BY CONRAD P. RUTKOWSKI:

Associate professor of political science,

Sangamon State University, he earned his

Ph.D. at Fordham University. Rutkowski

is currently a contributing editor to

Illinois Issues.

SECOND ARTICLE IN A THREE-PART SERIES By CONRAD P. RUTKOWSKI

Fogel's 'Justice Model': Stop trying to reform. Punish, but treat all alike

EDITORS' NOTE: This is the second

article in a three-part series dealing with

the Illinois "Justice Model" which is a

package of related proposals aimed at

reforming this state's criminal justice

system. In this article the author

attempts to detail the various components of the plan with particular emphasis

on its most significant parts. The Justice

Model is now available in published

form under the title "... We Are the

Living Proof . . ." from the W. H.

Anderson Publishing Co. of Cincinnati,

Ohio.

THE "Justice Model" of Dr. David

Fogel is an attempt to bring about a

greater degree of compatibility among

the various elements which make up the

entire criminal justice process, particularly as it exists in Illinois. Fogel

intends to accomplish this by discarding

rehabilitation as the philosophy of our

correctional process. The philosophy of

Fogel's plan is to have convicted persons

punished for their crimes by going to

prison, but under a system of equitable

sentences and with a complete revision

of the parole system. Fogel maintains

that this can be accomplished by

eliminating the gross inequities in the

current system, particularly in sentencing and parole. The goal, then, of

this proposed Justice Model is to

establish a greater degree of certainty in

the minds of the public and the criminal

that fixed and precise prison terms will

be served by those who commit crimes.

Fogel maintains that two different

philosophies are operating within our

criminal justice system. In the earlier stages of this system Ś including arrest,

prosecution, and trial Ś a philosophy

exists which holds that an adult offender

is responsible for his own actions and,

accordingly, ought to be held accountable under the law. Fogel calls this the

"volitional model."

Consistent treatment

But during the later stages of the

criminal justice process Ś including

sentencing, prison confinement, and

parole Ś a second philosophy comes

into play. It assumes that the individual

who goes to prison is in some way "sick"

or no longer responsible or volitional,

and that the objective of imprisonment

is to "cure" or "rehabilitate" that person

before he is allowed back into society.

Fogel calls this the "rehabilitation" or

"medical model."

Fogel's Justice Model accepts as a

fact that prisons do not rehabilitate or

cure. He argues that in order for the

correctional part of the criminal justice

process to work, offenders must be

treated during the entire process as

responsible as well as accountable, that

is, volitional. Fogel states this in the

following fashion:

The prison sentence should merely

represent a deprivation of liberty.

All the rights accorded free citizens

but consistent with mass living and

the execution of a sentence restricting the freedom of movement, should

follow a prisoner into prison. The

prisoner is volitional and may therefore choose [rehabilitative] programs

for his own benefit. The state cannot

with any degree of confidence hire

one person to rehabilitate another

unless the latter senses an inadequacy

in himself that he wishes to modify

through services he himself seeks.

In order for the proposed Justice

Model to be implemented, Fogel maintains that a number of significant

changes have to be instituted. The Justice Model involves an entire range

of reform measures, touching upon,

almost every phase of the criminal

justice process. It calls for the reform of:

bail bond procedures; the reform of

grand jury proceedings; the

establishment of a maximum 60-day fair trial

rule; the creation of a new unit within

the Department of Corrections called

the Bureau of Community Safety which

would be responsible for supervising

adult offenders who are not in prisons

the upgrading of court services; revisions

within the juvenile parole

system; and an upgrading of public

defender services. Even so, the most

critical elements of the model involve

the sentencing process and actual

incarceration.

|

Indeterminate sentencing

The current criminal justice system in

Illinois and elsewhere is based on the

principle and practice of indeterminate

sentencing. This simply means that a

judge possesses a very large degree of

discretion when imposing a sentence

upon an individual who has been

properly convicted of a crime. The

General Assembly sets the ranges of

possible prison terms according to the

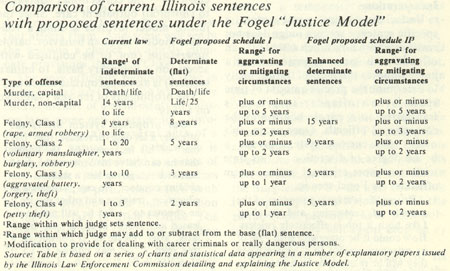

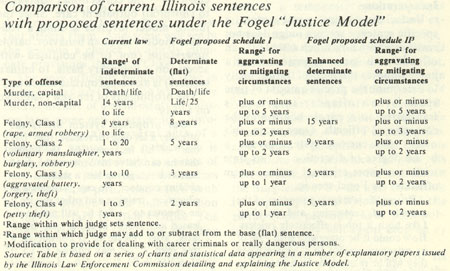

type of crime. Under this system (see

table) a judge is empowered to selects

prison sentence from within a relatively

broad range of periods of imprisonment.

|

14/February 1976/Illinois Issues

Offenders should be treated

as responsible persons, he

argues. At present, they

are considered 'sick'

and the system seeks

to rehabilitate them Ś

often without success

Under exixting statutes, for example, in a non-capital murder case, a

judge is empowered to sentence a

convicted individual to a prison term of

from 14 years to life. This could mean a

prison term of 14 years, 15 years, 16

years, 18 1/2 years, and so on, up to and

including life. Hence, the discretion of

the judge revolves around a rather wide

range of time periods from which he

may select a specific period of imprisonment.

An illustration

Stating it another way, indeterminate

sentencing involves establishing

minimal and maximal penalties, usually

prison sentences. While the goal of the

philosophy underlying this present system

is one of insuring that "the punishment

fits the crime," the result in practice has

been wide disparities in imposing prison sentences even when the

crimes involved were of an identical

nature and of a similar gravity.

To illustrate, assume that two people

have committed the same crime in

different parts of the state. The crime

involved was burglary, which is a Class 2

felony; the crimes were of a similar

gravity. One of the persons is sentenced

to two years in prison, the other to 15

years. An obvious question is: "What

happens when these [felons] share a cell

at Joliet and compare notes? Obviously

the lack of sentencing uniformity Ś in

addition to being manifestly unjust Ś

breeds resentment leading to violence in

our prisons." At least this is the conclusion arrived at by Fogel and his staff

associates at the Illinois Law Enforcement Commission.

In tackling this problem, Fogel is not

proposing that judicial discretion be

eliminated. In fact, it is not discretion

which is really at issue here. Rather,

Fogel is attacking unbridled discretion

Ś discretion which is exercised within

boundary lines that are so far apart that

it becomes unlimited in nature, and for

all practical purposes ceases to be

discretion at all.

Fogel sees the judiciary playing a

crucial and vitally important role in

society's effort to deal effectively with

crime and criminals. In an effort to

assist the courts in fulfilling this role,

Fogel would establish a system of

determinate or "flat" sentences which

would be imposed for specific crimes.

The exercise of discretion on the part of

the judiciary would remain intact, but it

would be of a much narrower nature.

The table compares the present statutory ranges of prison terms for specific

types of crimes to Fogel's proposed

determinant or flat sentences for the

same crimes. The flat sentences listed in

the table are Fogel's examples of how

his proposal could be implemented. The

specific numbers would have to be

debated and determined by the General

Assembly. What is most important to

Fogel is that the range of sentences be narrowed.

Assuming an individual is convicted

of a Class 2 felony, the judge would be

empowered, according to Fogel's "proposed determinate sentences" to impose

a sentence of five years in prison (see

table). This sentence contrasts starkly

with an indeterminate sentence under

the current system which could range

anywhere from one to 20 years. But

Fogel's reform proposal does not stop

here. It is much more complex and

attempts to address itself to all of the

relevant factors that are involved.

Fogel acknowledges that while different crimes might be identical in nature,

seriousness. It is here where discretion is

called upon to play a role, one which he

defines carefully and with precision.

It is not only possible, but highly

probable, that identical crimes will vary

in their seriousness, that the circumstances

surrounding these acts will

affect how they are judged and weighed.

Some circumstances may tend to

"mitigate" or lessen the degree of assigned

seriousness. In other situations different

circumstances may "aggravate" or

increase the seriousness of the crime in

question. In order to allow for these

differences and at the same time insure

that sentencing for a similar crime is

carried out prudently and equitably,

Fogel's plan would provide for a limited

modification of his proposed "flat"

sentence.

Career criminals

Using the same Class 2 felony as an

example, Fogel's plan would permit a

judge to impose a base prison sentence

of five years, but he could add up to two

years for aggravating circumstances or

subtract two years for mitigating

circumstances. The net result for this one

type of crime would be a prison sentence

ranging from three to seven years,

which varies considerably from the one

to 20 year term under the current

system. But Fogel's plan goes further to

give consideration to "career criminals."

His Justice Model actually proposes

two schedules of flat or determinate

prison terms. The initial schedule with

the lesser, flat prison sentences is

intended to apply largely to non-career

criminals and individuals who do not

constitute a serious threat to society.

In

February 1976/Illinois Issues/15

'A system in which

prisoners "con"

correctional officers

into providing favorable

reports to parole boards'

order to deal effectively with those who

choose to make crime a career or are

genuinely dangerous, the model provides an alternative schedule of "flat"

sentences which Fogel calls "proposed

enhanced determinate sentences" (see

table). Within this category, as in the

straight determinate sentences grouping, provision is made for the exercise of

judicial discretion to allow for aggravating or mitigating circumstances.

Consequently, a career criminal who

was convicted of a Class 2 felony would

be sentenced to nine years in prison, plus

or minus two years.

From all of the preceding discussion it

ought to be apparent by now that Fogel

is addressing himself almost solely to

felony crimes. This is the case simply

because it is primarily in this category

that the greatest degree of discretion and

potential for abuse exists. In terms of

murder, the initial sentence options are

the death penalty or life imprisonment.

With respect to misdemeanors, the

length of the prison stay is so minute as

to not permit abuses of discretion.

Incarceration

Under our current penal system, a

specific sentence set by a judge does not

really establish how much actual time an

offender will spend in prison. Once a

judge imposes a sentence, the authority

to determine the precise amount of time

spent by an offender in prison is

transferred to a parole board and the

correctional officials. Once again, this

means the current system invests a

broad degree of discretion Ś this time

with even more criminal justice system

officials. As Fogel sees it:

Prison life is largely a product of the

anomie of sentencing and paroling.

Like both it too is effectively ruleless.

How could it be otherwise with 95% of

its prisoners unable to calculate when

they will be released or even what, with

a degree of certainty, is demanded of them

for release candidacy by parole authorities?

It is the parole board that determines

when and under what conditions an

individual is released from custody, and

thus it is the parole board that determines how much time an individual

actually spends in prison. Correctional

officials participate in this decision making process by providing parole

boards with reports on prison inmates.

and it ought to be noted that these

reports are largely subjective in nature.

A natural result of this process is a

system in which prisoners "con"

correctional officers into providing

favorable reports to parole boards in order to

insure positive actions on requests for

early release from prison.

A day for a day

The proposed Justice Model attempts

to remedy this situation by providing for

a system whereby an offender can

reduce his sentence by one day for each

day spent in prison without violating

established rules. The offender would

then begin his prison sentence knowing

he could be out of prison in half the

time, if he does not violate any rules. In

order to encourage continuing lawful

and responsible behavior, the offender's

earned good time would become

"vested," not subject to being taken away,

according to Fogel's plan.

If these changes were instituted,

parole Ś at least as we know of it today

Ś would no longer be necessary. Fogel's

plan actually implies the abolition of

parole. Fogel and his associates argue

that "parole supervision is a medical

concept Ś the correctional equivalent

to [hospital] outpatient care. Since the

justice model revolves around a

volitional model of human behavior, parole

supervision (not to be confused with

access, on a voluntary basis, to human

services) is an inappropriate construct."

The proponents of the new system go

on to say:

Our proposed system offers the

offender a set date for release from "day

one" of his incarceration. He knows

that he can halve his sentence by good

behavior . . . giving him a stake in law-

abiding conduct. He can participate in

education, training and other service if

he chooses to Ś but he will not be

released any sooner in either case.

Similarly, after release he is considered a

free man ... he may choose to go it

alone. In short, the proposed system is

impartial, non-discretionary, definite, and volitional.

All of this means that when an individual is

sentenced to prison, he will knowwith

a significant degree of certainty

how much time will actually have to be

served. The time will be fixed and within

certain limits it might be decreased,

but in no event will it be increased.

Parole, pardon board

Notwithstanding all of this, the parole

(and pardon) board itself would not be

done away with. Under the Justice

Model the board would take on a new

and different, meaning with a series of

specific assignments. Firstly, it would be

involved in easing the transition from

the old to the new system by continuing

parole functions for all prison inmates

who were indeterminately sentenced.

Secondly, the board would continue its

traditional decisions for parole of

offenders sentenced under the current

system so that actual time spent in

prison would be compatible with sentences being meted out under the new

flat-time sentencing procedures. Thirdly, the board would serve as a certifying

agent for days of "good time" earned by

offenders so that offenders and the

board would know definitely how many.

days had been vested by each offender.

Finally, it would serve in an advisory,

capacity to the governor in matters

relating to commutations, reprieves, and pardons.

The key elements

There are still other elements of the

criminal justice system which are

proposed for changes in Fogel's Justice

Model, but the proposed changes for

sentencing and imprisonment are the

key components of Foge's plan. These

are the two elements, more than any

others, which attack head-on the twin,

flaws of the present system - unbridled

discretion and uncertainty Ś which

have fostered a multitude of inequities

or injustices. These inequities, in turn,

have fueled fires of discontent, anguish.

despair and rage within our nations

prisons in Fogel's view.

In a very genuine sense Fogel is echoing John, Viscount Morley, in his

work, On Compromise, when he said.

"You have not converted a man because;

you have silenced him."É

Next month: The Justice Model Ś What

are the chances that it will be implement

Illinois?

16/February 1976/Illinois Issues