|

On January 7, 1862, delegates gathered in the Hall of Representatives at the State Capitol in Springfield for the purpose of revising the Constitution of 1848. Ilinois had enjoyed remarkable growth and prosperity since 1848, yet by 1860, both Democrats and Republicans realized constitutional reforms were necessary in order to meet the needs of a population that had swelled from 850,000 in 1850 to more than 1.7 million. The inflexible Constitution of 1848 fixed salaries of public officials at embarrassingly low levels and did not require legislation to be general, so much of the legislature's time was wasted on private bills, such as corporations and divorces that did not concern the welfare of the state.

Given these deficiencies, the state legislature provided voters with the opportunity to determine whether a convention would be held to frame a new constitution.  In the 1860 election, Illinois voters cast a majority of their votes for Abraham Lincoln in the presidential race, elected a Republican governor, sent a Republican majority to the state legislature, and approved the measure to call a constitutional convention. Lincoln's election to the In the 1860 election, Illinois voters cast a majority of their votes for Abraham Lincoln in the presidential race, elected a Republican governor, sent a Republican majority to the state legislature, and approved the measure to call a constitutional convention. Lincoln's election to the

16

presidency prompted seven southern states to secede from the Union and form the Confederate States of America prior to his inauguration on March 4, 1861. After Confederate forces fired upon Fort Sumter, Lincoln issued a call for troops to suppress the rebellion.

Lincoln's decision to use military force resulted in the secession of four more states, but he received bipartisan support throughout the North. The most notable Democrat to support Lincoln's war to preserve the Union was his long-time political rival, Senator Stephen A. Douglas. Though Lincoln and Douglas had been opponents in the 1858 United States Senate campaign and in the recently concluded presidential election, they agreed that the preservation of the Union was a vital necessity. After endorsing Lincoln's call for troops, Douglas returned to Illinois and rallied the state to the Union cause before his untimely death in June. While there was some appre-hension that the south-ern portion of Illinois, often referred to as "Egypt," would aid the Confederacy, these fears were diminished when prominent politicians from Egypt, particularly John A. Logan and John A. McClernand, entered the Union army.

The state legislature had passed a law in January 1861 that provided for an election in November for delegates to the constitutional convention. Yet as thousands of Illinoisans rushed to meet Lincoln's call for soldiers, attention was naturally focused on the war. Republicans believed that partisan squabbling with Democrats would only aid the rebellion, so they expected that the spirit of unity fostered by the onset of the Civil War would be reflected in the November election and subsequent convention proceedings. This proved to be a very naive miscalculation, as Democrats viewed the constitutional convention as an opportunity to regain the political initiative after the election losses suffered in 1860. While Republicans evinced little interest in the November election for delegates, Democrats mobilized their party apparatus. Of the seventy-five delegates elected, only twenty were affiliated with the Republican Party. Democrats carried forty-five seats, while ten delegates were elected on nonpartisan "Union" tickets, although most of these Union delegates acted like Democrats during the convention.

With a decided majority of delegates, it was obvious that Democrats could control the convention. On the night before the convention's opening session, the Democratic delegates held a caucus that predetermined the officers for the convention. According to plan, when the convention assembled for the first time on January 7,1862, the Democrats had no trouble electing their slate of officers, which included William A. Hacker of Union County as president. Not only was the president of the convention a Democrat from the southern portion of the state, but all the other officers also hailed from Egypt. While this raised some suspicion among Republicans, the actions of the Democrats during the opening days of the convention convinced them that nothing good would come of the proceedings. At best, the Democrats were exploiting the convention as a springboard to revive their party's fortunes. At worst, the convention was an Egyptian conspiracy to destabilize the political situation on the homefront to such an extent that it hindered the war effort.

In the days leading up to the convention, the Illinois State Register, a Democratic newspaper in Springfield edited by Charles H. Lanphier, set the tone for the forthcoming proceedings. Lanphier's paper was very critical of the conduct of Governor Richard Yates and other Republican state officials. In order to meet the emergency created by the outbreak of war, the governor, auditor, and treasurer had authorized spending to equip and supply Illinois soldiers. The Illinois State Register charged that state officials had exceeded their authority and violated the law by spending exorbitant sums that were not appropriated by the legislature. The Register hoped the upcoming constitutional convention would "put all this irregularity into some tangible shape."

From the outset the convention was mired in controversy. Though the legislature had prescribed the oath to be taken by the delegates, Elliott Anthony, a Chicago Republican, expressed reservations about taking an oath of allegiance to both the United States

17

Constitution and the Illinois Constitution. Anthony argued that delegates should not swear an oath to uphold the state constitution when the purpose of the convention was to draft a new constitution. A majority agreed with Anthony's reasoning, and it was determined that delegates would only swear an oath of allegiance to the United States Constitution. While there is little reason to doubt Anthony's sincerity, his successful objection to the legally mandat-ed oath provided a perfect opening for Republican newspapers, such as the Illinois State Journal in Springfield and the Chicago Tribune, to question the conven-tion's legitimacy.

Democratic delegates compounded the controversy over the oath by adopting a report from the Committee on Printing that stated the convention had the authority to appoint its own printer. Just as the legislature had prescribed the oath for the convention, it had also designated the secretary of state as the convention's printer. While the appointment of a printer was not an especially controversial issue in itself, the majority report of the Committee on Printing also maintained that only the United States Constitution limited the convention's authority. Though Elliott Anthony had led the move to alter the oath, he submitted a dissenting report that argued it was "revolutionary" for the convention to assume such powers. The convention was essentially asserting its supremacy over the duly elected state government and, for Anthony, this represented "usurpation." Despite the objections of Republicans, the majority report was adopted by a decisive vote, and the convention then proceeded to appoint Charles H. Lanphier as its official printer.

Emboldened by the belief that they possessed almost unlimited power, Democratic delegates attempted to embarrass Governor Yates as much as possible. The convention demanded numerous reports from Yates and other state officials regarding military and financial affairs, especially documentation pertaining to contracts for army supplies. Clearly, Democrats hoped to unearth evidence of corruption, and a special committee to investigate military affairs was appointed and placed under the direction of James W. Singleton, a prominent Democrat who had served as a delegate to the previous constitutional convention. Singleton's committee conducted a thorough inquiry and even sent a letter to the commanding officer of each Illinois regiment that asked whether the soldiers were adequately supplied. While most officers complied with the request, some recognized the Singleton Committee as a blatant attempt to damage the credibility of the Republican administration. One such officer was Major Quincy McNeil of the Second Illinois Cavalry who bluntly informed Singleton: "Should I give you the information ... I should make as great an ass of myself as the Convention has of you by asking you to attend to that which is none of your business, and which is also not the business of the Convention." Though Democrats hoped the Singleton Committee would humiliate the governor, the final report concluded that Illinois soldiers were as well, if not better, equipped than soldiers from other states.

During its first month in session the convention devoted so much attention to resolutions and political issues unrelated to the business of drafting a new constitution that the Illinois State Journal sarcastically predicted the convention would not conclude before 1870. E.P. Ferry, a Republican delegate from Lake County, observed that the war was such a distracting influence it would have been "impossible to have selected a time more unfortunate" for a convention. Ferry, with the hearty endorsement of the Republican press, proposed that the convention adjourn until June in the hope that the war might be over by then. His motion was soundly defeated, and the convention proceeded to act as if it possessed legislative powers. New districts for the state legislature were drawn, and the Democratic majority also reapportioned the state's congressional districts and ratified an amendment to the United States Constitution that would have prevented Congress from interfering with slavery in the states. In one of

18

its numerous demands for information from the governor, the convention presumed to "instruct" him on how to act. Yates protested that the convention had no authority to instruct him, while the Illinois State Journal detected the origins of a coup d'etat in this semantic confrontation.

As the convention continued its work, Illinois regiments participated in the resounding victories at Forts Henry and Donelson in Tennessee. When news of Fort Henry's surrender reached Springfield on February 7, Elliott Anthony immediately introduced a resolution praising the victory. But some Democrats objected to the language of the resolution, and the matter was referred to a special committee. Republicans had already become quite cynical about the real intentions of the Democratic delegates, and when the Fort Henry resolution was not instantly passed by a unanimous vote, the Chicago Tribune printed a dispatch from its Springfield reporter claiming that some of the Democratic delegates were members of a secret organization aiding the Confederacy. The convention took exception to those charges, and a committee was appointed to investigate whether any of its members were disloyal. Though the committee found nothing to substantiate the charges, Republican newspapers continued to claim that the convention was controlled by a mob of rebel sympathizers. On February 17, news of Fort Donelson's fall created such a sensation that people rejoiced in the streets as bells rang and cannons boomed. The convention had learned a lesson from the controversy over the Fort Henry resolution, as it promptly adopted a resolution expressing its "unbounded gratification" for the surrender of Fort Donelson and adjourned for the rest of the day so that delegates could join in the revelry.

Sensitive to the charge of disloyalty, the convention passed an ordinance on the day following the Fort Donelson celebration that authorized the sale of $500,000 in state bonds for the purpose of aiding Illinois soldiers who had been wounded in battle. Republicans denounced this move as an impractical scheme "prompted more by buncombe than by genuine patriotism." State officials ignored that ordinance, along with additional ordinances that restricted the operation of banks and impeded the collection of federal taxes. The passage of ordinances tended to contradict the convention's obligation to submit its work to the people for their approval and provided Republican newspapers with the pretext to condemn the Democratic majority as an oligarchy of "broken down hacks" that was attempting to resurrect a "defunct political organization" by usurping the will of the people. Lanphier's Register retorted that Republican attacks upon the convention were merely attempts to detract attention from the "plundering schemes of the state administration."

In spite of the numerous distractions and intense partisan bickering, the convention managed to fulfill its obligation by drafting a new constitution. The proposed constitution gave the legislature discretion to determine salaries for state officials, allowed general legislation in some instances, and included a provision requiring all bills to be read in their entirety on three separate days in a further attempt to curb the bane of private legislation. The new constitution also increased the number of judicial districts, reinstituted the office of county attorney, and eliminated the two-mill tax. One of the most controversial aspects of the constitution was the reduction of the term in office for state officials from four years to two. If voters approved the constitution, Governor Yates would face a Democratic challenger in November 1862 instead of 1864.

The convention also appended articles to the constitution that were to be voted on separately. These included a provision that virtually eliminated all banks in the state by 1866, a reapportionment of congressional districts, and three articles concerning the status of African-Americans. The rights of persons of color played a conspicuous role in the convention, because some Democrats were not satisfied with the 1853 law that made it illegal for blacks to settle in Illinois, while others hoped the issue would aid in drawing a distinction between the two parties. Milton Bartley, a delegate from Egypt, deemed the 1853 statute inadequate, yet he failed to persuade the convention to grant individual counties the power to "remove all negroes and mulattoes from the limits of any such county." Bartley had to settle for articles that prohibited persons of color from settling in Illinois, denied them voting rights, and

19

directed the legislature to pass laws necessary to enforce those provisions. Most Republicans opposed the ban upon African-American settlement in Illinois, but there was little support for the idea that persons of color should receive civil rights. Only seven delegates voted against the article that proscribed African-American suffrage, and as further evidence of the prevailing sentiment, an alleged fugitive slave was apprehended in Springfield and returned to a Missouri slaveholder without incident while the convention was in session.

Most Republican delegates had already left Springfield by the time the convention ended on March 24, and only three Republicans agreed to affix their names on the new constitution. The convention concluded by authorizing the printing of thousands of copies of the new constitution and issuing an address to the citizens of Illinois that urged them to ratify the constitution and the five additional articles in the referendum that would be held on June 17.

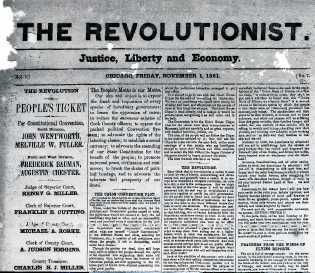

In the three months between the end of the convention and the plebiscite, newspapers and stump speakers for both parties engaged in a bitter war of words. The Republican campaign against ratification had actually begun during the opening weeks of the convention when the Democratic delegates made it clear they were going to use the convention as a means to regain political power. The Illinois State Journal and Chicago Tribune took the lead in denouncing the proposed constitution as an "outrageous political swindle" that had been concocted by an Egyptian, pro-slavery, pro-Confederate conspiracy. Indeed, the convention's reapportionment of state legislative districts and congressional districts favored the heavily Democratic southern portion of the state. Democrats countered with the argument that the new constitution was a document that would substantially improve the lot of the common man by reducing taxes and curbing the power of large corporate interests such as banks and railroads.

More than 250,000 Illinoisans went to the polls on June 17, and the new constitution was defeated by a margin of 16,000 votes. The separate articles on banking and congressional apportionment were also defeated; however, the three articles concerning African-Americans were overwhelmingly approved. Each of the articles received a majority of over 100,000 votes, with the article against black suffrage being the most popular. In Lincoln's hometown of Springfield the article received over 2,000 votes, while only 20 voted against it. The convention had made arrangements for Illinois soldiers to vote by appointing three commissioners to travel to the various camps and record the votes. With tens of thousands of soldiers in the field, the commission was able to canvass only a small fraction of the soldiers before the August deadline. Despite Democratic hopes that the soldier vote would prove to be the decisive factor in the election, more than 5,000 soldiers voted against the constitution and fewer than 2,000 supported it.

Exit polls do not exist for this era, so one must speculate on why the people voted the way they did. The controversy over slavery in Kansas during the 1850s and the more recent secession crisis had demonstrated both the fragile nature of self-government and the perils of conventions. The people of Illinois had sent more than 60,000 of their sons, brothers, husbands, and fathers into the army, and the 1862 constitutional convention was an unwelcome distraction from the vital issues of the day. The Constitution of 1848 was in need of reform, and if the convention had concentrated more on the task of drafting a new constitution and less on trying to embarrass a popular wartime governor and putting Democrats back in power, then both the product of the convention and the result of the referendum might have been much different.

Mindy Juriga

The Role of Political Parties in Illinois

During the 1862 Illinois

Constitutional

Convention

Overview

Main Ideas

The Civil War was a time of great turmoil. Because Abraham Lincoln hailed from Illinois, many people assume that the state was united on the issues of the Union and slavery. However, at the Constitutional Convention of 1862 it was clear that not all Illinoisans shared the same views. While Republicans were concerned with adopting a new state constitution and then supporting the troops in the war effort, the Democrats seemed to be focused on promoting their political party. In this lesson students will read the article "A Government for the People or an Egyptian Swindle?: The 1862 Illinois Constitutional Convention." After reading the article students will research where each party stood at the onset of the Civil War in Illinois and at the start of the 1862 Illinois Constitutional Convention. Students will then write persuasive essays supporting either the Democrat or the Republicans efforts.

Connection with the Curriculum

Students throughout the state of Illinois

20

are required to learn state history and Civil War history. This lesson ideally fits in with a Civil War unit, but would also fit in an Illinois history unit dealing primarily with the Illinois Constitution and/or Illinois in the Civil War. The narrative and activities may be appropriate for the following Illinois Learning Standards: 16A. 4b, 3c; 16B. 3a, 4a, 5a; and 16D. 4a, 4b.

Teaching Level

Grades 7-9.

Materials for Each Student

-- A copy of the narrative portion of this article

-- Access to computers with Internet access for both research and word processing

-- Any relevant reference materials from the library could also be helpful

Objectives for Each Student

-- Each student will be able to determine where both the Democrats and Republicans stood at the time of the 1862 Illinois Constitutional Convention

-- Students will individually decide to support the efforts of the Democrats or the Republicans

-- Students should produce a thesis statement that they will submit to their teacher for approval

-- Students will provide a detailed outline before word processing begins

Opening the Lesson

Teachers should introduce students to the turmoil our country was facing at the onset of the Civil War. Point out that the unique situation Illinois was in because of the newly elected president from Illinois, Abraham Lincoln. Discuss how the timing of the 1862 Illinois Constitutional Convention may not have been the best time to discuss changes to the state constitution. Next, have the students read the article individually or as a class. This should be followed by a class discussion on both sides of the issue (Republican and Democratic).

Developing the Lesson

As students discuss and begin to learn more about this time period in both the nation's and the state's history, begin guiding them to form an opinion on the direction and intentions of both political parties. Have students do some research on the Internet and in the library to learn more about these political parties at this time. Also, encourage them to find out why legislators felt the need to make changes to the state constitution. Once students have a good grasp of the material, have them submit a thesis statement that will be the basis for their persuasive essay. Upon teacher approval of the thesis statement, students can begin the writing process beginning with a detailed outline.

Concluding the Lesson

Students will submit a three-to-four page persuasive essay

Extending the Lesson

After the essay is submitted, this would be the perfect time to go full force into a Civil War unit with the students, discussing the state of the nation at this time while also keeping tabs on the role that Illinois specifically played in the Civil War.

Assessing the Lesson

Assessment will be conducted in stages throughout this lesson. The first assessment will be when the teacher feels that the students are ready to begin research and writing on this topic. The teacher can assess this by basic classroom discussion of the article. Next, it is important for the teacher to approve the thesis statements that each individual student submits. This will also help to gauge, on individual basis, if the student understands the topic and the assignment. Lastly, a standard persuasive essay rubric can be used to assess the final paper.

The Role of Media in 1862

Overview

Main Ideas

Soon after Abraham Lincoln of Illinois was inaugurated as president of the United States in 1861, legislators in Illinois began discussing changes that needed to be made to the Illinois Constitution. Also, during this time the country was at the onset of a devastating Civil War. In 1862 an Illinois Constitutional Convention convened to make some changes to the state constitution, and even while the legislators were meeting many citizens questioned why they were focusing on the state constitution instead of the state's role in the Civil War. Much of the communication about the convention took place through politically charged newspapers in Illinois. In this lesson, students will work in groups to create a copy of a newspaper in 1862 covering both the Illinois Constitutional Convention and the war.

21

Newspapers can either be examples of the Illinois State Register (a Democratic newspaper in Springfield), the Chicago Tribune (Republican newspaper at this time), and the Chicago Times (available through most local libraries and university libraries).

Connection with the Curriculum

Students throughout the state of Illinois are required to learn state history and Civil War history. This lesson ideally fits in with a Civil War unit, but would also fit in an Illinois History unit dealing primarily with the Illinois Constitution and/or Illinois in the Civil War. This lesson also explores the role of the print media. The narrative and activities may be applicable for Illinois Learning Standards 16A. 4b, 3c; 16A. 3a, 4a, 5a; and 16D. 4a, 4b.

Teaching Level

Grades 7-9.

Materials for Each Student

-- A copy of the narrative portion of this article

-- Several copies of newspaper headlines and articles both current and in the past. Any Civil War-era newspaper headlines and articles would be most helpful for students to better understand the time period. It may be possible to access such articles and headlines on the Internet and through library reference materials. Furthermore, contacting the special collections section of a nearby university library might provide access to original documents for the students to view.

-- Large 11" x17" art paper or parchment paper to use for their newspapers. NOTE: In order to make plain art paper look "authentic" the paper can be soaked in tea. This will give it an aged look.

Objectives for Each Student

-- Gain a better understanding of the role print media played in 1862 by researching primary source documents

-- Learn how to structure a newspaper; students will create catchy headlines and intriguing articles. This can be done both by researching primary sources as well as current newspaper set-ups.

Opening the Lesson

Start a class discussion of how newspapers influence the way people feel about political issues. Speculate, in class discussion, on the role newspapers have played in the past regarding political issues and specifically the Civil War. Next, as a class or individually, read the article "A Government for the People or an Egyptian Swindle?: The 1862 Illinois Constitutional Convention." Discuss the role of the media in the convention.

Developing the Lesson

Students should have access to primary source documents (newspapers of the time), or at least access to Web sites that would provide samples of primary source documents. Allow some time for students to research and learn how newspapers were (and are) set up. Guide them to focus on headlines, articles, and layout of the papers. Tell them that they will be required to put together a sample of a Civil War-era newspaper in Illinois. They will be covering both the Constitutional Convention and the role Illinois played in the war. Students should do some research (taking notes) on each of these topics as they prepare to produce their own newspapers. After students have done the research, place them into groups of two or three to work together on this project. Allow the students several class periods to physically put the paper together. Encourage them to make their newspapers look as authentic as possible either by using parchment paper or tea-dying their paper.

Concluding the Lesson

After the newspapers are finished, have each group present their newspaper to the class (this doesn't have to be a long presentation, just get them talking about the construction of their project). Discuss with students how they see media continuing to play a large role in political issues today. Discuss ways in which media has evolved over time as well.

Extending the Lesson

Speculate on how things might have been different if newspapers did not cover the Convention of 1862 or the Civil War.

Assessing the Lesson

Teachers should monitor class discussion in order to see if the students are ready to begin the project. After the project has begun, teachers should continuously monitor the research process, making sure that students are understanding the information and are headed in the right direction. Once the newspaper is complete, a project rubric can be developed taking into consideration individual teacher requirements for the newspaper.

22

|