|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

JOHN ALEXANDER LOGAN: DEMOCRAT, GENERAL, AND RADICAL REPUBLICAN  Bruce Tap John Alexander Logan was born on February 9, 1826, at the present-day site of Murphysboro, Illinois. Logan's father, also named John Logan, was an immigrant from Northern Ireland who had originally settled in Maryland. Logan senior lived briefly in Perry County, Missouri before moving to Jackson County, Illinois, in 1824 and marrying Elizabeth Jenkins. Logan senior was a physician by trade, having studied medicine with his father. John Alexander Logan was the first of the couple's ten children. Politics were important to the elder Logan, who was a Democrat and follower of Andrew Jackson. The elder Logan was elected to the Illinois General Assembly in 1836, 1838,1840, and 1846. The involvement of Logan senior in politics was important in understanding the younger Logan's enormous political appetite. The young John or "Jack" Logan had a relatively pleasant childhood. Although Logan's father practiced medicine and politics, he also owned a farm. Logan's childhood was spent performing farm chores, but he also had time and money to devote to hobbies such as horse racing. Initially educated at a school in Brownsville, Logan senior sent John and his brother Thomas to Shiloh Academy in nearby Randolph County. After studying Latin, arithmetic, spelling, and grammar, the Logan brothers returned to Murphysboro in 1845 and were taught by a private tutor. After serving in the Mexican War as a second lieutenant in Company H of the First Illinois volunteers, the twenty-two-year-old Logan returned to Murphysboro in 1848.  36 Deciding on a legal career, he enrolled at the University of Louisville Law School in 1850 and graduated in February 1851. Logan then successfully ran for prosecuting attorney of the Third Judicial District. In order to more effectively perform the duties of his office, Logan moved to the more centrally located Benton, approximately 30 miles northwest of Murphysboro. Shortly after, Logan resigned from his post to focus on a run for the Illinois General Assembly, representing Jackson and Franklin counties. Like his father, Logan was a Democrat and endorsed such typical Democratic beliefs as states' rights and territorial expansion. Additionally, Logan positively disdained the anti-slavery movement, regarding abolitionists as dangerous fanatics who would destroy the fabric of American society. Logan had the skills, looks, and family connections for a successful political career. A gifted orator, he possessed a booming voice that could excite and invigorate his audience. Although not a large man, his long black hair, piercing ebony eyes, and swarthy complexion gave the young attorney an impressive presence (some incorrectly believed that Logan had native-American blood). Since Logan was already well known in the region, it is hardly surprising that he was easily elected to the General Assembly in the election of 1852. Logan's first term in the assembly was associated with the 1853 anti-black laws, sometimes referred to as the Logan Laws. As a native of southern Illinois, or "Egypt" as it was commonly called, Logan was influenced by the racial prejudices of his constituents. Southerners migrating from Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee had primarily populated southern Illinois. Sympathizing with the southern states on slavery, many southern Illinois residents were, at the same time, fiercely negro-phobic, meaning they wanted little or no contact with African-Americans. Accordingly Logan introduced a bill to prohibit the immigration of free blacks into Illinois. The Illinois Constitution of 1848 had provided for anti-black laws; however, it had left it to the legislature to enact them. Logan's bill fined free blacks that migrated into Illinois and imposed a ten-day jail sentence. It was overwhelmingly passed by the General Assembly. Logan soon craved a more prestigious office, and he began positioning himself for the Ninth District U. S. congressional seat. In order to accomplish that, Logan allied himself with the rising star of Illinois politics, Stephen A. Douglas. Already in the Senate for several years, Douglas had grown to prominence for his legislative sponsorship of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, a bill that proposed to solve the growing dispute over the expansion of slavery into federal territories by allowing the inhabitants of the territories to decide the issue for themselves. Logan also formed a politically savvy law partnership when he joined forces with William "Josh" Allen, the son of former southern Illinois Democratic congressman, Willis Allen. On November 27,1855, Logan married seventeen-year old Mary Simmerson Cunningham. The Logans' thirty-one year marriage produced three children: John Cunningham Logan (born in December 1856), Elizabeth Mary (born June, 25,1858, and nicknamed Dollie and Lizzie), and Manning Logan, born on July 24,1858. The eldest Logan child died before reaching his first birthday. In 1858 Logan was nominated as the Democratic candidate for the Ninth District of Congress. His association with Stephen Douglas paid dividends as Logan made a number of joint appearances with Douglas throughout southern Illinois. Douglas's popularity undoubtedly contributed to Logan's easy victory on election day. Beginning his term in Congress in December 1859, Logan received an appointment to the inconsequential committee on Revisal and Unfinished Business. Despite this seemingly unimportant assignment, Logan soon put his stamp on his freshman term when he blasted northern antislavery advocates for refusing to acknowledge the constitutionality of the Fugitive Slave Law. Because Logan recognized the necessity of returning fugitive slaves to their southern masters ("dirty work" as Logan called it), he earned the nickname "Dirty Work" Logan. In 1860 the election of Republican presidential candidate, Abraham Lincoln, led to a constitutional crisis. Worried that Lincoln's election threatened the institution of slavery, South Carolina seceded from the Union in December 1860 and was soon followed by Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. During that critical time, Logan placed most of the blame for sectional crisis on antislavery Republicans and abolitionists. Re-elected to Congress by a sizable majority, Logan urged conciliation and compromise throughout the winter of 1860-1861, and he denounced military force as an acceptable way of meeting the secession crisis. After the firing on Fort Sumter, Logan continued to denounce the use of force. In that regard, he differed markedly from his political 37  mentor, Stephen Douglas. After the firing on Fort Sumter, Douglas vigorously endorsed military force to restore the Union and told an audience in Chicago, "there can be no neutrals in this war, only patriots—or traitors." Logan continued to endorse peaceable compromise and bitterly denounced the position staked out by Douglas and other northern Democratic leaders. Indeed, so strong was Logan's opposition to Douglas's course, that many believed the southern Illinois Democrat would support the Confederacy. There were a number of reasons why Logan struggled to make his eventual decision to support the Union. First, many of his southern Illinois constituents sympathized with the seceded states and wanted to aid the Confederacy. Secondly, Logan's family was predomi-nately pro-southern, as were many of Logan's associates, including law partner Josh Allen. In fact, several mem-bers of Logan's immediate family and his wife's family were so devoted to the cause of the South, they criticized Logan when he eventually backed the war. Although Logan never seriously contemplated supporting the Confederacy, he moved slowly from a position of peaceable compromise to the use of military force to put down the rebellion; consequently, for several weeks after the firing on Fort Sumter, Logan said nothing. As a result, Republican papers attacked him for alleged disloyalty. In the summer of 1861, Logan finally declared his position. In early June, he was in Springfield, where he happened to meet Ulysses Grant, the colonel of the Twenty-First Illinois. Commanding a ninety-day regiment, Grant was eager to persuade its members to re-enlist for three years, lest the unit dissolve by mid-summer. Grant asked well known Democratic congressman, John A. McClemand and Logan to address his regiment. Logan delivered a passionate speech on the necessity of fighting to preserve the Union. There was no longer any doubt about Logan's devotion to the Union. Convinced that he should answer the call to arms, Logan solicited and received a colonel's commission. He then returned to Marion (where he had moved in 1861) where he mesmerized local residents with another spellbinding speech supporting the Union. The speech undoubtedly assisted in raising a southern Illinois regiment, which was mustered into service as the Thirty-First Illinois on September 18, 1861. Logan's regiment was assigned to the brigade of Brigadier General John A. McClemand, but he ultimately reported to then Brigadier General Ulysses Grant. Logan was a political general, but he did not fit the stereotype of a political general. In the popular press and among graduates of the United States Military Academy at West Point, so-called political generals were ridiculed for poor battlefield performance. Nevertheless, with their ability to aid recruiting, create support for the war effort, and their administrative experience, political generals did play a significant role in the war, and the Lincoln administration needed their participation. John A. Logan, however, did not fit this mode. With the exception of his experience in the Mexican War, Logan was a novice on the battlefield. However, by reading manuals on drill and battlefield tactics, eventual combat experience, natural ability, and force of will, Logan became an excellent field commander, whose numerous military successes were recognized by such West Point educated generals as Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman. Logan began his military service in the West, leading his Thirty-First Illinois at the battle of Belmont (Missouri). At the battle of Fort Donelson (Tennessee) on February 15, 38  1862, Logan was wounded three times. Inaccurately reported as dead, Logan was nursed back to health by his wife. Appointed brigadier general in March 1862, Logan returned to Grant's army just after the battle of Shiloh in April 1862 and commanded the first brigade of the Third Division in the Seventeenth Corps. Logan, who was promoted to major general in February 1863, performed admirably in the Vicksburg campaign under Grant. He now commanded the entire Third Division of the Seventeenth Corps. At the battle of Champion Hill (Mississippi), on May 16, 1863, Logan's division played a pivotal role in a successful flank attack on Confederate troops under Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton. Logan's distinguished service again led to promotion, as he was elevated to full corps commander in October 1863. He now commanded the Fifteenth Corps in the Army of the Tennessee.  During the Atlanta campaign in the summer of 1864, Logan again lived up to expectations. At the Georgia battles of Dallas (May 25-28, 1864), Atlanta (July 22, 1864), and Ezra Church (July 28, 1864), Logan's coolness under fire and seeming indifference to danger provided inspiration to the men under his command. They affectionately referred to him as "Black Jack." At the battle of Atlanta, Logan capably directed the entire Army of the Tennessee after its commander, Major General James B. McPherson, was killed. For his efforts, Logan expected William T. Sherman (overall commander in the West) to name him as permanent commander of the Army of the Tennessee. Sherman, however, chose Major General Oliver Otis Howard. While Sherman respected Logan's battlefield actions, he distrusted him because of his political connections as well as his lack of a formal military education. Howard, conversely, was a graduate of West Point. Logan was crushed and correctly suspected that he was denied the appointment because he was not a West Point graduate. Logan would end his military career as commander of the Fifteenth Corps, although he did lead the Army of the Tennessee in the May 24,1865, grand review in Washington, D. C. Logan began the war as a member of the Democratic Party. Like many Democrats, his support for the war was based on restoring the Union and had nothing to do with the abolition of slavery. When the Lincoln administration began to attack the institution of slavery, some northern Democrats grew disillusioned. Led by such Democratic congressmen as Clement Vallandigham of Ohio, significant anti-war movement emerged in the North. These war opponents were known as peace Democrats or Copperheads, and they favored cessation of hostilities and peaceable restoration of the Union with the institution of slavery intact. Logan, however, chose a far different course. When he returned to Illinois on a short leave from the army in August 1862, he hinted at his changing position in a speech delivered at Carbondale. Logan now indicated that he was willing to attack slavery if it saved the Union. By the time of the 1864 presidential election, Logan was a Republican in all but name. Because of his popularity in Illinois, the Lincoln administration desperately needed the popular general to generate support for Lincoln's re-election in Illinois. Since the Democrats had adopted a party platform that denounced the war as a failure, Logan had little trouble campaigning for Lincoln's re-election. Focusing primarily on southern Illinois, Logan gave several speeches in which he denounced peace Democrats and the Democratic platform of 1864 while defending those who supported the war effort. Logan's efforts paid off as Lincoln carried the state of Illinois and even showed a slight majority in 39  traditionally Democratic southern Illinois. When Logan returned to Carbondale (where he had moved his family during the war) in August 1865, he quickly returned to politics. Although during the war Logan had never officially declared his allegiance to the Republican Party, few were surprised when he entered the political realm as a Republican. Logan was elected as Illinois congressman-at-large in 1866,1868, and 1870. Logan did not serve out his last term in the House because the Illinois General Assembly elected him as United States senator in 1871 as a replacement for former Governor Richard Yates. Although defeated for re-election in 1877, Logan was again elected to the Senate in 1879 and 1885. In 1884, he was mentioned as a possible presidential candidate but settled for the vice-presidential nomination on the unsuccessful Republican ticket headed by James G. Blaine of Maine. Ironically, the former Democrat increasingly identified with the radical wing of the Republican Party. The same John Logan who had sponsored anti-black immigration laws in Illinois in 1853, now favored civil rights legislation for African-Americans—including the right to vote. Not only was Logan an eager advocate of President Andrew Johnson's impeachment, Logan served on the committee that drafted impeachment articles and was also one of the seven House managers who presented the impeachment case against Johnson in the Senate in 1868. Logan's popularity in the post-war period was based, in part, on his association with the Grand Army of the Republic. An organization of Union veterans that began in Decatur, Illinois, Logan was elected second grand commander of the group. As grand commander, Logan issued General Order #11 on May 5, 1868, which established May 30 as a date for decorating the graves of soldiers killed in action. This, of course, was the precursor to the national holiday of Memorial Day. Logan's membership in the G. A. R. created a loyal political constituency. It also allowed Logan to use his experience in the Civil War for political advantage. During his last term in the Senate, Logan began writing for publication. His Great Conspiracy, an account of the war and the Reconstruction period, was published within months of his death. The Volunteer Soldier of America was published in 1887. Always jealous of West Point educated soldiers, Volunteer Soldier was Logan's tribute to the contributions of amateur, volunteer soldiers in American history.  Logan was considered a leading candidate for the Republican presidential nomination in 1888. But, tragically, his life was cut short when he became ill in early December 1886, with what doctors diagnosed as rheumatism. By the Christmas holidays, Logan had lapsed into semi-consciousness. He died on December 26, 1886. His death was widely mourned across the country. After his body lay in state at the U. S. Capitol on December 30-31, he was buried on January 1,1887, in Rock Creek cemetery in Washington, D. C. John A. Logan's political career is filled with controversy. Did Logan seriously consider casting his lot with the Confederacy in the spring of 1861 ? Was his post-war conversion to the Republican Party authentic, or was Logan guilty of political expediency? There is little reason to suspect that Logan's decision to fight for the Union was anything but sincere. Like Stephen Douglas, his devotion to the Union was paramount. During the secession crisis, however, events moved too quickly for Logan. Divided sentiments in southern Illinois and his family caused him to hesitate. Once war was inevitable, Logan made the only choice that was consistent with his political principles: he chose the Union. Similarly Logan's transformation from a negrophobic state legislator to a radical Republican who championed the cause of African-Americans was authentic. Logan initially fought only to preserve the Union; however, as the war continued, he realized the need to attack slavery if only to weaken the Confederacy. His military service in the South familiarized him with some of the harsher aspects of slavery and undoubtedly influenced his opposition to slavery on moral as well as practical grounds. Indeed, his postwar advocacy of African-American civil rights suggests that Logan believed that whites and blacks shared a common humanity. Logan's advocacy of equality before the law and his devotion to the plight of African-Americans well into the 1880s provides ample evidence that his political conversion was sincere, making his career one the most remarkable tales of political transformations in United States history. 40  Rivanna Abel John A. Logan and the Personal Side of the Civil War

Main Ideas The Civil War is often viewed as a black and white, North and South battle. It was, however, much more nuanced. The Civil War, especially in the border states, became a personal struggle as politicians, families, and communities had to come to terms with the war—why it was being fought and which side to fight on, and how to reconcile the two ideologies. One of the many ways to study the Civil War is to look at individual soldiers and their personal struggles with the Civil War. Connection with the Curriculum This material may be used to teach United States history and Illinois history. The primary focus of this study is the personal and political life of John A. Logan. These materials may be appropriate for Illinois Learning Standards 14.C.4,14.F.4a, 16.A.4a-b, and 17.A.4b. Teaching Level Materials for Each Student -- Copy of the narrative portion of this article -- Copies of the hand-outs -- United States history textbooks Objectives for Each Student -- Students will recall and analyze the events of Logan's life -- Students will locate those forums in which Logan participated in the Civil War -- Students will identify the battles that connected Illinois to the Civil War

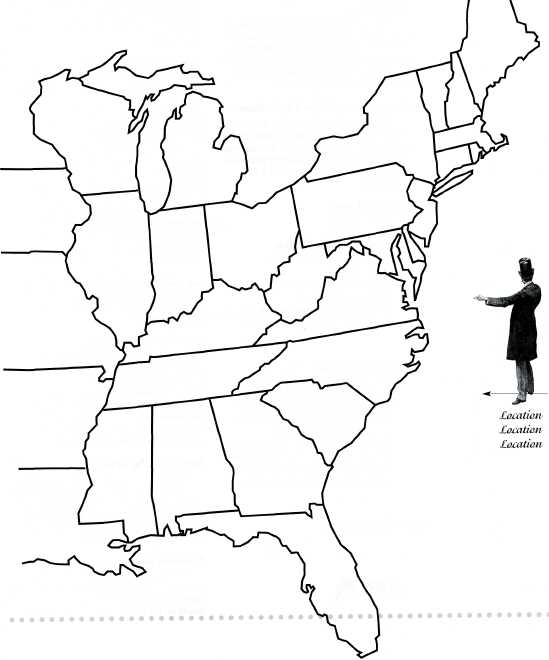

Opening the Lesson Ask students to generate a list of significant Civil War happenings in Illinois. The list can include people and places within Illinois that were training grounds, battle sites, etc. Then, discuss with the students the attitudes of Illinoisans toward the Civil War. Was the state entirely Union? Was it Confederate? Include the idea of Copperheads and why southern Illinois in particular was a contentious site during this time. Developing the Lesson In Activity 1 the students will read the narrative article and answer the recall and analysis questions. Concluding the Lesson Activity 1 is to be graded individually. Activity 2 can be graded individually, or it can be discussed as a class and the students can participate in a group activity to locate the battle sites on an overhead or larger map. Once the activities have been collected, a discussion of the importance of Illinois in the Civil War can review the reading. Extending the Lesson Students can choose other generals from other border states to research. For a comparison to Logan and to the struggle that was carried out in Illinois, students can further research Southern generals and the ways in which Southern, pro-states' rights states faced similar problems to those in the border states. Assessing the Lesson Activity 1 is to be evaluated on its accurateness of recall information. Analysis questions should be measured for their comparative qualities. The map can be taken as a completion grade, or it can be evaluated for its specific locations. Discussions can be evaluated through a summative essay or short answer quiz. 41  1. Where and when was John A. Logan born? 2. What did Logan's father do for a living, and how was he trained in his profession? 3. Describe the education of Logan. What formal education did he receive, and what education did he get from his hobbies and home? 4. Define negrophobic. Was Logan negrophobic? 5. List the provisions of the 1853 Black Laws. 6. In 2 to 3 sentences, summarize Logan's political career during the 1850s. 7. Who did Logan beat in the 1858 election, and why was this significant to Illinois politics? 8. List the political parties in the 1860 election, and the stances of each. 9. Compare the political commitments of Logan to his mentor Douglas. 10. How did Logan go from negrophobe to supporter of the Civil War? 11. What is the other name for the Battle of Manassas? 12. Why were political generals necessary for the recruiting process? 13. Why was Logan such a good general? 14. Define Copperheads. 15. How did Logan manage to support the Emancipation Proclamation when he hated abolitionism? 16. What kind of system did Logan support when he wanted political jobs to go to loyal party members? 17. Define political expediency. Do you think Logan was guilty of this? 42  Locate the battles in which John A. Logan was involved in the Civil War.

43  The Civil War As Seen Through the Experience of John A. Logan

Main Ideas The Civil War was fought for a variety of reasons including economic issues, slavery, and states' rights. By looking at the life and career of John A Logan, students can examine how those themes intertwined to make the Civil War since a complex issue. Connection with the Curriculum This material may be used to teach United States history, Illinois history, or United States government. The narrative and activities may be appropriate for Illinois Learning Standards 14.A.5, 14.D.4, 14.F.4b, 14.F.5, 16.A.5a, and 16.B.5a. Teaching Level Grades 10-12 Materials for Each Student -- Copy of the narrative portion of the article -- Copy of activity hand-out -- Access to the Internet -- Presentation materials: posters, overheads, Power Point, board, etc Objectives for Each Student -- Students will recall, analyze and evaluate the life of John A. Logan -- Students will research current United States congresspersons with terms of service exceeding two terms -- Students will analyze political change as it occurs over the course of a single person's career, and make conclusions about why such changes take place  Opening the Lesson Prompt students to brainstorm a list of high-profile politicians. Broaden this to include the stances, or at least the parties, of each politician. Discuss why these politicians are high profile. Developing the Lesson  Using Activity 1, have the students read the narrative and answer the accompanying questions. Discuss the questions once the students have finished the assignment, with emphasis on Logan's political change over the course of his lifetime. For Activity 2, divide students into pairs. Assign each pair one of the politicians that was listed on the board earlier. Students can also, briefly, research United States congresspersons and choose one of their own. Congresspersons should have served at least two terms. Allow the pairs to research their Congresspeople via the internet or other available resources over the course of 1 or 2 class periods. Each pair must present on the following for the Congressperson: background and education; political life as a child or early adult; political party and stances within that platform; and votes on major issues over the past five years. Concluding the Lesson Once the students have finished their presentations, discuss how the politics of Congresspersons change over time. Brainstorm reasons for such changes, and the impact that Congresspersons, especially high profile ones, have on party platform. Discussion of the public perceptions of legislators would also be appropriate. Extending the Lesson Bringing in a local politician (a councilper-son or state representative) would be an excellent way for the students to discuss their ideas with someone who has a different viewpoint from their own, and who could possibly explain how and why such political changes occur. Assessing the Lesson Activity 1 is graded individually once completed. Group presentations are graded using a rubric at the teacher's discretion (based on the presentation format preferred). 44  In 4 to 5 sentences, summarize each of the following: Logan's Youth, Education, and Family

Logan and Politics: Upbringing, Training, and Service Logan, Negrophoia, and the 1853 Anti-Black Codes Logan, Lincoln, the Crittenden Compromise, and Support for the Civil War Analyzing the statement: "There can be no neutrals in this war, only patriots— or traitors," discuss Logan's involvement in the Civil War Political Transformation from "Dirty Work" Logan to "Black Jack"

John A. Logan and the Black Codes

Main Ideas It is sometimes difficult for students to grasp how a northern state such as Illinois could be as racially discriminating as those states of the South. Northern "black codes" and other similar legislation is often forgotten in the pre-Civil War and Reconstruction eras simply because of the amount of other material to cover. However, studying the existence of such legislation and the accompanying social and cultural atmosphere makes studying later historical events (e. g., the civil rights movement, affirmative action) all the more relevant, and helps to explain the ongoing racial tension that is seen in the United States today. Connection with the Curriculum This lesson can be used to teach United States and Illinois history, and United States government. The lesson may be appropriate for Illinois Learning Standards 14.A.4-5, 14.F.4a-b, 14.F.5, 15A5c, 15.C.4a, 15.E.4a, 15.E.5b, and16.B.5b. Teaching Level Grades 10-12 Materials for Each Student -- Copy of narrative portion of the article -- Copy of supplemental readings from the following Web sites: www.slavenorth.com/exclusion.htm http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Codes Objectives for Each Student -- Students will analyze why Logan and other politicians during the Civil War era supported such legislation as the black codes -- Students will discuss the impact that such codes had on society socially, economically and politically -- Students will assess how these codes impacted Illinois as a "border state" 46  Opening the Lesson Begin the lesson with a brief discussion of how the North and South differed in their views toward blacks during the Civil War era. Discuss the social hierarchy of the North compared to that of the South, and the different reasons for each social structure. This discussion could include abolitionism and religious differences as well as social and economic variances. Developing the Lesson Have the students read the narrative portion of the article, paying close attention to the atmosphere of Illinois, the type of legislation that Logan supported and opposed, and why the atmosphere of Illinois was so contentious during Logan's lifetime. Students should be encouraged to make notes on their copies of the narrative. Once the students have completed the reading, have them brainstorm the main points of the 1853 Illinois black codes on the board. Include why the black codes were implemented and why Logan supported the legislation. Move the students on to the supplemental readings. These readings should be divided among the students so that each student has one reading or section in order to keep the lesson moving quickly. Add additional information from these readings to the list on the board. Concluding the Lesson At the end of the lesson, divide the students into small groups to discuss the different reasons for black codes, and what Illinois gained economically, socially, and politically from passing this legislation. The small groups should create a conclusive statement about how the black codes influenced Illinois as a "border state." Extending the Lesson One possibility would be to have the small groups do further research on black codes in different states to compare to the codes passed in Illinois. The students could present the information they gathered, or regroup in a jigsaw fashion to share their new information with all of their classmates. An alternative possibility would be to compare the black codes passed in the United States during the nineteenth century with those racially restrictive codes passed elsewhere in the world at the same time period: the beginnings of apartheid in South Africa, the Mestizo laws of Latin and South America, etc. Assessing the Lesson Assessment should be based on how well, in written or oral form, the students are able to express the information they received from the readings and discussions. Teachers should create their own evaluative essay questions or presentation rubric based on the classroom discussion. The lesson could also be evaluated as part of a larger unit dealing with the Civil War as a whole, and incorporated into a unit test utilizing both multiple choice and short answer questions. 47 |Home|

|Search|

|Back to Periodicals Available|

|Table of Contents|

|Back to Illinois History Teacher 2007|

|