|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO |

Staff |

Links |

and Illinoisans on welfare say, 'Yes, and please hurry'

Sandra Mendez-Green thought she would be better off when her husband James moved out of their Chicago apartment two years ago. James made good wages as a roofer and carpenter working six to seven days a week, but Sandra says she saw little of the money. He would come home on payday without a pay check, just $50 or $100 in cash and excuses. "My truck broke down," he would say, or, "This is all I made." Sometimes he would go hunting with his cousin without bothering to call her, or would awaken her in the dark hours of the morning, which was sometimes worse. "Our baby had just been born and I was up all night with him," says Sandra. "Plus I have a thyroid condition that made me tired all the time." They tried marriage counseling, but it didn't take. He became verbally abusive. Finally, on his birthday in March 1992, James Green left his wife and five-month-old son Joshua.

Then, like many women, Sandra found life as a single parent to be trying. When she asked James to send money for diapers or for food, he replied, "That's not my responsibility. I'm not living there now." She is two months behind in her rent, has unpaid medical expenses of over $1,000, has not received a penny of child support, scrapes by on take-home pay of $198.42 a week, cannot afford medical care for herself and had her food stamps cut off because welfare caseworkers couldn't count the number of weeks in a month.

|

Like many people, Sandra Mendez-Green has found that the welfare system doesn't help much. It doesn't provide a decent living, secure medical coverage, adequate nutrition, affordable day care, effective child support enforcement or useful help finding a job. Most of the 1.3 million Illinoisans living on public aid find that welfare just doesn't work. Here's why: Welfare is a monthly grant to help meet the basic necessities of living, but listen to Carolyn Miller: "It's pay the light bill or eat. It's pay the rent or eat. It's always either/or." It is food stamps to provide basic nutrition for a family, but listen to Linda Baldwin: "You say, 'Girl, what you got in your pantry; let's get together.' You hook up with a friend and share the dinner. You buy a lot of Jiffy mix and cornbread, starchy foods. You have a lot of Kool-Aid, but it's only halfway sweet because you can't afford the sugar." It is a medical card to ensure that poor people receive health care, but listen to Mendez-Green: "I had terrible headaches. I went to this doctor because he accepts a medical card. I qualified for one month because I had over $ 1,000 in back medical bills. It turned out I had a scratched cornea. It cost $36 for a bottle of eyedrops. I'm supposed to go for a follow-up visit, but now I can't qualify for a medical card because I'm work- |

|

12/February 1994/Illinois Issues

|

ing. I need glasses but I can't afford them. I have a thyroid condition; I get tired. I need an ultrasound to diagnose the condition, but I can't afford it." It is Social Security payments to ensure those with disabilities are cared for, but listen to Crystal Lester, who has had two surgeries on each of her knees and back surgery for a ruptured disc: "Because I'm disabled, I lost a $25,000 a year job, a company car, health benefits. At the beginning of the month, I paid my bills and didn't have money left over for groceries. I made a decision — we have to have food, so I set aside all these bills." It is housing subsidies to give poor people shelter, but listen to Gerri Tyson, who lives in Stateway Gardens, a Chicago Housing Authority project: "They fixed the tub and it quit leaking one day. I have running water in the bathtub nonstop. Water comes from the back of the toilet when you flush. The elevator hasn't worked for two months." |

It is education and training programs like Project Chance that are supposed to help people get jobs. But listen to many who have tried to move from welfare to work.

Mary Hartsfield: "I've had three different jobs — each one not enough to live on."

Roxanne Betke: "I was denied Project Chance because I had an infant rather than a school-age child."

Johnnie Bames: "Project Chance stepped in and said 'Here is $20, go look for 20 jobs.' Hey, bus fare costs $1.80."

What is welfare? It is an income support system that leaves more than a million people in Illinois below the poverty line, a Medicaid system that leaves 1.3 million without health insurance and thousands more underinsured and without adequate care, a housing system that leaves 80,000 people homeless and thousands more in substandard and overpriced housing, a child support enforcement system that can't find deadbeat parents or, when it does, keeps most of the money and a job-creation system that produces not enough jobs, and even fewer jobs that can support a family better than welfare itself.

Carolyn Lee, a single mother raising three children in Springfield, sums it up: "The system is so totally screwed up."

Nobody is more eager to see President Clinton fulfill his campaign pledge "to end welfare as we know it" than those people who receive it. Their stories tell of a system that is degrading, confusing, uncaring and punitive. They tell of living life on the edge — where one mis-step turns progress into defeat, where efforts to better themselves often are stymied by an inscrutable, inflexible and inconsiderate bureaucracy, and where incentives to work are frequently overshadowed by incentives to lie and cheat. "Welfare has but one purpose," laments Carolyn Miller, a Chicago woman who is trying to escape it by opening her own business, "to keep you down."

And so it was that many welfare recipients eagerly testified last August in Chicago before the Working Group on Welfare Reform, Family Support and Independence, the task force Clinton established to examine welfare policies and recommend changes that the president will present to Congress. The Clinton reform proposals will come just six years after Congress approved a sweeping overhaul of the welfare system — the Family Support Act of 1988. That law placed emphasis on education, job training and various support services, such as day care for children and extended health benefits, to give welfare recipients a fair shot at learning a job skill and making the transition from welfare to work. The law mandated that each state create a JOBS (for Job Opportunity and Basic Skills) program to ease that transition, and Congress set aside $1 billion as matching funds for states to use in helping welfare recipients find work.

Though the Family Support Act is barely in early childhood, the head of the president's task force opened a hearing in Chicago last August by announcing the administration's "objective is to create a new system, a way for people to regain control of their lives." David Ellwood, an assistant secretary at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and co-chair of the working group, said four themes would drive the

February 1994/Illinois Issues/13

welfare reform proposals:

• "Work ought to pay," Ellwood said. "If you work, you shouldn't be poor"

• Child support enforcement should be improved dramatically.

• Education, job-training and other services should be employed to help people get off and stay off welfare.

• A two-year time limit should be imposed for receiving welfare benefits, which Ellwood acknowledged was "the most controversial" aspect of the working group's endeavor. Still, he insisted, "welfare shouldn't go on forever."

Ellwood said the working group's investigations revealed a welfare system that had left recipients "alienated, frustrated, humiliated — people with a powerful motivation to work but who have lost their dignity. We have heard story after story of a welfare system that actually puts barrier after barrier before them."

And then a parade of welfare recipients told the task force tale after tale of why welfare doesn't work. At the hearing and in interviews elsewhere, welfare recipients shared a conviction voiced by Carolyn Lee, a recipient in Springfield: "There's no way you can get ahead on public aid. It's not meant for that."

First, welfare doesn't pay. Uniformly, welfare recipients who testified before the working group or were interviewed by Illinois Issues say that public aid grants and other income support (such as food stamps) are so niggardly that they are forced to live in substandard housing, scrounge for food, juggle monthly bills, go without medical care and even cheat the system to get by.

Roxanne Betke, a 25-year-old high school graduate, told the Clinton task force that she had left her husband after seven years of an abusive marriage. "My husband got the car and a paycheck; I got the kids and evicted," she said. After months of fighting eviction notices, lost records at welfare offices and changing caseworkers, Betke said she began "to question my decision to trade one form of abuse for another."

|

When, after five months of battling for benefits, she received her first welfare grant, she discovered it didn't go very far. Her grant was $408 a month, not counting food stamps. "I can't afford to buy diapers. We have electricity because someone else pays for it. We have a phone because a friend pays the bill. I pay $550 for a two-bedroom apartment that we share with mice and bugs; I pay $400 and work off the rest picking up trash. Alcohol bottles and condoms lay in the stairwell. I'm on so many waiting lists for public housing it isn't funny. The homeless go to the top of the list. I hope we go to the top of the list when we're homeless."

Despite complaints about public housing — the dangers of housing projects and the poor upkeep — many recipients are grateful for the housing because it saves them money and because the alternative is usually worse. Linda Baldwin rented an apartment in Chicago's private housing market and recalls that the water from the hot-water tap came in two temperatures: "It was either boiling hot or cold enough to drink." When she moved to public housing, she says, "we had heat, no mice, and the kids didn't have to go to bed with their coats on." Mary Hartsfield, like Baldwin a single mother from Chicago, calls public housing "a blessing, even though some projects are deplorable." In the private |

|

Indeed, it is easy to understand what Gerri Tyson means when, asked what it takes to survive on welfare, she answers, "It takes a magician."

Here's why:

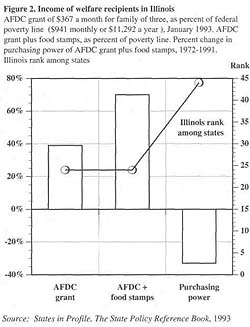

The typical welfare family in Illinois — a family receiving a monthly grant through Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) — has a mother and two children (more than two-thirds of those receiving AFDC are children). A family of three with no other income is eligible for an AFDC grant of $367 a month plus $285 in food stamps, a total of $652 month-

14/February 1994/Illinois Issues

ly or about $7,800 a year. That amounts to just 68 percent of the federal poverty line — $11,523 in 1993. But a family that earned just 40 percent of the federal poverty line — about $4,400 in wages — was not even eligible for an AFDC grant, although it could qualify for food stamps.

One of those families belongs to Sandra Mendez-Green, who knows about performing magic with money. Last August she received a letter from the Department of Public Aid informing her that her food stamp allotment of $158 a month was to be terminated in September; the reason: "Your income has increased." Except, her income had not increased;

July had an extra payday, making it appear that her monthly income had gone up. "I'll have to dip into our rent money for food because we lost our food stamps," she says.

|

Yet, that was not even the chief of her worries or frustrations. She was more concerned about becoming homeless again, losing the apartment where she and her two-year-old son, Joshua, live in Chicago's "Six Corners" neighborhood on the northwest side because the house had been sold and she could not afford the increase in rent. Because she has a part-time job, she does not receive an AFDC grant. Yet, her weekly take-home pay of $198.42 does not even stretch to cover her current rent of $380 a month. She also has a letter from her landlord notifying her that she is $1,010 delinquent on her rent payments. Those are not her only backlog of bills. She has a letter from a collection agency showing delinquent debt of $1,403 in medical expenses. When her parents took Joshua to the hospital for a polio shot, Mendez-Green says, "They told my mom, 'If your daughter doesn't pay her back bills, we'll deny service.'" Joshua is covered by a public aid medical card, but her income disqualifies Mendez-Green from coverage. Instead, she has what the Public Aid Department calls a "spend-down," which operates like a monthly deductible, meaning that after Mendez-Green pays $852 a month in medical expenses (more money than she brings home in a month). Public Aid picks up the rest. She has a thyroid condition that makes her fatigued, and she has a letter from a doctor recommending a "thyroid scan to determine the nature of the disease." Says Mendez-Green: "I can't afford it." So it is not hard to see why welfare recipients often feel driven to illegal, and even desperate, measures. "I was getting $414 a month," says one recipient from Chicago. "My rent was $345. That left $65 for lights, gas, phone. I had to sell food stamps to pay those bills. I know it's against the law." A Springfield recipient says she, too, knows people who have sold food stamps, adding that some taverns do a hefty business in trafficking contraband food stamps, bought for 50 cents on the dollar. Almost every recipient has a story about someone they know who cheats the system by earning income without reporting it, typically by taking jobs that pay in cash. Just as common, welfare recipients report, are public aid workers who look the other way. Says Linda Baldwin: "It's like they say: 'Lie to me.'" Christopher Jencks and Kathryn Edin, researchers at Northwestern University, reached the same conclusion from a study of welfare families in Illinois in the late 1980s. In a 1989 arti-

|

|

February 1994/Illinois Issues/15

cle in The American Prospect, Jencks and Edin said low benefit levels "force most welfare recipients to lie and cheat in order to survive." Their conclusion was that the Family Support Act, just then beginning to take effect, would move few mothers off welfare because "single mothers do not turn to welfare because they are pathologically dependent on handouts or unusually reluctant to work. They turn to welfare because they cannot get jobs that pay any better than welfare."

Work doesn't pay if you're on welfare. Johnnie Barnes: "When I got a job, I felt I had to notify Public Aid. If I made $100, they took $100. How can I get ahead?"

Linda Baldwin and Gerri Tyson discovered the same dilemma when they each got jobs earning $11,000 annually as "prevention specialists" at Chicago Commons, a west side social service agency that, among other things, tries to help long-term welfare mothers break the cycles of poverty. Baldwin, an ebullient woman, recalls their reaction when they received their first paychecks: "We said, 'Can you believe we're making this much money?' We thought we were rich." So rich, in fact, that they treated themselves to a dinner at Carson's, Chicago's famous rib restaurant.

Then, she recalls, "reality set in." Public Aid pulled the plug on all the welfare benefits that were the life supports for their families. "They discontinued everything I had," says Tyson. "The month after they found out I was working, the check, the food stamps, the medical card all were discontinued. You're supposed to keep a medical card for a year, but I didn't know it and by the time I found out, my year was up." Welfare recipients frequently complain that they are not told about their right to continue such benefits as Medicaid insurance or child care.

Baldwin: "We were right back where we started."

Tyson: "We were worse. We had to pay for carfare, lunches, babysitting. Public Aid said they didn't pay relatives to babysit."

Baldwin and Tyson found out what many low-income people discover: Their choices often are limited to welfare or minimum wage jobs, neither of which is sufficient to sustain a family. "Either AFDC benefits or minimum wage work, even if full time, leaves a family of three far below the poverty line," reports Julie Strawn in a 1993 study of welfare in Illinois. Strawn, now a senior policy analyst with the National Governors' Association, worked for the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities when she prepared the study for the Chicago Jobs Council. "Full-time minimum wage work totals about $8,400 a year, while the poverty line in 1993 for a family of three is estimated to be $11,523," she notes in the study. A minimum wage job will leave the typical single-parent family only slightly better off during the first year off welfare than on, she found. However, after the first year, she reports, "such a family may actually be financially worse off working than on AFDC because transitional health and child care benefits will have expired." Strawn found that of all welfare families that leave public assistance, nearly half return to AFDC within a year and a half, mostly because their low-paying jobs do not provide health insurance and because they cannot find affordable child care.

The problem is threefold. First, the pool of low-skill, good-paying jobs is shrinking in Illinois, as elsewhere. Second, the expanding sector of the state (and national) economy is in service employment, typically with low wages and few benefits. And, third, welfare recipients tend to lack the education and skills needed to qualify for the high-paying service jobs that will support a family above subsistence levels.

Though these problems are serious in medium-sized cities like Springfield or metro areas such as Chicago, they are acute in rural areas of shrinking opportunities and growing poverty. Franklin County in southern Illinois is a prime example. The number of people in Franklin County receiving AFDC rose 72 percent between 1980 and 1992. Even more alarming is the stunning 211 percent increase in food stamp allotments and the 150 percent jump in medical assistance since 1980, trends that Alan Summers, administrator of the Public Aid office in Ben-ton, expects to continue. AFDC caseloads seemed to have plateaued in the last couple of years, Summers says, but he anticipates the demand for medical assistance and food stamps will continue to rise, the consequence of the changed economy of southern Illinois.

Summers notes that Franklin County has historically relied on two industries: farming and coal mining. "People have left farming in droves," he says. "Coal mining, same thing. Fifteen years ago coal mining was still at a relatively high level of hiring. In the last 10 years, mines have closed, laid off lots of people. That's really created a burden." The county's economy today, Summers says, is almost entirely service-oriented; he says it is "a part-time economy without medical assistance." He says the significant increase in food stamp recipients is tied to the part-time nature of the local economy. "With the positions people hold and the hours they work, their income is usually just enough to meet housing expenses and utilities.

"There is a marked contrast in the type of individual you see here today and what you'd have seen 20 years ago. Twenty years ago people who wanted to work could work. That's not true today. A lot of educated, bright individuals have no opportunity or can't go where the opportunity is."

Summers says Public Aid supports job-training programs for welfare recipients at nearby community colleges and says he believes those efforts help make "these people marketable. Unfortunately, southern Illinois doesn't have the economic base it needs to give these people a permanent place in the

16/February 1994/Illinois Issues

economy and the community. We can provide the training but we can't provide the solution — the job."

Even if, as the Clinton task force has promised, the government could make work pay, it still faces obstacles in making work programs work.

"I want to be self-sufficient," Roxanne Betke told the welfare reform task force. But because her three children are under the age of six, Betke is not required to participate in the state's Project Chance welfare-to-work program as are women with older children, who can lose benefits if they refuse to participate. Thus, she was told she had to go on a waiting list to receive job-training assistance. "Who am I, what are my skills, what are my goals — I've never been asked any of those questions," Betke said. "Project Chance is a liability."

Bette Nahas didn't necessarily find state job programs a liability, but she didn't find them much of an asset. When she got divorced she had been out of the work force for nine years, and her job experience consisted mainly of waitressing. "I had no skills, just a GED." She went to the Illinois Job Service, an arm of Project Chance, but found little help. She was told that because she had a child under age six, she wasn't required to participate in a job program. "But," she says, "I wanted to work. I remember that they weren't very helpful." Through a friend, Nahas learned of a teller training

program at the Harris Bank of Chicago. She now has a stable job and has had four promotions in five years. Public Aid welfare-to-work programs played no role in her success. "They never did anything," says Nahas. "Public Aid would never think of going out of their way to find an organization like Harris Bank."

Not everyone is quite as harsh in assessing the state's welfare-to-work program, but praise generally amounts to little more than Mary Hartsfield's qualified compliment: "Project Chance is designed to help, but it's underfunded."

Julie Strawn's study for the Chicago Jobs Council underscored both of these convictions. "Particular components of Project Chance have been effective in placing AFDC clients in jobs," her report stated. "For example, 97 percent of those who completed the job skills/vocational training component found work as did 77 percent of those who completed a post-secondary associate degree program." But she also found that fewer than one in 10 adults receiving AFDC in Illinois was enrolled in Project Chance, and she noted, "Welfare reform in Illinois has been severely constrained by lack of funds." The program quit accepting clients for part of fiscal 1992 and again in January 1993. In fiscal 1992, Illinois claimed just 40 percent

Not only is work unprofitable for welfare recipients, but many also find that they cannot get ahead through child support payments either. Enforcement of child support orders by the Department of Public Aid is so lax that most women collect nothing, and even when the agency does collect child support it keeps most of the money.

"If I left my son, I'd be thrown in jail for abandonment," Sandra Mendez-Green told the welfare task force, "but his father who is making $30,000 and has not paid a penny of child support is not looked on as a criminal." Two things stand out for Mendez-Green from her first visit to the child support divi-

February 1994/Illinois Issues/17

sion of the Public Aid department. "The caseworker laughed at me and wouldn't listen to information about my husband," she says, "And they said they couldn't help me because I wasn't divorced." (She cannot afford a private attorney, but is on a waiting list with a publicly funded legal assistance foundation for representation in divorce proceedings.) But she knew her rights. "Illinois law says you have to give a temporary child support order" when parents are separated, she says. She got an order demanding that her husband pay her $703 a month in child support. "It was set unusually high so he would respond, which he did." His response was a letter with no return address which Public Aid accepted as an appeal that he could not pay because he was homeless. So Mendez-Green appealed. "He didn't show up at the appeal hearing and after that they did nothing. I called and said, 'What's going on with my case?' They said, 'We don't know; you've got an administrative order.'

"But I'm not getting any money," Mendez-Green said. Finally the child support enforcement office discovered that her husband had been working and using his own Social Security number, meaning that all that was needed to collect child support was to withhold an amount from his paycheck. "They told me they didn't know he had been working because their computers were six months behind in tracking people." After all this, she then received a letter from Public Aid informing her that it would close her case unless she provided her husband's Social Security number and other information — even though she had supplied the data during her first visit to the office. "They lose information all the time. A lot of times they get mad when you call, but if I don't call, they don't do anything. So many times I just wanted to give up." Now, two years after her husband walked out of the house, Mendez-Green has yet to receive any child support.

Hers is apparently a common experience. According to the Association for Children for Enforcement of Support (ACES), there were 1.2 million children in Illinois owed $1.3 billion in unpaid child support in 1991, the most recent figures available from state reports submitted to Congress. Nine out of 10 children on welfare are entitled to child support but do not receive regular payments, ACES reports. Debbie Kline, midwest coordinator for the organization, disputes Public Aid's claim that it has a 60 percent collection rate for child support. "That just refers to new cases," says Kline. "And they don't count kids who don't have child support orders. Actually, Illinois has a 9 percent collection rate."

But even when fathers pay child support, welfare recipients find it hard to get ahead. That's because they see little of the money. "My ex-husband has to pay $240 a month in child support," says Carolyn Lee. "I get to keep $50." That's the going rate — Public Aid keeps the rest. "The system is designed to recoup [a welfare recipient's] payments from the man," says Elizabeth Solomon, a former recipient and now an advocate for recipients' rights. "It gives her $50 for reporting him and then reduces her food stamps."

Sandra Mendez-Green speaks for many poor women when she told Clinton's welfare reform task force: "If Joshua were receiving regular child support payments, we wouldn't have to rely on welfare."

Welfare undermines family stability, strips recipients of their dignity and keeps them in the dark about their benefits and rights.

"We'd get more benefits if we separated," Linda Armstrong, a 30-year-old mother of three told the welfare task force. She works full time and her husband works minimum-wage odd jobs when he can find them, but they still live below the poverty line despite a rent-subsidized apartment in public housing. "Public Aid wants to break up families," says Johnnie Bames. "If I get married, they cut me off. What if the husband doesn't have a job? Why can't they support the family until you get a job?"

Others say welfare workers are inconsiderate of family relationships. When Mary Hartsfield told a caseworker she didn't want to work because she feared leaving her children at home, he said her 12-year-old was old enough to "stay home alone." Hartsfield says one son was scared to go to school because of gang violence in the neighborhood. "So I sent him to Iowa to live with a relative and then they cut my check," she recalls. "I thought: when it rains, it pours."

Mostly, recipients say welfare workers are just plain inconsiderate. "He treated me like garbage," Armstrong told the welfare task force of her first encounter with a public aid caseworker. Recipients complain frequently, and bitterly, that the welfare system and the public stigmatize them in ways that not only are demeaning but also debilitating. Armstrong says the caseworker said to her: "Why don't you get a job?" Another recipient, pregnant when she first went to the Public Aid office, says a caseworker greeted her: "Why didn't you wait until you were married?" Another former recipient notes that children often feel stigmatized in school when they participate in free meal programs or miss out on field trips because they cannot afford to go. "Everything the school system does tells these kids they're different," says one mother. Another recipient notes the reaction of employers when they see on job applications where the recipient lives: "The minute they see that public housing address, they throw those papers away." Carolyn Miller says such attitudes carry over to the general public. "Everybody looks at you and assumes they know all about you," she says. "They have no idea you want to have a better life." Letitia Lehmann told the welfare working group she wanted to escape welfare because "I don't want my children to

18/February 1994/Illinois Issues

feel like they're nothing."

But they also find little help, advice or compassion at public aid offices. Mendez-Green tells of arriving at the welfare office at 8:30 one morning, as she had been instructed, only to be told the person she had to see would not be in until after lunch. "What am I supposed to do?" she demanded.

"Why don't you go to the Taste of Chicago?" answered the welfare worker, referring to the city's summer lakefront food festival. "I can't afford the Taste of Chicago," Mendez-Green replied.

Her experience is all too typical. Recipients tell of sitting long hours in crowded waiting rooms, only to be told they didn't bring the proper forms or that records were lost or that appropriate authorities were unavailable. They tell of completing endless forms and paperwork, only to be told they made a mistake and must start all over. "If I make a mistake or another person makes a mistake on the paperwork, my children pay dearly for that," Lehmann said. Others say they learn more about benefits, new programs, job

of the federal funds available to support education, employment and training activities for people trying to escape from welfare, placing it 46th among the states in percentage of federal dollars used. The state lost $30 million in federal funds, Strawn disclosed, because it failed to put up the required matching dollars. Only two states left a higher amount of federal money unclaimed.

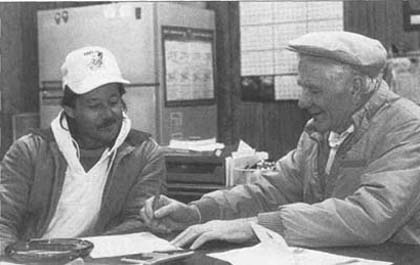

Bill Crocker, supervisor of Goode Township in Franklin County, goes over paper-

work with Earnfare client, Robert Talley (on left). Earnfare is a controversial state

program that replaced General Assistance support for people, mostly single men,

who qualified for no other public aid. There were 83,000 General Assistance recip-

ients when the program was eliminated by the General Assembly in August 1992.

There are now approximately 13,000 people deemed "unemployable" and therefore

eligible to receive monthly grants and limited medical benefits under the state's

Transitional Assistance program. People who are considered employable must work

for their $231-a-month grant and for food stamps. The state pays salaries for six

months for the 3,600 participants in Earnfare. The Public Welfare Coalition recently

called for an overhaul of Earnfare, including higher pay, medical benefits and elimi-

nating the requirement that clients work for food stamps. The Department of Public

Aid calls Earnfare a success in moving clients from welfare to work.Photo by Phil Pearson

opportunities and their rights from other recipients than from welfare workers. "The key with Public Aid," says one former recipient, "is that you have to know exactly what to ask for. You have to get the words just right."

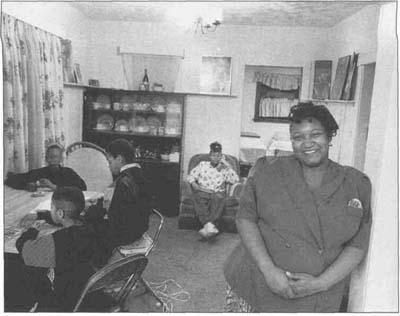

Carolyn Miller with her grandson. "I was determined to get off public aid,"

says Miller, who is planning to open a food catering business. She says wel-

fare recipients are unfairly stereotyped. "Everybody looks at you and assumes

they know all about you. They have no idea you want to live a better life."

Photo by Jon Randolph

Says another: "The system changed me from being courteous to being devious."

So, "ending welfare as we know it" will be no small endeavor. One of the people trying is Robert Wright, acting director of the Department of Public Aid. He also testified before the welfare reform panel in August. He praised his agency as a "long-time leader in developing innovative approaches to improve AFDC programs and services." He outlined several initiatives undertaken by the Edgar administration to plug holes in the state's tattered social safety net. Chief among those is a policy called "Work Pays," instituted last November when federal authorities approved a waiver of existing regulations to let welfare recipients keep $2 of every $3 they earn, the other dollar going to reduce the AFDC grant. For a mother earning about $500 a month from a job, the change would result in an extra $111 a month compared with previous policy.

Wright also described Fresh Start, a collection of demonstration projects that he said were "aimed at removing barriers to employment and family stability and increasing the self-sufficiency of welfare clients." These measures, which also required federal waivers, were designed to remove penalties against two-parent families, encourage recipients to accept temporary or seasonal employment, offer jobs and training to noncustodial fathers, enhance prevention services to teenagers in AFDC families before they become pregnant or drop out of school and increase support for homeless families. Wright also praised his department's record in collecting child support; more than $1 billion collected since the 1970s, he said. "In these times of diminishing resources and escalating need, Illinois continues to explore new avenues of welfare reform through creative programs, waivers and demonstrations," he told the welfare reform working group.

Advocates for low-income people often applaud these steps, though usually for the positive direction they are taking rather than for any significant effect they will have in making the lives of large numbers of poor people better off. They are, after all, quite small steps. Work Pays affects less than 10 percent of the 238,000 AFDC families in Illinois. The demonstration projects are by definition small in scale — 300 families in the homeless assistance effort, 500 youngsters in a youth employment program, 450 fathers in the plan to provide job training to noncustodial parents. "Illinois' waivers are pretty good," says Sandra O'Donnell, a professor at Roosevelt University in Chicago who has studied welfare reform. "But that has been what has passed for 'welfare reform' — grant waivers of failed policies."

Wright concedes as much. "Our obligation to our clients is to provide financial assistance, medical assistance and other social services that, when possible, will allow that client to move from welfare to work.

"The fact that we and every other state have made proposals to change the system reflects the belief that the system is not working the way it ought to work."

Donald Sevener is a Springfield journalist who has written extensively on issues of poverty.

February 1994/Illinois Issues/19

|

|