|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

G • R • O • W • T • H

The Illinois and Michigan Canal and the Growth Ronald S. Vasile The idea for a canal that would connect the waters of Lake Michigan with those of the Illinois River (hence the name Illinois and Michigan Canal) dates back to the earliest recorded Illinois history. In 1673 French fur traders, led by Louis Jolliet, came down from what is now Canada via the Great Lakes in order to explore the heart of North America. Seeking an outlet to the ocean, they traveled down the Mississippi River as far as present-day Louisiana. On their return trip, coming back up the Mississippi River via the Illinois River, Native Americans showed them a shortcut enabling them to connect to the Great Lakes via a system of prairie rivers. Jolliet saw that a short canal would join the Mississippi River ("The Father of the Waters") with the Great Lakes. He wrote his superiors that he had found "a very great and important advantage which will hardly be believed." The dream of such a passageway animated every vision and underlaid every plan for what would come to be known as Illinois. In fact, Illinois might be a very different place if not for the idea of the canal. As legislation was being drafted to make Illinois the twenty-first state, in 1818, an amendment was introduced to move the state's northern boundary forty-one miles north. Part of the rationale was to give the young state a port on Lake Michigan, which would allow the state to control the proposed canal from the lake to the Illinois River. Try to imagine Illinois without the Chicago metropolitan area. Wisconsin later tried to claim this land, to no avail. Since the birth of the new nation, American leaders had recognized the urgent need for a network of "internal improvements" to ease the problem of continental transportation. One aspect of Henry Clay's "American System" envisioned a string of canals and roads that would connect the new nation, lessening sectional differences by making different parts of the country interdependent. The success of the Erie Canal, completed in 1825, marked a period of intensive canal building in the United States. Indeed, the years from 1790 to1850 have been characterized as the Canal Era. With the exception of the Erie Canal, most United States history textbooks overlook the story of America's canals, choosing instead to focus on the railroads as the prime force behind America's development in the nineteenth century. In order to assist Illinois in making the canal a reality, in 1827 the federal government gave the State of Illinois nearly three hundred thousand acres of prime farmland, from the mouth of the Chicago River to what is now La Salle, Illinois. The proceeds from the sale of this land were to finance construction of the canal. Buying and selling of canal lands led to rampant speculation, especially in Chicago, the eastern terminus of the proposed canal. Many of the buyers were from New York, Massachusetts, and other eastern states. Noted statesman Daniel Webster, who helped broker the Compromise of 1850, bought canal land near La Salle, and for a time his son Fletcher lived in La Salle County. Thus, in addition to overseeing construction of the canal, the I and M Canal Commissioners also served as land agents and town planners. Few today are aware of it, but Chicago is by definition a canal town, as the first plat of the city was laid out in 1830 by the I and M Canal Commission. Other communities created by the Canal Commissioners include Ottawa, the county seat for La Salle County; Lockport, headquarters of the Canal Commissioners; La Salle, the western terminus of the canal; and Morris, the Grundy County seat, laid out jointly by the county commissioners and the canal commissioners. The other towns along the line of the canal were founded by private interests. 2

The digging of the canal was Illinois' first major public works project, and like many such projects it had a long, controversial history. The ceremonial first shovelful of dirt was turned over on the Fourth of July, 1836, in Bridgeport, then a suburb of Chicago. It may have been a sign of things to come that the day ended in a riot, as Irish construction workers who were not invited to the ceremony pelted dignitaries with rocks, leading to a general melee. There were numerous obstacles to be overcome in digging the canal. The canal was dug entirely by hand, mostly by Irish immigrants. However, Swedes, Norwegians, and French Canadians were also among the work crews. Canal work was shunned by all but those who had limited options. Working conditions were horrible. Autumnal fevers (malaria) disabled and killed workers, as did diseases such as typhus and dysentery. Poisonous massasauga rattlesnakes posed a threat, and in the summer, heat and high humidity made work unbearable, as did mosquitoes and biting flies. In marshy areas leeches covered the skin of canal diggers. The wetlands were breeding grounds for disease-carrying mosquitoes. Some immigrants believed that the digging of the canal, especially through wet areas, released dangerous gases from the ground, thus causing illness. Diggers often worked 12 to 14 hours a day, six days a week, for which they were paid a dollar a day. Many workers demanded to have whiskey included as part of their provisions on the grounds that the alcohol was medicinal and would protect them from fevers and other illnesses. Although it was against the rules, contractors had no choice but to dole out a gill (4 ounces) of whiskey to each man per day. Laborers and their families often lived in utter squalor. One contemporary commentator said of an Irish shantytown near Utica that "a more repulsive scene we had not for a long time beheld. . . The number of persons congregated here were about 200, including men, women, and children, and these were crowded together in 14 or 15 log huts, temporarily erected for their shelter. . . I never saw anything approaching to the scene before us, in dirtiness and disorder. . . whisky and tobacco seemed the chief delights of the men; and of the women and children, no language could give an adequate idea of their filthy condition, in garments and person." Pulling no punches, the writer, journalist James Buckingham, stated that the Irish were "not merely ignorant and poor—which might be their misfortune rather than their fault—but they are drunken, dirty, indolent, and riotous, so as to be the objects of dislike and fear to all in whose neighborhood they congregate in large numbers." This type of virulent prejudice against the Irish was typical of the period. The Irish were subjected to mistreatment for many reasons. Their sheer numbers, especially after the exodus caused by the Great Potato famine of the 1840s, frightened some Americans. Their Catholicism posed a threat to Protestants, who were It took twelve years to complete construction on the I and M Canal. A year after digging had begun, the country was hit by a nationwide economic depression (the Panic of 1837) that slowed land sales. By 1840 the State of Illinois was virtually bankrupt, as spending on railroads and the canal had thrown the state into debt. Work on the canal largely ceased until 1845, when investors from New York, England, and France put up $1.6 million to finish the job. Thus, few events in Chicago's history were more eagerly anticipated than the opening of the Illinois and Michigan Canal. Opened for business in April 1848, the canal ran 96 miles, from the Chicago suburb of Bridgeport to La Salle, Illinois. In order to navigate the 140-foot-drop in elevation between the termini, seventeen locks were needed. Four feeder canals supplied the water, and several aqueducts carried the canal over rivers. Sixty feet 3

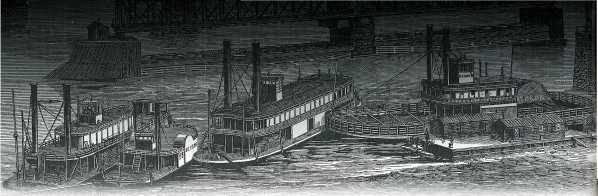

wide and six feet deep, the canal could float boats carrying up to 150 tons. The canal was open from late March or early April until late November or early December. The changes wrought by the canal were immediate and profound. By connecting Lake Michigan to the Illinois River, the I and M extended the water highway that the Erie Canal created from New York to the Great Lakes at Buffalo. People could now cross the Great Lakes to Chicago, take the I and M Canal to La Salle, and then transfer to steamboats for the voyage down the Illinois River to the Mississippi River. In an era when water was the most efficient way to move people and bulk goods, the I and M Canal created a transportation corridor that made trade possible all the way from New York to New Orleans. The canal opened the floodgates to an influx of new commodities, new people, and new ideas. The I and M, and the railroad and highway lines that soon paralleled its connection between Chicago and La Salle, became the great passageway to the American West. At a stroke, the opening of the Illinois and Michigan Canal gave Illinois the key to mastery of the American mid-continent. The opening of the canal signaled the end of northeastern Illinois' days as the frontier and helped transform it to a gateway to the West. The canal also siphoned off trade from St. Louis, one of the factors that allowed Chicago to surge ahead of its chief commercial rival. The canal stimulated the development of new industries. The digging of limestone, coal, sand, and gravel shifted into high gear, as the canal made it economically feasible to quarry and ship large quantities to fast growing Chicago. Mining those resources fueled northeastern Illinois' rapid industrial growth in the nineteenth century. The city of La Salle boomed, as coal mining led to the development of a zinc-smelting plant. Joliet and Lemont provided limestone for buildings throughout the corridor. Exploiting these natural resources in turn spurred new industries, especially the manufacture of glass, bricks, hydraulic cement, and zinc. The proximity of plentiful supplies of coal and limestone played a key role in the success of Joliet's iron and steel industry.

Abraham Lincoln, a longtime supporter of the I and M, trumpeted the beneficial effects of the I and M Canal in 1848 on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives. While acknowledging that the I and M Canal was entirely within the confines of one state (Illinois), he noted that its benefits extended far beyond those borders, reducing the cost of transporting goods, thus benefiting both buyers and sellers. "Nothing is so local as not to be of some general benefit," wrote the future president. "[T]he benefits of an improvement are by no means confined to the particular locality of the improvement itself." For the first five years of its existence the I and M also served as a means of travel for thousands of passengers. The trip from Chicago to La Salle took anywhere from 17 to 24 hours. During the years of the California Gold Rush many emigrants traveled part of the journey on the I and M Canal. Improved travel had a down side, as it also allowed diseases to spread more quickly across the continent. The 1849 cholera epidemic arrived in Chicago via infected passengers from the I and M Canal. By 1853 the Chicago and Rock Island Railroad paralleled the canal's route. Trains could run year-round and were faster, and they quickly took away the canal's passenger traffic. However, the canal continued to prosper in the shipping of bulk goods, and competition provided by the canal kept railroad freight rates lower, a boon to consumers and producers. The canal was also seen as a more democratic form of commerce, as anyone with the means could register a boat and do business on the canal, whereas the railroads were a monopoly. The canal remained the least expensive way to ship bulk cargo such as grain, coal, lumber, and stone. A distinctive canal culture emerged along 4 the line. Boat captains and crews were a rough and tumble lot, as crews were often chosen based on their fighting ability rather than their navigational prowess. The teenaged boys who led the mules down the towpath had a well-deserved reputation for swearing, fighting, and stealing, and the American Sunday School union warned parents to keep their sons away from the canal. The most famous mule driver on the I and M, James Butler Hickok, better known as Wild Bill, engaged in the first fight in his career on the I and M. Locktenders, usually accompanied by their families, were on duty twenty-four hours a day, locking as many as thirty boats through in a single day. Enterprising locktenders also ran side businesses that catered to the canal trade—one ran a tailor business, allowing customers to drop off clothes and pick them up on their return trip. Until he was caught, another locktender supplemented his $300 per year income by working with a counterfeiting ring. The I and M played an important role in the Civil War. With the lower Mississippi in Confederate hands, much of the North's trade came through the canal and the Great Lakes, thus hurting Chicago's rival city St. Louis. The importance of the canal is underscored by the fact that in 1863 the Confederates began planning an attack on Great Lakes shipping, with one of the objectives being to burn the locks of the canal at Chicago. The canal again made headlines in 1871. Due to its phenomenal growth, Chicago's infrastructure had failed to keep pace with its population. The city's sewage ended up in the Chicago River, which ran into Lake Michigan— the source of the city's drinking water. Thousands died of waterborne diseases such as cholera and typhoid. To resolve this crisis, the I and M Canal was deepened to reverse the flow of the river, meaning that Chicago's waste would now flow down the I and M Canal. Residents of Morris, Lockport, and other canal towns were not pleased with this present from the city, and some called it divine retribution when just a few months later most of the Chicago burned to the ground in the Great Fire of 1871. Thanks in part to the introduction of steamboats in the 1860s, peak tonnage occurred in 1882, with over one million tons of cargo shipped. However, the I and M was simply too small, and in 1900 a new canal opened, the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, leading to a dramatic decrease in use of the I and M. Despite a brief resurgence during World War I, the canal was limited to mostly recreational boats before finally closing in 1933, with the opening of the Illinois Waterway. It is no exaggeration to say that the construction and operation of the I and M Canal from 1836 to 1933 tells one of the most significant stories in the transportation history of the United States. Much of the benefit from the canal occurred before it opened, as it brought people and Eastern capital to a sleepy town called Chicago. The canal spurred the development of northeastern Illinois and ushered in a new era in trade and travel for the entire nation.  Ronald S. Vasile Overview

Main Ideas The I and M Canal was the final link in a national plan to connect regions of the vast North American continent via waterways. By connecting Lake Michigan to the Illinois River, the I and M extended the water highway that the Erie Canal created from New York to the Great Lakes at Buffalo. Boats could now cross the Great Lakes to Chicago, take the I and M Canal to La Salle, and follow the Illinois to the Mississippi River south to the Gulf of Mexico. In an era when water was the most efficient way to move people and bulky goods, the I and M Canal made shipping possible all the way from New York to New Orleans, and created Chicago as the nation's greatest inland port. From 1848 until 1900 the canal played an important role in the economic landscape of northeastern Illinois. The canal opened up northeastern Illinois to trade with the North and South, and allowed farmers in the Northwest to get their produce to market, thus stimulating the development of agriculture. Many people traveled on the canal as part of their journey west, especially during the California Gold Rush year of 1849. The canal effectively ended Chicago's days as the frontier and made northeastern Illinois the gateway to further westward expansion. In order to fully understand the canal's impact in primary sources, we can look for clues for how the canal affected everyday life. Connection with the Curriculum The I and M Canal ties in with a number of themes taught in U. S. history classes, including westward expansion, transportation, immigration, and urbanization. These activities may be appropriate for the Illinois Learning Standards 15.C.4b; 16.C.4b; and 16.E.5a. 5 Teaching Level Materials for Each Student

Objectives for Each Student

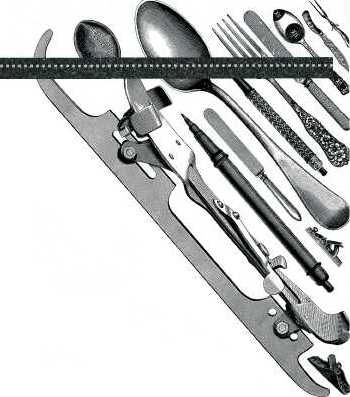

Opening the Lesson Briefly review the previous lessons about the I and M Canal, emphasizing the ways in which the canal molded society in the nineteenth century. Explain that we are going to examine ways in which the canal influenced larger trends in society during the nineteenth century. Developing the Lesson Activity 1 Canal boat names reflected larger events and trends in history, providing important context for the time period being studied. The attached list of canal boat names for the years 1848 to 1870 is from the records of canal boat clearances in the Illinois State Archives in Springfield. For example, the boat George Gaylord was named for a prominent merchant in Lockport, Illinois. He owned a fleet of canal boats and operated a dry-goods store. Divide students into groups and have them research canal boat names. Assign five to seven names to each group. Using the Internet, have each group explain why the names were significant to the time period in question. Each group will develop a poster or PowerPoint presentation and give a report to the class on their boat names. Activity 2 The commodities shipped on the canal were crucial to its success. Hand out the list of tolls for 1851. Have students list items that they are unfamiliar with (Buhr blocks, cordage-rope and string, cooper's ware), or those that surprise them (buffalo and deer skins, marble dust, hemp, manure). Assign students into small groups and using the Internet and or library have each group research three to five of these goods and how they were used in the nineteenth century. Groups will present their finding to the class, and each group will develop visuals to help explain their findings. Example: saleratus is also known as sodium or potassium carbonate, that is, baking soda. It is used as an antacid to neutralize stomach acid, and also reduces odors ands acts as a leavening agent Activity 3 Explain what is meant by the term demographics. Tell students that they are going to use historical census data to help explain patterns of growth. Assign groups of students to chart the growth of the I and M Canal corridor relative to the growth of Illinois. The four main canal corridor counties are Cook, Grundy, Will, and La Salle. Use the website to assess population trends. Students will also chart how Illinois' population density moved steadily northward throughout the century. Information can be displayed in a graph, chart, or other method. Go to: Search each decade between 1830 and 1900 Group 1 will list Illinois' rank among the states in terms of population between 1830 and 1900 Group 2 will find the top 10 counties in Illinois in terms of population between 1830 and 1900 Group 3 will show the ranking of the 4 corridor communities in Illinois between the years 1830 and 1900 Each group will present its findings to the class, with an emphasis on extrapolating general trends. For example, have students note the explosive growth of Cook County, which did not exist in 1830 and became Illinois' most populous county by 1850. Also note how Illinois' population shifted northward during the nineteenth century. 6

Information can be shared as part of a bar graph, chart, etc. Using an overhead, show an Illinois counties map to illustrate how the population of northeastern Illinois boomed after 1830, due in part to the canal. Concluding the Lesson Guide a group discussion of the various activities. For the first activity, have students explain the significance of their boat names and how they reflected the time period in question. Explain that the canal was very much a product of its times and that these boat names give a valuable context regarding the canal era. Topics to discuss include Bleeding Kansas, the Civil War, popular culture, the Gold Rush, and the Mexican-American War. For the second activity, expand upon student information and further explain these items, as well as giving information on items that might not have been covered by students. For the third activity, make sure that important population trends have been illuminated for the county, state, and federal level. Extending the Lesson Activity 1. Have students imagine that a new canal is opening through their town. Have them brainstorm canal boat names that reflect current events. Activity 2. Have students brainstorm a list of goods that might be shipped by water today in Illinois. You could also have a student look up the definition of the word mill. Ask students how they think the term is being used in the handout "Tolls upon the Illinois and Michigan Canal." Explain that a mill is a term used in accounting and is the equivalent of one-tenth of a cent. Have them calculate the total expense of shipping five items the entire length of the canal (96) miles. This activity has many cross-curricular possibilities, especially with chemistry, biology, etc. Activity 3. Brainstorm other reasons why people came to northeastern Illinois—jobs in factories, purchase of state land along the canal, tired of farm life, Assessing the Lesson Activity 1. Assess student learning through the group presentations, posters, and class discussion. Activity 2. Students have adequately explained what these items were, how they were used, and how they contributed to the economy and everyday life. Explanations should include whether we still use the item today; whether it has been replaced by something; and if so, what it has been replaced by. Activity 3. Student presentations will show the rapid development of northeastern Illinois beginning in 1840 and lasting until 1900. 7

8

Make a list of goods shipped on the I and M Canal and how they were used.

9

List reasons that people came to northeastern Illinois.

10 |

|

|