|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

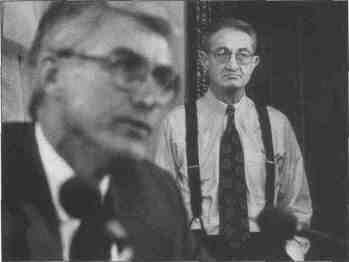

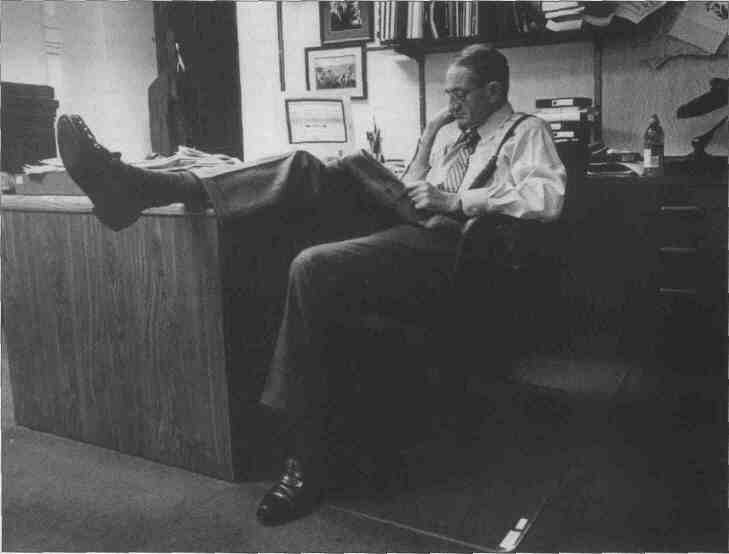

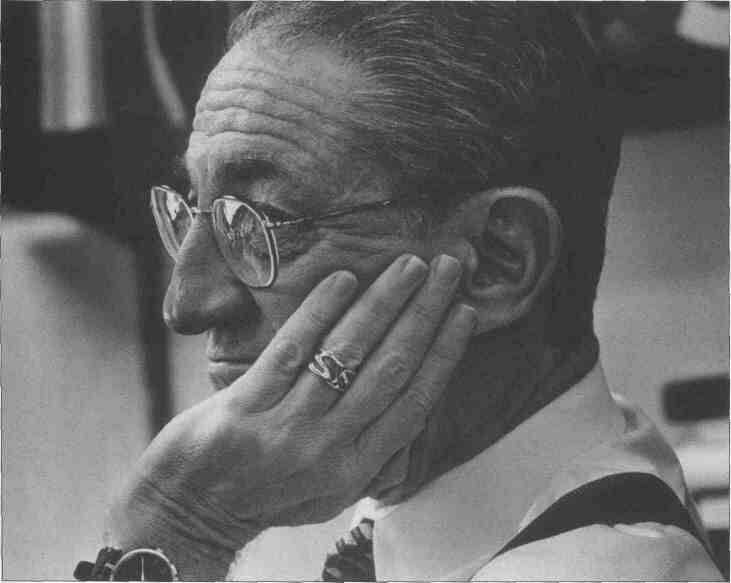

Mike Lawrence, government watchdog, takes his growl and moves on by Donald Sevener Photographs by Judy Lutz Spencer Everybody has a favorite Mike Lawrence story. Here's mine: It's mid-July, 1984, maybe '83. Outside, the heat and humidity seem to have mistaken this for State Fair week, so it's refreshing to stay inside the secluded, air conditioned comfort of the Statehouse pressroom, calmed also by the legislature's recent flight from Springfield. But inside the Lee Enterprises news bureau, the atmosphere is anything but calm and comfortable. Mike Lawrence has a tip and is on the scent of a good story. It seems a man, we'll call him Johnny, has been shafted by the Department of Corrections, which promised him a job, offered him a job at the East Moline Correctional Center, but then reneged in favor of someone with stronger fealty to the Rock Island County Republican organization. The Lee bureau, representing four downstate newspapers, including its flagship Quad City Times in the Rock Island-Moline area, is in battle formation, which mainly means Lawrence is marching back and forth shoes off. brow furrowed, indignation unfurled, intensity at full mast, outrage at the ready in an office so cramped that his long legs can make only two or three strides before he must turn and retrace his steps. He paces when he's uptight, and this is high Richter uptightness: He has called the governor's office, the director of Corrections, the East Moline prison, the Rock Island County Republican headquarters, political sources, good-government sources. He wants answers and he wants them now. No, he wants them yesterday. By press time, he has his answers, and the tale of Johnny being jilted by the Thompson Administration for crass political purposes adorns page one of the next morning's Quad City Times, which styled itself "The Midwest's Most Exciting Newspaper." Ultimately, fried on Lawrence's skillet of public scandal, the administration repents, relents and restores its pro-mise; Johnny gets his job. Another notch in the reputation of Mike Lawrence, government watch-dog. But there is a footnote to the story. Lawrence subsequently gets wind that Johnny has lost his job at East Moline. Indignation rising, he calls the Department of Corrections, where he discovers that Johnny has indeed been fired. Inspired perhaps by the atmosphere around him, Johnny decided to walk off with a television set, property of the state of Illinois. Even the most vigilant watchdog sometimes barks up the wrong tree. More often over the past 30 years, Mike Lawrence's bark and his bite have been a formidable force in Springfield: first, as a journalist exposing wrongdoing and explaining public life in Illinois, and for the past decade, shielding Jim Edgar's image while serving as the ethical conscience of state government. The dreams of most youngsters astronaut, Hollywood, NBA are still illusions. Mike Lawrence, growing up in Galesburg in the early '50s, had already reached the pinnacle of his 20 ¦ May 1997 Illinois Issues

profession. "I owned and ran my own newspaper at age 11," he quips, "and it's been downhill ever since." He had faced up to the reality that he did not possess the skills to fulfill his dream of becoming a professional athlete, so he decided to do the next best thing. "My teachers had told me I did a good job in writing," he says. "I read the sports page every day, and I wanted to become a sports writer." Driven even at that young age, Lawrence set out to achieve his goal. His paper was called the Lawrence Weekly. Being publisher meant also being reporter, writer, typesetter and paper boy. It was before the days of copy machines, so with his typewriter stuffed three-carbons thick, Lawrence pounded away with his aggressive hunt-and-peck style, typing and retyping to deliver a four-page edition to his 20 subscribers. Soon, he became known to neighbors as "Scoop," a nickname that followed him to Springfield. Then he got his first big break in journalism. He worked as public address announcer and official scorer for local baseball games, a job that also took him by the newsroom of the Galesburg Register-Mail to drop off box scores the next morning. One day he decided to ask the sports editor if he could write up accounts of the games. "He let me, and at age 14, I got my first byline." He didn't get paid, but that didn't matter; he got something more valuable than money. "That's where I learned journalism in the newsroom of the Galesburg Register-Mail" he says. "My main assignment was to get lunch every day for the managing editor. By the time I was 15 or 16, I got to the point where, frequently, I'd lay out the sports page, write headlines." He became sports editor of his junior high newspaper and editor of the paper at Galesburg High School. It was during college that Lawrence reconsidered his ambition to be a sports writer. He had become editor of the student newspaper at Knox College in Galesburg and, he notes, "involved in other issues." It was the 1963-64 school year and the civil rights movement had exploded onto the nation's radar screen. "There were kids in my class who had gone to the South on freedom marches," Lawrence recalls. Closer to home, he adds, "I attacked, editorially, discrimination on campus." He challenged recruitment policies of the admissions department, the practices of fraternities and the attitudes of others in the campus com- Illinois Issues May 1997 ¦ 21 munity. "I found it challenging and fulfilling to write about social issues." Those convictions took root around the Sunday night dinner table at the Lawrence household. "My dad worked he owned his own store 16 hours a day, six days a week. But that one night a week we'd all sit around the dinner table. Dad and Mom were not ones to lecture, but you could not sit at that dinner table without knowing what was expected. Dad was involved very strongly in the Human Relations Commission in Galesburg. They just made it clear that discrimination was ugly and should not be tolerated. We had a responsibility to go beyond family. There was also a responsibility to the community to make it a better place." His first job out of college, at the Register-Mail, cemented his devotion to public affairs. "I was on a beat where I really got interested in the dynamics of government and politics. It was the courthouse beat, and that's where I really caught the bug." He had the bug, but also something stronger: a vow to become a managing editor by the age of 30. In the early '70s, at the age of 29, he was named M-E of the Quad City Times. "And hated it," he says. "I consider that a period of not succeeding in a job the way I like to succeed," he says, choosing his words carefully. "But I probably learned more from that lack of success than from some of my successes in life. It taught me that you don't set goals by a title. I learned self-respect is very important." Then he happened to attend a meeting with Times editor Forrest Kilmer where Gov. Dan Walker was the featured speaker. As they were returning to the newsroom, Kilmer, given to impulse, blurted, "We ought to have a bureau in Springfield. Who should go?" Without hesitation, Lawrence answered: "Me." He had been to Springfield before in and out as a commuting correspondent for the Times in the late '60s, and he was "attracted to the state capital and to this arena." People who know Lawrence would never suspect he was on speaking terms with self-doubt, but he came to Springfield with a "lot of anxiety. "I had not been a reporter for several years, and I knew Kilmer would want me to produce right away. The first week I had three or four page one stories; that took the anxiety away." It was a remarkable time in the lore of the Springfield press corps. "The pressroom was extremely competitive," Lawrence remembers. Both AP and UPI then had three people staffing their bureaus. And, Lawrence notes, "There were some excellent investigative reporters Taylor Pensoneau was doing outstanding investigative work. During the '70s there was Lee Hughes at AP; Bob Hillman at the Sun-Times he was scrappy, always looking for a scoop; Roger Hedges at Gannett; Larry Green of the Daily News very, very scrappy; Carol Alexander in Decatur. There was a lot of that kind of reporting. It was really a challenge to compete." It was "the golden era of investigative reporting in the pressroom," says Pensoneau, who made a lasting reputation at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch before leaving journalism to lobby for the Illinois Coal Association. It was during those days that Pensoneau and Lawrence forged a friendship that

22 ¦ May 1997 Illinois Issues endures today, welded by similar professional temperaments, a love of sports and the conviction, says Pensoneau, that what they were doing mattered. "We felt we were governmental watchdogs." They went hunting for skulduggery and, says Pensoneau, "We tried hard to turn up wrongdoing wherever we could find it." Fortunately, with Dan Walker as governor and the usual quota of legislative misfits, investigative reporters didn't have far to look. "It was also a challenge to deal with the Walker Administration," says Lawrence. "The great thing about the Walker Administration for reporters was that every day he was trying to screw someone or they were trying to screw him. The Daley Democrats were trying to undermine Walker, or he them. It was really an exciting time. There was competition, fighting it was good copy. "I got the most mileage from a story I broke that some legislators were taping other legislators in connection with a bribery scandal. I also did a lot on the abuses of the state air fleet. I got to the point where I felt that if I failed as a government reporter, I could always find work as an aviation reporter." So successful did he become, that far from being displeased with his protege in Springfield, Forrest Kilmer called him back to Iowa "to nail down a story about the commander of the Iowa air guard abusing military aircraft. This guy had lost his wife, and he met a woman at a high school reunion and took military aircraft to Pensacola to court her. In Illinois, people would have just shrugged their shoulders, but not in Iowa." Though he enjoyed investigative reporting and had a definite flair for it, Lawrence also set himself apart from most other Statehouse reporters with another style of reporting, which burnished his image as not just a tough journalist but a serious one. "I actually cared about the policy issues," he says. "I enjoyed investigative reporting that was a great challenge. But I also enjoyed analyzing the issues exploring public policy issues and what went into the debate. I enjoy the game; it's fun to talk about. But the outcome always was more important to me than the game because what is done in Springfield affects people. The most important issues here affect human beings who are deeply impacted by government. Oftentimes, you get wrapped up in the game: who's winning, who's losing; who's popular, who's unpopular. I was always more concerned about the outcome because it affects children and people with special needs." After two years of Springfield reporting, Lawrence accepted an offer to return to the Quad City Times as editorial page editor, a decision governed largely by personal considerations and an impending second marriage. "I'd had a good run here," he says. "In retrospect, that might be the kind of job I would like today. That would appeal to me today and be more fulfilling than it was then. Then, I was in my mid-30s, and I missed the action. It was the wrong time." Then in January 1979, Lee Enterprises, a small newspaper chain that owned the Times and a few others scattered across the Midwest, purchased Lindsay-Schaub Newspapers, based in Decatur. Besides morning and evening papers in Decatur, Lindsay-Schaub owned the Southern Illi-

Illinois Issues May 199 7 ¦ 23 noisan in Carbondale. To Lawrence, the deal spelled opportunity. In October of that year. Lee opened a three-person bureau in the State-house pressroom, comprised of Lawrence as bureau chief; Mike Briggs, who succeeded Lawrence in the Times bureau; and myself, a refugee from Lindsay-Schaub. That launched, he says today, a period that he considers the most fulfilling of his career. "We did political and public affairs reporting the way it should be done," he says. "We focused on investigative stories, explaining issues and staying ahead for the next news story. That was when I was most comfortable with who I was." Under Lawrence's leadership and often through his reporting, the Lee bureau tried to make life uncomfortable for those in state government. Lawrence recalls a mammoth project by the Lee bureau that documented for the first time the practice that came to be called "pinstripe patronage," using no-bid state contracts to reward political donors and supporters, former cabinet officials and fallen legislators. "That is the kind of investigative journalism I enjoyed," he says. "But I also liked to get a tip at 8 o'clock in the morning and have it in the paper the next day. I didn't have a lot of patience." Ask Vince Toolen. Toolen was director of what was then called the Department of Administrative Services and apparently had expensive tastes in furniture. Working with information from the Better Government Association, Lawrence confronted Toolen with evidence of a $13,000 African mahogany desk purchased for the director's office. Briggs recalls that when Toolen exclaimed that Lawrence's pugnacious questioning brought on a certain paranoia, Lawrence answered: "You aren't paranoid, people really are out to get you." As the years passed, so did reporters in and out of the Lee Bureau. Briggs went to work for the Chicago Sun-Times, and now is press secretary for U.S. Sen. Carol Moseley-Braun. I left in 1985, and Lawrence the glue that held the bureau together departed in late 1986, ending 20-years of reporting and writing for the Lee newspapers. "The mission of the Lee bureau was beginning to fall apart," he says. "Some of the newspapers began to take the USA Today route," meaning a greater emphasis on soft news, short stories, glittery graphics, "and so there was not the market for the in-depth reporting that I liked to do." He took his Rolodex filled with sources and his hard-edged reputation down the hall of the pressroom to run the Sun-Times bureau. He stayed nine months. "Let's just say that what the Sun-Times wanted me to do is what I call 'wire-service' stories. At that stage of my career, I didn't want to do that kind of journalism. "I just burned out on journalism." Notes a former pressroom colleague: "Mike was done with journalism, and journalism was done with him. The kinds of stuff he was good at getting a tip that someone had taken a state car on a vacation to Florida the times had moved beyond running those kinds of things. That's not a negative comment on him; actually, it's too bad in many ways."

Still, Lawrence stunned the pressroom by announcing he had taken an offer to become press secretary to Secretary of State Jim Edgar. It was as if Michael Jordan had gone to play for the Knicks. Not long after Jim Edgar became secretary of state in 1981, Lawrence received a call from Tom Blount, editor of the Decatur Herald & Review. Edgar was planning to visit with the paper's editorial board and Blount was soliciting questions to ask him. Lawrence recommended some topics drunk driving, literacy and then asked, "You want to ask him about lights on the Capitol dome?" "No," Blount replied, "we can't see it from here." But Lawrence looked up every night, and he couldn't see it either the dome had been darkened since the energy crisis turned the lights out in the late '70s. Lawrence thought they should be turned back on, not just for the aesthetic beauty of the dome but for its symbolic importance: The Capitol was the people's building. As secretary of state, Jim Edgar was 24 ¦ May 1997 Illinois Issues in charge of the light switch. Mike Briggs: "Edgar's decision at Lawrence's strong and repeated urging to turn the lights back on the dome solidified his respect for Edgar as a man who does the right thing." That respect had been building, Lawrence recalls, since he dealt with Edgar as Gov. Jim Thompson's chief lobbyist in the legislature. When Thompson appointed Edgar secretary of state, the relationship blossomed over frequent lunches and, Lawrence recalls, "long philosophical discussions about government. He had a sincere commitment to good government. He has a good sense of humor and a strong knowledge of government and politics, and he is well-intentioned." So close would their relationship grow that in 1985 Edgar approached Lawrence about coming to work for him, but Lawrence was not ready to leave journalism. Two years later, he was ready. But with mixed emotions. "From the time I was 11 years old, my goal was to be the very best newspaper man I could be. I was not someone who aspired to go into government. I'm not anti-government, but it was hard because I envisioned myself writing press releases and I knew that as a reporter I threw most of those press releases in the wastebasket. I was also uncertain how I'd feel about being someone else's spokesperson instead of my own." The transition went as smoothly as perhaps is possible for someone whose adult life had been devoted to skewering politicians. "I was never as comfortable in the role of press secretary as in the role of journalist. I think I'm fundamentally a journalist. That said, the governor and I had a relationship that made the transition as easy as it could be. He's someone who has allowed me to be true to my principles. He has never asked me to lie for him. And he appreciates that I have strong convictions."

Strong enough that on those rare occasions in which they disagree (5 percent by Lawrence's reckoning) Lawrence has no hesitation in telling the governor bluntly what he thinks. "We've had some dandy arguments," he says. But despite such bold candor or more likely because of it Lawrence has enjoyed Edgar's full confidence and the authority that goes with it, a vital combination for the role he plays in the administration. "Many times if I encounter difficulty when I need to get information, I can be very difficult," Lawrence says. "I have had the governor's full backing, and that has been very important." Others say that, save for the First Lady, no one matches the influence Lawrence has with Edgar, nor the power that emanates from that relationship. "I have no doubt he is the most important person in the Edgar Administration," aside from the governor, says Tony Man, who succeeded Lawrence as chief of the Lee newspapers bureau. Adds Mike Belletire, who served with Lawrence on the governor's staff before becoming administrator of the Illinois Gaming Board: "Mike Lawrence never has had a problem telling Jim Edgar exactly what he thought. Except for the governor's wife, I don't think there is anyone quite as capable of doing that as Mike." Moreover, Belletire says, "People recognize that he has tremendous influence on the governor. He puts words to the governor's thoughts. Often, he is the first guy the governor turns to if he wants a second opinion. Mike has had a role that everyone recognizes and respects." Tony Man notes that "a lot of people in the administration are afraid of him. If he says something, no one doubts that it is coming from the governor." And Belletire points out that Lawrence's personality contributes to his mystique. He "harrumphs real well." It doesn't matter that underneath the bluster, Belletire says, "he's one of the easiest going guys around. He has a crusty sense about him, and sometimes people get afraid of that." Lawrence says that a lot of the skills and knowledge he gleaned as a reporter have served him well in his role in the governor's office. "I can cut to the heart of a matter. I have a good B.S. detector, so I know when I'm not being told the truth. I have the tenacity to probe for the truth. Before, I had the power of the press behind me; now, I have the power of the governor behind me." His role as press secretary, as Edgar's spokesman, scarcely begins to explain his station in the administration or his value to the governor. Lawrence is, first and foremost, the ethical compass of the administration and its chief enforcer. "He has been," says one observer who knows him well, "the conscience of the Edgar Administration." Adds Mike Belletire: "Mike is the guardian of the things that are best about Jim Edgar, the things that have impressed the people. Mike can say to the governor: "These are the things people think of Jim Edgar; they are what keep you who you are.'" They are things that Taylor Pensoneau calls "mid-American" values integrity, forthrightness, a sense of fair play, a seriousness of purpose, a belief in the political process, the con- Illinois Issues May 1997 ¦ 25 viction that if you work hard you'll get ahead that Lawrence learned around the Sunday dinner table in Galesburg, and Edgar harvested while growing up in Charleston. Whenever those values have been compromised, Lawrence has been quick to step in. "Hickman blames Lawrence for his problems," says one admirer, speaking of Robert Hickman, the governor's pal who was recently convicted of official misconduct in a land deal while executive director of the Illinois State Toll Highway Authority, a position to which Edgar appointed him. "It's funny how many people, when they fall out of kilter with the administration, blame Mike Lawrence for their downfall." Lawrence also was the impetus behind the investigation of the scandal involving the Public Aid contract of Management Services of Illinois, which has led to four indictments thus far. He says his action didn't win him friends within the administration. ' "There is a tendency on the part of public officials to let sleeping dogs lie," he says. "On the MSI thing I got the anonymous letter and moved on it right away and got the state police involved. There are people who are not happy with me, who thought we could have handled it internally. There are people within the administration who think I shouldn't have done that, but the governor has never indicated it was the wrong thing to do. It's not pleasant his name is in the headlines getting whacked around but he's been very supportive. "I feel protective of him." Too protective, in the eyes of some of his former colleagues. On the day in March 1996 that Al Salvi, an obscure state representative from his party's right wing, unexpectedly beat Lt. Gov. Bob Kustra in the Republican U.S. Senate primary, Gov. Edgar was briefing Republican legislative leaders on a dramatic new plan to reform education funding in Illinois. The plan, recommended by a commission headed by former University of Illinois President Stanley Ikenberry, called for a huge state income tax increase coupled with substantial property tax relief, all to be written into the state constitution by the vote of the people. When Rick Pearson, the chief Springfield correspondent for the Chicago Tribune, got wind of the meeting, he was ticked. He had spent the previous Friday chasing a "knock-down story" in which the Edgar Administration refuted claims by Salvi that the governor (and hence Kustra) was preparing a "tax bombshell" after the primary election. Two days later a Tribune story outlined the Edgar school funding plan under a giant headline: "Edgar readies tax bomb-shell." That morning Pearson was sitting in the pressbox in the Senate chamber when the phone rang, a rare occurrence. "Mike was on the line," Pearson remembers, "as angry as I can ever recall. He said I had destroyed any chance for school reform for every public school child in Illinois. I wasn't thinking of the story as something that destroyed anything." Lawrence's view is that the Tribune headline about a "tax bombshell" combined with Salvi's victory made GOP legislators so skittish about taxes in an election year that they refused even to give voters a say in the matter. "It made a grabbier headline," he says. "It was a more readable story to write it the way it was written. But it was irresponsible." So he called Pear-son and told him so. Many folks in the press corps, in Springfield and in Chicago, have received such calls. Pearson has had his share. "It's not common" for Lawrence to call with a complaint, Pearson says, "but it's not unusual." Even so, Pearson praises Lawrence for being accessible to the press corps, with the added benefit that the press secretary is not simply the governor's mouthpiece but his confidant as well. Tony Man says he has not had many run-ins with Lawrence, and is glad about it. "If he believes something, he believes it tenaciously," a word Lawrence also uses. "I've been on the other side of arguments," Man says, "but you don't want to be on the other side of arguments with him. That's not to say he's always right or always wins, but he fights tenaciously for what he believes." Lawrence characterizes his relationship with his old colleagues as "professional. I'm sure they're not happy with me from time to time. But I'm not happy with them from time to time. And if I'm not happy, I call them up and tell them I'm unhappy." Man says he has the sense that Lawrence has been "disappointed" at the quality of the press corps, believing that reporters are too often lazy or simply want the quick, sexy story rather than spend time investigating complex issues like school funding. Lawrence uses the same word. "Most journalists I deal with try to do a good job," he says. "And in some ways reporters today are more professional than when I broke in in the mid-'60s. They're not as cozy with lobbyists or public officials; they use tape recorders so they get quotes right, at least most of the time." He says Pearson has written responsible stories and "overall" the Trib is responsible. "But I will say that I've been disappointed with the coverage of politics and government. "There is a tendency to write far more about the game than about public policy issues and the potential consequences." Much of that tendency, he says, comes from newsroom editors. "But it's also easier to write from a horserace standpoint than about political issues. Many issues they deal with are complicated it's hard to do research, hard to write about issues in an interesting way." Instead, newspaper readers and TV viewers get stories with a common thread: "Is this Edgar vs. Daley? Edgar vs. Philip? Edgar vs. Madigan?" If journalism has changed around him, so has government. Or at least his view of it. "Yeah," he says, "it's changed a lot." He notes that he grew up in a household of "New Deal Democrats" during the '60s "when there was a definite need for government to get involved, primarily through civil rights laws. 1 grew up with a sense that government was not only a catalyst for solving problems, but also the primary problem solver. 26 ¦ May 1997 Illinois Issues

"Particularly since I've been in government, I've come to the belief that it needs to be more of a catalyst than the primary problem solver. When you're dealing/for example, with welfare reform, there was a time when I thought that government should set up programs day care and training and such. I've changed on that. The problems that beleaguer us most are not going to be solved unless you get communities, business, churches, neighbors involved. I have less faith in government to be the primary player in solving problems." But, then, listen to this. Asked what he believes his own influence on government has been, Lawrence says: "From my view, very little. My greatest satisfaction in being in government has been an ability on occasion to make something good happen for an individual." He says that early in Edgar's first term, he received a call from a woman who was having trouble getting a Medicaid prescription filled by a pharmacist. He called Phil Bradley, then director of Public Aid, and said, "It's unusual for a director to be involved in an individual case, but I want you involved. If she should get that medicine, I want her to get it. And I'd like a call back in an hour." Forty-five minutes later, Bradley called back: She had her medicine. "Those are the days," says Lawrence, "I feel it's pretty good that I'm in government." Soon he won't be. This summer, Lawrence will pack up his growl and head south, joining former U.S. Sen. Paul Simon in running a new think tank at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale and teaching journalism. But the legend of his bark will remain at the Statehouse, including the time, back in the '80s, when Mike Lawrence faced down the whole government of Illinois and got a guy named Johnny a job. Johnny blew it. But most people who want their government to be honest and decent and caring seem to agree that for the past 30 years it's been "pretty good" that Mike Lawrence, government watchdog, has been on the watch. Illinois Issues May 1997 ¦ 27 |

|

|