|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

James E. Davis Clashes between Yankees and Southerners in frontier Illinois began as early as the 1790s and continue in various ways to the present. The clashes originated largely in daily cultural differences, but after approximately 1850, they also sprang from flaring moral and social issues, including slavery and efforts to address or defend it. Despite their deep cultural origins and their occasional severity, most clashes dissipated peacefully by the late-1850s, dying out with the fading of the frontier in Illinois. In 1763 the Treaty of Paris ended the Seven Years War, and it transferred from France to Great Britain all of its possessions in continental North America. Compared to the population in the British colonies, the French population in North America was minuscule. By 1763 French residents and their slaves in present-day Illinois totaled perhaps twenty-five hundred. Virtually all lived along the region's rivers, the majority living in or near Cahokia, Kaskaskia (on the left bank of the Mississippi River), and Vincennes (on the left bank of the Wabash River). Some French during the 1760s fled across the Mississippi River to newly founded St. Louis. Although Britain finally managed to project power into Illinois in late 1766, its control over the trans-Appalachian west was weak. Less than ten years later the American Revolution erupted, and in 1777 the State of Virginia outfitted a force commanded by George Rogers Clark, which in 1778 seized British possessions in the Illinois Country. Tenuous American control provided a basis for American claims to the region. In signing the Treaty of Paris in 1783, Great Britain agreed to independence for the United States. The treaty stipulated the boundaries of the new country, generously giving to the United States vast and thinly populated lands beyond the Appalachian Mountains.

Nearly all of George Roger Clark's force consisted of Virginians and others from the Upper South. Some stayed in Illinois after the war, and others from the South crossed the Ohio River to settle in Illinois. By the time of statehood in 1818, well over 80 percent of Illinois' population had southern roots, the rest hailing from other states and from Europe and Canada. 11

Southerners settled in Illinois for various reasons. Foremost was the desire to better themselves. Some Southerners opposed slavery for moral reasons and wanted to settle north of the Ohio River, where the Northwest Ordinance had put slavery on the road to extinction. Others opposed slavery for the baneful effects it had on non-slaveholding whites in the South, and they wanted to settle where slavery would not flourish. Still others favored slavery, some bringing slaves into Illinois or hoping to do so. Southerners controlled early Illinois. They occupied most political offices, controlled the new state's economy, and set the tone for society, although the shrinking French population retained some influence into the 1800s. After statehood in 1818, the percentage of Yankees grew. The hearth of Yankee culture was in coastal New England, along the rivers there, and in those portions of central New York and northeastern Ohio settled by Yankees. Relationships between Yankees and Southerners dominate much of Illinois' early history, and they often reflect larger forces operating across the country. Those relationships often involved differing assumptions and world views, cultural struggles, much tension, sporadic violence, and even an occasional death. Some clashes sprang from differing world views, broad cultural disagreements, and spats on every-day issues, and sometimes they sprang from specific controversies. Although some Southerners were commercially oriented, most valued a Jeffersonian yeoman model of society. At the core of this model stood small, largely self-sustaining farmers, men who owed nothing and who therefore could act independently. Such sturdy farmers feared the accumulation of political power in distant centers, fretted over the creation of commerce and industry, feared cities, and looked askance at modernity. They valued rural traditions and life, suspected grand plans to reform humanity, and usually viewed the world as a place of sin and sorrow. They stressed negative freedom, including the right to be left alone. This model may be largely Celtic in origin, reflecting people living in relative isolation. In significant ways Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson, and Stephen A. Douglas typified it. This model was opposed by a world view championed by Yankees and others. It supported modernity, urban life, commerce and industry, social complexity, and reforms. It favored the concentration and use of great political power. It generally reflected an increasingly sunny, optimistic view of humanity and the world. It valued positive freedom— the freedom to make claims on the resources of the larger society and reshape it. This model reflected an Anglo-Dutch world view, carried by arteries of transportation. Such men as Alexander Hamilton, Henry Clay, and Abraham Lincoln adopted it. Although Southerners in Illinois and elsewhere valued the ideal of relative self-sufficiency, they sought markets for products and purchased goods from afar. They used rivers and overland trails in connecting themselves to the outside world, and the towns with which they had contact

were almost always on rivers. In significant ways, Southerners in Illinois oriented themselves in a north-south direction along the Mississippi

12

arteries of communication as Great Lakes shipping, the Erie Canal and the Illinois & Michigan Canal, and railroads and the telegraph, all of which linked Illinois to New York City and other Eastern cities. Clearly, the economy of Illinois by 1860 was vastly different from the economy at the time of statehood in 1818. It increasingly reflected the era's new technology and the surging east-west ties to the East Coast. Many broad cultural issues divided Yankees and Southerners. At the risk of overgeneralization, some broad distinctions between Southern ways of life and Yankee ways of life illuminate struggles that flared up in Illinois between the two cultures from the time of statehood through the Civil War and to the present day. Southerners favored common sense and revealed truths, worrying about Yankee emphasis on formal education and the use of cold reason. Southerners thought of themselves as chivalrous and spontaneous, regarding the Yankees as bourgeois and calculating. Southerners enjoyed a relaxed work ethic, which both amused and miffed Yankees, who sported a finely tuned work ethic, one that never seemed to rest. Southerners engaged in the art of storytelling and the deliberate creation of myths, while Yankees touted written histories and formal tradition. Southerners accused clever Yankees of inflicting shrewd business deals on them, and Yankees thought Southerners were shiftless and unmotivated. In significant ways Southerners were romantics, Yankees more pragmatic and formalistic. Southerners leaned toward idealized medieval visions offered by Sir Walter Scott, but Yankees plunged ahead with increasingly rampant capitalism. Many Southerners cherished real or imagined links to England's rural aristocracy and cavalier spirit, often disparaging the growth of cities, commerce, and industry in the North and in England. Southerners liked to think their society, including slavery, was organic and free from threatening divisions, but Northerners worried about incipient class and religious strife.

Southerners stressed face-to-face relationships, condemning in the process what they believed were calculating and impersonal Yankee ways. Southerners bristled at unfair treatment, especially at the hands of the educated and the connected, while Yankees boasted of their sharp commercial dealings. Ideas concerning women's roles differed, Southerners often lifting women to safe and private pedestals and Yankees seeing women as cultural partners and favoring women's involvement in certain public spheres. Southerners boasted of their word, family name, and sense of honor, many sealing deals with a handshake and seeing no need for legalistic Yankee-style written contracts. Kinship and individualism marked many Southerners, while community and covenanted common action marked Yankee thought. Southerners tended to emphasize the private in life, Yankees stressing public roles and the good of the Commonwealth. Missions to vastly improve society raised Southern suspicions, but Yankees took to missions to reform or uplift society. Southerners were quick to take offense, especially over matters of honor, and prone to become visceral and even violent, with Yankees staying unruffled and collected. Spirited and spontaneous religious services by preachers brimming with emotion appealed to Southerners, not to Yankees. Yankees wanted ministers to deliver calmly read and well-reasoned sermons. When Southerners saw organized groups and solid institutions, they worried about conspiracies by the well-connected, while Yankees frequently formed and joined societies and institutions. Followers of Andrew Jackson dreaded conspiracies hatched by hidden powerful interests, a dread shared by anxious Southerners in Illinois. Individual or kin-based effort for private gain marked Southern efforts, while common effort for alleged noble purposes appealed to Yankees. A sense of mission and a desire to reform rarely took root among Southerners, the temperance movement being something of an exception, but mission and desire to reform motivated Yankees. Although many Southerners initially favored abolition, they did so with the intention of colonizing the freed slaves in Africa or in the Caribbean. Yankees moved quickly to abolish slavery in New England and New York and elsewhere, and many were willing to have blacks live among them. Southerners sometimes listened to private admonishments and advice, while 13

Northerners more eagerly proffered public censure and correction. Finally, Southerners worried that their ways of life were under siege by forces of modernity, including those of abolitionism and industrialism, while Yankees in New England and elsewhere worried about Roman Catholicism, disorder, and flagrant barbarism. Southerners feared that the future was eclipsing their civilization, and many Yankees hoped this fear had merit. Perhaps the above paragraphs provide much to ponder. The dichotomies offer contrasting ways that the two sections of the country viewed themselves and each other. These contrasting views played themselves out in Illinois, especially in central Illinois, where Yankee prongs of settlement met Southern settlers settling along the rivers. These contending views and forces grappled with such dichotomies, but they also disagreed over more mundane matters. For example, Southerners relied on pork on almost a daily basis, a fact that prompted many Yankees to look down their noses at them. Southerners liked yellow cornbread and biscuits, freshly baked early in the morning. Yankees preferred wheat bread. Perhaps Southerners were slow to adopt the cook stove, which tended to make them look backward to Yankees. Southern speech patterns amused Yankees, which miffed Southerners. Southerners spoke slowly, often with a drawl or a twang, and they pronounced some words differently than did Yankees. Southerners felt patronized when Yankees found their accents amusing. Southerners even called some objects by names that were different from how Yankees referred to them. Southerners offended Yankees by incessant chewing of tobacco and, worse, Southern women became objects of Yankee derision by smoking pipes. Southerners liked to race horses on circular tracks, but Yankees (when they did not object to horse racing) raced horses on oval tracks. Southerners wore broadbrim hats, which some Northern gentlemen thought made them look debased. Southerners were often intensely religious, but they also often broke the Sabbath, which angered Sabbath-keeping Yankees. Southerners' mustaches offended some Yankees, who generally either wore beards or were clean shaven. Southern men liked to engage in roughhouse activities, including fighting and wrestling, facts that bothered many Yankees. Southern neighbors often kept informal records of social obligations and reciprocity, while Yankees often kept written records of such debts, which did not sit well with Southerners. In general, in everyday life Southerners harbored suspicions that Yankees either made fun of them or regarded them as socially inferior. Some issues flared up that pitted Southerners against Yankees. For example, the fight from 1822 to 1824 over the idea of revising the state constitution to permit outright slavery in Illinois produced tension, some riotous actions, and even some threats. The state was overwhelmingly Southern in its origins. Of great importance in understanding the times, however, is that the effort to permit slavery in Illinois was defeated in a popular referendum in August 1824. Southerners in Illinois did not favor slavery, but they were tired of Yankee attempts to abolish it. In the end, continued Yankee efforts to abolish slavery triggered among many Illinoisans a reaction, causing many people to be vehemently against slavery and, at the same time, against abolitionists. This is central to our understanding of Southern/Yankee tensions in the decades before the Civil War. Political contests after the formation of the Second Party System in the early 1830s were heated affairs. (The Second Party System refers to the rivalry between the Whigs and Jacksonian Democrats and succeeded the First Party System formed in the mid-1790s between the Federalists and the Jeffersonian Democrats.) With virtually all adult white males enjoying suffrage by 1836, politicians stirred up passions and promised much to get votes. Issues pertaining to slavery and race often influenced elections in Illinois, often pitting Southerner against Yankee on specific issues. 14

improvements, believing they would ultimately benefit all of society, even if some benefited more than others for a while. Most Yankees, however, thought that if the federal government could not sponsor a bank and internal improvements, then the state government should sponsor them. By the late 1840s most of these issues were dying down, and passions in the state were cooling. The Mexican War in 1846, however, set the stage for renewed clashes. Abraham Lincoln's muted stand against the war reflected an attitude quite different from the views of most Illinoisans. Fortunately, the real fighting in the war lasted just about a year, and peace was concluded in early 1848. Territorial gains from Mexico, however, ignited new spats. The United States gained the Southwest, including California, from Mexico. As the peace treaty was being hammered out, gold was discovered in California. By 1850 California was ready for statehood. Moreover, some action had to be taken concerning government for the Southwest and a permanent border for the state of Texas. Finally, the slave issue posed two national problems. One involved the buying and selling of slaves in Washington, D. C., the national capital, and the other involved the right of slave owners to recover runaways, slaves who were trying to go North to freedom. Southerners wanted a tough fugitive slave law and they wanted it enforced. After months of stressful labor, the Compromise of 1850 was devised to deal with all of these issues. To many Yankees and others in Illinois, one of the most odious provisions in the Compromise of 1850 was the Fugitive Slave Law. Even to people who had no quarrel with slavery, the unjust provisions of the law and the unjust manner in which it was enforced were obvious and outrageous. This law and attempts to enforce it sparked tensions, threats of violence, and violence. Inflaming public sentiment even more, in May 1854 the Kansas-Nebraska Act, promoted by Stephen A. Douglas and opposed by Abraham Lincoln, addressed the issue of slavery, and in doing so, it generated more vitriolic speech throughout Illinois and the nation and then, by 1856, virtual civil war in Kansas. Adding fuel to the fire were nativist activities in the mid-1850s, a great economic downturn in 1857, the infamous Dred Scott decision in 1857— which threatened to open up the entire nation to slavery—and the destruction of the Whig Party and stresses and strains on the Democratic Party. To a great extent, the Republican Party emerged from the wreckage of the Whig Party by 1856 and from Democrats who could no longer remain Democrats. In 1856 this new party came remarkably close to electing its first presidential nominee, John C. Frémont. The swirl of issues relating to slavery in the 1850s reignited many earlier passions. Illinoisans of Southern background felt put upon. Abolitionists and their allies believed they were on a moral crusade, doing the work of God. As inflamed as feelings became, however, a central fact remains true in Illinois: in nearly every instance differences were worked out without deadly violence. When violence occurred, especially if someone got hurt, the shocked reaction to the violence was such that it clearly indicated that people were not accustomed to such violence and were not going to put up with it. Rather than resorting to violence, the vast majority of those who engaged in these cultural struggles did so within

Yankees, Southerners, immigrants, blacks, Indians, and the dwindling French population in Illinois were in conflict over issues large and small, and inflamed rhetoric quickened passions and stirred many to strident action, action often motivated by feelings of righteous wrath. Despite the significance of the issues and despite flaming language, virtually all Illinoisans restrained themselves and refrained from lethal violence. The violence that scorched Kansas in 1856 and the Civil War that plunged the nation into its largest war spared Illinois direct destruction. By 1861 Illinois, the nation's fourth largest state, had largely resolved quarrels and issues within its borders with minimal violence, and now it turned to sending a quarter of a million soldiers into the Union army under the leadership of Abraham Lincoln. Ironically, so much of the Yankee agenda, including the use of power to usher in modernity, was accomplished by the national government during the presidency of Abraham Lincoln. 15

Overview Main Ideas After the American Revolution ended, many people started to move to the territory between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River. Illinois would be a part of this development. Those who settled in Illinois at this time were for the most part from areas that were considered Southern or had Southern values. As Illinois continued to develop, more people moved from the states in the North or Northeast. Their value Connection with the Curriculum This material would be useful in United States history for the study of the development of the Midwest before the Civil War. It would also be useful for a study of the cultural, political, and economic history of Illinois during the 1800s. Teaching Level Grades 7-12. The material may be appropriate to Illinois Learning Standards 16A.3b, 16A.4b, 16B.Sc, 16B.4, 16C.3b, 16C.4b, 16D.3a, 16D.4a. Materials for Each Student

Objectives for Each Student

Opening the Lesson Before using the activities, briefly explain the early settlement of the Illinois territory and the road to statehood. Also, look at information about the laws made after the American Revolution that would have an impact on Illinois, such as the Northwest Ordinance. Have students read the article and any other information that maybe pertinent to the topic. Spend some time clarifying and defining terms in the article that may be difficult for students to understand. Assign the activities that you feel are the most appropriate for your students. Developing the Lesson The activities for this lesson should help the student gain an understanding of the cultural, political and economic differences between the Yankees and Southerners who settled Illinois. Activity 1: Develop a "T" Chart to help students identify the differences between the Yankees and Southerners in Illinois throughout the first half of the 1800s. This will help the students understand the economic, political, and cultural differences that are highlighted in the article. The chart will provide the basis for writing about the two groups in the fourth activity. This activity could be done individually, but would be a very good cooperative group activity. Each of the characteristics (cultural, political, and economic) could be divided among your groups, or expert groups could be formed to make one of the charts and share information with the base group. 16 Activity 2: The role-play should help students gain a deeper understanding of the characteristics of the two groups in Illinois. Try to get the students to put themselves into the time period. The role-plays should be designed to cover the political, economic, and cultural views. This activity could take two class periods. The first period would be used to organize the groups, develop understanding of the activity and to allow the groups time to write notes for the role play. The second-class period would be used for the role plays. Each group could use 5-7 minutes for the role-play and a little time for class discussion. Activity 3: Analyzing the political cartoon should help students become more aware of the political situation at the time the Compromise of 1850 was passed. Students could do the analysis in cooperative groups or as an individual activity. Activity 4: This is a writing activity based on the information taken from the article. The "T" Chart activity would help students with facts for their essays. The writing assignment should be adjusted to take in consideration the writing abilities of the students. Concluding the Lesson Each of the activities could be used as a lesson activity. You might have a class discussion, or small groups might share the main ideas in each lesson. It would be good to connect the student work to the objectives of the lesson.

Extending the Lesson

Assessing the Lesson To evaluate the writing and the role-play you could use or adapt the 4-points on rubric www.isbe.net located in the Learning Standards area under "social science assessments". The rubric has dimensions of knowledge, reasoning, and communication that can be modified to align with the student work. 17

Use the information from the article for this activity. Have students make "T" charts showing the differences between Yankees and Southerners in Illinois. Students put the characteristic at the top (cultural, economic, or political) of the page. Make a two-column chart by drawing a line down the middle of the page and a line across the top. On top of the left column put the word Yankees and on the top of the right column put the word Southerners. Three different charts will be made showing the political, economic, and cultural differences between the two groups. See the example below.  18

Have students put themselves into the time period 1830-1855 as a resident of Illinois. Establish five groups of students, with each group given a topic for a role-play. Have students use the concepts and information they learned from the previous activities, the article, and their own research as part of their role-play. Group 1: Role-play a group of people (family, friends talking, people on the street, etc.) discussing or acting upon their Yankee culture and traditions. Topics could include family life, value systems, and traditions. Group 2: Role-play a group of people discussing or acting upon their Southern culture and tradition. Topics could include family life, value systems, and traditions. Group 3: Role-play a group of people discussing the political situation from a Yankee point of view. (Groups could be people on the street, a group of legislators or relatives talking.) Topics could include issues involving slavery, the Black Hawk War, land for railroads or canals, etc. Group 4: Role-play a group of people discussing the political situation from a Southern point of view. Topics could include issues involving slavery, the Black Hawk War, land for railroads or canals, etc.

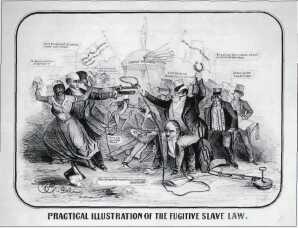

Group 5: Role-play a group of people discussing their economic situation around 1850 in Illinois. The views of both Yankees and Southerners should be part of the role-play. Topics could include the job related items, building of a new railroad, and progress made in rural and city areas. 19 Activity 3 —Analyze a Political Cartoon Students should review the main points of the Compromise of 1850. Have students analyze the political cartoon about the Compromise of 1850. Then students should answer the questions about the cartoon using information they have learned from the article and other resources. 1. How would a Southerner in Illinois react to this cartoon? 2. How would a Yankee in Illinois react to this cartoon? 3. What would be the reaction to this cartoon in New England? 4. How might a plantation owner in South Carolina react to this cartoon? 5. What would Stephen Douglas and Abraham Lincoln say about this cartoon? 20

Explanation of "Practical Illustration of the Fugitive Slave Law" This cartoon is a satire on the antagonism between Northern abolitionists on the one hand, and Secretary of State Daniel Webster and other supporters of enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Here abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison (left) holds a slave woman in one arm and points a pistol toward a burly slave catcher mounted on the back of Daniel Webster. The slave catcher, wielding a noose and manacles, is expensively dressed and may represent the federal marshals or commissioners authorized by the act (and paid) to apprehend and return fugitive slaves to their owners. Behind Garrison, a black man also aims a pistol toward the group on the right, while another seizes a cowering slaveholder by the hair and is about to whip him saying, "It's my turn now Old Slave Driver." Garrison: "Don't be alarmed Susanna, you're safe enough." Slave catcher: "Don't back out Webster, if you do we're ruined." Webster, holding "Constitution": "This, though Constitutional, is "extremely disagreeable." Man holding volumes "Law & Gospel": "We will give these fellows a touch of South Carolina." Man with quill and ledger: "I goes in for Law & Order." A fallen slaveholder: "This is all your fault Webster." In the background is a Temple of Liberty flying two flags, one reading "A day, an hour, of virtuous Liberty, is worth an age of Servitude" and the other, "All men are born free & equal." The print may (as Weitenkampf suggests) be the work of New York artist Edward Williams Clay. The signature, the expressive animation of the figures, and especially the political viewpoint are, however, uncharacteristic of Clay. (Compare for instance that artist's "What's Sauce for the Goose," no. 1851-5.) It is more likely that the print was produced in Boston, a center of bitter opposition to the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850 and 1851. Harpers Weekly 21

After creating the three "T" Charts, have students write a paper (at least five paragraphs) that will analyze the differences between the Yankees and Southerners in Illinois. Students should write at least one paragraph about each of the charts, (political, economic, cultural). High school students could write a longer essay giving more detail about the political, cultural, and economic characteristics of the two groups.

Some questions to consider when writing your paper: 1. What are possible reasons for Yankee and Southern culture and traditions found in Illinois in the 1800s? 2. How did Southerners and Yankees view the world? 3. How would Yankees and Southerners view future development in Illinois and in new territories? 22 |

|

|