|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

Officials are demolishing some of Illinois' first public housing, erasing what we now believe is poor social policy. The bricks are falling because Congress is starting over too

Story by Jennifer Davis

Photographs by Judy Spencer

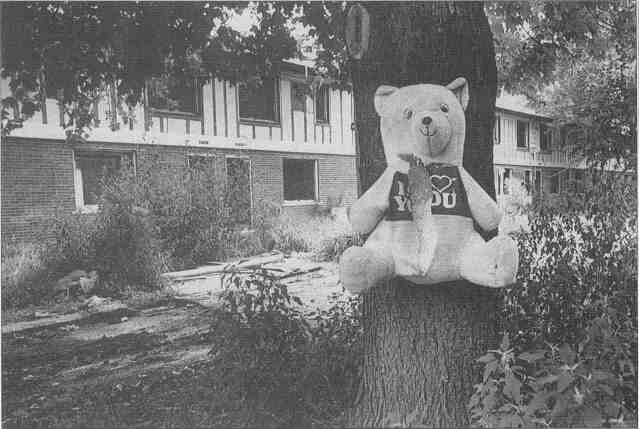

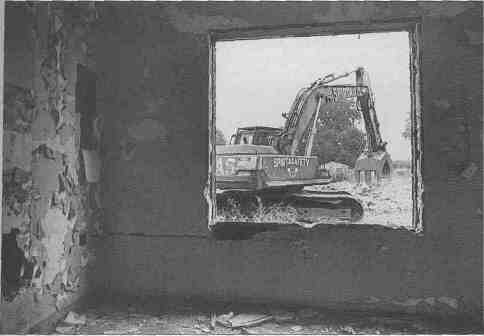

Broken bottles. A child's shoe. A ratty couch spilling its stuffing. It's Eugene Joiner's job to clear away this clutter so Springfield's John Hay Homes, the capital city's largest and most troubled public housing project, can start fresh. It's more than just tearing down some faded gray and blue siding and knocking down a few hundred brick walls. As Joiner, who spent a few teen years at John Hay, physically demolishes one of the first examples of public housing in Illinois, he's doing more than destroying his family's former home. He's erasing evidence of what we now believe is poor social policy. Once built with such promise, our modern-day cure for poverty and homelessness, the concentrated row- houses typical of John Hay are now thought to breed social ills. Still, the only reason these bricks are falling is because Congress is determined to tear down and start fresh too.

Joiner is knee-deep in rubble. Almost a thousand miles away in an air-conditioned office in our nation's capital, Linda Couch can sympathize. After all, she's up to her elbows in the paperwork equivalent of Joiner's mess. Couch tracks federal housing legislation for the National Low Income

20/ November 1997 Illinois Issues

Housing Coalition, which claims to be the only national organization devoted solely to ending America's affordable housing crisis. This has been a busy two years, what with renewed federal calls to reform our 60-year-old public housing law and the agency that administers it a fix-it job on par with John Hay's razing.

The U.S. House and Senate have both passed their own widely divergent bills: the House in May, the Senate in late September. Now they have until Congress adjourns this month to reach a compromise. It seems unlikely. After all, the House wants to repeal the 1937 Public Housing Act that guarantees affordable housing to the poor; the Senate flatly refuses. The House wants to authorize cities to take over housing authorities; the Senate, again, says no.

Last year also ended in congressional gridlock on the issue. Still, the move toward major change is undeniable. That is one thing Couch and others can agree on. What we have now isn't working. For one thing, about 15 million families nationwide need housing help and only 4.5 million get it. Those that do are many times living in crime-ridden slums, pockets of poverty isolated from jobs and a way out.

For the past two years, there have been repeated attempts to dismantle the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the federal agency responsible for some 3,400 public housing authorities nationwide. And other less sweeping reforms such as not requiring one-for-one replacement housing have been adopted. It's only a matter of time, says Springfield Housing Authority Executive Director Willis H. Logan, before we "drastically and dramatically change the way we approach housing."

|

Our nation's public housing

system is crumbling, literally, and in the minds of social reformers, who

once praised the small, modern apartments of such housing complexes as

Cabrini Green on Chicago's North Side. (Remember, they were considered

a step forward from such forbidding high-rise fortresses as St. Louis'

now demolished Pruitt-Igoe project.) It's time to take stock and rebuild.

The debate in Congress right now is akin to tinkering with tomorrow's blueprints.

Andrew Cuomo, secretary of HUD, is the first to admit the agency "has too many programs, too many failed attempts. ... We tried to house people. It was called Cabrini-Green and Pruitt-Igoe, and we don't want to try anymore." More aptly, we don't want to try that anymore. Congress responding to taxpayers' impatience with federal aid programs wants a new answer to the perennial problem: Where do we house the nation's poor? A portion of the answer, appropriately enough, is called "HOPE VI." Five years ago. Congress created the Urban Revitalization Demonstration program (HOPE VI) for the nation's most severely distressed public housing. Today, any public housing project can apply. This year the federal government will award $498.3 million in HOPE VI grants to public housing authorities in 27 cities nationwide. Instead of the recent stereotypical picture of public housing row- houses and brick towers, crowded together with patchy, littered dirt spaces squeezed between HOPE VI is pale stucco apartments in California with balconies and big windows. It's white farmhouses in Pennsylvania with front porches and steep roofs. It's "the last great chance we have," urges Cuomo. |

For Springfield, it's the opportunity to replace 600 nearly 60-year-old dilapidated apartments a pocket of drugs and crime on the city's East Side with a combination of apartments, duplexes and single-family homes. By not "piling people on top of people," as Willis Logan puts it, there's a chance to build a community.

Some green space and playgrounds, hopefully some stores that's the picture in his head. But that could change. Logan is philosophical. After all, he says, the community hasn't had its input yet, and there's still another several months before John Hay is even cleared away. There's also the matter of money. HUD has promised $20 million; what Logan envisions would cost more than twice that. But no matter whether the new buildings end up beige or blue, with siding or stucco, what Logan really wants is the John Hay of his past. Forty-some years ago, 10-year-old

Illinois Issues November 1997 / 21

"Billy-boy" Logan would run across 14th Street to play basketball with his buddies at John Hay. "It was the place to be," he recalls. At that time, the housing project was filled with families, most of them working. Indeed, public housing was first built for the working middle-class families of the Great Depression. It jump-started the housing construction industry and eased the nation's housing crisis in one fell swoop.

The John Hay Homes, the namesake of one of Abraham Lincoln's private secretaries, was one of the first housing projects built in Illinois. Peoria actually had the first, a $5 million project that began construction in June 1939. The John Hay Homes started going up the next summer. In the end, $2.8 million bought Springfield 599 public housing units, enough to house 2,500 people. The State Journal, Springfield's newspaper at the time, ran huge photos showing off the white walls and tiled floors and "the modern bathroom, kitchen with electric refrigeration and cooking appliances." They were beautiful, coveted apartments. Even years later, when Logan played hoops there with his friends, John Hay basically looked like every other surrounding neighborhood. Perhaps a little poorer.

Still, it was far from the ghetto he inherited in May when HUD began handing control of the housing authority back to the community. Those problems started, Logan believes, when Congress passed the 1970 Brook Amendment to the public housing law. "It was a good intention with bad results," he says.

Intended to help the very poor, the amendment pushed out low- and middle-income working families. Poverty became concentrated. Drugs and crime flourished. "A once bustling and vibrant community became a chaotic, despotic haven for negative activity," Logan says. But there are worse examples. Chicago for one. Indeed, Chicago's Cabrini-Green is a notorious nationwide example of what happens when you isolate the poor in a poorly managed housing authority. You get, ironically, what you set out to free people from a crime-ridden slum explains Howard Husock of the Reason Foundation, a California- based think tank. Husock is author of Repairing the ladder: Toward a new housing policy paradigm. Or, as Randy Boschulte, SHA's housing quality standards manager explains: "You put so many angry, broke, disenchanted people together, and you have the potential for a fireball."

On Chicago's South Side is a reminder of an even older housing policy. The State Street corridor, a four-mile stretch of high-rises that were considered a step forward when they were built, is the largest and most

| PICKING-UP

THE PIECES:

Community groups respond to the shortfall in housing One day they cut up the abandoned barracks from Rantoul's closed military base, strapped them to a flatbed truck and hauled them down Interstate 57 to Urbana's Grigg Street. Once there, Leonard Heumann and his group, the Homestead Housing Corp., went to work. Now they have 25 one-room apartments for the homeless. This month is their open house. This is just one example of what nonprofit community development groups like Heumann's are doing to meet housing needs statewide. It's a cause they've been increasingly pressured to take up. An estimated 15 million people nationwide qualify for housing assistance. Only 4.5 million get it. In Illinois, the exact need isn't known since communities do their own tracking, but, in general, Heumann would characterize it as great. "The federal government is basically telling us that religious groups and private industry have to do more," says Heumann, who is also professor of urban and regional planning at the University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign. "Churches, especially, are being expected to come in big time." And they are responding, says Tracy Auckamee of the Statewide Housing Action Coalition, which represents hundreds of religious groups and nonprofits like Heumann's in Illinois. In East St. Louis, for example, there's the East St. Louis Action Research project through the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Over the past seven years, that group has rehabbed homes and parks. It has even helped start up three independent community development organizations there. And Chicago, of course, has hundreds of ongoing housing projects. Still, groups that "once focused solely on building housing" are now offering job training, family support and even crime prevention, according to the authors of the recent Urban Institute study "Community Building Coming of Age." More so than federally run programs, community-based ones tend to involve residents. So far, so good. Indeed, there may only be one stumbling block, aside from the need for money to build new housing. And that is, according to the Community Development Research Center at New York's New School for Social Research, that community groups usually use grants or other one-time funds to pay for their projects. Often there's no money left over to keep up with maintenance and repairs, a problem that has plagued public housing. Howard Husock of the Reason Foundation, a California-based think tank, advises caution. "After all, when public housing was inaugurated, it too was initially well- received, before proving unsustainable in far too many instances." Jennifer Davis |

22 / November 1997 Illinois Issues

|

concentrated public housing

in the nation. In all, the Chicago Housing Authority is landlord to about

86,000 of that city's poorest people. And until recently, they admit, they

weren't doing the job very well. Even now, the federal government may force

demolition of 18,000 of CHA's worst apartments over the next five years.

About 40.000 people would need new homes.

"Nobody else has even half as many units at risk [of federally mandated demolition] as CHA," says Richard Monocchio, senior adviser to CHA executive director Joe Shuldiner. Indeed, there are rural housing authorities in Illinois with brand-new units sitting empty for lack of need. It's a long-running joke with Jane Lear, executive director of Logan County Housing in central Illinois. |

"I tell them all the time. 'Just stick 'em on a flatbed truck and move them here. I'll take them,'" says Lear, who is also president of the Illinois Association of Housing Authorities. Nevertheless, problems faced by the Logan County housing authority and the authority in Christian County, also in the central part of the state, are the opposite of Chicago's: small, few drugs or gangs, little crime.

Springfield fits somewhere in the middle in terms of size and problems.

While Springfield has drugs, gangs and crime, they're not as extensive as Chicago's. And also unlike the CHA, Springfield's Housing Authority was recently able to work its way off HUD's troubled list.

The SHA went on the list in 1991 because of low occupancy. More than half of its total 2,788 units were sitting empty, and it was taking the authority up to a year and a half to prepare a unit for the next tenant. But another reason, says Logan, is that "nobody wanted to live there." Springfield's public housing had deteriorated into cockroach- and crime-infested slums.

Last year, the federal government came in and took over, instituting a number of quick changes. Plans to tear down John Hay finally went forward. A new, stricter screening process for tenants was put in place. Maintenance and repairs were given top priority. Last month, things had improved enough that the feds packed up and went home. Today the SHA is under local control once again. And almost 80 percent of the authority's units are occupied.

"We're looking more at strengthening our programs in ways that reach beyond what we've done in the past," says Logan. "We're trying to think of how to give people new ways of thinking about themselves, new ways of thinking about their neighborhoods, new ways of thinking about their neighbors. We're not going to be able to change people's attitudes overnight, but we have to start somewhere."

Congress has to start somewhere too. We know now it's not good to isolate and concentrate the poor. So, it stands to reason, it must be better to recruit higher-paid working families to public housing. "We can't argue with the fact that mixed-income developments make sense," says Couch of the National Low Income Housing Coalition. "But who is going to house our poor? There's no place for millions of them as it is."

That Catch-22 is a big part of why Congress is moving so slowly toward reform. The goals of what we want public housing to be are still the same a decent place for the poor to live while they work toward independence but how we do that must be different. Now people move in and often stay. Critics say we're providing a handout, not a hand up, the original intent of public housing. Policy-makers have yet to agree on the future. All that's clear is our past mistakes. Much like the John Hay Homes.

Today, John Hay is a weed-choked wasteland of crumpled drainage pipe and splintered wood. Yesterday, it was a desperate, crime-ridden community. Sixty years ago, before John Hay, it was a 400-home slum. It's land with a past.

Yes, Logan smiles and nods. But he recalls the John Hay of his boyhood and he predicts:

"Out of the ashes of John Hay is going to come a beautiful new community"

Illinois Issues November 1997 /23