his political interests. Other newspapers in St. Louis backed other candidates, and none of them pretended to be neutral or objective. Editors and others working in the press at the time considered it dishonest and "unmanly" to hide their politics, and believed that a healthy political system needed newspapers that would energetically advocate positions, clashing with each other like lawyers clashed in a courtroom. Also, like most editors, Lovejoy made money however he could, including running ads for slave sales and runaways; at one point he hired a slave as an assistant. In 1832 Lovejoy attended a religious revival and underwent a conversion. He left St. Louis, enrolled at Princeton, and became a minister. At the end of 1833, he returned to St. Louis and began printing the Observer as a Presbyterian newspaper. Morally serious, he took notice of slavery then, and by the end of 1835 had begun to editorialize on his right to print antislavery correspondence. Missouri was a slave state on the border with a free state, Illinois, and very sensitive to antislavery activism. After an escalating series of confrontations, culminating in the destruction of his printing press, Lovejoy decided to move the paper across the Mississippi River. Slavery dominated politics in the 1830s. But the leading parties, the Democrats and the Whigs, both wanted no discussion of slavery. For both parties, mentioning slavery would mean losing votes, especially in the South; neither party thought it could win the presidency or control of the Congress if southerners thought it was "soft" on the slavery issue. Hence, both parties, but especially the Democrats, took steps to prevent antislavery activism. The parties also controlled the newspaper system. Virtually all the mainstream newspapers were headed by partisan editors who were also members of the party's local coordinating committees and often held office as well. So the nation's mainstream press supported the parties' efforts to silence antislavery activists. Editors claimed at the same time to support freedom of the press. But abolitionists, they argued, did not deserve freedom of the press, because their agitation endangered the health, safety, and prosperity of the communities they lived in. But the issue could not be suppressed. Committed abolitionists in both free and slave states formed antislavery societies and began antislavery newspapers, and some principled editors of mainstream newspapers printed 38 antislavery arguments. The parties resorted to increasingly violent means, leading to riots in Boston, New York, Cincinnati, Philadelphia, and many other places where antislavery societies or newspapers were being established. In one remarkable case, a mob led by a Democratic congressman broke up an antislavery meeting and vandalized the local newspaper office in Utica, New York, in 1835. Utica was inside the home territory of Martin Van Buren, then the vice president of the United States and hoping to be the Democratic Party's presidential candidate in 1836. Van Buren endorsed the riot and may have personally instigated it to prove to southern Democrats that he was not soft on slavery: in his personal correspondence, he remarked that "we have taken the Bull by the Horns." His scheme worked, and he was elected president the next year, the same year that Lovejoy was forced out of St. Louis.

The toxic politics of slavery followed Lovejoy to Alton. At first the town welcomed the editor and his newspaper, thinking that they would bring new respect to the growing commercial center. Because of the nature of the news system, any local publication in the early-nineteenth century would bring some national attention because news circulated through "exchanges." Newspapers got their news from other newspapers. Obviously, before the development of the telegraph in the late 1840s, there were no wire services to sell news to newspapers, and few newspapers employed large numbers of reporters or correspondents. Instead, editors clipped and copied items from the "exchanges," newspapers that other editors sent them through the postal system in exchange for a free copy of theirs. The editor of a newspaper like the Observer would build an exchange list with other papers in the state and around the country with religious newspapers exchanging with other religious newspapers, Democratic papers with other Democratic papers, and antislavery newspapers with other antislavery newspapers. Any newspaper could print an item that would be copied by other newspapers in the news system, and then perhaps recopied by yet other papers. (This system was more like today's "blogosphere" than like modern news organizations.) In a very real sense, a town's newspapers were the face that it turned to the nation. Already, because of his close brush with the mob in St. Louis, Lovejoy had acquired a national reputation in both the antislavery and religious press. Alton knew it was getting a minor celebrity.

At that point, Lovejoy was moderately anti-slavery, and had not joined those, like William Lloyd Garrison, calling for immediate abolition. Violence greeted his arrival-his printing press was seized on the dock and tossed in the river by a mob on July 24,1837—but the perpetrators were from St. Louis, not Alton. The leading citizens of Alton condemned the attack. After a few months of publication, however, his welcome wore thin. He had become a part of the network of antislavery publications and 39 gradually drifted toward immediatism. This alienated some, and they began agitating to silence him. Townsfolk claimed that he had promised not to aggressively promote antislavery. They printed handbills and called meetings, pressuring Lovejoy to stick to religious matters.

Lovejoy responded to this pressure by becoming more adamant. Arguing forcefully for his constitutional right to free expression, he insisted that he would print whatever his conscience dictated. Although his press was twice more thrown into the river—on August 22 and September 21 —Lovejoy did not bend. Instead, he and other religious activists moved to create a statewide Illinois Anti-Slavery Society, and called its initial meeting to be held in Alton. Their cause was only furthered by the national attention and support that the serial mob actions produced. After each dunking, donations came in from around the nation to buy another press. At that point, Usher F. Linder, the attorney general of Illinois, sensed the possibility for political advantage. Much as Van Buren's henchman had broken up the meeting in Utica, Linder took the lead in breaking up the Alton meeting. Unlike the Democrat Van Buren, Linder and his associate Cyrus Edwards, who was angling to become governor, were both Whigs.  Much of this action took place in public meetings, which were at the time a part of the media system in the same way as newspapers. When public meetings were called, there was usually an organizing committee that had already prepared an outcome—a set of resolutions that would be debated and approved— and then an official report would be published in the press. A successful meeting would provide visibility for the positions the organizers pushed. But a public meeting was by definition open to the public. When Lovejoy's group called an antislavery meeting, Linder's followers came, hijacked the meeting, elected their own officers, and passed proslavery resolutions. When a follow-up meeting was called to affirm freedom of the press, Linder's followers hijacked it, too, and passed resolutions calling for Lovejoy to leave town. In dramatic fashion, Lovejoy rose in that meeting to argue his rights; he promised to follow no guide but his conscience, and spoke feelingly of his family and the hardship they suffered. Speaking directly to Attorney-General Under, he said: I plant myself, sir, down on my unquestionable rights, and the question to be decided is, whether I shall be protected in the exercise, and enjoyment of those rights—that is the question, sir; —whether my property shall be protected, whether I shall be suffered to go home to my family at night without being assailed, and threatened with tar and feathers, and assassination; whether my afflicted wife, whose life has been in jeopardy, from continued alarm and excitement, shall night after night be driven from a sick bed into the garret to save her life from the brickbats and violence of the mobs; that sir, is the question. 40

He moved many but could not sway the meeting. Before dawn on 7 November, the Observer's fifth printing press arrived in Alton. Lovejoy's supporters hustled it into a brick warehouse and armed themselves to defend it. After nightfall, the mob gathered. When the attackers tried to climb to the roof and set it on fire, Lovejoy and a companion ventured outside, rifles in hand, to force them off. Lovejoy made an easy target; shot numerous times, he died quickly, two days before his thirty-fifth birthday. Lovejoy's death electrified the nation. Many antislavery activists had been attacked in the free states, but Lovejoy was the first to be killed, and his fate seemed to many moderates to signal a new moment in the struggle against slavery. Abolitionists had fought slavery to protect the human rights of slaves, but now it seemed to many that a greater danger came from slavery's threat to the civil rights of free white men. Traditional freedoms, like freedom of speech and press, could never be secure in a slave society. In 1838, Abraham Lincoln, then a young Whig lawyer and an associate of Usher Under and Cyrus Edwards, broke with them by publishing a lyceum speech on the dangers of mobocracy, a key mile-marker on his road to becoming the Great Emancipator. Without mentioning Alton or Lovejoy by name, he condemned "the increasing disregard for law which pervades the country; the growing disposition to substitute the wild and furious passions, in lieu of the sober judgment of Courts; and the worse than savage mobs, for the executive ministers of justice." And he warned that the greatest danger to freedom in the United States came not from the attacks of outside enemies but from the unleashed passions of its mobs. But Lovejoy's death also showed the intractability of the slavery issue and the incapacity of party politics for dealing with it, a lesson Lincoln was to learn only after much bloodshed. Another noted abolitionist, John Brown, took that lesson immediately. Learning of Lovejoy's death, he determined that only violence would free the slaves, a message he would deliver forcefully at Ossawotamie Creek in Kansas and at Harper's Ferry Virginia, in 1859, the final act in the prelude to the Civil War. 41

Barry L. Witten Main Ideas Teaching the era of the Civil War can be complicated and difficult. Because there is so much to cover in a short period of time, this topic can be difficult for students to understand. An examination of Elijah Lovejoy and his role in the antislavery movement brings in an Illinois connection that many students may have missed in their study of American history. History is often more meaningful when national events of a particular era are connected with the very region in which we live. This lesson certainly forces us to take off our "rose-colored glasses" and focus on the actions of people such as Vice President Martin Van Buren and Illinois Attorney General Usher F. Under. This lesson also helps us to understand how our personal freedom rights have changed over time and how the First Amendment has been interpreted differently over time as well. Finally, this lesson on Elijah Lovejoy will help us to understand how his death electrified the nation and affected the attitudes and actions of people like Abraham Lincoln and John Brown.

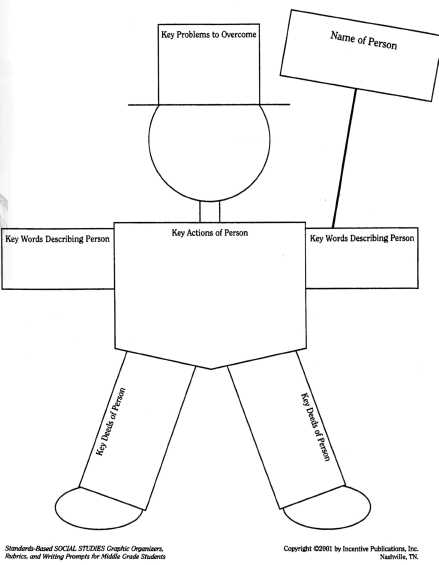

This lesson could be used in a unit in United States history or on local Illinois history. The activities may be appropriate for Illinois Learning Standards 16,16.B, 16.B.4 (US), 16.B.5b (US), 16.D, 16.D.4a (US), and 16.D.4b (US). Teaching Level This lesson has been designed for grades 6—12. The first activity is intended for middle level students, although it could be used effectively with high school students as well. Obviously, older students should be able to demonstrate more depth in the written work requested. Materials for Each Student • A copy of the narrative portion of this article• Copies of each activity sheet • Access to the Internet At the end of instruction, each student should be able to: • Describe the political environment of the 1830s• Identify the attitudes and beliefs of Elijah Lovejoy • Explain the events which led to the death of Elijah Lovejoy • Illustrate how Elijah Lovejoy's death electrified the nation • Examine how Lovejoy's death signaled a new moment in the struggle against slavery SUGGESTIONS FOR TEACHING THE LESSON Introduce the lesson by discussing the importance of communication with your students. Have students brainstorm issues in American history in which different means of communication have been very important, and then assess the importance of communication to the antislavery movement. Newspaper articles, books, and other narratives brought attention to the plight of slaves throughout the land. Newspapers were an especially important means of communication since they were cheap and widely available. Then familiarize your students with Elijah Lovejoy, certainly a compelling journalist of his time. Background information is available in the narrative portion of this article and in the links found at the end of this lesson. To wrap up your introduction, share with students the following quotes attributed to Elijah Lovejoy to get their interpretation and reaction to his situation and to the mood of the region in the 1830s: • 'The voice of three million slaves call upon you to come and unloose the heavy burdens, and let the oppressed go free." • 'The Lord will overrule it [slavery] for the good of black and white, and His own glory." • "I know that I have the right freely to speak and Publish my sentiments, subject only to the laws of the land for the abuse of that right... The contest was commenced here; and here it must be finished ... if I fail, my grave shall be made in Alton." 42 • "What infraction of the law have I been guilty of? When and where have I published anything injurious to the reputation of Alton? ... Why am I waylaid from day to day ... and my life put in jeopardy every hour?" • "Should I attempt it [leaving Alton] I should feel that the angel of the Lord with his flaming sword was pursuing me wherever I went... I here pledge myself to continue it, if need be until death." • Have the students read the narrative portion of this article after your introduction. The article is relatively short and will focus students' attention on the issues you introduced. Have them begin with Activity 1 in which the students will complete the Famous Person Chart on Elijah Lovejoy. This activity was designed for middle level students but it is certainly appropriate for high school students as well. It could be done as a whole class activity, in small groups, or individually. Access to the Internet would be helpful so that students can examine the article by former Illinois Senator Paul Simon referred to in the instructions. You could have students perform a Google search for additional sites if you desire. As a class, have students share their responses as you strive to get to know who Elijah Lovejoy was and understand more deeply his devotion to the antislavery cause. • Since the students have read the article and now have an idea of Elijah Lovejoy's role in the antislavery movement, you will be ready to investigate the Guided Reading Comprehension and Extension Questions in Activity 2. Again, these could be done as a whole class, in small groups, or individually. The last two questions are especially important as we strive to get students to analyze the events that led to Lovejoy's death and the effect that his death had on the abolitionist movement, given that Lovejoy had moved more toward "immediatism" before his death. • The final strategy, the What, So What, Now What activity, is designed for students to complete individually. Make sure that students read the instructions carefully and that you discuss the kinds of responses you will be looking for. It is important for students to understand the impact events such as Lovejoy's murder had on the political climate as early as the 1830s. It is not unusual for teachers to mention the tariffs in passing and then skip to the events of the 1850s such as the Compromise of 1850, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, "Bleeding Kansas," the Dred Scott Decision, etc. Discuss with students important concepts from the reading and the activity sheets. Conclude with a discussion of important anti-slavery leaders of the time such as Lovejoy, Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, and John Brown. What is it about their commitment to the antislavery movement that defines this era in American history? Perhaps the best and most easy to navigate website is the Illinois State Museum's found at http://www.museum.state.il.us/exhibits/athome/ index.html. Students will be able to investigate the settlements of Illinois and the events of the time period from 1800 to 1850. You will find sections entitled: Timeline, Maps, Side by Side, Objects, Clues to the Past, Teacher Resources, and How to Navigate.

To help tie all of the objectives together and provide a special focus on the last two objectives, have the students write a 1 to 2 page essay on the following topic: For this essay you are to assume the role of a person living in Illinois at the time of Lovejoy's death. First, describe your reaction to the circumstances surrounding his death. What were some of your emotions as you heard about the actions of the mob that night? Do you think that Lovejoy's death will electrify the nation? Why or why not? Conclude your essay by explaining how you feel this event has now changed the struggle against slavery. Assess this essay by developing a rubric at the Rubistar website found at http://rubistar.4teachers.org/index.php. Choose "Research and Writing" and either choose a rubric that matches how you wish to assess this essay, or pick and choose from the items in the various rubrics to create your own. 43

44

This activity is designed to introduce you to Elijah Lovejoy and the antislavery movement of the 1830s. It is also designed to help you understand different perspectives and points of view in understanding conflict in American history. You may use the narrative portion of this article to answer the following questions. Be sure to answer each of the items in complete sentences. 1. Beginning in 1833 Elijah Lovejoy edited a newspaper entitled the Observer in St. Louis, Missouri. Why was Lovejoy forced to move the Observer across the river from Missouri into Illinois? 2. Why did the dominant political parties of the time period-the Democrats and the Whigs-want no discussion of slavery published in newspapers throughout the country? What effect do you think this stance had on the nation's mainstream press?

3. In the narrative portion of this article it is mentioned that the antislavery issue could not be suppressed in the cities and towns throughout the young nation. Describe some of the antislavery activities that took place in the mid 1830s. Were you surprised that Martin Van Buren, vice president of the United States at the time, endorsed and may have instigated a riot in Utica, New York, in 1835? Why or why not? 4. The article mentions how Elijah Lovejoy developed his antislavery feelings and attitudes during his conversion, introduction to the ministry, and enrollment at Princeton. How did Elijah Lovejoy develop the Observer into a prominent antislavery newspaper, keeping in mind that there were no wire services, no telegraph, and most newspapers could not afford to hire reporters or correspondents? 5. What does the author mean by "immediatism?" 45

6. How did Lovejoy respond to the pressure applied to him by the citizens of Alton as he continued in his devotion to edit the Observed 7. Who was Usher Linder and what was his role in the break-up of Lovejoy's antislavery meeting 8. What reasons for action or justifications were used by the mob that killed Elijah Lovejoy on November 7,1837? 9. In the narrative portion of this article Lovejoy's death is referred to as "a new moment in the struggle against slavery." What does he mean by this and how do the abolitionists begin to shift their thoughts, attitudes, and motives following Lovejoy's murder? 10. As students of history it is important for us to consider how the issue of freedom of expression has changed over time. Identify a contemporary issue regarding freedom of the press and individual rights. Think about issues that focus on public security, national defense, use of technology, personal safety, and the public's right to know. Discuss what you think are the important points concerning the issue and tell how you think freedom of expression has changed since Lovejoy's time. 46  This chart will organize your thinking after having considered the attitudes, attributes, and accomplishments of Elijah Lovejoy as well as the events that led to his death in 1837. Completion of this What, So What, And Now What? chart will allow us to reflect on what we have learned. In the What column indicate what you learned from the articles you read and the exercises you completed. In the So What column answer the following question: How can the information I learned help me to better understand the rift that was developing between the North and the South in the 1830s? Finally, the And Now What column asks you to consider this question: What can we learn from Elijah Lovejoy about his commitment to the antislavery movement and his devotion to freedom of the press in the midst of intense pressure and imminent danger?

47 |

|

|