Robert D. Sampson

Historical Research and Narrative

On a late winter night in 1862 a Mount Zion schoolhouse was packed for a speech by Civil War hero Richard James Oglesby. Standing before the American flag, Oglesby rhetorically wrapped himself in the Stars and Stripes as he lashed those who would divide the Union. "Do you know that there are men in the county who have left their families and are now fighting in the rebel ranks?" the wounded veteran shouted. One in the audience who did know, cried out, "Close neighbor, too."

Yet more than fears that some neighbors might be serving under the Confederate Stars and Bars banner were troubling the enthusiastic audience. They were worried about support for the war in places like Mount Zion, a village a few miles southeast of Decatur, other rural neighborhoods, or even Decatur itself. "I have more respect for a rebel in arms than for that mean, contemptible man who stays at home talking about the constitutionality of this act, or that act," Oglesby confessed. Those who really disturbed him were individuals trying to make "political capital" out of "habeas corpus" (referring to frequent Democratic complaints about Lincoln's suspension of civil liberties) or who encouraged men to resist the draft. "And they try to make us believe that the Democratic Party is with them. I do not believe it. I never shall believe it," Oglesby bellowed.

True Democrats, he said, would never behave in such a manner. And for those who did, "Call those democrats! They are no democrats. They are Democratic devils." The crowd responded by nearly shouting itself hoarse; one man later recalled cheering like never before in his life.

A skilled politician, Oglesby shifted gears after consigning one wing of the Democracy to Hades, switching to the high road of nonparti-sanship. Though he had already been elected (in 1860) to the Illinois Senate as a Republican, Oglesby claimed to have no party, speaking kindly of those Democrats who supported the war and the Lincoln administration. "If I was a democrat, I would be one; but I would not make that party above my country. I would support no man who would dissuade me from that party. You cannot kill off the party."

Ironically, Oglesby would spend the next three decades (he later served as governor and U. S. senator) helping to kill off the electoral prospects of the Democrats in Macon County, the state, and the nation. His skillful blend of humor, outrage, and patriotism in the Mount Zion speech was likely played out thousands of times across the North by other speakers as the Republican Party and the Lincoln administration struggled to preserve not only the Union but also their hold on government.

While blood flowed across the battlefields, the young Republican Party was not shy about tarring its opponents with charges of treason.

23

Democrats in Macon County and throughout the North proved unable to consistently overcome such attacks, as the party continued its slide to minority status in the region through the 1860s. Oglesby's speech and, importantly, its location, provide a glimpse of the wartime tensions and political shifts that would change Macon County from a reliable supporter of the Democracy to bedrock of central Illinois Republicanism.

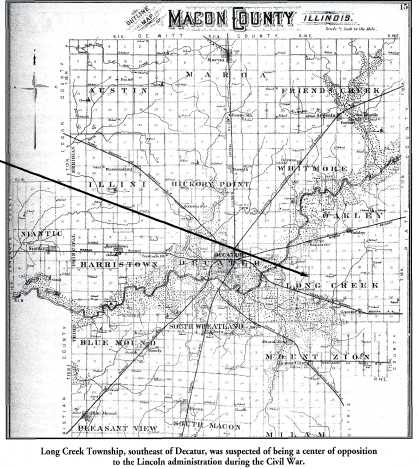

Oglesby likely picked Mount Zion to give his fiery speech because it adjoined Long Creek Township, reportedly a hotbed of anti-Lincoln administration activity during the war. Some Long Creek residents, it was alleged, held secret meetings to oppose the draft and to conduct military drills. At one point, the township's dissenters held an open-air rally. Oglesby had the misfortune to pass by the meeting just as it reached its climactic point. He was quickly surrounded by armed citizens. Only by returning the crowd's curses "with interest," was Oglesby able to escape.

Since the last shot of the Civil War was fired, most historical attention has focused on the victors of the North or the losers of the South. But in the late-twentieth century some scholars began to examine the Northern Democrats, especially those who attempted to maintain their political creed among changing voting habits and partisan condemnation. Events in Macon County between 1860 and 1868 paint a vivid portrait in miniature of the shifts in political allegiance occurring across the Northern political landscape.

During this period a Democratic newspaper editor whose partisan credentials had been impeccable, diluted his rhetoric to "milk and

24

water consistency." Another Democratic editor paid for his ideological purity—and lack of tact—by being mobbed twice—once in the streets of Decatur and a second time outside his journal's office in Maroa—and driven from the county.

Even before the Civil War arrived, Macon County was experiencing sweeping changes. In 1850 it had 3,988 residents. Ten years later the population had boomed to 13,655 citizens, a spurt helped in large part by the intersection of two railroads-the Illinois Central and the Great Western-at Decatur, the county seat. Decatur, with 3,839 residents in 1860, was nearly as big as the whole county had been ten years earlier.

Behind the numbers lay another dramatic shift. From its founding in 1829 until the 1850s, the majority of Macon County's residents were of Southern background. People with New England antecedents began arriving in greater numbers with the railroad boom, likely further aggravating cultural tensions between the two groups extending back decades in Illinois and, locally, to the creation of Macon County and selection of the county seat.

While there were numerous exceptions to the rule—Lincoln and Oglesby among the most prominent—those with Southern backgrounds tended to support the Democracy and exhibit more uncertainty about the sweeping economic changes wrought by the market economy and the railroads.

Long Creek Township, site of Oglesby's close call, had a high proportion of residents by 1860 who were either born in the South or married to a Southerner, or who were the offspring of parents born in the South or lived in a Southern-dominated household. In 1860, 262 of the township's 583 residents fell into that category. Two other rural townships— Niantic and Harristown—also associated with alleged anti-war activities, fell into this category. By contrast, in Decatur's Ward Three, only 297 of 909 residents fell into the Southern group. Long Creek Township, site of Oglesby's close call, had a high proportion of residents by 1860 who were either born in the South or married to a Southerner, or who were the offspring of parents born in the South or lived in a Southern-dominated household. In 1860, 262 of the township's 583 residents fell into that category. Two other rural townships— Niantic and Harristown—also associated with alleged anti-war activities, fell into this category. By contrast, in Decatur's Ward Three, only 297 of 909 residents fell into the Southern group.

Prior to the presidential election of 1860, Illinois was the Democratic Party's most dependable friend in the Old Northwest, clinging to its presidential candidates even through the party's defeats in 1840 and 1848. Like Illinois Democrats, Macon County Democrats forged a steady stream of electoral triumphs, from the first election in 1830 right up to and through the presidential election of 1860, which saw Douglas top Lincoln by 40 votes. Even in Oglesby's successful state senate bid in the 1860s, he lost his home county by six votes.

Macon County Democrats also had a strong advantage on the newspaper front at a time when most citizens received their political information from openly partisan national and local papers. Democrats could pick between two party organs in Macon County. One represented the Douglas wing of the party; the other the faction aligned with President James Buchanan and were derisively known as "Buchaneers." Each of those newspapers had double the circulation of the lone Republican voice, the Illinois State Chronicle.

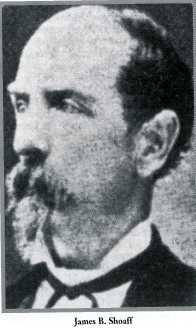

Leading the "Buchaneer" journal, the Magnet, was an already legendary figure in Macon County journalism, James B. Shoaff. A former mayor of Decatur, Shoaff founded the county's first newspaper, the Gazette, which by 1860 was the journal of the Douglas faction. In 1860, Shoaff's Magnet favored just about any Democrat for the presidency save Douglas. The Gazette, of course, backed the Little Giant. Fighting for the Republicans was William J. Usrey and his Chronicle.

When the Civil War began, the Gazette followed Douglas in supporting the war and, after the senator's death, became a War Democrat newspaper. What limited editorial opposition there was came from Shoaff's

25

Magnet, with the Chronicle, led during the war by J.R. Mosser, dispensing rhetorical cannonades on behalf of Lincoln. A sign of Mosser's effectiveness was his appointment as state printer after Oglesby was elected governor in 1864.

At first, Shoaff fired back at those who questioned the patriotism of Democrats, including famed New York City editor Horace Greeley, who had charged that Democrats were carrying out the wishes of the Southern rebels. "To be a democrat is to be loyal to the constitution and the Union, and the party will fight on no other platform," Shoaff's Magnet responded. But as the war progressed, such sentiments faced increasing assault from Republican and War Democrat editors in Decatur and Springfield who maintained that anything less than unequivocal support for the Lincoln administration was, as Oglesby inferred in Mount Zion, tantamount to treason. However, in the first election after the November 1860 presidential balloting, Macon County Democrats had reason to celebrate. The party's candidates for delegate to the state constitutional convention were victorious in the district that included Macon, DeWitt, Piatt, and Champaign counties. And, in 1862, the party reaped the benefit of growing dissatisfaction with the war and associated economic and social stress as its candidates won stunning victories throughout the North, including Lincoln's home congressional district and another that included Macon County. Bucking the Democratic tide, though, was Macon, which in reversal of its past electoral behavior gave Republican candidates for all offices a 300-vote plurality. It was to be the first in a long succession of victories for the party of Lincoln and Oglesby.

Taking a break from extolling the virtues of their respective candidates and the vices of the opposition, editors in Decatur and Springfield debated about which party was providing the bulk of the Union army's manpower. The War Democrat Gazette fired the first shot when it claimed that the army's "regiments are composed principally of Democrats." Outraged, the Republican Chronicle sniffed, "The Democracy cannot do too much to relieve herself of the odium of furnishing all the traitors in the loyal states" before going on to submit the Mexican War, repeal of the Missouri Compromise, "bleeding" Kansas, and Buchanan's final months in office as sufficient proof of the Democratic Party's responsibility for the war. The Illinois State Register, the Democratic organ in Springfield, joined the fray, claiming that the reason why the Democracy's vote totals were dropping in Macon County was because more than 4,000 of its Democrats were serving in the Union army.

In fact, Macon County Republicans were sensitive to the charge that it was a Republican war and a Democratic fight. Decades later, the wife of a prominent Decatur Republican revealed that a number of wealthy Decatur men who had purchased the exemptions possible under the draft law, quietly provided support for the families of men who had enlisted. She named Decatur banker and later college founder James Millikin as among that group.

When it came to the home front, the Chronicle took the lead in calling for an organization of Union men in each of the county's townships to "ferret out the names and doings of all sympathizers with treason." Reports continued to circulate through the county of "traitors" at home who were conducting military drills and plotting unknown outrages. History, however, records no overt act to justify such rumors.

As the Civil war raged on, the War Democrat Gazette and the Republican Chronicle sounded minor variations on the same tune. Fusion tickets of War Democrats and Republicans swept elections for mayor and other offices in Decatur. At the Magnet, Shoaff tried for a time to hold out. By September of 1863, the paper was publishing daily. In 1862, it had come out for New York Governor Horatio Seymour as the party's candidate for president in 1864 with General George McClellan as his running mate. Their names floated atop the newspaper's editorial page masthead until the New York City Draft Riots in July 1863, after which Seymour's name disappeared. Shoaff was clearly a businessman first and a Democrat second, explaining why his editorial support of the Democracy all but disappeared by war's end. The elections of 1864 saw even stronger Republican victory margins in Macon County, a clear indication of which way the political winds were blowing. By February 1865, Shoaff's newspaper was even supporting a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery. In July of the same year, he portrayed himself as a long-time supporter of the war. Two years later, when a new journal, the Decatur Republican, edited by Mosser took up the Republican standard, Shoaff had words of praise. By April 1868, Shoaff promised readers that he would keep politics out of his journal. And the tactic paid off. In August, the Republican-dominated Macon County Board awarded Shoaff the county's printing. This sort

26

of behavior led to Shoaff's condemnation by a firebrand Democratic editor in Maroa, the county's northernmost village. In peddling his "milk and water" version of the Democracy, Shoaff had "sold the Democratic party of Macon county [sic], but thank God, failed to deliver it."

The author of the charge was Thomas Jefferson Sharp, a mysterious, colorful individual who for a few months in 1867 published the Maroa Times. Sharp moved to Maroa, a village on the northern edge of Macon County, after a disastrous attempt to expound his vitriolic version of the Democracy in Clinton. He seems to have generated personal quarrels, animosities, and inflammatory statements at a more productive rate than he ever did profits. His editorials bristled with the white supremacy typical of the era's Democratic ideology along with the fundamentalist tenets of the Jacksonian era—free trade, equal rights (for whites) and condemnation of wealthy capitalists who exploited workers and farmers. Sharp, who claimed to have served in the Union army, did not let attacks on his patriotism go unanswered, and his replies tended to double the venom directed at him. He also delighted in chances to tweak his editorial opponents, especially their vanity.

A regular feature of Mosser's Republican was an account of a visit to some small county village or the other that would extol its attributes. Sharp decided to visit Decatur.

"We had occasion to visit this driving village the other day," he wrote. "Decatur is a large place! It is one and half size larger than London-almost as large as Boston. It is a long way from Maroa." He referred to Oglesby, then-governor, as "Big Dick" and a "profane cuss." Decatur, he continued, "is a poor place for dogs to run at large, it is easy for 'em to get lost, especially if they're country dogs." "Decatur," he concluded, "is a good place to go if you don't stay too long."

Words like these might redden the face of a rival editor or local booster. Other words, however, could provoke more drastic action. In a section of his newspaper headed "Decatur Items," Sharp took notice that a military unit was soon to be organized in the city "the object of which, we presume, is to be prepared to guard the polls in '68 to prevent democrats from voting." A few weeks later, the unit known as the Decatur Zouaves under the command of John H. Nale, was formed. Under the headline "Wanted More Blood," Sharp penned three sentences about the company that opened a nasty wound to the city's pride:

"We see by the Decatur papers that a company of soldiers have been organized, and are soon to be equipped. It is to be commanded by a red-mouthed knave who is guilty of murdering an old man and his wife during the war, a few miles south of Decatur. The object of this company is to hunt down poor innocent women and children, murder them in cold blood, to pillage the country, arrest Democrats, and guard the polls in '68."

A few days later when the Decatur Republican reprinted the item, most people in Decatur and, especially Nale and those who served with him in the war, knew exactly what Sharp meant. Throughout the summer of 1864, tales of a band of Confederate marauders terrorizing Montgomery County repeatedly circulated. Finally, a company of Illinois soldiers then on furlough in Decatur was dispatched by Governor Richard Yates to capture the supposed raiders. Nale, who led the group and his men, had been through hard, bloody, and costly fighting a year earlier in battles around Jackson, Mississippi. They had learned to quickly react to perceived threats or run the

27

risk of joining the 32 of their 200 comrades killed in Mississippi. At the end of a long and frustrating day chasing phantom raiders, Nale and his men approached the farmhouse of 68-year-old Johnny Sears, a veteran of the Battle of New Orleans. When Nale demanded a saddle, Sears refused and, according to Nale's account, pulled a gun and began firing at the soldiers. Nale and his men returned fire, killing Sears and his 75-year-old wife who was standing beside him. Then, according to later accounts, they rode off, leaving the bodies of the elderly couple lying where they fell in the doorway of their home.

Sharp's comments publicizing this incident provoked immediate outrage in the Decatur newspapers. The nomi-nally Democratic Shoaff expressed more anger than the Republican Mosser. Shoaff termed Sharp's article a "willful and cowardly" attack. Four days after Sharp's article appear, Nale and some friends took more direct action As Sharp ventured into Decatur to attend a baseball tournament, Nale and his friends surrounded the editor at a downtown intersection. As Nale began striking Sharp from the rear, others in the former soldier's party joined in. Sharp later estimated the number at 40. Somehow, Sharp was able to break away and dashed into a nearby store for safety. When his attackers followed, he ran back into the street, through the back door of a saloon, and, eventually, found refuge in the post office. There, Decatur's Republican mayor rescued Sharp, taking the editor to his home until tempers cooled and Sharp could safely return to Maroa.

Maroa itself proved no friendlier to Sharp. Several weeks later as he walked in the street near his newspaper office, Sharp was knocked senseless by a stone "hurled at him by some unknown person." Several arrests were made in connection with the Maroa incident, but it proved the final straw for the editor. Sharp packed up and moved—amazingly—to Republican Logan County, where his new journal, Sharp's Daily Statesman, was published apparently without incident.

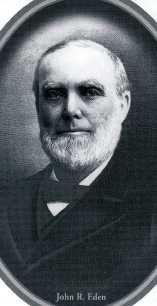

By the election of 1868, Macon County Democrats realized they were fighting for their lives. Attempts to bring in a more effective Democratic editor than Shoaff failed. After the wartime fusion of War Democrats and Republicans broke down, the Republicans took all the local offices. Democrats placed hope for a comeback on the 1868 election. A few days before the ction, a large parade and outdoor rally was planned, complete with several orators, including the party's candidate for governor, former congressman and the party's candidate for governor John R. Eden of Sullivan. Justifiably, Macon County's Democrats might have thought even the gods were arrayed against them when the weather turned nasty. After canceling the outdoor rally, party leaders approached the Republicans, hoping to rent their hall. When refused, Democrats were literally back in the streets. Mud and blustery, cold winds mired and buffeted the hardy band that assembled to hear the speakers.

Shoaff had approached the election with his usual lukewarm support for the party. "The issues are all made up," he editorialized in the last days. "The candidates are all in the field. Choose, ye, therefore, whom ye shall serve." He did predict the triumph of Democratic principles while refraining from mentioning those who embodied them.

Even a fighting Democratic editor would have made little difference. On Election Day, the party's candidates lost in Macon County by 500 plus vote margins. By 1868, Macon County Democrats were a beleaguered minority at home. For Macon County Democrats in the days after the 1868 election, it must have

28

seemed that the world had turned upside down. In only a few short years, their dependable majorities were transformed into regular margins of defeat. Changing demographics account for some of the reversal. Perhaps even without the upheaval of civil war, the steady migration of commercial-minded settlers from New England and the central states might have turned the county's political complexion.

War, however, played a major role. Many veterans who left for the army Democrats returned home to vote as they shot. Late nineteenth-century county histories provide glimpses of these men, who refer to their pre-war politics as Democratic and their post-war preferences as Republican.

Racked by party factionalism, hampered by an erratic and lackluster press, and unable to counter the "bloody shirt" rhetoric of their opponents, Macon County Democrats found to their dismay that their day as a majority party had passed. Those who remained, however, stayed loyal to the faith. To paraphrase a contemporary description cited by one historian of the Civil War Democracy, loyal Macon County Democrats lived and died in the faith of their fathers, vainly hoping for a day when the party of Andrew Jackson and Stephen Douglas would once again be triumphant.

Thomas Best

Overview

Main Ideas

Artillery did not always deliver the most damaging salvos experienced during the Civil War. Launched from the lips of skilled orators and pens of caustic newspaper editors were equally destructive pejorative characterizations, damning criticisms, and stinging metaphors. While this war of words was witnessed in many venues across Illinois, the narrative portion of the article provides vivid specifics of the battle that affected the political landscape of Macon County. Whether challenging the loyalty of local residents or questioning the right of the Lincoln administration to limit the civil liberties of its citizens, the legacy of conflict between Civil War-era Democrats and Republicans in Macon County reveals how the fundamental democratic principles can be severely tested in times of great chaos and ideological polarization. Teachers may therefore use this narrative of political combat as: 1) a microcosm for the study of the Civil War on the Illinois home front; and 2) as a catalyst for further research and creative expression of historical understanding for both Macon County and their own locality.

Connection with the Curriculum

This lesson can be taught either as part of a lesson on the history of the Civil War or as an era in Illinois history. Specific Illinois standards that may apply to these lesson ideas are: 14.8.09—the identification of the evolution, function and tenets of political parties; 16.8.04—recognizing the differences of two interpretations/points of view of a single historical event and differentiating between unsupported expressions of opinion and informed hypotheses grounded in historical evidence and reasoning; 16.8.23—identifying economic, social, and political causes of the Civil War; and 16.8.24—understanding the major developments of the Civil War (including political and military events).

Teaching Level

These activities, while most appropriate for high school age students, could be modified for middle school or junior high schools by an editing of the previous narrative or selectively choosing one or more elements of these lessons. All of these activities are intended to challenge students' ability to read and interpret such political issues and events.

Materials for Each Student

-- A copy of the narrative portion of this article

-- A copy of the student handouts appropriate to the age group

-- A United States history textbook for background reading and glossary

-- Internet addresses for additional resources and research

-- Contemporary newspapers, magazines, television broadcasts, and Internet sites

-- County history books and histories of the state of Illinois

Objectives for Each Student

-- Define the following terms: Democrat, Republican, habeas corpus, partisan, dissent, patriotism, platform, editorial, orator, demographics, and "bloody shirt"

-- Recognize the wartime role of the following people: Richard Ogelsby, Horace Greeley, and George McClellan

-- Explain what role the demographic origins of citizens had upon political allegiance during and after the Civil War

29

-- Describe the ideology and issues that separated political supporters of the Democratic and Republican parties during and after the era of the fighting of the Civil War

-- Examine primary sources, ranging from speeches to newspapers, to locate examples of factual statements and partisan points of view from political speakers and writers

-- Produce a creative expression of the drama and charged atmosphere of the era in Macon County through skits, letters, drawings, political cartoons, and/or newspaper editorials

-- Draw comparisons about partisan conflict during the Civil War to other wars and political conflicts in other eras of American and world history

Opening the Lesson

1. Assist the students in defining the following terms and concepts used in the article: Democrat, Republican, habeas corpus, partisan, dissent, patriotism, platform, editorial, orator, demographics, "bloody shirt," and propaganda. Unless teachers want students to research and discover the wartime roles of Richard Oglesby, Horace Greeley, and George McClellan as they read, these individuals could be introduced to students at this point.

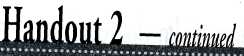

2. Students should read the narrative section of this article. Teachers may assist in the pre-reading and reading stages by utilizing a K-W-L chart (see Handout 1). For example, what do students know of the leaders and platforms of the Republican and Democratic parties at the time of the Civil War? Students could also be directed to reading appropriate selections from a history text for background information (e.g., events and issues surrounding the causes of the Civil War to appropriate elements of Constitutional powers).

3. Teachers may additionally want to provide comparative copies of historical and contemporary newspapers, political cartoons, letters, and diaries illustrating how different political ideologies have been represented throughout times of similar intensive debate (e.g., debating the causes of war, examining political arguments over domestic issues ranging from energy conservation to educational policy). Appropriate samples and activities relating to the Civil War are found in Illinois History Teacher: Volume 4, Number 2 (1997) issue with the article by Patricia Ann Owens and Paula Seifert, "Lincoln and the Springfield Newspapers during the Civil War," pp. 29-37; Volume 8, Number 2 (2001) "Abraham Lincoln in Illinois History;" and Volume 12, Number 1 (2005) article by Walter Waggoner and Thomas Best, "Copperheads and Pike County in the Civil War," pp. 11-22.

The Ken Burns film series on the Civil War also offers a summary of wartime political conflict in the North in these segments: Episode 1-"The Cause," segment on "Secessionists," has information on the 1860 presidential election; Episode 5-"Universe of Battle," segment on "Bottom Rail on Top," contains a narrative of opposition to the wartime draft; and Episode 7-"Most Hallowed Ground (1864), segment "Summer 1864," offers background on the turmoil surrounding the 1864 presidential election.

Developing the Lesson

1. After reading the narrative section of this article, review the major ideas and concepts by answering the questions in Handout #2.

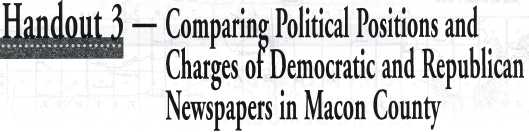

2. Collect samples of editorials from newspapers mentioned in the narrative section of this article: the Democratic-aligned Magnet, Gazette, or Times and the Republican paper, the Chronicle. Create a T-chart to compare allegations and charges lodged at the political positions of each paper. See Handout 3.

3. To challenge the students to think more critically and creatively, ask them to do one of the following activities listed in Handout 4 (e.g., creating a play, writing a letter, drawing a picture, creating a political cartoon, or writing a newspaper editorial):

Concluding the Lesson

1. Teachers who chose to use the K-W-L chart can now ask students to summarize what new ideas they have gained regarding the political environment in Macon County during and after the Civil War.

2. Teachers can display and offer for examination the creative products their

30

students developed ranging from skits to the imaginary newspaper editorials. Ask the students to identify what earlier established key terms and individuals were included in their products. Students should recall what they initially included in the answers to their review questions and T-Chart (Handouts 2 and 3). Were these ideas and samples of political rhetoric and conflict included in their creative efforts?

Extending the Lesson

1. Students can undertake research in their own county or region of Illinois to evaluate the impact of demographics on the political allegiance of citizens. To accomplish this task, teachers should obtain a copy of the census reports from the decades prior to the Civil War to analyze the patterns of settlement of residents from the southern and northern regions of the United States. Newspapers of the era will often print township and countywide voting results. Therefore, students could compare these results in such elections as the presidential elections of 1860 and 1864 with the earlier obtained demographic data from their county. Did those of southern or northern backgrounds vote consistently for specific political affiliations?

2. Some Internet sources offer additional insight into the nature of political conflict in the Civil War. Two excellent Internet sources are "Illinois During the Civil War" http://dig.lib.niu.edu/civilwar and "Abraham Lincoln/Net" http://lincoln.lib.niu.edu Both offer a wealth of primary sources to help examine the thinking of both the ordinary citizen and soldier and the ideology of Abraham Lincoln. There are links on each website to instruction and lesson plans regarding political events and the Civil War (e.g., political speeches, newspaper editorials, video instruction from such experts as John Y. Simon of the Ulysses S. Grant Association, etc.).

3. Students could be further asked to watch contemporary news broadcasts on television, search out partisan websites and blogs, and read newspapers and magazines to examine the nature of political rhetoric in the present day. What style of language marks contemporary political allegations and charges between major political parties, and candidates? What constraints upon freedom of speech or new forms of political ideology do they see as having evolved from the era of the Civil War to the present? Are media commentators more civil in their characterizations of politicians and their parties or do such outlets for news and editorial comment appear equally willing to engage in strong personal attacks? Teachers and students may also create a Venn diagram that compares the extent and nature of political rhetoric expressed in Civil War era newspapers with those of today (e.g., what is the acceptable nature of rhetorical condemnations, words that have the nature of branding another person or party as unpatriotic, etc.).

4. For those who wish to search deeper into the subject of the Civil War newspapers for portions of this lesson, the following sites will be valuable to teachers and students. The well-known illustrated newspaper of the era, Harper's Weekly, is online at: www.sonofthesouth.net/leefoundation/the-civil-war.htm. Illinois Civil War newspapers can be found and examined at: http://dig.lib.niu.edu/cwnewspapers/ The Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library will also be of use: www.illinoishistory.gov/lib/ Finally, the Library of Congress Memory Page has an excellent source for learning how to use primary sources. There is a special activity, "The Matthew Brady Bunch," for writing an article for a Civil War newspaper based upon the use of Civil War photograph http://memory.loc.gov/learn/lessons/98/brady. home.html

Assessing the Lesson

Teachers may create their own rubric to assess the creative products developed by their students. Specific criteria to use in the evaluative process could involve the quantity of factual examples and comparisons; the ability of the student to express his own understanding of the political partisanship through the spoken or written word, or visual representation; and the level of logical connections and reasoning between the historical characters and issues and their own words and visual expressions. An excellent source for evaluating such projects would be the rubrics found in The Alternative Assessment in the Social Studies by Lawrence McBride, Frederick Drake, and Marcel Lewinski.

31

Create a K-W-L chart regarding the topic of what students know about political differences and conflict between the Democratic and Republican Parties during the Civil War.

32

These questions are intended to assist the students in reviewing and thinking critically of the information and interpretation offered in this article.

1. What part did the demographic and cultural origins of Macon County residents play in the shaping of their political allegiances in the era of the Civil War?

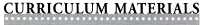

2. By way of speeches and newspaper editorials, how did members of the Republican Party characterize the war-time support of Democratic Party for preserving the Union? What visual images were used to portray their opponents as destructive to the cause of preserving the Union? (e.g., "They are Democratic devils" from the speech by Richard Oglesby on page 23).

3. How did members of the Democratic Party respond to such negative characterizations and criticisms by Republican political leaders and editors?

4. Which of the arguments made by the Republicans or Democrats appear to be better grounded in fact and logic? Which arguments appear to be less valid?

33

5. How did the two parties make use of propaganda to make their arguments (e.g., using emotional appeals to sidestep facts and logic)?

6. In what ways did the political fighting of the Civil War era transcend into verbal and physical conflicts following the war? What did it mean to have a Republican politician wave the "bloody shirt" at Democratic opponents?

7. Compared to the diversity of today's many media outlets, how influential must individual partisan newspaper editors of the 1860s have been in shaping political thought and activities of their readers?

34

Create a T-Chart on the board and/or student papers and collect and compare samples of positions and charges from articles and editorials in the Democratic Party-aligned Magnet, Gazette, or Times vs. the Republican paper, the Chronicle.

| Democratic Papers: |

Republican Papers: |

| Magnet, Gazette, Times |

Chronicle |

| Sample: Shoaff's Magnet argued that to be a Democrat was to be loyal to the Union and that Democrats were willingly fulfilling the ranks of Lincoln's armies. |

Republican papers argued that unless Democrats supported Lincoln to their utmost, they were traitors. | |

35

|