|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

1 • 8 • 6 • 3

LINCOLN AT GETTYSBURG Barry Schwartz Knowing what Abraham Lincoln meant when he wrote the Gettysburg Address, how his own audience and later readers understood it, and what its consequences were clarifies a vexing problem: how are we to judge varying interpretations of historical events? Some people have observed aspects of the Address not visible to others, while some have viewed the address and come to unfounded conclusions. How to distinguish between these two visions is our question. No one can know for certain what went through Abraham Lincoln's mind as he wrote the Gettysburg Address, but one can reconstruct the setting that made his words meaningful. The battles at Gettysburg left almost 3,000 Union men dead, 6,643 missing, and 13,709 wounded. David Wills, organizer of the Gettysburg Cemetery dedication, invited Lincoln to comment on the nation's gratitude to the war dead and to explain the meaning of their sacrifice. To do so, Lincoln had to know not only what the war meant to its survivors but also what they were prepared—and not prepared—to die for. Lincoln's own words at Gettysburg may have affected those who heard or read them, but most literate Americans in 1863 never knew what he had said. Of 35 newspapers studied, including Democratic and Republican, southern and northern, eastern and western papers, 11, or about 31 percent of the total, made no mention of Lincoln's comments. Seventeen newspapers, a little less than half, reprinted his Address without comment, most along with Edward Everett's oration. The six newspapers that did assess Lincoln's words split along party lines. Democratic newspapers attacked him. For the Harrisburg Patriot and Nation, the entire dedication ceremony was a "panorama that was gotten up more for the benefit of [Lincoln's] party than for the glory of the nation and the honor of the dead." 45 Republican editors, on the other hand, remarked on the beauty of Lincoln's words and on how they stirred feelings of militancy: "More than any other single event," the Gettysburg Times reported, "will this glorious dedication nerve the heroes to a deeper resolution of the living to conquer at all costs." The Boston Transcript's editor, likewise, noted: "The ideas of duty are almost stammered out... as the inspiration not only of public opinion, but of public action also. One sentence should shine in golden letters throughout the land as an

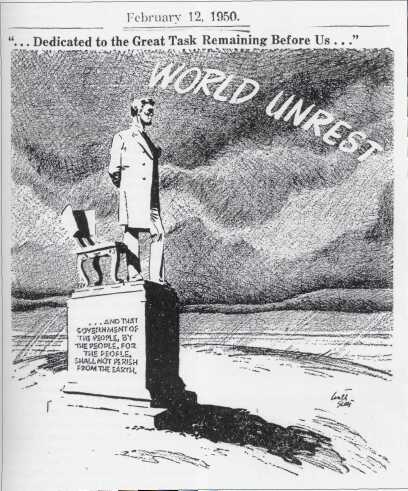

exhortation to wake up apathetic and indolent patriotism. 'It is for us the living rather to be dedicated here to the unfinished work that they have thus far so nobly carried on."' Harper's Weekly also recognized the militancy of Lincoln's words and the tone of the dedication: "More Few of Lincoln's contemporaries had reason to remember his Gettysburg speech. Neither the press nor the public recognized it as a great oration; few intellectuals described it as such. Not one lithograph or statue of Lincoln at Gettysburg appeared during or after the Civil War. Not until the early twentieth century, when an industrial democracy replaced a rural republic and Lincoln's renown crystallized, did his speech become part of the "New Testament" of America's civil religion. "The true applause" for the Address, Charles E. Thompson wrote in 1913, "comes from this generation." Major William H. Lambert told the Pennsylvania Historical Society that none of Lincoln's contemporaries saw unusual merit in his Gettysburg Address. "It is difficult to realize that [the Address] ever had less appreciation than it does now." Lincoln's statement, read in the context of Progressive reform and World War I, evolved into an "Americanist" interpretation of democracy. In November 1863, editorial reactions made infrequent reference to democratic government; by 1918, that theme had become prominent. Junius B. Remensyder, present at the Gettysburg dedication, recalled in 1918 how Lincoln had eased the burden of the people by revealing "the generic truths of democracy." That revelation, concerning government of, for, and by the people, would become a battle cry and appear frequently on war bond announcements (figure, page 49). The meaning of February 12, Lincoln Day, declared the President of Mills College to a rally of 300 students, "is that we once more dedicate ourselves to an unfinished task." The Gettysburg Address was read to mass meetings everywhere, and the war rhetoric enveloped itself in its words: "Let us all highly resolve," declared the Newark News editor, "to dedicate ourselves wholeheartedly to war work ... so that liberty shall not perish from the earth." With the war over, U.S. Representative Wells Goodykoonts called the Address "the most perfect definition ever given of the word democracy," Representative Albert Griffith found in it "the mighty reality, the fundamental essential," of "people's government." These ideas reverberated through the writings and populist art work of the 1920s and Great Depression (figure, page 45). What people say when their nation's existence is in peril tells us something about the events that inspire them. Lincoln at Gettysburg was invoked more often during the Second World War than ever before. "A new birth of freedom" meant military victory. 46

That democratic government "shall not perish from the earth" now meant that it would prevail over fascism. The most frequently

quoted line during World War II was "It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have Seven years later, Representative Louis B. Heller of New York marked the invasion of South Korea by inserting into the Congressional Record a recent New York Times article by M.L. Duttus. "The cause for which the men who fell at Gettysburg gave the last full measure of their devotion has not... won the final victory." In the face of the communist menace, "anxious humanity still yearns for a new birth of freedom"—still yearns, that is, for permanent security against tyranny's forces (figure, above). As the 1960s approached, civil rights issues were superimposed on questions of war and peace. By the middle of the decade, Americans began to read the Gettysburg 47

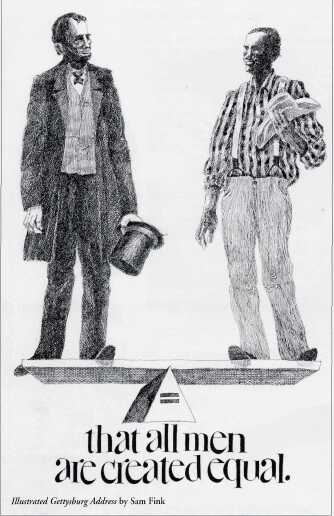

Address almost exclusively through the lens of racial conflict. Because "Lincoln's reaffirmation of the American commitment to the 'proposition that all men are created equal' had been preceded by the Emancipation Proclamation," he must have meant emancipation to be the first step toward racial integration, declared Secretary of State Dean Rusk at the Gettysburg Address centennial celebration. Poet Archibald MacLeish was present at the centennial, too, and he echoed Rusk's thought: "[T]here is only one cause to which we can take increased devotion"—the cause of race relations. "Lincoln would be disappointed at the slow pace of their improvement." William Scranton, Republican Governor of Pennsylvania, amplified Rusk's and MacLeish's comments by including the civil rights issue in his official centennial address: "Today, a century later, our nation is still engaged in a test to determine if the United States, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal, can long endure. Blood has been shed in the dispute over the equality of men even in 1963." For E. Washington Rhodes, African American editor of the Philadelphia Tribune, the civil rights struggle proved that the "hopes of Abraham Lincoln for a united nation remain unrealized, unfulfilled in American life." Clearly, Rusk, MacLeish, Scranton, and Rhodes saw Lincoln at Gettysburg announcing his vision of a racially integrated society. During the last decade of the twentieth century, the Declaration of Independence assumed unprecedented importance as a frame for understanding the Gettysburg Address. Garry Wills's Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words That Changed America is the pioneering statement. Asserting that the Gettysburg speech transformed America into an egalitarian society, Wills presents a great man theory of history. No longer was Abraham Lincoln the symbol of equality, but its maker; no longer the personification of America, but the ultimate source of its virtue. No longer was the Gettysburg Address a mere eulogy; it was a formative event in its own right, shaping America's social and political life. Distinguishing between a Declaration of Independence affirming the equality of all men and a Constitution legitimating slavery, Wills asserts that Lincoln invoked the 48

Address was a "preamble," subordinated Union to racial equality—a point articulated visually as well as verbally (figure, p. 48). Saving the Union, Meyer adds, was not good enough. The Union had to be kept "forever worthy of saving," which would be possible only if it were free of slavery. To that end, David Blight declared, Lincoln took the country to war. "Only in the killing, and yet more killing if necessary," "would come the rebirth-a new birth of the freedoms that a republic makes possible." Such was Lincoln's chilling message to the grieving masses at Gettysburg Cemetery. Or so it seems. The Gettysburg Address, clearly, means different things to different generations. Lincoln's contemporary supporters believed the Address to be a call to finish the fight. At the turn of the twentieth century, people believed he was talking about the preservation of democratic government. During World War I, the Address again became associated with military goals; during the Depression the theme of American democracy reappeared. Through World War II, the Address's militant and consoling potential again became manifest; afterward, the peacetime interpretation, gratitude to the men who saved democracy for the world, reappeared. During the last third of the twentieth century, however, the Address became a plea for racial integration and has remained so ever since. Because any one of these themes—winning the war, saving democracy, racial justice—can be read into Lincoln's oration, we find ourselves in the position of having to say either that the Gettysburg Address has multiple meanings or that one of these meanings corresponds more closely to Lincoln's intentions than others. Each assertion is plausible. The enemy's defeat was, in truth, the only means of saving democracy and ending slavery. That Lincoln's dedication told the people his war goal included emancipation is also convincing. The emancipationist interpretation is, indeed, the most direct and simple, and it most readily explains the connection among Lincoln's most quoted phrases. His opening words, "Fourscore and seven years ago," immediately brings to mind the Declaration of Independence and the fact that slavery's preservation was a necessary condition for all colonies endorsing it. Because slavery was in jeopardy in late 1863 and black soldiers were already fighting for the Union cause, how could anyone listening to Lincoln's speech fail to associate his "new birth of freedom" with emancipation? In this connection, the Chicago Times, one of the most influential opposition newspapers, condemned Lincoln for using a funeral eulogy as the occasion to promise to make blacks and whites equal. How dare he deny the true cause for which they died! The fallen of Gettysburg "were men possessing too much self-respect to declare that negroes were their equals, or were entitled to equal privileges." Abolitionists drew an opposite yet comparable conclusion. The Harrisburg Telegraph's editor believed emancipation, not Union, or, at least, not Union alone, justified the war: "To approach the grave of a Union 49

soldier, and not approve of abolitionism, would be equal to approaching the shrine of religion and not praying to the only true and living God." That the salvation of democratic government was the purpose of the Civil War is no less evident in Lincoln's words. "We are on this battlefield to determine whether any nation so conceived [in liberty and equality] can long endure." We owe the soldiers our gratitude, for they died to ensure "that government of the people, by the people, and for the people shall not perish from the earth." Today, democratic government is so firmly entrenched in the United States and Europe that it is difficult to think of its being at stake in the outcome of the Civil War, but in the mid-nineteenth century nothing was less certain than America's remaining the world's only democracy. Most European political philosophers believed only authoritarian regimes could ensure order, while monarchs and aristocratic elites had recently defeated democratic movements. After the Confederate states resorted to force of arms after losing the 1860 election, many mid-nineteenth-century American leaders believed the New Republic was an experiment that might fail. If Lincoln at Gettysburg meant to convey what was at stake for the future of democracy, as was believed throughout most of the twentieth century, then his opening phrase, "Fourscore and seven years ago [1776]," his invocation of the Declaration of Independence's "proposition that all men are created equal," and his dream of "a new birth of freedom" must refer to something other than emancipation. Among a religious people believing in divine intervention, July Fourth must have been a day of wonder: on July 4,1776, America was born; on July 4, 1826, two of "our fathers" who brought forth the nation, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, died; on July 4,1831, James Monroe, a third founding father, died; on July 4, 1863, the city of Vicksburg surrendered, the Confederate Army retreated from Gettysburg, and the embattled Union turned the tide of war. Lincoln recognized these connections in his July 7,1863, comments: "Gentlemen, this is a glorious theme, and the occasion for a speech, but I am not prepared to make one worthy of the occasion." Lincoln thought about July Fourth, the Declaration of Independence, and equality as did many Americans. Before 1815, according to historian Pauline Meier, the Declaration's equality proposition referred to the relations between colonists and residents of the Mother Country; after 1815 it was "sacralized" and deployed by every interest group seeking the moral high ground, including workers, farmers, women's rights advocates, antislavery interests, and abolitionists. As America's credo, Lincoln naturally invoked it at Gettysburg, for no other phrase expressed better the ideals of the day or justified sacrifice on their behalf. "The proposition that all men are created equal" now meant that all citizens, although stratified in terms of talent, virtue, and endowment, are equal in terms of legal rights and economic opportunity. Lincoln and his fellow Republicans included blacks in this principle, but that did not imply racial integration as a social goal. The third phrase around which Gettysburg Address explication winds itself is "New birth of freedom." "What [Lincoln] meant by 'a new birth of freedom' for the nation," Carl Sandburg observed, "could have a thousand interpretations;" yet, some are more reasonable than others. A new birth resulting from the purging of "the terrible sin of slavery," as Svend Petersen put it, might have made more sense in his 1963 book than it could have during Lincoln's lifetime. In 1865, Lincoln's eulogists announced that "the foundation of 'our second temple'—a regenerated nation—has been laid in our firstborn." Reverend J.G. Butler explained:

This new birth of freedom was expressed in many ways, but always with emphasis on renewed nationhood: the war "created a feeling of nationality such as never before existed, and our country commences a new career, sanctified by its baptism of blood." America's rebirth involved emancipation, but it cannot be reduced to emancipation. Further reflection cautions the twenty-first-century reader against projecting his or her own perspective on earlier generations. The situation in which Lincoln found himself was the dedication of a cemetery for thousands of young men, many of whom considered racial, religious, and ethnic distinctions morally just. Many of the political officials sharing the platform with Lincoln—particularly state governors 50 representing strong Democratic constituencies—felt similarly; they were pro-Union but indifferent to slavery: Governor Horatio Seymour of New York, Governor Joel Parker of New Jersey, Governor William Denison and former Governor David Tod of Ohio, Governor Augustus Bradford of Maryland, and even Governor Oliver Morton of Indiana. The latter was a staunch Republican, but his presence, no less than that of Democratic governors,' was not lost on Lincoln. He knew that in Indiana, as in Illinois, the 1862 elections created legislatures favoring immediate armistice and repudiation of the Lincoln's emancipation plan. Lincoln also knew that his remarks had to be consistent with Edward Everett's statement, which justified the war as an effort to prevent secession. None of the other ceremonial events—Reverend Dr. Stockton's invocation, Benjamin French's ode, James Percival's dirge, Reverend President Baugh's benediction—implied, let alone mentioned, the issue of emancipation. Did Lincoln alone tell the assembly that its children, assumed to have given their lives to save the country and its democracy, died to free slaves in whose fate they had no interest? Even if one interpretation of Lincoln's intended meaning today seems most compelling, this hardly means that other interpretations are totally wrong. The theme of militancy, for example, had to be part of the Address because ceremony organizer David Will had expressly asked Lincoln for a statement that would strengthen the morale of soldiers in the field. In November 1863—after eleven months of commotion over the Emancipation Proclamation—Lincoln could have written nothing without thinking about slavery. Because secession—the explicit rejection of electoral democracy—was both a necessary and sufficient cause of the war, Lincoln must have thought about it deeply while composing his eulogy for the thousands fallen. On the other hand, the same evidence supporting different interpretations begs the question of how much weight each interpretation carries. The issues raised at the beginning of this essay—whether, in the case of the Gettysburg Address, some generations distort Lincoln's meaning, some generations see part of the truth, or some see more of the truth than others—are now before the reader.  Richard L. Hughes Overview Main Ideas President Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, though only two minutes long, provides an opportunity to explore issues surrounding the American Civil War and the role of historical interpretation. Although Lincoln was asked to provide only a "few appropriate remarks," his commentary on the Civil War has been the subject of frequent historical reinterpretation over the last 145 years. Students of history can examine the text of the Address to debate the meaning of the Civil War at the time and use the popularity of the Gettysburg Address after 1863 to analyze the evolving work of interpretation in shaping historical memory. In engaging the Gettysburg Address and other primary sources as historians, students develop historical empathy and avoid present-mindedness. Connection with the Curriculum This material is appropriate for United States history and United States government classes. These activities may be appropriate for Illinois Learning Standards 16 A3a, 16 A4a, 16 A5a, 16 A3b, 16 A4b, 16 A5b, 16 B4, 16 D4a, 16 D5, 16 D4b, 16 D2c, and 16 B2d. Teaching Level Grades 10-12 Materials for Each Student

Objectives for Each Student

51

Opening the Lesson The students should receive Handout 1 when the narrative is assigned to be read outside of class. Using their United States history textbook and the narrative, each student should complete Handout 1 before class. Developing the Lesson At the beginning of class, the instructor should lead a whole-group discussion of Handout 1 and then introduce the group activity involved with Handout 2. Building upon the questions and discussion associated with Handout 1, four small groups of students should complete the creative assignment in Handout 2. At the end of the class session, the instructor may explain that students may need to finish their design of the $5 bill for homework and that the class will begin the second class session with short presentations of the $5 bills. The instructor should begin the second class session with short presentations of the four designs of the $5 bill as review. Then the instructor should provide a copy of Handout 3 and play the short video clip from the Ken Burns's documentary. The students will then use a dictionary, a textbook, and the text of the Gettysburg Address to complete Handout 3. Concluding the Lesson After students have had enough time to complete Handout 3, the instructor should lead a discussion of the questions with a special emphasis on the relationship between the narrative and the students' conclusions in Question D. Extending the Lesson Handout 4 provides students with an opportunity to analyze the impact of the Gettysburg Address on another famous speech in American history—Reverend Martin Luther King's "I Have a Dream" speech at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. Researching the event and the larger civil rights movement, individual students or small groups can then use their knowledge and creativity to write a television interview that illustrates the link between Lincoln's Address and the modern struggle for racial justice. Assessing the Lesson In addition to collecting the individual and group work involved in Handouts 1-4, the instructor may assign a short essay in which students, as historians of the Gettysburg Address, return to the key questions outlined in the original narrative. Although individual answers may vary, each student should create a historical interpretation that demonstrates his or her understanding of both the narrative and the historical primary sources involved in the lesson. Ideally, the activities will assist students in learning about the Gettysburg Address and understanding the process that generations of Americans continually use to reinterpret the past. 52 Handout 1 Reading Comprehension: Arguments about Lincoln and the Gettysburg Address After reading the narrative "Lincoln at Gettysburg," answer the following questions:

53 Handout 2 Historical Interpretation: The Meaning(s) of the Gettysburg Address The evolution of the Gettysburg Address since 1863 reminds us that each American generation has the opportunity to create its own historical interpretations of individuals and events. Material culture such as monuments, buildings, and money reflect both existing historical interpretations and shape a society's later views of the past. Using the narrative's account of the Gettysburg Address and an American history textbook, redesign the back of the United States $5-dollar bill according to your group's assigned time period. Instead of the Lincoln Memorial, each group should create pictures, short phrases, and symbols of the Gettysburg Address that illustrate the historical interpretation that became popular during your assigned time period.

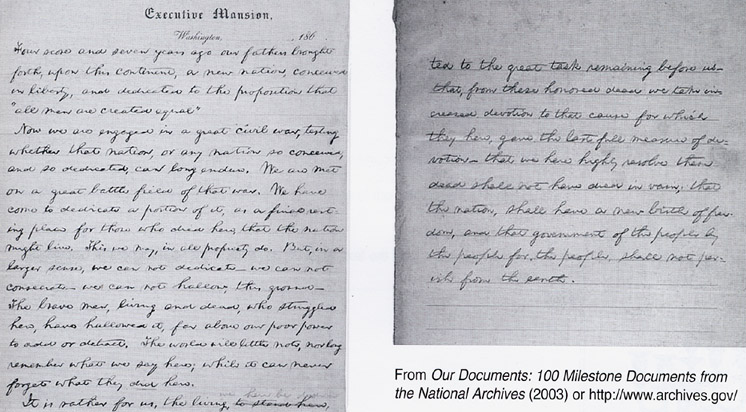

Group A: Create a $5 bill designed in 1863 Why did your group choose these images, words, and symbols to represent a particular historical interpretation? Be prepared to present your design to the class. 54 Handout 3 Analysis: Historical Sources and Creating Your Own Historical Interpretation The history of Lincoln's Gettysburg Address demonstrates the power of words and ideas as each generation of Americans struggles with the challenges of its era. When Lincoln wrote the Gettysburg Address in 1863, he was well aware of the words and ideas that inspired the Founding Fathers and their importance to his audience during the Civil War. 1. Now that you have read the included narrative on Lincoln and the Gettysburg Address, you should examine another secondary historical source—a short video clip entitled "A New Birth of Freedom" in Ken Burns' documentary "The Civil War" (5:48 minutes long in Episode 5, Chapter 10). Then read the text of the Gettysburg Address in Lincoln's handwriting or a typed transcription of it.  Abraham Lincoln, Gettysburg Address, November 19,1863 Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, upon this continent, a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that "all men are created equal." Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived, and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of it, as a final resting place for those who died here, that the nation might 55 live. This we may, in all propriety do. But in a larger sense, we can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow, this ground — The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have hallowed it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, while it can never forget what they did here. It is rather for us the living, here be dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that, from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they here, gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve these dead shall not have died in vain; 2. Use a dictionary to define the following words from the Address: a. Proposition (n.) b. Propriety (n.) c. Consecrate (v.) d. Hallow (v.) 3. Now that you have read the text, what do you think is the meaning of the Gettysburg Address?

56 4. After reading the Gettysburg Address, compare Lincoln's nine sentences in 1863 to the first two paragraphs of the Declaration of Independence.

57 5. Of course, Lincoln wrote the Address in 1863, not 1776. A historian must evaluate the Address within the context of the time.

Taking into consideration your information in boxes A, B, and C, complete the last box below. Edward Everett, a former United States senator and the main speaker at the dedication of the cemetery at Gettysburg, wrote President Lincoln the following day and complimented his short speech for summarizing the "central idea of the occasion" in only two minutes. As a historian who has read the Address and explored other sources, what do you think Lincoln meant when he wrote the Gettysburg Address? What do you think President Lincoln believed was the "central idea" of his speech, the occasion, and the American Civil War on that day in 1863?

58 Handout 4

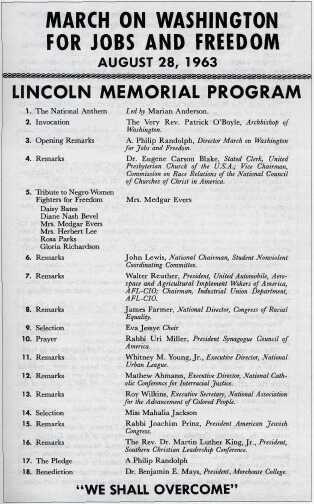

Extending the Lesson: The Meanings of the Gettysburg Address in the Modern Era The history of the Gettysburg Address after 1863 suggests that Lincoln was quite wrong when he declared in the Address that "the world will little note, nor long remember what we say here." For example, Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech, presented in front of the Lincoln Memorial a hundred years after the Gettysburg Address, reflected the continued importance of both the Declaration of Independence and the Gettysburg Address in shaping the modern struggle for civil rights.

Each student should research the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963, and read both the text of King's famous speech and the official program of the event. Unlike Lincoln's speech in 1863, hundreds of television reporters and cameras covered King's speech. After conducting some independent research, each student should write the script of a short television interview with a historian who attended the event. Your interview should explain how King's speech earlier that day reflected the ideas of the Declaration of Independence and the Gettysburg Address. You should also include your opinion as a historian as to why King chose to use particular words and ideas from the American past. In other words, how did King in 1963 create a historical interpretation of the Gettysburg Address and the American Civil War? From Our Documents: 100 Milestone Documents from the National Archives (2003) or http://www.archives.gov/ 59 Television News Interview with Journalist David Brinkley

David Brinkley: Good Evening from Washington. Tonight I am talking with___________, a scholar of United States history who attended today's March on Washington and witnessed Dr. King's moving speech on civil rights. Can you give your thoughts on the speech as a historian? 60 |

|

|