By HENRY J.HYDE

U. S. Representative from the sixth

district, composed of Cook County

suburbs west of Chicago and a portion

of DuPage County, he served in the

Illinois House of Representatives from

1967 to 1974 and was majority leader

(Republican) in the 1971-72 sessions.

Elected to Congress in 1974, he serves on

the Judiciary Committee and the Committee

on Banking, Currency & Housing. He

began his career as a trial lawyer.

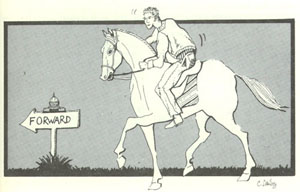

The beggar on horseback: How one congressman views his job

After serving 8 years in the Illinois House with 177 members, now as a member of the U.S. House, 435 members, he finds the differences are more profound than just size. Congressmen, unlike state legislators, are seldom on the floor during debate

EDITOR'S NOTE: Congressman Paul

Simon, Carbondale, a former lieutenant

governor and member of the General Assembly, now a freshman in

Washington, wrote of his impressions of

the national legislature in our August

magazine. Now Congressman Henry

Hyde, Chicago, also a former legislator

and first termer in the nation's capital,

describes his initial reactions. Simon is

a Democrat, Hyde a Republican.

"A BILLION here and a billion

there . . . that can add up to real

money," was the late Senator Everett

Dirksen's classic statement on congressional spending. Dirkson's comment

underscores but one of several factors

that have evoked a sense of awe since I

first climbed the Capitol steps last

January to be sworn in as a freshman congressman.

The massive white Capitol building is

impressive enough, as are the countless

federal buildings housing a teeming

bureaucracy. All these create an aura of

overwhelming size and impregnability

that has a sobering effect on the desire

of new congressmen to change the

world. Although I served an apprenticeship of eight years in the Illinois

House of Representatives, I was still

unprepared for the contrast between an

assembly of 177 House members and a

Congress of 435 members. The differences are more profound than just

the size of the two legislative bodies.

In Springfield, most members are at

their desks when the House is in session and thus, as a captive audience,

they have no choice but to attend debate

and, occasionally, be influenced by it.

But congressmen are seldom "on the

floor" during debate. When the bells

ring in their offices they hurry together

for a quorum call or a vote. One reason

for this seeming indifference to debate

is that members have no desks on the congressional floor, only rows of unassigned seats. No real work can be done

on the floor. Constant attendance

means listening to the many verbalizers

and the too few orators, all speaking for

publication in the Congressional

Record (perhaps because of the

widespread myth among congressmen

that large numbers of people are concerned about and actually read the

Congressional Record).

Mountains of reports to read

In addition, committees will

sometimes meet while the House is in

session or a member may have important visitors in his office, constituents

who have traveled a long and expensive

way to see their congressman. In short,

there are myriad good reasons why he

cannot spend the afternoon on the floor.

The most time-consuming activity,

however, is the most indispensable: reading the mountains of reports and

analyses of legislation sent to members

every day. Besides these, there are

letters and visits from business and

labor leaders, local and state government officials, students and citizens

from every walk of life—the list is

literally endless of those who seek communication with congressmen and

whose messages are important and demand attention and often a response.

Every congressman has a district

population of about half a million people. Increasingly, these citizens seek the

aid of their congressman, and whether

their problem is federal or not, an

answer or some sort of help has to be

provided. The time spent on constituent service consumes a large portion of the time of the congressman and

his staff. The old saying that a congressman is as good as his staff is verified in many ways each day. The staff members' skill at handling people and problems is remarkable.

December 1975 / Illinois Issues / 369

A politician 'must be smart enough to know the game and dumb enough to think what he's doing is important'

In Springfield, a legislator also must

assist the constituents with their "people problems." But state districts are

much smaller and each has three representatives and a state senator to share

the mail and the problems, so there is

really no comparison in the workload

between the two types of offices. The

smaller scale of operations on the state

level makes the state bureaucracy more

accessible and responsive—or so it

seems to me. In Washington the

departmental "runaround" has become

a fine art.

Fiscal policy issues

Freshman congressmen sometimes

feel the excitement of a spectator sitting in the grandstand at the Rose Bowl

game. The big difference is that we

can't just watch the game. Matters of

the highest importance must be studied, understood and finally voted upon.

Most issues have economic, technical,

political and even philosophic implications that the conscientious member

must grasp if he is to vote intelligently

and to be able to defend his vote when

the inevitable criticism surfaces.

One such issue is fiscal policy.

Nowhere in the American political

world is the gulf between Republican

and Democratic philosophies more apparent than in the economic sphere.

Standard Republican doctrine proclaims that inflation, hence recession, is

caused by Congress spending far more

than it receives in taxes. This abhorrence of deficit spending is the root of

all our nation's evils, say Republican

spokesmen over and over again. "Not

so!" reply the florid orators of the majority Democrats, and they proceed to

place all our economic ills at the feet of

Arthur Burns and the Federal Reserve

Board's "tight money" policy. If only

we had a monetary policy that eased

credit restrictions and put more money into circulation we would soon be enjoying the fruits of the New Deal, the Fair

Deal and the Great Society (not to mention Camelot!) in abundance. When it

comes to spending tax dollars we

haven't got, this Congress with its expected $80 billion deficit was anticipated in 1789 by the English poet and

anti-rationalist William Blake, who

wrote, "The Road of Excess leads to the

Palace of Wisdom."

Occasionally some economist will try

to make the point that our inflation / recession is the product of unwise fiscal

and monetary policy plus the

relationship between wages and productivity. But his voice is drowned by the

tumult and shouting of the ideologues

of both parties. The spectacle is at once

stimulating and frustrating.

The issue of energy has consumed

more time, and to less avail, than any

other in Congress. However, even for

one as nontechnical as myself, there is

enormous interest in the many exotic

sources of energy now being hurriedly

funded by Congress. Solar energy is the

new panacea of the liberals, whose mistrust of nuclear energy and whose antipathy to petroleum ("big oil cartels,

obscene profits, environmental hazards,

etc.") and coal ("raping the land, etc.")

has made sun worshipers of them all.

Foreign policy

Watergate provided the impetus for

Congress to declare itself not only a full

partner in the formulation of foreign

policy, but the senior partner. Authors

like Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., who previously had applauded gleefully at every

accretion of executive power from

Roosevelt through Johnson, suddenly

became aware of the specter of the

"Imperial Presidency." Now they write

endlessly of the need to strip the White

House of its heretofore unilateral power

in this sensitive area.

The wisdom of congressional interference in the Soviet Union's emigration policies is still a matter of sharp controversy as is Congress's actions

regarding Cyprus and the ending of the

American presence in South Vietnam.

That we in Congress are subject to shifting political winds in a far more

vulnerable way than is the White House

is a fact not often considered. The

weakening of the Presidency in foreign

policy has emboldened not only

Congress but organized labor as well.

The longshoremen's demand concerning the Soviet grain deal is not likely to

be an isolated occurrence. More and

more segments of society undoubtedly

will seek to "get in the act."

Nevertheless, the resolution of these

issues is vital to the national welfare.

We and our children's children have a

stake in the survival of our country and,

for that matter, in the survival of

Western civilization. No mere word like

"detente" can gloss this over. What exactly are the costs of detente? What are

its consequences in a world grown more

restless and fragmented? Complex questions like these take much of the time

and energy of today's congressmen.

Reform of Congress

The 92 freshmen (75 Democrats and

17 embattled Republicans) all came to

the Hill with an eagerness to make the

94th Congress far better than its

predecessors. The close media coverage

of congressional action has only added

to the determination of the newcomers

to shake things up, to take giant steps

towards that brave new world we

promised our constituents if they would

send us to Washington. There is a sort

of spiritual refreshment in watching

those whose armor is still not dusty or

dented. It is exciting to listen to the

rhetoric of those lately arrived statesmen who are bursting with plans and

programs, which if implemented, will

elevate and deliver us!

But this messianic mission has sputtered and fizzled and finally flopped.

The seniority system, that relic of the

dark ages, was the first totem to be attacked. Three powerful committee

chairmen were toppled, but this was

hardly a major victory, as no new precedent or principle was established. In

these ad hoc situations more was left

undone than was accomplished. My

own view is that the seniority system is

preferable to the brokering of committee chairmanships, a practice that

poisons the political process in

Springfield.

The proclaimed goal of making

Congress more open was only partially

attained, and then only by the Republican House members who voted to

open up their conferences to the press

and public while the Democrats continued to meet in caucus behind closed

doors. In September the Democratic

caucus voted to open their meetings to

the public. Proxy voting in committee

was restored by the Democratic majority,

370 / Illinois Issues / December 1975

hardly a contribution to reform. One

of the more graphic examples of expediency over principle was the silence

of the majority, including 75 freshman

Democrats, while the 83-year-old chairman of the House Rules Committee

personally blocked reconsideration of

the Turkish aid question. As pointed

out by columnist David S. Broder, "He

used the oldest form of arbitrary power

Congress has ever known—the refusal

to call his committee into session." This

action drew no censure from those reformers who would have salivated with

outrage if an old-style Dixiecrat chairman had used this same tactic to prevent consideration of a civil rights bill.

Oh reform, how fleeting and fragile

thou art!

I have always been amused by the

words of Eugene McCarthy, who, in a

memorable display of sour grapes, said

that a politician must be like a football

coach. That is, he must be smart enough

to know the game and dumb enough to

think what he's doing is important. If

anyone fails to perceive the importance

of the substance of politics, he is insensitive indeed. The decisions that must be

made on revenue and spending, the

drawing of the elusive line again and

again between liberty and order, the

protection and enhancement of human

dignity, is hardly unimportant work.

In his last novel, You Can't Go

Home Again, Thomas Wolfe reminds

us that human progress is never in a

straight line. Rather, it is like a beggar

on horseback reeling and lurching. But

the important thing is not that the beggar is drunken or that the horse is

reeling, but that he is on horseback and

he is moving forward. It is the task of

every politician, therefore, to take those

reins and help guide the horse and his

rider towards the justice and liberty we

have been struggling 200 years to attain.

Every elected official knows well the

occupational disabilities of public life.

If your constituents don't question your

integrity and motivation, the media

will. Your pocketbook, contrary to

public opinion, becomes thinner with

each campaign, your family life is all

but shattered and you become a total

stranger to the concept of job security.

In public esteem a politician is rated

19th out of 20 occupations, slightly

above a used-car salesman. Why then,

would a sensible person choose politics

as a career? An obscure Massachusetts

colonial politician named Andrew

Oliver said it best:

|

Politics is the most hazardous of

all professions. There is not

another in which a man can hope

to do so much good to his fellow

creature. Neither is there any in

which, by loss of nerve, he may do

more widespread harm. Nor is

there another in which he may so

easily lose his own soul. Nor is

there another in which positive

and strict veracity is so difficult.

But danger is the inseparable

companion of honor. With all the

temptations and degradation that

beset it, politics is still the noblest career that any man can chose.

|

|

Legislative investigations

The General Assembly should enact "a

code of fair procedures for all [legislative]

investigating groups," and "should include

in its rules a clear statement of the jurisdictions of the standing committees." So contends Charles R. Bernadini in the Chicago Bar Record(March-April 1975) in his article "Legislative Investigations in Illinois; Due Process of Law or Procedural Vacuum?

A Proposal." Bernadini, now a group counsel with the American Hospital Supply

Corp., Chicago, served as legislative assistant to the speaker of the House, 1972-74.

December 1975 / Illinois Issues / 371