|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

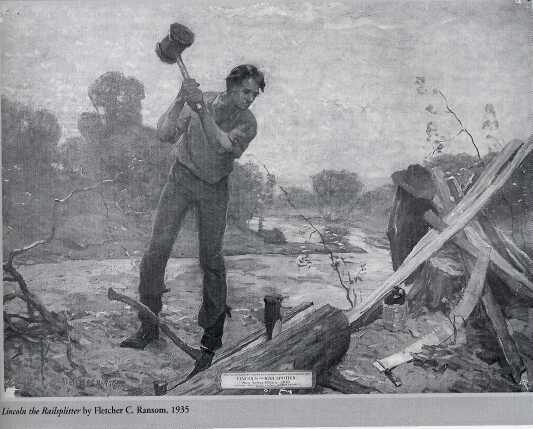

1 • 8 • 3 • 1 — 1 • 8 • 3 • 6 Lincoln's Formative Years at New Salem Kenneth J. Winkle Beyond his extraordinary qualities as a national leader, in many ways Abraham Lincoln exemplified the pioneers who settled Illinois and made it one of the most agriculturally productive and politically important states by the time of the Civil War. A native Kentuckian, Lincoln spent most of his youth working with his family on the farming frontier that moved through the Old Northwest during the 1820s and 1830s. He took full advantage of the social and economic opportunities that were becoming available in the free society of the North and, above all, worked diligently to improve himself. Living in the small rural village of New Salem as a young adult, he experimented with a variety of occupations before settling on a life of public service through a career in law and politics. His six, formative years at New Salem (1831-1836) helped prepare him to thrive in the industrialize, urbanizing nation that was emerging and, eventually, become its leader. Above all, he embraced the values of equality, opportunity, and improvement that underlay this free society and committed himself and eventually the nation to extending these essential ingredients of freedom to all Americans. The Farming Frontier Until the War of 1812, the Shawnee, Kickapoo, and Sac and Fox Indian tribes dominated the Illinois Country, and the British occupied forts along the Great Lakes. After the war, the British withdrew, the U.S. claimed more of the Indians' land, and American armers began to move westward. Between 1815 and 1830, six new western states entered the Union in only five years, including Illinois in 1818. Southern settlers from Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee dominated the early Illinois frontier. They tended to travel to Illinois along water routes moving northward along the Mississippi, Wabash, and Illinois rivers and planting farms and new towns on the way. As a result, initial settlement in Illinois formed a frontier line that followed these rivers and moved slowly from south to north. The Lincoln family came to Illinois to settle on this prairie farming frontier in 1830. Abraham Lincoln was born into a farming family in Kentucky in 1809. When he was seven, his father Thomas decided to move his family north of the Ohio River to Indiana. The move was one of the most important events in Abraham Lincoln's life. In later years, he cited a growing disillusionment with slavery and a controversy over land titles as his family's main reasons for leaving Kentucky. Because of an archaic system of recordkeeping in Kentucky land claims "shingled," or overlapped like shingles on a cabin roof. As a result almost one-half of Kentucky's pioneers lost their land through faulty titles. Thomas Lincoln lost his first two farms in that way and faced the loss of his third farm, as well. The United States government was selling land in the Old Northwest for $2 an acre and securing all titles according to the Congressional Survey In March 1830, when Lincoln was twenty-one the family moved westward again to Illinois. They settled near Decatur on the Sangamon River, where they encountered Illinois' famed prairies and practiced prairie agriculture for the first time. Traditionary southerners preferred to farm dense woodland, which they considered more fertile than prairie land, and typically spent years clearing trees from the forests to make fields. Abraham Lincoln, for example, spent most of his boyhood between ages seven and twenty-one cutting down trees. Now, as the Lincolns moved out onto the prairies of Illinois, he exchanged his ax for a hoe and "broke prairie," laboriously 2

peeling off the thick sod to reveal the rich, black soil beneath. In their first year, he and his family broke ten acres of ground and planted it in corn. Like the other pioneer families of Illinois, they discovered that the prairies were even more fertile than the woodlands. Before long, settlers preferred the prairies, realizing that they could make a farm "by merely fencing it in and ploughing-no chopping-no logging-no stumps." Farmers began pouring into central Illinois. When the Lincolns arrived in 1830, Sangamon County was already the most populous county in the state, boasting thirteen thousand settlers, four-fifths of them farmers. Pioneer Families Until the advent of railroads in the 1840s, transportation was slow and expensive. Farmers had trouble marketing their produce, and manufactured goods were expensive and hard to come by. Farmers had no choice but to engage in a sophisticated system of home manufacturing. Before the advent of factories and the appearance of reliable and efficient transportation systems, Americans met most of their needs through family-based production within a system that historians call the "family economy." In a largely subsistence economy like that on the

Illinois frontier, families worked mostly to meet their own immediate needs rather than producing goods for sale on the market. Farm families produced a wide variety of products rather than specializing in one or a few staple, cash crops. Most important, of course, were foods for the On the prairie farming frontier, families produced many manufactured goods themselves, bartered with neighboring families, and patronized craftsmen for manufactured goods. This family economy depended on neighborly relations, because one lesson of the prairie, 3

according to an old settler, was simply that "one family could not live alone." Within families, husbands and wives observed tradition in practicing a gendered division of labor. Men and boys worked outside—in the fields and forests, tending crops, hunting game, and chopping wood. Women and girls usually worked inside or near the house, performing a vital economic function by manufacturing items for home consumption such as clothing, soap, and candles. Spinning, weaving, and cloth production in general were the most important occupations of women and girls. The work of growing cotton or raising sheep, picking cotton seeds from the fiber, carding and spinning it into thread, and weaving it into cloth was as vital to family survival as all the farm work in the fields. This "women's work," like all farm work, was seasonal. Farmers planted cotton and flax in the spring, and in the summer the cotton had to be picked and seeded and the flax fulled. Farm wives and daughters spent the fall and winter spinning and weaving cotton fiber and flax to provide cool clothing for the summer ahead. In the spring, just as the cotton and linen clothing was ready, the men washed and sheared the sheep and turned over the raw wool to the women and girls, who spent the spring and summer spinning, weaving, and dyeing wool in time for winter. Cloth production was hard work, and few women remembered it fondly, but it afforded frontier families an important measure of economic independence. And it granted female family members, in particular, a vital economic function. Families also made their own soap, candles, butter, sugar, and leather goods, processing a wide variety of agricultural by-products for their own use. Opportunity These frontier families advanced into Illinois more quickly than existing financial institutions could supply them with money or credit. In the absence of an adequate money supply, pioneer families bartered from necessity, trading surplus home manufactures with their neighbors. One pioneer wife and mother put it simply: "For a pound of butter we paid four bushels of corn." Merchants also bowed to the inevitable and joined in the local exchange system based on barter. They accepted payment in wheat and other agricultural staples, typically advertising that groceries "will be sold low for Cash or any kind of Country Produce." Like the other pioneer families, the Lincolns participated in this system of barter and labor exchange with their neighbors. Abraham Lincoln "swapped work" with nearby families, chopping wood, railing fences, and helping with the harvest, so his family could count on their neighbors' help when they needed it. Despite their success at meeting their immediate needs, these pioneer families all recognized that Illinois needed three things to develop economically—better transportation, a more abundant money supply, and towns and cities. Even as a young man, Abraham Lincoln was determined to encourage economic opportunity and social advancement by supporting those kinds of improvements. In the spring of 1831, Abraham Lincoln decided to leave his family, forsake farming, and seek out other opportunities in the village of New Salem, where he lived for the next six years. Without efficient transportation, farmers on the Illinois frontier could not carry their produce more than twenty miles to market. They needed a village no more than fifteen miles away so they could travel there and back in a day. Rural villages therefore grew up to serve a hinterland of ten to twenty miles in radius, about the distance a farmer's wagon could travel in a day. New Salem was just such a village. The community sprang up in 1829 when two southern settlers built a mill on the Sangamon River about twenty miles downstream from Springfield. Only two years old when Lincoln arrived, New Salem was a typical frontier village, a cluster of log buildings on a New Salem offered not only employment but the chance for an education. On the Illinois frontier, educational opportunities were 4

indeed rare but not unheard of. The traditional "accidental education" afforded to young farm-boys like Lincoln, soon gave way to a more systematic, morally grounded schooling offered by common schools, academies, and eventually colleges. New Salem had a village school, and five of its youths attended Illinois College, a church-sponsored academy that opened in 1830 in the neighboring town of Jacksonville. Colleges began proliferating after 1830 as more and more farmers' sons left rural areas and began to pursue careers in towns and cities. Growing up in Kentucky and Indiana, Lincoln had attended school for a total of only one year. Later in life, he lamented that "He was never in a college or Academy as a student." Despite this "accidental education," Lincoln soon gained attention and encouragement from New Salem's elders. They organized a debating society to discuss current issues and to help educate the village's young men. Lincoln attended, gave a speech, and astonished his audience with his eloquence and poise. "As he arose to speak," Robert Rutledge recalled many years later, "his tall form towered above the little assembly. Both hands were thrust down deep in the pockets of his pantaloons. A perceptible smile at once lit up the faces of the audience, for all anticipated the relation of some humorous story. But he opened up the discussion in splendid style to the infinite astonishment of his friends." Despite his lack of formal education, Lincoln clearly possessed the potential to succeed. Self-improvement Now, as an adult, Lincoln embarked on an ambitious campaign of self-improvement. He later reminisced that he began studying English grammar at age twenty-three, "imperfectly of course, but so as to speak and write as well as he now does." Lincoln may have studied briefly with the village schoolmaster, Mentor Graham, but he was largely self-educated. In one of his autobiographies, Lincoln himself wrote pointedly—perhaps proudly—that "He studied with nobody." New Salem's settlers remembered Lincoln as a voracious reader. "Used to sit up late of nights reading," one of his friends remembered, "& would recommence in the morning when he got up." Most of his reading was utilitarian, designed to improve his mind and his prospects rather than to amuse. As Lincoln later put it, "What he has in the way of education, he has picked up." The village elders took an interest in the young man, encouraged him to study, and gave him various opportunities to grow. New Salem was a good place for a young man like Lincoln to experiment with the wide range of occupational roles that were emerging in the free society of the North. As America industrialized and urbanized in the early-nineteenth century, young men gained new freedom to pursue occupational opportunities and, in fact, could sample a wide variety of careers before choosing one to pursue, a process that historian Robert Wiebe labeled a "revolution in choices." During the six years that Lincoln lived in New Salem, he practiced nine different occupations before choosing a career. He arrived in the village as a flatboatman, floating a load of produce down the Sangamon to the Mississippi River and on to New Orleans. For a time, he helped operate the mill that was the economic foundation of the village. By his own account, Lincoln rejected a manual occupation—blacksmithing—as well as a profession—law—he "rather thought he could not succeed at that without a better education." Instead, he settled on a career as a merchant. On the frontier, merchants were important civic leaders who connected their communities to the outside world and fostered economic development and social improvement. Lincoln spent almost two years as a clerk in one store and co-owner of another. After both of the stores went bankrupt, he abandoned all thought of a career in business. His experiences as a merchant left him deeply in debt but also established his reputation as "Honest Abe" when he repaid his creditors.  The young Lincoln now "procured bread, and kept body and soul together," as he put it, by combining several part-time pursuits. He split rails, ran a mill, harvested crops, tended a still, clerked at local elections, and served as the New Salem agent for a Springfield newspaper. Eventually, three government jobs—one federal, one state, and one local—helped the young Lincoln get back on his feet. In 1833, Lincoln won presidential appointment as U.S. postmaster at New Salem. The job of postmaster was essentially a part-time position. The mails left and arrived on horseback only once a week. Most people picked up their own mail whenever they visited town to avoid paying extra postage for home delivery. As a result, Lincoln had little to do, but he held the only federal position in the village, earned the respect of the community, gained a reputation for honesty, and got to know "every man, woman & child for miles around," according to a neighbor. 5

His next appointment, as deputy county surveyor, was a another step forward. Rapid settlement of the prairie created a demand for surveyors to mark off farms, run roads, and lay out whole towns. Lincoln borrowed money for a horse, and for the next four years he rode the prairie, platting farmers' claims, drawing township lines, and running roads to open up the country. He studied surveying assiduously and developed a lifelong interest in geometry that he later recognized as an important step in his self-education. Surveying took Lincoln up to one hundred miles from New Salem, so he met people and made friends over a much wider area. His third government job, as state legislator, was the most important of all, because it launched him into a distinguished career in politics, government, and law. Politics, Government, and Law

Later in life, Lincoln proclaimed proudly that he was "Always a whig in politics." No real parties, either Whig or Democratic, had yet formed in Illinois when he arrived, but Lincoln supported the idea of an active government that would encourage economic development, create opportunity, and stimulate social development. These were central principles of the Whig Party that was emerging under the leadership of Kentucky's Henry Clay and, soon after arriving in Illinois, Lincoln proclaimed himself "an avowed Clay man." During his second year in New Salem, when he was only twenty-three, Lincoln ran for the state legislature as a representative from Sangamon County. His primary campaign promise was government support for transportation, including roads, canals, railroads, and especially the improvement of the Sangamon River, to address what he saw as the county's primary problem, access to markets. He declared that "exporting the surplus products of its fertile soil, and importing necessary articles from abroad, are indispensably necessary." He also endorsed making money more available and supporting public education to stimulate social improvement. Lincoln lost his first election but ran again and won two years later, serving a total of four terms in the legislature. He received support from Clay voters who agreed that the government should provide improvements and who gradually coalesced into the Whig Party. Throughout his four terms in the legislature, Lincoln was a leading advocate of the Whig philosophy of improvement and in particular of the economic program of his idol Henry Clay—government funded transportation, a national bank to provide a stable currency, and a protective tariff to stimulate economic growth. During his first term, Lincoln supported the creation of the State Bank of Illinois, headquartered in Springfield with branches in eight other towns. He sponsored transportation improvements in Sangamon County, including state roads running to Springfield. Dreaming of a water route linking Springfield with the Illinois River, he pushed for a canal running along the Sangamon River, which was approved but never built. More grandly, Lincoln supported construction of the Illinois and Michigan Canal and the Illinois Central Railroad. In 1836, he was re-elected to the legislature as part of the "Long Nine" who represented Sangamon County. Eight of the nine were Whigs, and they all supported an ambitious program of internal improvements, including a network of publicly financed canals and railroads, which won approval. Lincoln also played a key role in moving the state capital from Vandalia to Springfield, ensuring the economic growth and political importance of central Illinois.

During his first term in the legislature, Lincoln roomed with John Todd Stuart, another representative from Sangamon County. Stuart was a lawyer and encouraged the young man to study law. Lincoln borrowed some law books and studied them in his spare time, so even as a lawyer he was mostly self-educated. After two years, he earned his law license and 6 embarked on the career that he practiced for the next quarter century. Law opened up many more opportunities for Lincoln. Studying and Slavery and Antislavery While growing up, practicing law, and serving in government, Lincoln developed an eloquent commitment to human equality and acquired a passionate belief in the moral injustice of slavery. Lincoln's earliest experiences with slavery occurred before he arrived in New Salem. He was born in the slave state of Kentucky, and about one-eighth of the people in Hardin County, where he spent his first seven years, were slaves. Moving with his family to Indiana introduced him to a society where everyone was free and taught him the value of economic opportunity and self-improvement. When he later revisited the South, he was shocked at the inhumanity of slavery and its negative impact on both African Americans and southern whites. On one of his flatboat voyages down the Mississippi River, he saw slaves penned up in a slave market in New Orleans. His cousin John Hanks believed that this experience impressed on Lincoln an indelible hatred of slavery. "There it was we Saw Negroes Chained-maltreated-whipt & scourged," Hanks recalled in 1865. "I can say Knowingly that it was on this trip that he formed his opinions of Slavery: it ran its iron in him then & there." These early experiences as a youth helped to shape his racial views as an adult. "I am When Lincoln settled in New Salem, thirty-eight African Americans were living in Sangamon County out of a total population of thirteen thousand. Although free, they suffered a tremendous amount of legal and informal discrimination. Almost one third of them were locked into a system of perpetual servitude that resembled slavery, even in this free state. The rest were subject to the "Black Code," severe legal restrictions that singled out African Americans. Free people of color had to file a certificate of freedom at the county seat. County officials could expel any African American. Free blacks who wanted to enter the state needed to have a white resident post a $1,000 bond. The Black Code denied African Americans most legal and political rights, including the right to testify in court against whites and to vote or hold office. African Americans were also denied a host of social privileges, such as the right to marry whites. As a young legislator, Lincoln reflected traditional racial views in opposing equal rights for African Americans. During his first two terms, for example, he voted to continue restricting the elective franchise to whites. In fact, he never publicly advocated the extension of political rights to African Americans until a few days before his death. However, Lincoln was also far ahead of his time in insisting that slavery was an injustice that must be eradicated and that all people, black as well as white, had the same right to share in the kinds of opportunities for self-improvement that he and all other free Americans enjoyed. He believed that slavery not only exploited African Americans but blighted American society in general by limiting the 7

nation's potential to develop socially and economically. In 1837, a month before leaving New Salem, Lincoln took his first public stand against slavery when he and a legislative colleague declared that "They believe that the institution of slavery is founded on both injustice and bad policy" and called for the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia. This was a remarkable stand for a twenty-eight-year-old legislator from New Salem, Illinois, and it culminated twenty-six years later when President Lincoln signed both the Emancipation Proclamation and an act of Congress abolishing slavery in the District of Columbia in 1863. Fundamentally, Lincoln believed that ending slavery not only guaranteed freedom and opportunity for all Americans but was essential in promoting the nation's social and economic development. Farewell to New Salem Despite Lincoln's personal success during the 1830s, the village of New Salem slipped slowly into decline. All hopes of improving the Sangamon River to make it a viable transportation route were dashed when a steamboat, the Talisman, chugged upriver but failed to reach New Salem. When all of the new roads, canals, and railroads that sprang up bypassed the village, the little settlement's fate was sealed. In 1837, Springfield became the state capital and began drawing off both people and resources from New Salem. In 1839, the northwest corner of Sangamon County became Menard County, and the town of Petersburg, just two miles from New Salem, became the new county seat. Simply put, as transportation improved and bigger towns and cities emerged, farmers no longer needed New Salem. By 1840, a mere decade after its founding, New Salem literally disappeared. Throughout its history, the village had served an essential purpose but now had no role to play in the increasingly urban and industrial society that was emerging. Lincoln had grown considerably in New Salem—personally, professionally, and politically—but in many ways he had outgrown the village. In six years, he had risen from flat-boatman and storekeeper to state legislator and lawyer. He had embraced the village as an excellent place to work at improving himself and his society. The villagers had embraced him in return and had even sent him to the legislature, where he took a noteworthy stand against southern slavery. Now Lincoln had a profession, a law partner, and many friends waiting for him in Springfield. Full of youthful optimism, he packed his belongings into a pair of saddlebags and rode a borrowed horse the twenty miles upriver to Springfield to pursue a promising career in law and politics. At age twenty-eight, after six formative years in New Salem, Lincoln arrived in Springfield. CURRICULUM MATERIALS Overview Main Ideas Abraham Lincoln came of age in New Salem, Illinois, a rural village on the Old Northwest frontier. The biography of Lincoln during these formative years, between 1831 and 1837, sheds light on the social history of that time and place, allowing students to grasp how the Industrial Revolution transformed the American landscape. More important to the purposes of this lesson, Lincoln's New Salem years open a window on to how social history shaped his ideology—his way of thinking about the world's important issues, especially slavery. Coming of age in a setting that allowed Lincoln to climb the social ladder, from small farmer to lawyer to, eventually, president of the United States, helped form his sense of the moral superiority of a free labor system and, thus, the moral inferiority of slavery. The narrative section of the article will provide a model for conceptualizing how social history shapes ideology. Students will contrast the social history that formed Lincoln's antislavery notions with that which formed the proslavery attitude of Senator James Henry Hammond and the anti-capitalist notions of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels. Lincoln, Hammond, Marx, and Engels all framed their arguments in a similar rhetorical framework-a framework of capital and labor peculiar to the mid-nineteenth century. However, based on dissimilar social historical backgrounds, they came to very different conclusions. This is a lesson in Illinois, U.S., and comparative world history. Connection with the Curriculum This material is appropriate for both United States and Illinois history classes. These activities may be appropriate for the following Illinois Learning Standards in the Social Sciences: 14D, 15A, 15D, 15E, 16A, 16B, 16C, 16D, 18B, and 18C. Teaching Level Grades 10-12, including advanced placement courses Materials for Each Student

8

Objectives for Each Student

SUGGESTIONS FOR TEACHING THE LESSON Opening the Lesson This lesson is best taught within the context of a unit on slavery and antebellum United States. The students should already be familiar with a basic history of how slavery developed in the United States up until the 1830s. Prior to reading the Winkle article, the teacher needs to familiarize the students with the concept of social history. The class might collectively brainstorm some of the components of social history: work, family, education, religion, human migration, social movements, everyday practices, etc. Then, in groups of 4 or 5, the students should brainstorm those aspects of their own lives that might be called "social" and how social historians might one day reconstruct and document their lives. The groups should then share their ideas with the entire class. Developing the Lesson The students should be assigned to read the narrative portion of the article and Lincoln's "Address before the Wisconsin State Agricultural Society." Using these two readings, as well as a United States history textbook, the students should complete Handout 1. (Ideally, this reading and handout will be completed as homework.) The teacher should then lead a discussion of Handout 1. Concluding the Lesson After every student has a firm grasp of Handout 1, they will be given copies of the two additional readings—select passages from Hammond and Marx and Engels. In groups of 4 or 5, the students will read the passages and complete Handouts 2 and 3, using the Internet and their U. S. history books as resources. The teacher should then lead a discussion of Handouts 2 and 3, informally assessing that every student grasps the central concepts. Extending the Lesson The lesson can be extended in the form of a writing assignment based on the Handout 4 template for a written argument. The students will be making the case for one of three theories of labor: Lincoln, Hammond, or Marx and Engels. The students should either defend their preferred theory, or, to provide some balance, the teacher might assign an equal number of students to each theory. The template is presumed necessary because students need guidance in how to make a coherent and logical written argument.

Assessing the Lesson In addition to Handouts 1-3, the argumentative essay should serve as an excellent opportunity for the teacher to formally assess the students. If students have ready access to computers, the assignment should be typed. The essays should be judged according to the following three criteria:

2) Reasoning: Is the essay logical and well argued? Does it use relevant evidence to make a rational case? Does it employ critical, higher-order thinking skills? 3) Communication: Is the essay well written? Is it focused? Does the student write beautiful prose? Is it free of grammatical and spelling errors? 9 Handout 1 — Reading Comprehension: Lincoln's Formative Years at New Salem After reading Winkle's narrative and the passage from Lincoln's "Address before the Wisconsin State Agricultural Society," answer the following questions: 1. What was life like for a small farmer on the Old Northwest Frontier? Describe the family economy and the gendered division of labor in early Illinois. 2. Why did so many small farmers move north into Illinois from the states of Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee? 3. What did Illinois farm families do in the absence of a money system? 4. In its early years, what type of technological advances did Illinois need in order for its citizens to prosper economically? 5. Why was Illinois ideal for climbing the social ladder? How did Lincoln take advantage of this? 6. Describe Lincoln's education. Why was education so important? 7. What did it mean for Lincoln to describe himself as a political "whig"? 8. Why did Lincoln hate slavery? What was his attitude with regards to racial equality and why? 9. Describe the basic argument made by Lincoln in his Wisconsin address. What are capital and labor? What are his thoughts on the relationship between capital and labor? 10. How did Lincoln's early life in New Salem lead to his theory on labor? Why does Lincoln think free labor is superior to slave labor? 10 Handout 2 — Reading and Research Guide: Hammond

1. What is the "mudsill theory"? 2. Why was the mudsill theory a powerful defense of the Southern institution of chattel slavery? 3. In the North, who do you think was prone to agree with Hammond's theory regarding labor? 4. Using your textbook and the Internet, research Hammond. In 4 or 5 sentences, write a brief biography of Hammond Who was he? Where was he from? What was his profession (other than politician)? 5. Using your textbook and the Internet, research the social history of antebellum South Carolina. In 4 or 5 sentences briefly sketch this social history. Who lived there? How did the majority of South Carolinians spend their days? Describe the demographics of the state, paying particular attention to race and class. Who dominated South Carolina politics? 6. Describe how the social history of South Carolina might shape the ideology of a man of Hammond's position? How did social history shape Hammond's mudsill theory? 11 Handout 3 — Reading and Research Guide: Marx and Engels 1. Using the Internet, define the following two words from the text. a. Bourgeoisie. b. Proletariat. 2. What do Marx and Engels mean when they say that labor is just another commodity? 3. What do Marx and Engels mean when they say that the laborer has become an "appendage of the machine"? 4. Summarize Marx and Engels's theory of labor. Do you think they believe in the theory of free labor as described by Lincoln? Explain. 5. Using your textbook and the Internet, research Marx and Engels. In 4 or 5 sentences, write a brief biography of them. Who were they? Where were they from? What were their professions? 6. Using your textbook and the Internet, research the social history of mid-nineteenth century Western Europe and the northeast United States, two places where the Industrial Revolution first transformed daily living. In 4 or 5 sentences, briefly sketch this social history. What type of work did people do? What were working conditions like? Why did workers form unions and other political groups, including the Communist Party of Marx and Engels? 7. Describe how the social history of industrialism shaped the ideologies of Marx and Engels. 12 Handout 4 — Template for Making a Written Assignment Directions: Using this template, type an essay in the range of 2 pages. You will defend one theory of labor—the arguments made by Lincoln, Hammond, or Max and Engels. Author X=the author you are defending (Lincoln, Hammond, or Max and Engels). Author Y and Z=the authors you are arguing against (not X). The general argument made by Author X in his work, _________________________________________, 1This template is loosely based on Cathy Birkenstein-Graff's "Argument Machine," as cited in Gerald Graff, Clueless in Academe: How Schooling Obscures the Life of the Mind (New Haven, CH: Yale University Press, 2003), 169-70. 13 Additional Readings

Abraham Lincoln, "Address before the Wisconsin State Agricultural Society" Milwaukee, Wisconsin (September 30,1859)—Select Passages (Open Source) The world is agreed that labor is the source from which human wants are mainly supplied. There is no dispute upon this point. From this point, however, men immediately diverge. Much disputation is maintained as to the best way of applying and controlling the labor element. By some it is assumed that labor is available only in connection with capital—that nobody labors, unless somebody else, owning capital, somehow, by the use of that capital, induces him to do it. Having assumed this, they proceed to consider whether it is best that capital shall hire laborers, and thus induce them to work by their own consent; or buy them, and drive them to it without their consent. Having proceeded so far they naturally conclude that all laborers are necessarily either hired laborers, or slaves. They further assume that whoever is once a hired laborer, is fatally fixed in that condition for life; and thence again that his condition is as bad as, or worse than that of a slave. This is the "mud-sill" theory. But another class of reasoners hold the opinion that there is no such relation between capital and labor, as assumed; and that there is no such thing as a freeman being fatally fixed for life, in the condition of a hired laborer, that both these assumptions are false, and all inferences from them groundless. They hold that labor is prior to, and independent of, capital; that, in fact, capital is the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed—that labor can exist without capital, but that capital could never have existed without labor. Hence they hold that labor is the superior—greatly the superior—of capital. They do not deny that there is, and probably always will be, a relation between labor and capital. The error, as they hold, is in assuming that the whole labor of the world exists within that relation. A few men own capital; and that few avoid labor themselves, and with their capital, hire, or buy, another few to labor for them. A large majority belong to neither class—neither work for others, nor have others working for them. Even in all our slave States, except South Carolina, a majority of the whole people of all colors, are neither slaves nor masters. In these Free States, a large majority are neither hirers or hired. Men, with their families—wives, sons and daughters-work for themselves, on their farms, in their houses and in their shops, taking the whole product to themselves, and asking no favors of capital on the one hand, nor of hirelings or slaves on the other. It is not forgotten that a considerable number of persons mingle their own labor with capital; that is, labor with their own hands, and also buy slaves or hire freemen to labor for them; but this is only a mixed, and not a distinct class. No principle stated is disturbed by the existence of this mixed class. Again, as has already been said, the opponents of the "mud-sill" theory insist that there is not, of necessity, any such thing as the free hired laborer being fixed to that condition for life. There is demonstration for saying this. Many independent men, in this assembly, doubtless a few years ago were hired laborers. And their case is almost if not quite the general rule. James Henry Hammond (U.S. Senator, South Carolina), "The Mudsill Theory" Speech before the U.S. Senate (March 4,1858)—Select Passages (Open Source) In all social systems there must be a class to do the menial duties, to perform the drudgery of life. That is, a class requiring but a low order of intellect and but little skill. Its requisites are vigor, docility, fidelity. Such a class you must have, or you would not have that other class which leads progress, civilization, and refinement. It constitutes the very mud-sill of society and of political government; and you might as well attempt to build a house in the air, as to build either the one or the other, except on this mud-sill. Fortunately for the South, she found a race adapted to that purpose to her hand. A race inferior to her own, but eminently qualified in temper, in vigor, in docility, in capacity to stand the climate, to answer all her purposes. We use them for our purpose, and call them slaves. We found them slaves by the common "consent of mankind," which, according to Cicero, "lex naturae est." The highest proof of what is Nature's law. We are old-fashioned at the South yet; slave is a word discarded now by "ears polite;" I will not characterize that class at the North by that term; but you have it; it is there; it is everywhere; it is eternal. The Senator from New York said yesterday that the whole world had abolished slavery. Aye, the name, but not the thing; all the powers of the earth cannot abolish that. God only can do it when he repeals the fiat, "the poor ye always have with you;" for the man who lives by daily labor, and 14 scarcely lives at that, and who has to put out his labor in the market, and take the best he can get for it; in short, your whole hireling class of manual laborers and "operatives," as you call them, are essentially slaves. The difference between us is, that our slaves are hired for life and well compensated; there is no starvation, no begging, no want of employment among our people, and not too much employment either. Yours are hired by the day, not cared for, and scantily compensated, which may be proved in the most painful manner, at any hour in any street in any of your large towns. Why, you meet more beggars in one day, in any single street of the city of New York, than you would meet in a lifetime in the whole South. We do not think that whites should be slaves either by law or necessity. Our slaves are black, of another and inferior race. The status in which we have placed them is an elevation. They are elevated from the condition in which God first created them, by being made our slaves. None of that race on the whole face of the globe can be compared with the slaves of the South. They are happy, content, unaspiring, and utterly incapable, from intellectual weakness, ever to give us any trouble by their aspirations. Yours are white, of your own race; you are brothers of one blood. They are your equals in natural endowment of intellect, and they feel galled by their degradation. Our slaves do not vote. We give them no political power. Yours do vote, and, being the majority, they are the depositories of all your political power. If they knew the tremendous secret, that the ballot-box is stronger than "an army with banners," and could combine, where would you be? Your society would be reconstructed, your government overthrown, your property divided, not as they have mistakenly attempted to initiate such proceedings by meeting in parks, with arms in their hands, but by the quiet process of the ballot-box. You have been making war upon us to our very hearthstones. How would you like for us to send lecturers and agitators North, to teach these people this, to aid in combining, and to lead them? Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, "The Manifesto of the Communist Party" Germany (February 1848)—Select Passages (Open Source) In proportion as the bourgeoisie, i.e., capital, is developed, in the same proportion is the proletariat, the modern working class, developed—a class of labourers, who live only so long as they find work, and who find work only so long as their labour increases capital. These labourers, who Owing to the extensive use of machinery, and to the division of labour, the work of the proletarians has lost all individual character, and, consequently, all charm for the workman. He becomes an appendage of the machine, and it is only the most simple, most monotonous, and most easily acquired knack, that is required of him. Hence, the cost of production of a workman is restricted, almost entirely, to the means of subsistence that he requires for maintenance, and for the propagation of his race. But the price of a commodity, and therefore also of labour, is equal to its cost of production. In proportion, therefore, as the repulsiveness of the work increases, the wage decreases. Nay more, in proportion as the use of machinery and division of labour increases, in the same proportion the burden of toil also increases, whether by prolongation of the working hours, by the increase of the work exacted in a given time or by increased speed of machinery, etc. Modern Industry has converted the little workshop of the patriarchal master into the great factory of the industrial capitalist. Masses of labourers, crowded into the factory, are organised like soldiers. As privates of the industrial army they are placed under the command of a perfect hierarchy of officers and sergeants. Not only are they slaves of the bourgeois class, and of the bourgeois State; they are daily and hourly enslaved by the machine, by the overlooker, and, above all, by the individual bourgeois manufacturer himself. The more openly this despotism proclaims gain to be its end and aim, the more petty, the more hateful and the more embittering it is. No sooner is the exploitation of the labourer by the manufacturer, so far, at an end, that he receives his wages in cash, than he is set upon by the other portions of the bourgeoisie, the landlord, the shopkeeper, the pawnbroker, etc. 15 |

|

|