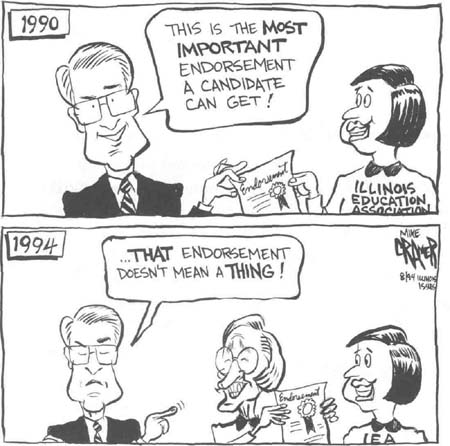

By JENNIFER HALPERIN Not too much, says Jim Edgar. Lots more than it has been, says Dawn Clark Netsch. The outcome may ride on which gubernatorial candidate is best able to articulate a coherent vision of government to voters Think about Dawn Clark Netsch for a moment, and consider the first things that come to mind. She's running for governor of Illinois. She's a Democrat. She wants to raise the state's income tax by 42 percent. Wait a minute — Netsch's tax plan is much more complicated than that. The increase she's proposed in the income tax would mean $1 billion in property tax relief, as well as $1 billion extra for education. Plus half a billion dollars in other tax The fact that most voters probably regard Netsch as more of a tax raiser than tax reformer suggests that her problem is less one of vision than one of leadership relief for middle- and lower-income people. But with just a few weeks left until voters visit the polls, these important details still seem hidden behind the impression that Netsch's chief gubernatorial goal is to sock it to the state's taxpayers. In large part, this impression is due to incumbent Gov. Jim Edgar's largely successful effort to remind voters over and over of the fact and size of Netsch's proposed tax increase, attaching "42 percent tax hike" around her neck like a ball and chain. But what many people may not remember is that four years ago, it was Edgar who wore the tax hike ball and chain. "Ironically, Jim Edgar was in the same position in the beginning of the 1990 campaign," says Doug Whitley, who served as Edgar's revenue director for nearly two years before leaving for Illinois Bell and soon thereafter becoming president of Ameritech Illinois. Edgar had said forthrightly that he favored making permanent a temporary income tax surcharge that was to expire in 1991, a position that opponents Steve Baer in the primary and later Neil Hartigan used to savage him. "Early in his 1990 campaign he opened himself up to that kind of thing — discussion of shifts in the tax structure," says Whitley. "Then Steve Baer and Neil Hartigan tried to put him in a corner on it, so he turned around and made the no-tax-hike pledge." That pledge has helped define Edgar as a governor and his view of government: long on caution, short on grand visions. Now it is Netsch who finds the tax issue a defining symbol of her philosophy and her politics. If Edgar feels comfortable with a myopic view of government's role, Netsch does not. Her tax plan is emblematic of a vision that harbors a more activist approach to government. Yet the fact that most voters probably regard her as more of a tax raiser than tax reformer suggests that her problem is less one of vision than one of leadership. She may be trying to sell tax reform, tax relief and adequate school financing, but voters seem to be buying Jim Edgar's more limited version of what government can or should do. Edgar is the first to acknowledge he's not the big, dramatic, headline-grabbing, fix-everything-all-at-once type of governor. His view of government is more limited than grandiose, more cautious than ambitious, more utilitarian than Utopian. And he doesn't seem overly concerned if people interpret his deliberate approach as a lack of vision. "Lots of people criticize [my administration], saying, 'Where's the vision? Where's the new things?' Well, the problem has been we're trying to sort through the things we have already because we have a lot more than we can afford," he says. "Some people define vision by spending money. When I first took office, we didn't have a lot of money to spend. In many cases, you had to cut severely a lot of programs. It wasn't like you had the option to go out and create any new programs." Edgar has placed much blame for the financial situation he encountered on Gov. James R. Thompson, whose 14 years as Illinois governor preceded Edgar's election. Thompson has been criticized since leaving office for borrowing money to fund large projects — many as part of the touted Build Illinois program — whose bills have yet to come due. "Initially, I think you can say the fault was with the previous administration and the previous legislature,". Edgar said. "They lived beyond their means ... and left a lot of financial time bombs waiting to go off." The economy didn't help matters any, he says. "Revenues just kept going down because the recession continued and got worse when I took office. All the economists were wrong. It wasn't over in May of 1991, or at least we weren't done being impacted; it was more like January or February of 1992." 12/October 1994/Illinois Issues

Even with these financial limitations, Edgar feels he has exhibited leadership and innovation in his own way. "To me, we have shown vision. We did away with General Assistance [for welfare recipients] and replaced it with Earnfare, requiring people to work," he says. "We recognized in education that we have to have more accountability. We've shown a lot of new approaches. But to change things systemwide without getting a chance to perfect them may set the stage for the system to collapse." Edgar sees government as playing a partial role in solving society's problems. For instance, he points to Project Success as a potential problem-solver that was started by government but can be duplicated and expanded by private interests or local communities. Project Success, which has expanded to 54 sites, attempts to use schools to link existing social services with people who need them. For instance, a teacher might identify students' potential social problems and help steer them to services that can help. "If we did a better job steering abused children to abuse services, and hungry children to needed services, we could be of more assistance," he says. "This is an approach we need to see multiplied throughout the state," he adds. "But it takes money every year, and we don't have money to put them all over. Schools can do this themselves, though. And businesses and the public need to get more involved. We need more help outside the schools. "One of the most important things I've seen happen in Project Success is that parents have been getting involved, and that's a step in the right direction. Government can't do everything. The biggest cause of abused and neglected children, for example, is the breakdown of the family structure. I have yet to figure out how government can change that. We're not going to solve every problem. Like with kids killing kids: There's certain short-term ways we can help, like changing a law that says you can't detain juveniles more than 30 days. That's something we can deal with in a law. But government can't solve why an 11-year-old shot a 14-year-old. Maybe communities should be more involved, people in neighborhoods should be serving as mentors, schools should be more attuned to problems." That is Edgar's view of government's role, and he attributes criticism of his administration more to a failure of marketing than a lack of vision. "Our changes may not have a catchy title or package," he says. "Sometimes that's what it takes. Like with Build Illinois — some call it capital projects, some call it pork; Thompson called it Build Illinois and people thought it was brilliant. I'll leave it up to someone else to figure out how we could market what we've done better." October 1994/Illinois Issues/13 Whitley agrees that circumstances have restricted Edgar's ability to undertake large-scale spending projects that many traditionally associate with visionary leadership. "Vision is kind of in the eye of the beholder," he says. "To a great extent, Jim Edgar's first term was dominated by the condition of the state. He made a promise that he was going to get the state's financial house in order and that he wasn't going to raise taxes, and once he set that stake in the ground he had a commitment to hold to it. It limited his ability to move visionary agendas, large projects. "There are people who will take brick-and-mortar projects like highways, stadiums, Comiskey Park, and have those become the agenda-setters. But Jim Edgar wanted a leaner, meaner government. That's an agenda that's much harder to measure ... it's much less sexy." What's more, Whitley says, any money that was available often had to go toward meeting court orders that demanded improvements in the state's departments of Mental Health and Children and Family Services. "He had to keep the budget reined in, but at the same time he had to deal with problems like those at DCFS," he says. "The social ills dictated where the dollars were going to go. How many brick-and-mortar projects can you tout when you have such severe social problems? His vision was more limited and less tangible than more traditional politicians, who often measure services by the number of cornerstones they lay. Jim Edgar didn't promise people the sky; he said he was going to be efficient, and four years ago that's exactly what people wanted to hear." But given the severe social problems Whitley describes, is efficiency enough in measuring gubernatorial success? Some people don't think so.

"I think Edgar has set modest to moderate expectations for

his governorship and style of governing," says Jim Nowlan, a

senior fellow with the University of Illinois' Institute of Government and Public Affairs. "He sincerely sees the office as an

instrument for administration. That's the approach he thinks is

most appropriate. I have not seen

any bold initiatives from him. I've

seen many pilot projects, but I can't

think of any that have gone from

pilot to full-grown programs. To be

fair to him, maybe he sees the office

as a place to make things better

rather than replace what exists with

something new."

To Nowlan, though, a different philosophy may more effectively deal with the state's problems. "Thinking about other governors with different approaches, clearly John Engler of Michigan and Tommy Thompson of Wisconsin stand in sharp contrast," Nowlan says. Engler did away with the use of property taxes to fund education in Michigan, and Thompson pushed large-scale welfare reform in his state. "Even if Edgar wanted to do something like that, his campaign pledge precluded it. Personally, I appreciate the more drastic style of a John Engler because there are dramatic problems out there and we elect chief executives to wrestle with those problems." If Netsch hoped to ride to success on voter annoyance with Edgar's cautious approach to drastic problems, her campaign took a wrong turn somewhere. The first and possibly most crucial problem, as Whitley points out, was in allowing the Edgar campaign to define her. "I think it's important to get up and explain what you want to do," he says. "But you can't have a campaign that has only one issue or is perceived as having just one issue. The public at large doesn't focus on revenues, spending, obligations, available balances, lapse-period spending, or any of the fiscal buzzwords that go over with a financial audience." Nowlan adds: "Edgar has used his money to define Netsch. I assume he's been fairly successful at changing her plan for education and property tax relief into a 42 percent tax increase." And that means voters haven't gotten to know Netsch, or know much about her record of 18 years in the state Senate. Voters may not know that she has been a longtime advocate of measures that would limit the amount of money candidates can spend in a race, and would limit how long campaigns last. That she pushed for a family and medical leave act in Illinois for years before it became federal policy. That she helped push for elimination of the state sales tax on food and medicine, saying it was a regressive tax that hit the elderly and lower-income people particularly hard. And that she helped pass legislation that toughened penalties for sexual crimes against women. Although these causes suggest a public figure with a broad, even visionary, outlook on government's role, it is not Edgar's campaign commercials alone that have obscured Netsch's image in the public mind. Netsch herself has demonstrated scant ability to communicate clearly — whether it comes to telling voters about Edgar's shortcomings or answering questions without a shower of subordinate clauses. These are no small matters in a society where a television advertisement brought her more fame as a pool shark than as a reformer of the Illinois tax structure. Although pithiness may be an overrated quality in a politician incoherence is not a useful trait in a leader. A significant casualty of he communication problem has been the failure to explain to voters how she would spend the extra billion dollars her tax proposal would raise for education. 14/October 1994/Illinois Issues Even with financial limitations, Edgar feels he has exhibited leadership and innovation in his own way "It's not going to be the same in every school," she says. "I have support for year-round schools, longer school days. I think every kid should have access to computers. There are a lot of schools where there's no computer for the kids, while some of the richer schools have two computers per kid. In some schools, they need access to science labs. Others need to be hooked up with long-distance learning. In a lot of places, smaller class size is critical. I don't know what all the needs are — I'm not an educator. Would I know this as governor of Illinois? No. We have to involve more people in the decision- making — people at the local level, at the schools. But it's important to tell them as chief executive of the state that I'll do my part, and the resources will be there." Netsch's inability to articulate a singular vision for the schools and schoolchildren of Illinois — the very cornerstone of her campaign — reflects a larger failure: an inability to sell inherently controversial issues to a skeptical public. It can be perceived as a failure of leadership. If there's anything this campaign has revealed so far, it's that candidates' records as lawmakers and public officials are easily lost amid the search for slick messages that are easy to translate to voters. For example, although Edgar has exploited Netsch's tax proposal for political advantage, a look at his record when he was a state lawmaker in the mid-1970s shows that he

October 1994/Illinois Issues/15 sponsored legislation to allow school districts to adopt an income tax by referendum. His goal was to shift the burden of funding education from property taxes to income taxes. It's easy to interpret such thinking as a willingness on Edgar's part, at least at one point in his political life, to explore the fairness of Illinois' tax structure — an issue Netsch has longed to discuss. Edgar has since distanced himself from consideration of an increase in the state's income tax beyond his push to make permanent the temporary income tax surcharge as he promised in his 1990 campaign for governor. He says his thinking has changed in the last several years because he believes keeping corporate income taxes low will help retain jobs in Illinois. "I'm cautious about an income tax hike and the effect on job creation in the state," he says. The election could have opened up a fruitful debate over tax equity and the fairest way to pay for our state's public schools, if Edgar were willing. Unfortunately, says Nowlan, voter interest is more easily captured with talk about candidates who want to raise taxes, period. Similarly, the campaign might have engaged the question of the growing plight of abused and neglected children in Illinois. When he campaigned for his first term as governor, Edgar said his top human service priority would be the prevention of child abuse. At the time, there were about 18,700 Illinois children in foster care. Today, a record 40,000 Illinois kids are in foster care, and caseworkers at the Department of Children and Family Services have been ordered to work overtime to reduce the enormous backlog of cases. But even this volatile issue hasn't sparked much discussion from the candidates.

At this point, Edgar probably feels the

less said, the better. He may not have garnered a reputation as a visionary leader,

but he's banking on most voters feeling

safer with his cautious style of governing

than with a long-winded activist who has

more faith that government can be an

important and positive force in the lives

of Illinoisans.

|

|||||||||||||||

State Sen. Penny Severns is running for lieutenant governor on the Democratic ticket.

State Sen. Penny Severns is running for lieutenant governor on the Democratic ticket.

Lt. Bob Kustra is once again Gov. Edgar's running mate.

Lt. Bob Kustra is once again Gov. Edgar's running mate.