|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

1 • 8 • 6 • 2

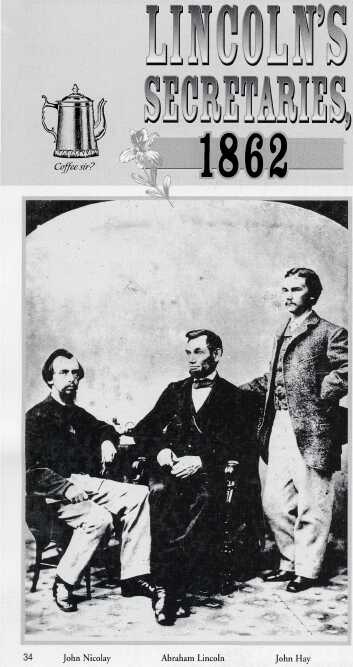

Jennifer L. Weber John Hay and John Nicolay were young men when they went to work as personal secretaries to President Abraham Lincoln. Neither was yet thirty. But Hay and Nicolay, who lived in the Executive Mansion, became quite close to Abraham Lincoln, and the two may have spent more time with him than anyone else did during his presidency. They certainly had a more intimate view of the president than anyone other than his wife during his first term in office. They later wrote a ten-volume biography of Lincoln, and their letters and diaries offer unique observations of the man who led the nation through the greatest crisis it has ever faced. The two men hardly seemed fated for such a brush with greatness. Nicolay was a dyspeptic German immigrant who had been a newspaperman and then assistant to Ozias Hatch, the Illinois secretary of state and a friend of Lincoln's. Overwhelmed with mail in the days after his nomination as the Republican presidential candidate, Lincoln hired Nicolay first to be his personal secretary. Hay, a spirited but snobby young man whom Lincoln came to regard almost as a surrogate son, was a graduate of Brown and had been halfheartedly studying the law in Springfield when he was chosen to help Nicolay deal with the president-elect's mail. Once in the Executive Mansion, Nicolay and Hay worked long days—often twelve to fourteen hours, and sometimes as many as twenty. Nicolay described his routine as "a sort of treadmill which promises little else than weariness and disgust at the end of each day's task." But both men acknowledged that their labor was light compared to Lincoln's. The president, who was twice their age, worked harder than did they or anyone else in the administration. The year 1862 was almost bipolar in its highs and lows. That year Union troops achieved their first great successes, especially in the West. It was the year Lincoln issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which changed the war from one for reunion to one for freedom, too. But it was also the year that federal forces, particularly the Army of the Potomac, suffered their first major setbacks. That summer was so bad militarily that many civilians in the North talked openly of giving up 34

the fight. After a draw in September at Antietam, the bloodiest single day in American history, the Union went on to take a horrible beating in early December at Fredericksburg. The first successes came in February, with Ulysses S. Grant's victories at Forts Henry and Donelson in Tennessee. These were the first major breakthroughs for the Union army. Lincoln credited the can-do spirit of the West, saying privately, "I cannot speak so confidently of the fighting qualities of the Eastern men, or what are called Yankees ... but this I do know—if the Southerners think that man for man they are better than our Illinois men, or western men generally, they will discover themselves in a grievous mistake." Grant's achievements created a stir in the Northern public, but their impact was blunted in the Executive Mansion, as the White House was known at the time, by the death of Lincoln's favorite son, eleven-year-old Willie. He had contracted typhoid, and Lincoln was "very much worn and exhausted" from worry, Nicolay said. About 5 p.m. on February 20, Nicolay was lying on the sofa in his office when the president came in. "Well Nicolay, my boy is gone—he is actually gone!" Nicolay wrote in his diary. Then, "bursting into tears," Lincoln turned and walked into his own office. For some time after Willie died, the usually hardworking Lincoln took Thursdays off in memory of his son. His family had joined the legions of Americans who had lost a child, a father, a husband during the war. The secretaries' main loyalty was to Lincoln, whom they affectionately called "the Tycoon," and they had little use for the president's family. Hay and Nicolay did not care for the two younger Lincoln boys, whom they regarded as spoiled and out of control, and they especially disliked Mary Lincoln, whom they privately referred to as "the Hell-Cat." Their contempt for the first lady stemmed from her general disposition and willingness to defraud the government. She could make their lives miserable. Writing to the absent Nicolay in April, Hay declared, "There is no fun at all. The Hellcat is getting more Hellcattical day by day." Despite the hours and the difficulty of dealing with Mrs. Lincoln, Hay and Nicolay found plenty of time for pleasure. Both were still single, and they were deeply involved in Washington's social scene. They went to every party they could, flirted with any attractive young woman they encountered, and lapped up the gossip. "Madames Lisboa & Asta Buraga have had an awful quarrel originating in the Brazilienne uttering disrespectful opinions of the Chilienne's nose," Hay reported to Nicolay in late March. Winter receptions at the Executive Mansion were the exception to their general enjoyment of parties. Nicolay granted that these might be "both novel and pleasant"

"Well Nicolay, my boy is gone—he is actually gone!" 35

to Washington visitors, "but for us who have to suffer the infliction once a week they get to be intolerable bores." The lively tempo of Washington society may have eclipsed battlefield worries for brief periods, but never for long. In April, Grant was on the move again. After a faltering start at Shiloh, on the Tennessee River, he pulled off a notable victory. It was not without cost, though. Shiloh was the bloodiest battle in the history of North America to that time, claiming nearly 24,000 casualties (killed, wounded, captured, and missing). The battle stripped away any lingering belief on either side that the Civil War could be short or relatively bloodless. Grant then went on to take Island No. 10, opening yet more of the Mississippi to Union gunboats and traffic. At the end of April, New Orleans and the southern part of the river fell to the federals. In early June, the Yankees captured Memphis. The federal forces had the rebels on the run in the West.

In the East, the situation was different. Confederate General Stonewall Jackson spent a good part of the spring moving up, down, and through Virginia's Shenandoah Valley, utterly outwitting the enemy. The federals simply could not respond adequately to an army that knew the terrain and used it so well to ts advantage. But the most persistent problem for Lincoln in the East was General George B. McClellan, commander of the Army of the Potomac. Little Mac, as he was known to an admiring public, was a cautious leader, to say the least. He cared deeply for his troops but not much for fighting, and his dismay over the prospect of losing his men got worse after his first major battle, at Seven Pines in Virginia. There, at the end of May 1862, he seemed unstrung by the sight of dead and wounded bluecoats. The timing for his fading of heart could hardly have been worse, since the very aggressive Robert E. Lee took command of the Army of Northern Virginia after that very same battle. From that point on, McClellan would be more reluctant than ever to go into battle, often claiming that the enemy vastly outnumbered him. Never mind the reality of numbers; the threat of being Lincoln's secretaries were persistently disgusted with General McClellan. Even before Seven Pines, Nicolay thought that the Army of the Potomac could not win as long as McClellan commanded it. The general's lolly-gagging in 1862 constantly tormented Nicolay. "I am beginning to feel that the apprehension of defeat [by McClellan] is worse than defeat itself," he wrote his sweetheart back home in Illinois. But it was not just McClellan's timidity that bothered Hay and Nicolay. They also found him to be terribly rude to Lincoln—nearly to the point of insubordination. They also questioned his agenda, wondering whether his real plan was to run for president (he was, in fact, the Democratic candidate in 1864). 36

Even before Seven Pines, Nicolay thought that the Army of the Potomac would need a new commander before it logged any victories. Lincoln continually had to prod the reluctant general to act, and at the end of June, Little Mac finally made his move on Richmond, launching what was has come to be known as the Seven Days' Battles. Despite a reasonably good showing in the first couple of days, McClellan tried to withdraw. Lee pursued him, and after several days of inconclusive fighting, Union forces whipped the rebels at Malvern Hill. Still, McClellan was intimidated enough by Lee to back far down the Virginia Peninsula rather than move on Richmond. It looked like retreat, Nicolay said, and "everybody here has been terribly blue about it...." Many people in the North were ready to give up, with the notable exceptions of Lincoln and his cabinet. Nicolay could not believe that even many of the nation's leaders had "so little real faith and courage under difficulties.... A single reverse of piece of accidental ill-luck is enough to throw them all into the horrors of despair." The real despair, though, would come late in August. Lee had taken note of McClellan's tentativeness and decided to move north. A frightful second battle at Manassas (also known as Bull Run; the first battle took place there in July 1861) resulted in a severe thrashing for the Union, whose losses numbered 5,500 more men than the Confederates. At Second Manassas, McClellan refused to come to the aid of the commander on the field, General John Pope. According to Hay, Lincoln said that "it really seemed to him that McC wanted Pope defeated.... The President seemed to think him a little crazy," and blamed jealousy and spite for his conduct. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton suggested that McClellan be court-martialed. The import of Second Manassas cleared the way for Lee to move into Maryland. Lee thought he might be able to pry Maryland loose from the United States, prompting England and France to recognize the Confederacy. He also wanted to get the armies out of northern Virginia, where marching and fighting had taken a serious toll on the local farms and economy. The battle could have been a huge victory for the Union in the hands of a more aggressive general. Lee's battle plan had fallen into McClellan's hands on September 13, but Little Mac waited eighteen hours before even beginning to act on this intelligence boon. By that time, Lee was already moving to shore up his defenses. The two armies finally met on September 17 outside the small town of Sharpsburg, Maryland. The battle that took place there—Antietam— proved to be the single bloodiest day in American history, with more than 21,000 casualties, four times more than on D-Day. So many men fell in some places that a person could not walk without stepping on bodies. Mathew Brady sent a team to take pictures, and they caused a sensation when Brady posted them in his New York studio. It was the first time Americans had seen battle photographs. The battle was a draw, but Lincoln claimed it as a victory, one that gave him the leverage he needed to make his most audacious announcement of the war: the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Lincoln had always been opposed to slavery but thought 37

the Constitution limited his ability as president to end it. Unknown to anyone but his cabinet, Lincoln had drafted the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in July. Hay had sensed something was up, confiding to a friend that month that the president "will not conserve slavery much longer.... Even now he speaks more boldly and sternly to slaveholders than to the world." After drafting the proclamation, Lincoln waited for a victory so that it would not look like a last-ditch measure. With his claim that Antietam was a victory, he could issue the document. The cabinet "all seemed to feel a sort of new and exhilarated life; they breathed freer; the Prest. Procn. had freed them as well as the slaved," Hay wrote in his diary. In fact, at that moment, the proclamation had freed no one, but it would as more slaves escaped to army lines and as the armies moved deeper south and claimed more territory. More importantly, it added a moral dimension to the war. Still, the proclamation was very controversial, especially within the army's ranks, and Republicans paid for it at the polls in November. They lost seats in Congress, along with the governorships of New York and New Jersey and the state legislatures in Indiana and Illinois. Peace Democrats fueled by anger over the Emancipation Proclamation, which they considered unconstitutional, had a notably good showing, especially at the state level. Republicans could take some consolation that their losses in the off-year election were not as bad as usual for the party in power, but there was no denying the political reality.

Events moved quickly, though, and within days Lincoln's attention was back on military matters. In October, Confederate cavalry commander Jeb Stuart had dashed into Pennsylvania and ridden around McClellan's army before returning to Virginia. "The President has well-nigh lost his temper over it," Nicolay wrote his sweetheart. This was unusual behavior for the equable Lincoln. Nicolay, a prickly man himself, did not regard Lincoln's patience as necessarily a virtue. "I wish," Nicolay mused, "he would sometime get angry enough to dismiss about half the officers in the army—I think the remaining half would do more work and do it better by the example...." By early November, Nicolay despaired of removing McClellan. But even Lincoln had his limits, and the balky and insubordinate general finally found them. Right after the election, the president reluctantly fired him. The secretaries were elated. The new head of the Army of the Potomac had little better luck than McClellan, though. Ambrose Burnside told Lincoln he did not think himself capable of command, and he was right. His first battle, at Fredericksburg, Virginia, was proof. Pontoons were late in arriving for the Federals to cross the Rappahannock and move on the town, giving the Rebels plenty of time to prepare. Then the Union forces moved across open ground to try to attack Confederates who were behind a stone wall. It was a disaster, made worse when the wounded froze to death the night after the battle. The loss cut deeply, and Nicolay was still morose over that and other military failures at the end of the year. "If you ask me when all this is to cease or be changed, I am really unable to answer. I suppose when Providence interferes to give our generals a little sense or skill." The Union had plenty of men and supplies, but the setbacks on the field led Nicolay "at last to believe the military genius is not as plenty as blackberries in our armies. Nevertheless, my faith is yet unshaken, and my arbor unquenched. We must and will succeed." Three days later, the Emancipation Proclamation went permanently into effect. The author would like to thank the White House Historical Association for its support of this project. 38  Monica Cousins Noraian Overview Main Ideas What we know about the past is what was recorded by those who were there. Images and voices tell the story of history. As historians it is your job to piece the past together to tell a story of what happened through the use of primary and secondary documents. As students of history it is your job to read, listen, and look to the past to gain understanding and meaning. History is studied through primary and secondary sources. What we know about the past is based on both forms of information. History is recorded by those who experience it and then interpreted by those reading it. We develop historical empathy and understanding based on what we read, learn, and discover about other people's lives, experiences, and past events. These three lesson activities along with the article will help students learn more about historical events of the year 1862 and their impact. Connection with the Curriculum This material could be used to teach United States history. The activities may be appropriate for Illinois Learning Standards 16. A. 3; 16 A. 4; 16. A. 5; 16. B. 3; 16 B. 4; 16. B 5; 16. D. 3; 16. D. 4; 16. D. 5; 16. E. 3; 16. E. 4; 16. E. 5; 18. A. 3; 18. A. 4; 18. A. 5; 18. B. 3; 18. B. 4; and 18. B. 5. Teaching Level The reading and activities are appropriate for grades 6-12. The ability and age of the students will determine the level and depth of research, written work, peer review, and presentation. Materials for Each Student

Objectives for Each Student Students will

Opening the Lesson As a set induction, ask students to share about the year 2008 (or a year they can all remember). On the board record the events that come to mind for them. They should include personal, school, community, state, national, and world events. In small groups ask them then to think about the impact of those events on various groups. They should think about how the events impact them, their family, their school, their community and the larger society around them. End with questions like: Is this history? Who records what happens? How do we know what we know about events? Introduce the reading "Lincoln's Secretaries, 1862." This reading focuses on events from the year 1862 as recorded by Lincoln's personal secretaries, John Hay and John Nicolay. While reading the article, students should pay attention to the people, and the events and their impact on others. Have students share their list on the board: People—Events—Possible Impact Developing the Lesson The following three activities expand on the material presented in "Lincoln's Secretaries, 1862," the Civil War during 1862, key players, historical empathy, action-reaction, and cause-effect concept. The teacher could assign all three activities, select one or give students a choice. Each one is different and independent but all build on the concepts from the reading. Activity One From the Library of Congress American Memory site, view the Civil War time line for the year 1862. Click on photographs of the battles and images of war. Complete the 39

guiding questions. This was the first photographed war, and the images are a powerful record of the first modern war. See Handout for Activity 1. Activity Two Have students read the article and then pick one of the historical characters mentioned for further study. Using the textbook, appropriate Internet sources, or the library, find out a little more about this person you selected and some of their experiences during the Civil War period. At http://www.mrlincolnswhitehouse.org, click on Mr. Lincoln and then use the site Menu to select specific people of interest. The personal and professional events that transpired in the year 1862 had a tremendous impact on Lincoln as was recorded by his two personal secretaries, John Hay and John Nicolay. Daily events have an impact on everyone. Students will write a diary entry from their character's perspective describing an event and its impact on his or her life. Students can get creative with the assignment, but the diary entry should be based on history and include a little factual information about the person writing and historical events. Character list:

b. Lincoln's son Willie (William) Lincoln c. Lincoln's wife Mary Todd Lincoln d. Secretary John Hay e. Secretary John Nicolay f. General Ulysses S. Grant g. General Stonewall Jackson h. General George B. McClellan i. General Robert E. Lee j. An African-American affected by the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation k. An everyday soldier in the army l. An everyday resident in the United States m. A member of Congress The next day students should share their diary entries with a classmate for peer review and feedback. Use the following diary checklist for peer evaluation: _____Diary entry format Reaction and Comments: Activity Three Have students create a newspaper, talk show, or newscast for the year 1862. Have students pick topics that emerge out of the article for further study and exploration. Illustrate with drawings, maps, paintings, political cartoons, or period photographs. Review the parts of a newspaper, a talk show, or newscast. This preparation step could be assigned for homework and shared with classmates the next day as a brainstorming session to help everyone get started. Students should also review historic newspapers, photographs, or magazines. What seem to be included elements? What are topics of discussion? This can be done with sources from your local historical society, library, or internet. Harper's Weekly is a wonderful Civil War period circular that you may view on the Internet at http://www.sonofthesouth.net/ leefoundation/civil-war-1862.htm Review Harper's Weekly from 1862 and have students identify its different topics or sections. Explore a few editions of Harper's Weekly and answer the following for each. Issue date: In small groups, students should develop their own Civil War newspaper reports for the year 1862. Students should be creative and include several of the following in their work:

40 You might ask students to select one of the following topics addressed in the article on "Lincoln's Secretaries, 1862" for their newspaper reports:

Concluding the Lesson Once newspapers, talk shows, or newscasts are completed, have students share them with others in the class. Set up a newspaper reading time or TV time where students get to experience the work of their classmates. It is wonderful for students to have the opportunity to share their work with others. Students should give feedback based on their reading of the papers or viewing of the productions. As a conclusion to the lessons, link back to the set induction and ask students to share examples of people and events from the year 1862. List these on the board and see if students can identify the impact these events had on the individuals. Reinforce the examples used in the reading "Lincoln's Secretaries, 1862." Extending the Lesson This lesson focuses on the year 1862. The ideas could be introduced with any unit topic or period. The lesson objective—"post-holing" a particular time period and having students explore the impact of historical events on those experiencing them—could be employed with other units. Assessing the Lesson This lesson allows for several points of varied assessment and checks for student understanding throughout. The guided set-induction questions and brainstorming session check for student readiness and comprehension of the article reading. The three activities have handouts with them to assist in guiding the learning and assessment process. The final product of a reproduction— 1862 newspaper—will be assessed both formally by the teacher and informally by student feedback. 41 Activity 1

View the Civil War time line for the year 1862 from the Library of Congress American Memory site (http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/cwphtml/tl1862.html) Click on photographs of the battles and images of war. Complete the guiding questions. This was the first photographed war, and the images are a powerful record of the first modern war. Select two photographs to answer questions about. A. Battle Information: List the name/date Photo Information: List the image title/date Image Description:What do you see? Who or what is in the picture? What does it illustrate or tell you about the period? Image Reaction: What might onlookers or the photographer be thinking? How does it make you feel? B. Battle Information: List the name/date Photo Information: List the image title/date Image Description: Who or what is in the picture? What does it illustrate or tell you about the period? Image Reaction: What might onlookers or the photographer be thinking? How does it make you feel? 42 Activity 2 Select a person of interest to you from the year 1862. Find out a little about him/her and some events from the period they experienced. Notes:

Person's Name: Three facts about him/her: One thing he/she experienced during the year 1862: Write a diary entry for this person. Include facts about his/her life, things he/she experienced, and his/her reactions to them. Dear Diary, Date: The next day, share the diary entries with a classmate for peer review and feedback. Use the following diary checklist for peer evaluation: _____Diary entry format Reaction and Comments: 43 Activity 3 As preparation for developing your own newspaper, talk show, or newscast you need to review some contemporary and historical examples. Newspaper Name: Describe three sections inside the paper: Describe the illustrations or political cartoons: Describe an advertisement: Harper's Weekly is a wonderful Civil War period circular. Review an issue from 1862. at: http://www.sonofthesouth.net/leefoundation/civil-war-1862.htm Explore a few editions of Harper's Weekly and answer the following for each. Issue Date:

Describe three sections Inside the Harper's Weekly. What information did you find that interested or surprised you? List some headlines: Describe a political cartoon: Describe an advertisement (want ad or product): How did this 1862 edition compare to the contemporary paper you reviewed? 44 |

|

|