|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

Paul M. Zall As a professional public speaker, Lincoln cultivated the broad spectrum of humor from simple puns and slashing sarcasm to comical stories. Jokes and funny stories, basic tools for preachers and teachers, too, were part of the rhetoric curriculum. Pupils progressed from witty sayings to humorous fables, then to stories memorized and finally impersonated—all adapted to topic, purpose, and especially audience. As consummate communicator on the stump or on the platform, Lincoln adapted humor to audiences of all kinds and classes. The media, friends, and foes credited him with hundreds of stories. Lincoln was not sure how many of them he actually told; at one time he calculated about half a dozen. Later, he said, "about half—and still later, "about one-sixth." Even those he acknowledged were not original. He was, as he said, a retailer. His stories came from newspapers and popular books and were already familiar to his listeners—like the reply of the son when told he ought to take a wife: "Whose?"

Almost every Lincoln story can be traced to some contemporary source or analogue. The famous response to a complaint about Grant's drinking whiskey—"Find out the brand and give it to my other generals"—morphed from an earlier one about King George's reply to complaints that General Wolfe was mad: "Have him bite my other generals." Originality was no issue. It's a basic principle of communication: Don't tell people anything 100 per cent new. Relate it to something they already know. Another basic principle of communication: You don't use the same language when applying for a job as when quitting it. In debate, Lincoln's wit had power to make grown men cry. He cauterized Stephen A. Douglas's idea of popular sovereignty as thin as homeopathic soup made from the shadow of a chicken. Douglas said he never feared Lincoln's arguments, but his stories were like a whack on the back. In other circumstances mere hints would suffice. Lawyer Lincoln merely told the jury that his "opponents had their facts absolutely right but were drawing the wrong conclusion." The jury laughed and gave him their votes for mentioning the punch line of a popular story: "Pa, pa, the hired man and sis are in the hay 61

mow and she's lifting up her skirts and he's letting down his pants and thy're afixin' to pee on the hay." "Son, you got your facts absolutely right, but you're drawing the wrong conclusion." Except in attack mode, Lincoln's humor of choice consisted of adapting stories, such as parables, to make a point. Douglas's political dilemma reminded Lincoln of the old woman in the buggy whose horse ran away with her: "She trusted in Providence till the britchen [britching] broke; and then she didn't know what on airth to do." His choice of parable-like humor made sense to a people familiar with the Bible, as he was. John Hay said Lincoln's humor derived from his "wonderful intuitive knowledge" of people that came from his having risen through all classes from outhouse to White House. They shared the real significance of a prairie mother's calm remark when a baby down in the meadow squawled: "Thar's one of 'em ain't dead yit." His accent and appearance also helped. He and his audiences shared a passion for comical writers like Artemus Ward. Reporters complained it was impossible to render Lincoln's Kentucky accent—"meester chairman, "agin," "unly." But because writers like Ward used comical misspelling and fractured dialect, Lincoln sounded as familiar as the farmer boasting that his scarecrow was so ugly the crows brought back the corn they stole last year.

Fellow congressmen at first saw Lincoln as the quintessential wild westerner. They laughed as he paced the aisles, doing the motions of the old-style elocutionists: "I know that the great volcano at Washington, aroused and directed by the evil spirit that reigns there, is belching forth the lava of political corruption." But by New Year's, they were calling him "the champion story-teller in the Capitol." When Lincoln went north to New England, he upset Bostonian expectations. Yankees were expecting western "stories and high flavored allusions," but in ten days of speaking he gave them only sly remarks. One compared pseudo-Whigs' platform to the peddler's pants "large enough for any man, small enough for any boy." Reviewers agreed that he argued with "sobriety to suit cultured audiences." Veteran newspaper correspondent Henry Villard marveled at Lincoln's talent for adapting to "rough looking farmers ... sleek and pert commercial travelers, staid merchants, sharp politicians." He had learned the hard way after trying to address Wisconsin State Fair folks on the abstract topic, "Man," only to watch them wander off to the cow pens.

At the crucial Cooper Union lecture, Mason Brayman from back home in Illinois was astonished at his old friend's performance in the big city. He saw "a man who at home talks in so familiar a way, walking up and down, swaying about, swinging his arms, bobbing forward, telling droll stories and laughing at them himself, here in New York standing up stiff and straight"—and being serious. On the stump or platform, chameleon Lincoln took on the coloration of his surroundings. His audience came to consist of a mass class of newspaper readers, and the press exploited his earlier reputation as a wild and funny guy. Davy Crockett Almanacs became Old Abe Almanacs. Caricatures of Uncle Sam started wearing Abe's stovepipe hat. And he became tarred with old jokes: "How old is that tree, Abe?" "I'm just about to axe it." Honest Abe's Songster begat Honest Abe's Jokes which begat Old Abe's Jokes which begat Old Abe Joker even though as president he almost never told a joke. Lincoln endured fools. "I have endured a great deal of ridicule without much malice, and have received a great deal of kindness, not quite free from ridicule. I am used to it." Even before the inauguration, Vanity Fair complained that Lincoln's newfound gravitas had created a vacuum of jokes by and about the new president. The press rushed in to fill 62

the vacuum from a bottomless stock of old jokes and new ones from both friends and foes. Old pal Jesse Fell particularly supplied the kind of humor Lincoln enjoyed with close friends, like the way the British cured constipation during the Revolution by hanging Ethan Allen's picture in the privy. Much worse were such disgusting "confessions" as one about how Lincoln first met his future wife in an outhouse. Critics overseas pounced on Lincoln's "flatulent and indecent stories" as mirroring degenerate morals and the mind of "an illiterate boor." At home the press was less shocked that Lincoln told such stories as that friends would print them. He had once explained why he used humor—"Common people are more easily influenced by a broad and humorous illustration than in any other way." Now he explained the new gravitas. "I am . . . talking to the country, and I have to be mighty careful." He developed an aversion to writing that would "furnish new grounds for misunderstanding." Humor feeds on misunderstanding, mistaking, or misinterpreting words, behavior, manners, morals, images, or ideas. Being understood was not enough; Lincoln had to avoid being misunderstood, and so he suppressed his sense of humor. But not entirely. Lincoln's irrepressible wit went bubbling on through private letters and conversation. He told a man seeking a favor, that he had as much chance of succeeding as of sleeping with his wife. Reading a wire from a general date-lined, "From headquarters in the saddle," he said, "He's got his headquarters where his hindquarters ought to be." And his situation reminded him of a neighbor trying to mount a fidgety horse: "If you're getting on, I'm getting off." In the most serious days Lincoln took the presidency seriously, not himself. The skills honed on the stump had made him an uncommon common man. The press anointed him the comical voice of the people. They say he overheard two ladies on the train: "Jefferson Davis is bound to win—he's a praying man." "Well, so's Abram a praying man." "Yes, but God will think Abram's joking." CURRICULUM MATERIALS Lynn R. Nelson Overview Main Ideas One of the most perceptive insights regarding Abraham Lincoln's humor—whether he was telling a long elaborate story or responding to some comment in a few sentences—is the observation by Benjamin P. Thomas, "His (Abraham Lincoln's) ideas moved, as the beasts entered Noah's Ark, in pairs." Lincoln's humor paired a person or event with a principle or idea. To what degree does much of a good story or joke reflect on an individual's ability to couple a particular person, idea, or event with a general principle? This applies equally to both the knowledge and skills of storyteller and the knowledge of the audience. The two activities outlined below involve students in examining the humor, ideas and principles of Abraham Lincoln. The first article engages students in research to examine Abraham Lincoln's description of popular sovereignty as "homeopathic soup." The task seems deceptively simple; however, as students unpack the meaning of this phrase, they encounter much deeper levels of meaning in the historical antecedents of this phrase. The second activity engages students in historical research and analysis as they profile Abraham Lincoln's character through his humor. Students are subjected to frustrations similar to those of the historian who wants more information before drawing conclusions. Both activities are open-ended, and the students are encouraged to consult resources beyond those contained in the activities.

Connection with the Curriculum Teaching Level Objectives for Each Student

63 Activity 1 — Popular Sovereignty and Principle

Opening the Lesson Lincoln said of Stephen Douglas' principle of popular sovereignty:

If you were among the listeners to Abraham Lincoln and Senator Stephen A. Douglas, how would you have interpreted the humor? 1. Write down your interpretation of Lincoln's criticism of popular sovereignty.

Developing the Lesson Perhaps the first bit of additional information is the definition of homeopathic. You may have deduced that Abraham Lincoln believes popular sovereignty is a principle similar to thin soup, but what is the nature of a homeopathic concoction? Homeopathy was a practice of medicine devised by German physician Samuel Hahnemann in the early nineteenth-century. Homeopathy's chief principles were that like cures like; and that a drug's effect is enhanced by dilution. Thus a drug that in large doses would make a healthy individual ill is given to an ill person after a series of dilutions to treat his/her symptoms. There is no scientific evidence that the theory of homeopathy is valid. 2. What does this definition add to your understanding of Lincoln's humor? How is extension of slavery into the territories like a homeopathic cure? Perhaps a reading of this excerpt from the Quincy debate will add to your understanding of the differences separating Lincoln and Douglas. The following paragraphs from the Quincy debate provide more information regarding popular sovereignty's connection with a homeopathic remedy. Please read the following section carefully and reconsider your understanding of the joke. "Judge Douglas also makes the declaration that I say the Democrats are bound by the Dred Scott decision, while the Republicans are not. In the sense in which he argues, I never said it; but I will tell you what I have said and what I do not hesitate to repeat to-day. I have said that, as the Democrats believe that decision to be correct, and that the extension of slavery is affirmed in the National Constitution, they are bound to support it as such; and I will tell you here that General Jackson (President Andrew Jackson) once said each man was bound to support the Constitution, "as he understood it." Now, Judge Douglas understands the Constitution according to the Dred Scott decision, and he is bound to support it as he understands it. I understand it another way, and therefore I am bound to support it in the way in which I understand it. And as Judge Douglas believes that decision to be correct, I will remake that argument if I have time to do so. Let me talk to some gentleman down there among you who looks me in the face. We will say you are a member of the territorial legislature, and, like Judge Douglas, you believe that the right to take and hold slaves there is a constitutional right. The first thing you do is to swear you will support the Constitution and all rights guaranteed therein; that you will, whenever your neighbor needs your legislation to support his constitutional rights, not withhold that legislation. If you withhold that necessary legislation for the support of the Constitution and constitutional rights, do you not commit perjury? I ask every sensible man if that is not so? That is undoubtedly just so, say what you please. Now, that is precisely what Judge Douglas says - that this is a constitutional 64 right. Does the judge mean to say that the territorial legislature in legislating may, by withholding necessary laws or by passing unfriendly laws, nullify that constitutional right? Does he mean to say that? Does he mean to ignore the proposition, so long and well established in law, that what you cannot do directly, you cannot do indirectly? Does he mean that? The truth about the matter is this: Judge Douglas has sung paeligans to his "popular sovereignty" doctrine until his Supreme Court, cooperating with him, has squatted his squatter sovereignty out. But he will keep up this species of humbuggery about squatter sovereignty. He has at last invented this sort of do-nothing sovereignty —that the people may exclude slavery by a sort of "sovereignty" that is exercised by doing nothing at all. Is not that running his popular sovereignty down awfully? Has it not got down as thin as the homeopathic soup that was made by boiling the shadow of a pigeon that had starved to death? But at last, when it is brought to the test of close reasoning, there is not even that thin decoction of it left. It is a presumption impossible in the domain of thought. It is precisely no other than the putting of that most unphilosophical proposition, that two bodies can occupy the same space at the same time. 3. Now you are in a better position to laugh along with Lincoln's supporters or cringe if you are a supporter of Stephen Douglas. What is your understanding of the connection between popular sovereignty and a homeopathic cure? What argument does Abraham Lincoln make about Senator Douglas's interpretation of the extension of slavery into new territories? Which new political party claimed the allegiance of Abraham Lincoln? Which political party had Stephen Douglas been affiliated throughout his political career? The final step is your preparation to interpret Abraham Lincoln's homeopathic humor as a well-read citizen of 1858 might interpret it. Please read the following documents that provide historical foundation for Lincoln's comment on Popular Sovereignty. Article1 Section. 9 of the Constitution of the United States The Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the Year one thousand eight hundred and eight, but a Tax or duty may be imposed on such Importation, not exceeding ten dollars for each Person.

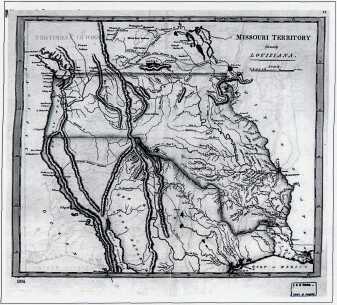

Missouri territory formerly Louisiana. In an effort to preserve the balance of power in Congress between slave and free states, the Missouri Compromise was passed in 1820 admitting Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state. Furthermore, with the exception of Missouri, this law prohibited slavery in the Louisiana Territory north of the 36° 30' 65

latitude line. In 1854, the Missouri Compromise was repealed by the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Three years later the Missouri Compromise was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in the Dred Scott decision, which ruled that Congress did not have the authority to prohibit slavery in the territories. Library of Congress Web Site The Kansas-Nebraska Act repealed the Missouri Compromise, allowing slavery in the territory north of the 36° 30' latitude. Introduced by Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois, the Kansas-Nebraska Act stipulated that the issue of slavery would be decided by the residents of each territory, a concept known as popular sovereignty. After the bill passed on May 30, 1854, violence erupted in Kansas between pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers, a prelude to the Civil War. The Supreme Court decision Dred Scott v. Sanford was issued on March 6,1857. Delivered by Chief Justice Roger Taney, this opinion declared that slaves were not citizens of the United States and could not sue in federal courts. In addition, this decision declared that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional and that Congress did not have the authority to prohibit slavery in the territories. The Dred Scott decision was overturned by the 13th and 14th Amendments to the Constitution. Abraham Lincoln's response regarding the Dred Scott Decision In a speech at Springfield, Illinois, June 26, 1857, Lincoln referred to the decision of Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, of the United States Supreme Court, in the Dred Scott case, in this manner: "The Chief justice does not directly assert, but plainly assumes as a fact, that the public estimate of the black man is more favorable now than it was in the days of the Revolution.

"In those days, by common consent, the spread of the black man's bondage in the new countries was prohibited; but now Congress decides that it will not continue the prohibition, and the Supreme Court decides that it could not if it would. "In those days, our Declaration of Independence was held sacred by all, and thought to include all; but now, to aid in making the bondage of the negro universal and eternal, it is assailed and sneered at, and constructed and hawked at, and torn, till, if its framers could rise from their graves, they could not at all recognize it. 66

"All the powers of earth seem combining against the slave; Mammon is after him, ambition follows, philosophy follows, and the theology of the day is fast joining the cry." What are the reasons why Abraham Lincoln opposes the Dred Scott decision? What constitutional principles does he believe were violated by the decision? Concluding the Lesson 4. Now that you are a very well-informed citizen of 1858. In several paragraphs explain Abraham Lincoln's pairing of popular sovereignty with a homeopathic cure. Be prepared to discuss your interpretation of Abraham Lincoln's view of popular sovereignty with your classmates. Extending the Lesson If you are interested in further exploring the differences separating Lincoln and Douglas, there are a number of resources on-line and in print that will enrich your understanding of the principles that animated the actions of these two great citizens of Illinois. Two comprehensive sources of primary and secondary sources to initiate your historical research are the web site of the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency and The American Memory Collection in the Library of Congress. You may want additional information on such issues as the Compromise of 1850 or Senator Douglas's desire to make Chicago a railroad hub; if so, simply log on to 67 Activity 2 — Profiling a President

Opening the Lesson Our second activity unites two very similar, fascinating activities: crime scene profiling and historical research. Millions of Americans have viewed the various television programs that chronicle the fictional efforts of crime-scene investigators to reconstruct contemporary events from fragmentary and often contradictory events. Ratings of the three CSI programs indicate that all three variations—Las Vegas, Miami, and New York—are consistently among the most watched programs on television. If you add in similar programs, such as Cold Case, you discover that criminal investigation programs dominate popular television. Historical investigation is very similar to a crime-scene investigation in that there is seldom sufficient evidence to satisfy the investigator—detective or historian. Additionally, the historian faces the challenge of very cold evidence—decades or even millennia. Our challenge in this activity is to reconstruct some of Abraham Lincoln's principles from his humor. Remember the initial quote regarding Lincoln in this essay, "His (Abraham Lincoln's) ideas moved, as the beasts entered Noah's Ark, in pairs." The initial activity had you investigate the pairing of homeopathic soup with Abraham Lincoln's opposition to the extension of slavery into the territories as made possible in the doctrine of popular sovereignty. This second activity asks you to profile Lincoln's personality through his humor and the stories told about him. The difficulties you face are even greater than a contemporary CSI: many stories that have been attributed to Abraham Lincoln were not told by him, many stories told by others about Lincoln are not true, and all of the witnesses are deceased. Additionally, your job is not to determine the person who committed a crime, but to profile the principles that Abraham Lincoln chose to guide his decisions. What are principles? They are more elusive than determining who is the perpetrator of a crime. Principles are the values and ideals that an individual or a democratic society uses to guide individual and collective decisions and actions. For example, Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas differed on the principle of popular sovereignty and the extension of slavery. Lincoln opposed the extension of slavery as a matter of principle and would later end slavery through the Emancipation Proclamation. Stephen Douglas's actions were animated by other principles; he sought to lessen the heat of a national debate over slavery by moving the debate to territorial legislatures where the decision could be made by the will of the citizens. His actions were also a product of ambition for Chicago, not New Orleans, to become the major terminus for transcontinental railroads to the west. The railroad would greatly enhance the prosperity of Chicago and the state of Illinois he represented in the U. S. Senate. Finally, Douglas had the ambition to become president, and he believed popular sovereignty would greatly increase his chances of achieving this ambition. How would we profile Douglas's principles from this very scanty evidence? He was ambitious, but he also appears to value democracy. One could argue that he honestly believed that his doctrine of popular sovereignty would remove the slavery issue from the combustible atmosphere of Washington to the cooler political climes of the territories. When the principle of popular sovereignty was enacted in the form of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, Douglas's view of the future violence of 1856 was not much different than our current predictions of the future in 2010; the fog of the future is fairly thick in 1854 and 2008. With the aid of additional sources (evidence) we could arrive at a more informed decision regarding the principles that motivated Douglas. Was it respect for democracy, the desire to avoid violence, political ambition, or some combination of these principles that motivated his advocacy for popular sovereignty? Now we turn our attention to Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln's life was played out in a nineteenth-century frontier where storytelling and humor were greatly valued and admired. As a circuit-riding attorney in Illinois and as a youth growing up in Indiana and Illinois, Lincoln had numerous opportunities to hear stories. Nineteenth-century Americans on the frontier found ways to entertain themselves before the television, iPod, and cell phone came to define contemporary life. Abraham Lincoln defined himself as a "retail" seller of stories. By this he meant that he should not get credit for creating stories, but he simply passed along stories that 68 he believed merited the retelling. Consider the stories told by your best friends. Many of these stories are "retail," but they tell you a great deal about the values of the retail story teller. Are the stories always about them? Are jokes usually aimed at the weaknesses and mistakes of others? Do they ever laugh at themselves? Developing the Lesson Please read the following stories and summarize your thoughts in the chart at the end of lesson. Because there are a number of stories, you should complete a section of the chart as you finish each story. The stories that follow are attributed to Abraham Lincoln. Before the Presidency

Mrs. Goings was a woman who Abraham Lincoln represented in Woodford County. Mrs. Goings had been indicted for the murder of her husband, in spite of high feeling in favor of her; for her deceased husband had been a man of violent temper and her action had had all of the characteristics of self-defense. During the course of the preliminary proceedings, Mrs. Goings' absence was noted and Lincoln was questioned as to her whereabouts. He said he did not know where she might be, but had seen her shortly before, in the courthouse, where she had asked him where she could get a drink of water. Lincoln stated that he did not know, but had always heard that the waters of Tennessee were as fine as anywhere!

Mr. Roland Diller, who was one of Mr. Lincoln's neighbors in Springfield, tells the following: I was called to the door one day by the cries of children in the street, and there was Mr. Lincoln, striding by with two of his boys, both of whom were wailing aloud, 'Why, Mr. Lincoln, what's the matter with the boys?' I asked. 'Just what's the matter with the whole world,' Lincoln replied. 'I've got three walnuts, and each wants two.'

Which historical events does the escaping horse symbolize? What economic principle is illustrated by the walnuts? 69

Presidential Humor Some of Lincoln's friends once warned him that a particular member of his cabinet [Salmon P. Chase] was working behind the president's back in hopes of gathering support for a presidential bid of his own, even though he knew that Lincoln was to be a candidate for re-election. The friends believed that the cabinet officer should either be called upon to refrain from such underhanded tactics or be removed from office. Lincoln mulled over their suggestion, and then he used this story to explain why he wouldn't take any action:

Lincoln gazed at his friends before continuing, "If (the cabinet officer) has a Presidential chin-fly biting him, I'm not going to knock it off, if it will only make his department go." "Biting Flies", www.anglefire.com/my/abrahamlincoln/Humor.html. Benjamin P. Thomas, Lincoln's Humor and Other Essays, 6-7. The stories of Salmon P. Chase and the chin-fly deals with ambition and getting work done. What other examples from history can you find where a president had to decide whether to keep an ambitious and effective rival in office? What role did Chase play in Lincoln's cabinet? What other example of individuals with a "chin-fly" can you think of? What happened to Chase? Could Lincoln continue to control Chase's ambition throughout the war? Lincoln sent a delegation to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton with orders to grant their request. The delegation returned to Lincoln with the message that not only had Stanton failed to follow Lincoln's orders, but had called Lincoln "a fool" for issuing them. Lincoln responded; "Well, I guess I had better go over and see Stanton about this. Stanton is usually right." What does this say about President Lincoln's view of Stanton? With a bit of additional research you could see if Lincoln's perception of Stanton is shared by others. http://www.abrahamlincoln.org/ Self Deprecating Humor Lincoln was not averse to telling jokes about himself. He told the following story on several occasions. The story concerns an encounter with a man while riding a train.

Benjamin P. Thomas, Lincoln's Humor and Other Essays, 12. 70

Lincoln's Observations on Union Generals Lincoln had a low tolerance for Union generals who inflated their accomplishments and bragged about what they would do to the enemy next time they met. One of these very generals had just been badly defeated by the Confederates, and Lincoln related this story to those who were present: "He (the general) reminds me of the fellow who owned a dog which, he claimed, loved to fight wolves. The dog's owner said that his animal spent its entire day tracking down and killing wolves. "One day a group of the dog-owner's friends organized a hunting party and invited the dog-owner and the dog to go with them. They soon noticed that the dog-owner was not excited about joining them. He said he had a business engagement, which greatly amused the others, who all knew that the man was so lazy that he would never have any reason to have a 'business engagement.' They ridiculed him to a point where he had no choice but to go along. "The dog, on the other hand, was excited to be going out into the woods, and the hunting party was soon on its way. Wolves were in abundance, and it wasn't long before a pack was discovered. The dog saw the ferocious animals about the same time the wolves spotted him, and the chase was on. The hunting party followed on horseback. "The wolves and dog soon were out of sight, but the party followed the sounds of the chase. Soon they arrived at a farmhouse, where a farmer stood leaning against his gate. 'Did you see anything of a wolf-dog and a pack of wolves around here?' he was asked. 'Yep,' he replied. 'How were they going?' came the next question. 'Purty fast,'he answered. 'What was their position when you last saw them?' 'Well,' replied the farmer, The dog was a just a little bit ahead.'

"'Now, gentlemen, said the President to his visitors, that's exactly where you'll find most of these bragging generals when they get into a fight with the enemy.'" General George McClellan showed little respect for Lincoln. He frequently kept Lincoln waiting while he finished conversations with other individuals. This disrespect was so evident that even McClellan's staff seemed embarrassed by it, and it often drew comments from newspaper reporters. The president was finally asked about it. Humbly, Lincoln stated that McClellan's disrespect was not a problem with him, if the slow-moving general would just initiate a battle. "I'll even hold McClellan's horse," the President said, "If he will only bring us some success." Lincoln thought highly of McClellan's ability as an organizer, but he was impatient with his hesitancy to attack the Confederacy. If you were President Lincoln, how would you have reacted to General McClellan's criticism of you in the following letter?

71

Lincoln's Comment on McClellan

"If General McClellan isn't going to use his army, I'd like to borrow it for a time." (Commenting on General McClellan's lack of aggression, 1862)

How could President Lincoln have written 250,000 passes to Richmond? Who received these passes and why have they failed to arrive in Richmond? Which early battles of the Civil War could President Lincoln be comparing to "shoveling fleas" and general inaction of the Union Army? Which battle led to the dismissal of General McClellan by President Lincoln? Historians have observed that McClellan was very popular with the troops who served under his command. Why was he popular with his troops? Which Union generals proved willing to fight Confederate troops? During World War I the United States military newspaper Stars and Stripes reported the following often-repeated comment regarding General Grant (February 8,1918).

Which battles and campaigns contrast the performance of General Grant with other generals, such as McClellan, Burnside and Hooker? On Slavery "Whenever I hear anyone arguing for slavery I feel a strong impulse to see it tried on him personally." (Speech to 140th Indiana Volunteers, March 17,1865) What ethical principle is the president expressing in this speech to the Indiana Volunteers? Is he consistent with his earlier position regarding popular sovereignty? BEWARE OF THE TAIL. After the issue of the Emancipation Proclamation, Governor Morgan, of New York, was at the White House one day, when the president said:

72

On the End of the War

If we were able to interview President Lincoln, do you believe he would want to punish the South for secession and the war? What principle does the President express in this story? "PUBLIC HANGMAN" FOR THE UNITED STATES A certain United States Senator, who believed that every man who believed in secession should be hanged, asked the President what he intended to do when the War was over. 'Reconstruct the machinery of this Government,' quickly replied Lincoln. 'You are certainly crazy,' was the Senator's heated response. 'You talk as if treason was not henceforth to be made odious, but that the traitors, cutthroats and authors of this War should not only go unpunished, but receive encouragement to repeat their treason with impunity! They should be hanged higher than Haman, sir! Yes, higher than any malefactor the world has ever known!' The President was entirely unmoved, but, after a moment's pause, put a question which all but drove his visitor insane. 'Now, Senator, suppose that when this hanging arrangement has been agreed upon, you accept the post of Chief Executioner. If you will take the office, I will make you a brigadier general and Public Hangman for the United States. That would just about suit you, wouldn't it?' 'I am a gentleman, sir,' returned the Senator, 'and I certainly thought you knew me better 73

than to believe me capable of doing such dirty work. You are jesting, Mr. President.'

What principles seem implicit in President Lincoln's argument with the senator? What beliefs regarding himself and Confederates support the position of the senator? If you were eavesdropping on this conversation, whose argument seems most persuasive to you? Are President Lincoln's beliefs regarding the equality of men (women?) shared by most American's in the 1860s? Consider specific historical events and ideas to support your answer. This final story is different from the previous stories in two ways: it is about President Lincoln and only a brief phrase expresses his thoughts and it is not humorous. However, since our historical research involves profiling the principles that guided Abraham Lincoln's action this final recollection by Dr. Walker should prove valuable to our task. The Doctor Learns a Lesson The speaker is Dr. Jerome Walker, of Brooklyn, who was showing President Lincoln through the hospital at City Point.

At this juncture in our historical research and presidential profiling you should have many questions and some conclusions. You can pursue your questions on a number of web sites and print resources that your teachers and historical societies will recommend. However, it is time for you and your partner to develop some conclusion about the principles that gave direction to Abraham Lincoln's decisions and actions. This is a very difficult task for a number of reasons. First, Lincoln, as with all persons is not completely consistent in the application of his principles. For example, Abraham is strongly wedded to constitutional principles regarding popular sovereignty, but the rule of law seems less important to him in the case of the self-made widow. Second, the humor and other comments span a number of years—some peaceful years as a young attorney riding the circuit and some as president during a bloody war. Third, there is not enough evidence: a situation facing historians and crime scene investigators. Assessing the Lesson Step II. In your historical research, compare your chart with that of your partner or a small 74 group of students and write a profile of President Lincoln. Your profile will consist of an introductory paragraph, three paragraphs of analysis, and your conclusion. Your profile includes both your conclusions and the evidence supporting your conclusion. For example the jackknife story provides evidence that Abraham Lincoln was able to laugh at himself and may not have been as self-centered as some of his cabinet members and generals. For additional information you may need to add to your store of information by doing on-line searches to provide additional historical information (evidence) needed to profile Lincoln. Concluding the Lesson The following chart should help you and your fellow investigator. Each of you will complete your own chart as you read through the stories about Abraham Lincoln. Compare your tentative findings.

Extending the Lesson Now it is your turn to determine the direction of your research. You may attempt to verify the stories included in this lesson. Lincoln biographers agree that many stories attributed to Abraham Lincoln were changed over time or simply told by others, not Lincoln. You may choose to read Lincoln biographies to better understand this great man. 75 |

|

|